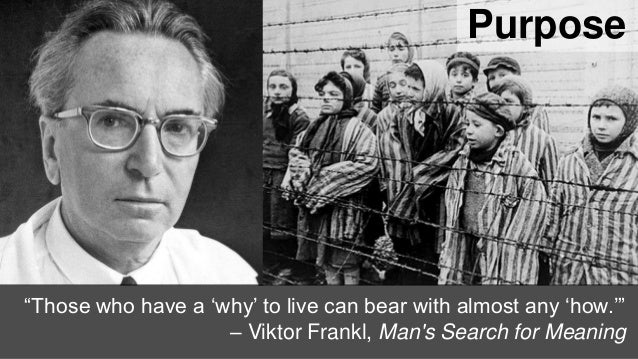

Viktor Frankl was put through some of the most horrific struggles a human being could imagine. But he never lost hope, and used his experiences to continue his work helping other people find meaning in their lives. Frankl’s story is one of strength, of hope, and of a man who made an impact on the world. Let’s dive into it…

Early Life

In 1905, Viktor Frankl was born the middle child of a Jewish family in Vienna. His parents were government employees, and the family was comfortable. Then World War I hit. Like so many other families of that time, the Frankls had to contend with bitter poverty. He and his siblings even had to go from farm to farm begging for food as the war progressed.

As a young child, Frankl showed interest and aptitude in the medical profession.At only three years old he wanted to be a doctor. Then, at four years old he had the realization every human has to go through – that one day, he would die. Still a toddler, Frankl’s life work had already started to take shape.

By the time he was in high school, Frankl was already studying psychology and philosophy. He even gave a speech called “On the Meaning of Life” in 1921, two years before his graduation. And when he had to write a final paper for graduation, what else would he write it on but the psychology of philosophical thought? By the time he turned twenty, he had already been in touch with Dr. Sigmund Freud. Frankl wrote Freud a letter and included a copy of one of his own papers in it. More impressively, the famous doctor then requested that Frankl allow him to publish one of the papers Frankl had written.

Later, recalling the incident, Frankl still sounded like he still couldn’t believe the incident even after decades of building up his own career.

“Can you imagine? Would a 16-year-old mind if Sigmund Freud asked to have a paper he wrote published?”

Nearly three years after that correspondence, Frankl was walking in a park in Vienna and encountered a man who looked familiar. Frankl went up to him, and asked if he was Sigmund Freud…he was. And when Frankl began to introduce himself…Freud recited Frankl’s address to him. Freud had been so impressed by Frankl that even as the years passed, he never forgot the letter he received from the young man.

Apart from psychology, Frankl also spent his high school years immersed in politics. He began his involvement with the Young Socialist Workers as a teen, and even rose to become President of the organization in 1924.

With a string of accomplishments in the field of psychology already achieved during his teen years, Frankl headed to the University of Vienna to formally study his chosen fields of neurology and psychiatry. Initially, he based his studies in the theories and ideas that Sigmund Freud had advanced, but over time he began moving more towards Alfred Adler’s ideas. Even after moving from Freud’s ideas, Frankl kept a bust of the preeminent Viennese psychoanalyst in his office.

Freud developed psychoanalysis, Adler added to that with the development of the inferiority complex, and Frankl become the third of these giants of psychology in Vienna as he developed a search for meaning called logotherapy as a key part of the study of the human psyche.

But before he became a world-renowned psychiatrist, Frankl was making a difference much closer to home. As a student he began actively putting into practice what he was learning and the theories he was developing. Moving beyond just academic interest in the human psyche, Frankl was able to literally save lives.

During his time as a medical student, Frankl noticed a disturbing trend among students in Austrian high schools. When grades were reported at the end of the school term, there was a spike in suicides. Frankl spearheaded an initiative to provide free counseling to students, with an emphasis on helping them at the end of the school term. Incredibly, the first year that Frankl’s program was implemented was also the first time in recent memory that there were no student suicides in Vienna.

With proven success in suicide prevention, Frankl moved on to become head of the Vienna Psychiatric Hospital’s female suicide prevention program. From 1933 to 1937, he worked with thousands of women who were in danger of committing suicide. Then, in 1937 he opened his own private practice.

But a year later, Frankl’s world was uprooted.

World War II

In 1938, Germany invaded Austria. Frankl was Jewish, and under the Nazi regime he was not permitted to treat Aryan patients. The Rothschild Hospital in Vienna was the only place where Jewish patients could be treated, and so Frankl was called upon to use his talents there as head of the neurological department.

While working at Rothschild, Frankl was also waiting to hear news that could lift him out of the terrifying situation that so many European Jews were in. He had applied for a visa to the United States, and just needed his lottery number to be called.

He was one of the lucky ones…his lottery number came up before Pearl Harbor and the United States’ entrance into the war. But Frankl’s decision to leave Austria wasn’t easy. The visa, it applied only to Frankl, and not to any other members of his family. His parents and siblings would be left behind in an ever-scarier environment, and Frankl knew their fate was likely to end in a concentration camp.

Frankl knew he had a choice to make, and he opted to depend on a higher power than himself to guide him in the right direction. When he came across a fragment of a stone in his parents house, he knew he had found the answer he was looking for. The stone wasn’t just any old stone – it was a piece of the Ten Commandments that had once stood in a local synagogue. Burned down by the Nazis, the Synagogue was reduced to rubble and Frankl’s father had picked up a piece of the stone for the family to have. And the piece he just happened to pick up? It depicted a portion of the commandment “Honor Thy Father and Mother.”

To Frankl, this meant his decision was clear. He would stay in Austria with his family and be right alongside them as they dealt with the horrors the Nazis brought upon them.

And Frankl well knew the horrors the Nazis were capable of. He and his wife Tilly were married in 1941, and the two of them wanted to have children. But Jewish couples were not allowed to have children. Frankl’s wife conceived, but she was not allowed to give birth. She was forced to have an abortion.

Then, in 1942, what Frankl had feared would happen came true. He, his wife, and his parents were arrested. They were initially sent to Theresienstadt, a camp in Czechoslovakia. There, Frankl did what he could to help others, running a clinic, helping new prisoners cope with the drastic shock of entry into the camp, and establishing a suicide watch.

Frankl, his wife, and his mother survived Theresienstadt, but his father did not. He died after only six months in the camp.

In 1944, Frankl was ordered to Auschwitz. His mother was also ordered to go, but his wife was not. But Tilly wasn’t going to be without her husband. She volunteered to be moved to Auschwitz.

The two ended up separated in the end, however.

After arriving at Auschwitz, Tilly was pushed onward to Bergen-Belsen, while Frankl and his mother were both kept at Auschwitz.

At first, they and fifteen hundred others were kept in a shed meant to hold only 1/6th that many people. The ground was bare, and the prisoners were forced to squat for days while they subsisted on only a small piece of bread. From here, the prisoners were directed into two lines…one to the gas chamber and one to years of labor and misery, but survival…at least initially.

Frankl’s mother was executed in the gas chambers, and Frankl himself barely escaped that fate.

Frankl was ordered to get into the left line, but defied the order and stepped into the other group. As he only discovered later, the left line was the line towards the gas chamber and certain death. He was one of the few to survive Auschwitz. 1.3 million people were sent through the gates of Auschwitz…and 1.1 million of them died. Those who didn’t die right away in the gas chamber suffered through deaths caused by starvation and disease, exhaustion from forced labor, and even medical experiments.

Though Auschwitz was the site of a huge number of atrocities, many others suffered in other camps throughout Europe. Frankl’s wife was one of those who met their fate in a different camp from her husband.

Tilly perished at the hands of the Nazis at the camp known as Bergen-Belsen, and Frankl did not learn she had died until the war ended and he was liberated in 1945.

Throughout his time suffering in the camps, not knowing Tilly’s fate, he was able to find meaning and a level of comfort in the knowledge of love. He thought of her throughout his ordeal in the concentration camps, and recognizing how that helped him he started to theorize about what love meant for human life. He later set out his thinking this way, in his famous work “Man’s Search for Meaning,”

“For the first time in my life I saw the truth as it is set into song by so many poets, proclaimed as the final wisdom by so many thinkers. The truth – that Love is the ultimate and highest goal to which man can aspire. Then I grasped the meaning of the greatest secret that human poetry and human thought and belief have to impart: The salvation of man is through love and in love.”

When he was in the concentration camps, Frankl had to distract himself from the reality of what he was going through. He saw death and suffering up close, he was forced into cattle cars, forced to march, contracted typhoid fever, and was separated from his most beloved family members. So what was one way he pushed himself forward to survive? As he explains,

“I repeatedly tried to distance myself from the misery that surrounded me by externalising it. I remember marching one morning from the camp to the work site, hardly able to bear the hunger, the cold, and pain of my frozen and festering feet, so swollen . . . My situation seemed bleak, even hopeless. Then I imagined that I stood at a lectern in a large, beautiful, warm and bright hall. I was about to give a lecture to an interested audience on “Psychotherapeutic Experiences in a Concentration Camp” (the actual title I later used . . .). In the imaginary lecture I reported the things I am now living through. Believe me, ladies and gentlemen, at that moment I could not dare to hope that some day it was to be my good fortune to actually give such a lecture.”

Frankl also made a point of finding a lesson in goodness and survival in the suffering he endured and the suffering he witnessed. These themes informed his life’s work.

“We who lived in concentration camps can remember the men who walked through the huts comforting others, giving away their last piece of bread. They may have been few in number, but they offer sufficient proof that everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms — to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

Post WWII

In April of 1945, Frankl had a welcome sight – American soldiers. They had come to liberate the concentration camps, meaning Frankl was once again a free man. He did not have family left, save for a sister who had escaped to Australia. He was essentially starting new in the world – but he had his ideas, his education, and his professional experience.

So he put his ideas into writing. In only nine days during the summer of 1945 Frankl dictated a full manuscript. The result was “Man’s Search for Meaning,” a description of what life was like in the concentration camps and the coinciding realizations Frankl had during his time as a prisoner about the need for meaning in human life and the role of suffering in the world. The book served as the basic outline for ‘logotherapy,’ the idea posited by Frankl that men are most driven by a search for meaning.

By 1946, he was fully back into his professional world, running the Vienna Polyclinic of Neurology. By 1948, he had earned a pHD in Philosophy. He began teaching at the University of Vienna, where he would remain as a professor until 1990.

After he was released from the concentration camp, Frankl also remarried. In 1947, he married Eleonore Schwint, and the two had a daughter together. As an adult, Frankl’s daughter followed in her famous father’s footsteps and became a child psychiatrist.

Though he was teaching at the University of Vienna, Frankl’s teachings soon began to make a worldwide impact. With Freud and Adler as his predecessors, Vienna had already established itself as a center of psychological and psychiatric study. Freud and Adler were the first and second schools of Viennese Psychotherapy, and Frankl’s ideas about man needing meaning in his life became the third.

By the mid 1950s Frankl was being invited to speak at universities around the world. He had also created the Austrian Medical Society for Psychotherapy, and headed up the organization. In 1955, the University of Vienna made him a full professor, and by 1961 he was serving as a visiting professor at Harvard and his ideas were being cemented in the minds of those studying psychotherapy in the United States. His academic career continued to grow, as he lectured at over 200 universities and was awarded an astonishing 29 honorary degrees.

Though Man’s Search For Meaning was by far his best known work, Frankl also wrote and published 39 other books during his lifetime. In 1970, he was honored by his peers when they created the “Viktor Frankl Insitute.”

Among his academic work, Frankl still worked with patients. One of his methods was to ask the most depressed patients he encountered a seemingly simple six word question…

”Why do you not commit suicide?”

From here, Frankl would discover what it was that the patient actually found joy in, what made their life worth living … in other words, what the meaning was in their life. Once that discovery was made, he could start helping them to improve their mental health and to move away from thoughts of suicide.

As the 20th century progressed, Frankl shared his ideas in media beyond print. He appeared on television to discuss his ideas, bringing them to an entirely new audience. In one of his most famous television appearances he expounded on his idea that in the search for life’s meaning one must have a balance of freedom and responsibility. During the discussion, he advocated for the United States to have a partner monument for the Statue of Liberty. The country should be bookended with a statue of responsibility on the West Coast, he argued.

“Freedom, however, is not the last word. Freedom is only part of the story and half of the truth. Freedom is but the negative aspect of the whole phenomenon whose positive aspect is responsibleness. In fact, freedom is in danger of degenerating into mere arbitrariness unless it is lived in terms of responsibleness. That is why I recommend that the Statue of Liberty on the East Coast be supplemented by a Statue of Responsibility on the West Coast”

Answering letters and doing interviews, Frankl continued to share his message and teach the world about his theories of psychoanalysis right up until his death in 1992. In one of his last interviews, Frankl made the poignant observation that even looking back decades later, he could still find value in his suffering at the concentration camps. As he saw it, the suffering gave him a valuable perspective on what real trouble is, making him more appreciative of the life he could live freely from 1946 onward.

“What I would have given then if I could have had no greater problem than I face today,” he said in 1995.

Legacy

When he was in the concentration camps, Viktor Frankl lived out the idea that he later imparted to the world in Man’s Search For Meaning:

“Everything can be taken from a man but one thing: the last of the human freedoms—to choose one’s attitude in any given set of circumstances, to choose one’s own way.”

While he was in the concentration camps, Viktor Frankl opted to think of his wife, to think of his profession, to theorize about how he could use his experience with suffering to impact others’ lives. He stole paper from the camp offices to jot down his ideas, and knew that he had two reasons to make it out alive – love, and a responsibility to help people find meaning and avoid what he called the “existential stress” of living without meaning.

From the time he was a student, Frankl was helping to save lives. Though he couldn’t save the lives of his closest family, he was able to persevere through unimaginable horrors and spend the next five decades making a positive impact on the world.

Viktor Frankl could have given up, he could have died, or he could have lived the rest of his life bitter from what he had gone through. No one would have blamed him. But instead, his life has touched millions, his book has been translated into 74 languages, and he’s impacted generations of new psychotherapists who will spend their lives helping people.

Viktor Frankl…a life lived with meaning, indeed.