Legend has it that on the 20th of June 1941, a team of Soviet archaeologists opened the tomb of a mighty Central Asian ruler, whose ruthlessness and skill in battle was second only to Genghis Khan. His tomb bore the inscription, “When I rise from the dead, the world shall tremble”.

When the archaeologists located the coffin, they read an even more ominous threat: “Whoever opens my tomb shall unleash an invader more terrible than I”.

Two days later, Hitler launched Operation Barbarossa against the USSR, the largest land invasion in history. The legend goes on that when the fearsome warlord was again sealed in his tomb, the Soviets won at Stalingrad.

The archaeology expedition actually took place, but I wouldn’t bet on the accuracy of the other details. But this story captures the fearsome reputation of today’s protagonist: Amir Timur the Lame, also known as Tamerlane.

A bandit and mercenary of Mongol origin, he rose through the ranks, becoming the most powerful ruler in the 14th Century Islamic world. Eventually, he conquered an Empire stretching from Delhi to the Mediterranean.

In the words of historian Beatrice Forbes Manz, Timur could boast “a stature bigger than life and a charisma bordering on the supernatural.”

A Boy Named Iron

Before we get into the birth and rise of today’s protagonist, let me give you some context. After the death of Genghis Khan, the Mongol empire was split between four of his descendants. His second son Chagatai inherited a vast territory in Central Asia, which became known as the Chaghadayid Khanate.

This polity included most of modern-day Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, parts of Mongolia and China’s Xinjiang province. This Khanate’s economy was based on nomadic herding and was less outwardly aggressive than its northern neighbour, the Golden Horde. This wasn’t out of the kindness of their hearts, but because of constant, internal strife and division.

Eventually the Chaghadayid Khanate fragmented into several entities, the largest being the powerful Moghulistan in the east, and the less formidable Transoxiana in the west.

In this divided land, a boy was born in 1336 AD.

His birthplace was Kesh, modern-day Shahrisabz in Uzbekistan.

His father was called Taraqai, a minor nobleman of the nomadic Barlas tribe. These were a Sunni Muslim, Turkicized Mongol group, once allied to Chagatai. At birth he was called Timur, meaning ‘iron’: a name which carried an omen of strength, tenacity and conquest.

Timur and family never had a place to call home. Following nomadic habits, they roamed the steppes south of the capital Samarkand, looking for the best pastures for their livestock.

The young Timur soon grew tired of looking after grazing animals. His parents were not clan leaders, but the Barlas society allowed upward mobility for tough youngsters who were handy with a composite bow, especially if shot from horseback.

Timur displayed a clear talent for violence and action, a talent which he put to fruition by stealing horses and sheep from neighbouring clans. Soon, he added banditry to cattle-rustling in his CV, and built a following of like-minded young warriors.

At the age of 21, in 1357, Timur trained his gang into a mercenary outfit, and entered the service of Tughluq Temur, the Khan of nearby Kashgar.

Shortly afterwards, the ruler of Transoxiana, Amir Kazgan died. Tughluq took the opportunity to invade, and in 1361 he conquered Samarkand. The young Timur must have played an important role in the conquest, as he was appointed chief advisor to Tughluq’s son, Ilyas Khoja.

From shepherd to bandit to minister, aged only 25.

Not bad, but not enough.

Timur was not happy to play second fiddle to Ilyas Khoja, so he forged an alliance with the ruler of Balkh, modern-day Afghanistan, the Amir, or Prince, Husayn. The friendship was consolidated when Timur married Husayn’s sister.

The two ‘bros’ kicked off a rebellion against Tughluq and Ilyas, which did not go as planned. The two fled to the region of Khorasan, south-western Afghanistan, where Timur resumed his mercenary activities.

In 1363, during a skirmish with enemy horsemen, an arrow pierced his right hand and knocked him off his horse.

As a result, he lost his little and ring fingers, and suffered a permanent injury to his right leg.

From then on, he developed a life-long limp. He also acquired the nickname that would make him immortal: ‘Timur i-Lenk’, or Timur the Lame – better known in the west as Tamerlane.

Rise of the Lame

At this stage, one may define Timur as an exiled upstart with a prominent physical disability.

This may have been a clear disadvantage. Especially in the territories spawned from the Mongol Empire, which valued physical prowess and nobility of blood. Only descendants from Genghis and their relatives could aspire to the title of Khan.

But Timur’s ambitions knew no boundaries.

In 1364 he spotted an opportunity to continue his climb.

Tughluq had died, and it was time to settle scores with his son Ilyas. Timur and Amir Husayn attacked Transoxania, conquering the entire region by 1366. As it happened before, Timur was the power in the shadows, while Husayn had assumed titular power as Khan, establishing a new capital city in Balkh.

But the relationship between the two brothers-in-law started to sour.

The Khan had grown arrogant, imposing a despotic rule and amassing the wealth of his subjects. According to some sources, he may have even kidnapped one of Timur’s sisters to join his harem! That’s a big no-no, of course. If you fancy your best friend’s sister, you better marry her.

But more realistically, the last straw was when Husayn refused to pay his soldiers’ wages.

In the spring of 1370, Timur started to plot, building alliances with other military leaders. Soon, he commanded a formidable army and went on the attack. Husayn’s forces were beaten time and again, until Timur besieged Balkh.

Husayn’s loyalists fought desperately, trying two sorties, which inflicted heavy casualties on their enemies. But Timur pressed on, and a defeated Husayn sought refuge in the mosque of Balkh, offering all his riches in exchange for his life.

According to contemporary sources, Timur shed some tears at the sight of his old friend begging for mercy. But his allies bayed for revenge and killed the Khan in cold blood. It seems, then, that Timur’s tears dried up very quickly as he collected an imposing war booty and married four of Husayn’s widows! One of them was Saray Mulk Khanum, a descendant of Genghis Khan.

With this new-found legitimacy, Timur restored the capital in Samarkand and declared himself sovereign of the Chaghadayid Khanate, restorer of the Mongol empire. Still, he styled himself as ‘Amir, rather than ‘Khan’, honoring the Central Asian traditions.

But titles meant little to the pragmatic leader. He knew that true power rested on the saddles and bows of his unstoppable army, and he was ready to build an empire.

Towers of Skulls

For the following 10 years Timur fought endless campaigns, conquering areas corresponding to today’s southern Kazakhstan, western Uzbekistan and the Xinjiang province in China. He even joined the Golden Horde in their fight against the Russians, occupying Moscow. And then took on the Lithuanians at Poltava, Ukraine.

Many of these campaigns may have been dictated by the opportunity to pillage some sizable loot, but Timur was a capable long-term strategist: his end goal was to consolidate power along the Silk Road, the wealthiest commercial route linking Europe to the Far East. By controlling it, he would ensure a consistent income to fund his expeditions.

He appeared to achieve victory without much effort, but of course the military prowess of his armies did not happen by chance. Timur’s forces were a composite bunch, with soldiers joining from every corner of Central and East Asia. But the core, the elite, came from the steppes of Transoxiana.

These men made up an army some 140,000 strong, disciplined and staunchly loyal. Timur’s almost supernatural charisma ensured they would follow him everywhere.

They fought mainly on horseback and their weapon of choice was the composite bow, which they mastered from an early age. By their early teens, each nomadic horseman was able to shoot an arrow every five seconds, hitting targets at 60 meters’ distance.

These highly mobile units were complemented by well-trained infantry, specialized in siege warfare.

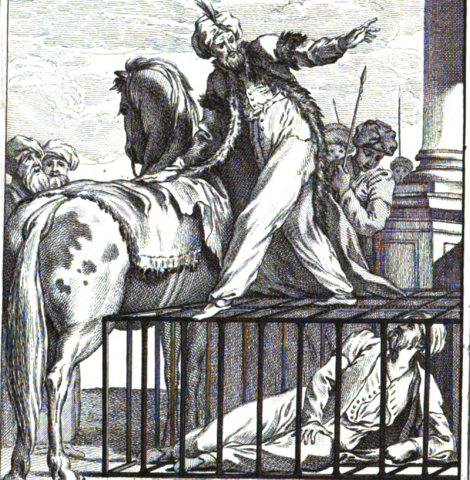

SPRY(1895) p388 – BAJAZET I. – A PRISONER BEFORE TAMERLANE, 28TH JULY 1402

When meeting an enemy in a pitched battle, Timur eschewed the traditional formation which included a center, wings, and a reserve.

Instead, he split his army into seven divisions: three at the front, three in support and a reserve to the rear. This allowed him to throw in fresh horses and riders when needed, wearing out the enemy defensive lines.

Furthermore, Amir realized the limitations of his army. He knew they were good at conquering, less so at holding new territories. Therefore, he concentrated occupation forces in rich agricultural lands, and was happy to let go of the less profitable steppes.

One such land full of riches was Persia, which the conqueror targeted in 1383.

The ruling Il-Khanid dynasty was extinct, and too many competitors vied to fill the power vacuum. Taking advantage of the civil strife, Timur invaded from the North, capturing Herat.

Its inhabitants suffered a horrific treatment, which was to serve as an example for other cities.

Timur’s army plundered all treasures, leveled ancient landmarks, and slaughtered many of the defenders.

Rumors of such ruthlessness spread across the country, and several cities, like Teheran, surrendered without a fight. Others, like Isfahan, fought back – only to regret it.

Timur ordered a massacre of Isfahan’s citizens, and their skulls were piled up in morbid towers, several meters high. By 1385, all of Eastern Persia had fallen. The land was depleted of its riches, as well as of its more talented inhabitants.

The Amir deported artists, architects, intellectuals and artisans to Samarkand, where they would contribute to the building of an imperial capital. In Timur’s vision, the city was to be the beating heart of the Islamic world, as well as the cultural hub of Central Asia.

Samarkand was to become a tangible testament to Timur’s ambition to be recognised both as the defender of Islam and the restorer of Gengis Khan’s greatness.

And the track record of the Lame Prince was indeed worthy of his role model.

Between 1386 and 1394 he was unstoppable. Southern Iran, Iraq, Mesopotamia and the Caucasus all bent the knee. Timur’s campaign to control Azerbaijan was conducted alongside Tokhtamysh, Khan of the Golden Horde. The two allies, though, soon dissented over who should control the Silk Road.

As we know by now, Timur was not above turning against old friends, and a new war was on!

Initially, Tokhtamysh had the upper hand, invading Transoxania and even besieging Samarkand. However, he was repulsed and Timur chased him back into the Russian steppes.

In 1391, the Golden Horde was defeated on the Kondurcha river, but they returned with a vengeance four years later. The two armies clashed again in April of 1395 over the Terek river, Northern Caucasus.

This time, many of Tokhtamysh’ Generals defected to the other side, and Timur’s victory was decisive.

During this campaign, the unstoppable conqueror razed to the ground the cities of Sarai, Azov and Astrakhan. As his attention was diverted, Persia revolted against the Amir. But the revenge was swift and utterly brutal: more towers of skulls obscured the sun.

Battling the Elephants

In September of 1398, Timur set his sights on India. In his view, the Sultan of Delhi Mahmud Tughluq was too tolerant of his Hindu subjects. He amassed an army of 90,000 men and crossed the Indus river, attacking Delhi on December the 17th.

Mahmud put up a strong defence by deploying dozens of war elephants, covered in chain mail and topped by wooden towers. But Timur had a plan. He had the battlefield covered with spiked iron caltrops, which wounded and diverted the attacking beasts. Then, he unleashed a charge of riderless camels, each carrying a load of blazing hay.

The terrified elephants stampeded their own troops, sowing confusion and panic.

The wonderful city of Delhi soon became another wasteland of ruins.

The following year, Timur looked to the West, to settle accounts with the Ottoman Empire and the Mamluks Sultanate of Egypt, guilty of having seized Mongol lands in Anatolia, modern-day Turkey. The confrontation began with some serious trash talk.

Timur wrote to the Ottoman sultan, Bayezid: “Thy obedience to the Qur’an, in waging war against the infidels, is the sole consideration that prevents us from destroying thy country”.

Bayezid replied: “What are the arrows of the flying Tatar against the scimitars and battle-axes of my firm and invincible Janissaries?”

Well, let’s see, shall we?

The Timurid steamroller galloped westwards, storming Aleppo, Damascus and Baghdad in 1401. 20,000 of its citizens were slaughtered.

After setting camp for the winter, Timur reached Anatolia in the early summer of 1402.

He first laid siege to the town of Sivas, promising not to shed a drop of blood if the inhabitants surrendered. They did – and 3,000 of them were buried alive. Technically, Timur kept his promise. The next challenge was Bayezid’s main army of 85,000 men. The two forces squared off at Ankara, on the 28th of July.

Timur had managed to turn many Ottoman vassals to his side, outnumbering his foe almost two to one.

But Bayezid knew how to fight a defensive battle: he deployed his infantry along a stream, on hilly terrain. Thus protected, the infantry could raise a shield wall, shielding the cavalry units from Timur’s attacks.

Seeing the futility of the initial charges, Timur decided to wear out the opponents with a stratagem. He had a creek diverted, denying Ottoman horses and their riders from access to water. The demoralised horsemen were ultimately scattered by a charge of war elephants, which Timur had imported from Delhi.

The elite Janissaries, now without mounted support, were easy pickings for Timur’s heavy cavalry, attacking their flanks. But Bayezid inspired his surrounded men to fight on, until nightfall. He then attempted to break out of the encirclement, but was captured by the enemies.

The Sultan was brought back to Samarkand, where he suffered a humiliating captivity at the hands of Timur, who allegedly used him as a footstool.

The Last Expedition

The Ottomans had thus lost not only their leader, but 40,000 of their finest soldiers.

The power vacuum in the Ottoman empire resulted in a civil war, to the delight of Western European powers. Always wary of the Ottoman threat, the Kings of England, France and Castile sent messages to Timur, congratulating him on his victory.

The Castilians even sent an ambassador to Samarkand, Ruy González de Clavijo.

Clavijo gave a vivid account of Timur’s court and exotic grandiosity. He was especially impressed by the Amir’s 15 palaces, many of which could be disassembled and moved when necessary. He also described how the supposed defender of Islamic faith was a heavy drinker who organized lavish feasts every night.

When one guest showed up late at one of his parties, Timur punished him by piercing his nose like a pig.

After Clavijo departed, in November of 1404, the ageing Timur prepared for what would be his last expedition. This time, on the receiving end: Ming China.

The Amir had a bone to pick with the Mings since 1395, when their Emperor had sent a message describing himself as “lord of the realms of the face of the earth” and treating Timur as a subordinate. He retaliated by detaining the Emperor’s envoys. When more messengers came looking for them, they also ended up in jail.

Timur’s plan was to get rid of the arrogant Emperor and replace him with the Yuan dynasty, descendants of Kublai Khan.

The usually careful planner, this time committed a huge mistake. Good sense would dictate initiating military campaigns in the spring, to take advantage of the good weather and plentiful pastures for the war horses.

But Timur set off in December 1404, at the head of 200,000 troops. His astrologers had seen good omens in the stars, but the weather begged to disagree.

Frosty climate made the trek increasingly difficult for the army.

Whilst crossing the Syr Darya river, Uzbekistan, the once undefeated leader fell ill, possibly as a consequence of the cold.

The scourge of Central Asia probably had wished for a glorious death in battle.

But in February of 1405, aged 69, Timur died of natural causes.

During his decades of military successes, the Prince had failed to create a functioning Government structure. Power was almost always centered around him. With no trusted lieutenant to take his place and inspire the troops, the expedition melted away.

The 200,000 soldiers marched back to Samarkand. Timur’s body, embalmed in oils and laid in an ivory coffin was buried in a splendid mausoleum, the Gur-e-Amir.

Legacy

Six centuries later, the legacy of Timur-i-Leng is controversial to say the least.

Driven by ambition and skill, a disabled cattle-rustler and mercenary had defeated some of the most powerful nations in Asia and the Middle East, assembling a large Empire. His actions in Anatolia weakened the Ottomans long enough to allow for the Byzantine Empire to survive 50 more years. And his defeat of the Golden Horde allowed for the expansion of Russia, Lithuania and Poland.

But while in power, he focused mainly on destruction and conquest. Some estimates place his death toll at 17 million, about 5% of the global population at the time.

His inattention to political matters eventually left his empire at the mercy of foreign invaders: as his line of succession was not clear, his last surviving son and his grandsons fought each other for dominance, losing the western half of the Empire

Nonetheless, his Timurid dynasty survived for yet another century, whilst Samarkand flourished as a centre for the arts, literature and science. A later descendant, Babur took control of Kabul and later Delhi, founding the Mughal dynasty.

I will leave the last word to you.

Was Timur a great ruler whose actions and influence had a huge impact on the geo-politics of Eurasia?

Or maybe you agree with military historian David Nicolle, who argued: “Timur might have been a great soldier, but in purely historical terms he could be seen as the greatest bandit of all times.”

LINKS TO SOURCES

The Rise and Rule of Tamerlane, by Beatrice Forbes Manz: https://books.google.ch/books?id=1Nzh_9DZ5DYC&redir_esc=y

Tamerlane’s Career and Its Uses, by Beatrice Forbes Manz: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20078942

Short Biographies: https://www.historyanswers.co.uk/people-politics/tamerlanes-reign-of-terror/ https://www.britannica.com/biography/Timur

Military strategy: https://www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/amir-timur-paragon-of-medieval-statecraft-or-central-asian-psychopath/

Timurid Chronology: https://faculty.washington.edu/dwaugh/hist225/225chron/timurchr1.html

Facts about Timur: https://ukdhm.org/40-facts-about-tamerlane-timur-the-lame/

Timur’s Disability: https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-20538810

Timur’s conquest of Balkh in 1370 https://www.jstor.org/stable/25818023