When talking about successful pirates — something we’ve done quite a bit of on this channel — you may conjure images of some rugged, bearded, European bloke, a Captain in command of a handful of ships and a few hundred men. He may have stolen a few hundred thousand Spanish Dollars, and may exert control over a sea route between, I don’t know, Yucatan and Cuba.

Well done you. That’s not bad. Here is my slow hand clap to congratulate you … but I am afraid that’s not going to cut it.

That’s because arguably the most successful pirate in history was a Chinese Admiral, in charge of a vast fleet of hundreds of vessels, manned by 70,000 men at its peak.

This pirate had total control over a huge coastal area, humiliating the navies of at least three major powers.

And this pirate… was a she.

She was known as Cheng Shih, Ching Shih or Cheng I Sao. She was a Master of Diplomacy, of trade, and of naval strategy. She was the undisputed Pirate Queen of the South China Sea.

The Little Girl of Kwantung

I would love to give you some details about the birth and early life of today’s protagonist. But the truth is that her origins were so humble and obscure that we don’t even know her exact date and place of birth. Sometime around 1771, somewhere in Southern China.

We are not even certain about her real name! Official records and histories refer to her by two names, Cheng I Sao – Cheng’s wife, or Cheng Shih – Cheng’s widow.

So, we can only imagine that the unnamed little girl was born to a family of poor farmers or fishermen, somewhere along the coast of Kwantung province.

We can only presume that she fought her way through disease and starvation, fending off infant death and slowly reaching adulthood.

While she grows up, I will give you some historical context, which will prove key for our story.

In the late 18th Century, China was a united and powerful State, under the rule of Emperor Qianlong, succeeded by Jiaqing in 1796.

Both Emperors belonged to the stable and powerful Qing dynasty, and had succeeded in expanding China’s territories and riches.

However, they had both failed at modernising the Empire to keep up with a massive population spurt. To oversimplify: many farmers were left with too little arable land to sustain themselves, leading them to seek other profitable trades, and not necessarily on the right side of the law.

At the same time, the Chinese civil service did not expand in proportion to the population. Hence, local government duties fell into the hands of local leaders, whose allegiances were to their localities and families, rather than to the state.

This situation created the perfect set of conditions for the rise of local warlords and rebellious factions, such as the White Lotus. Struggling to maintain internal order, the Chinese military was significantly weakened and depleted of resources … leading to the emergence of even more regional warlords!

Among them, especially in the Southern province of Kwantung, one could find powerful pirate lords, infesting the waters of the South China Sea.

In the 1790s, the southern pirates were on the rise, thanks to rich patronage provided by Vietnam.

There, in 1792, the Nguyen brothers had led a successful bid for power: the Tay Son rebellion. The youngest brother had become Vietnamese Emperor Quang Trung, defeating the rival Le dynasty. After the rebellion, Quang Trung had lost most of its navy, so he took to hiring Chinese pirates as privateers.

A typical Chinese privateer could afford a fleet of several dozen junks, manned by hundreds of sailors. Among these disparate gangs, one emerged as the most powerful: the fleet commanded by Cheng I, a man of ambition who sought to unify and merge the major pirate fleets into one single, dominant force.

A Match Made in Naval Heaven

And now we can go back to our protagonist. By 1801, she was in her late teens, or early twenties.

As expected, widespread poverty had forced her into a disreputable trade: prostitution. She peddled her trade aboard one of several floating brothels in Canton. On these refined boats of pleasure, patrons could enjoy a meal and a concert, before moving onto … the main entertainment, if you like. Which, apparently, was made even more pleasurable by the gentle rocking and rolling of the vessels.

She was renowned as one of the most beautiful girls on the floating palaces, admired for her looks as well as her charming and intelligent personality.

These were qualities which did not go unnoticed to pirate Lord Cheng I.

According to some versions of the story, Cheng I was so smitten with the girl’s beauty, grace and intellect, that he courted her for weeks before proposing to her. According to other versions, the pirate lord was initially motivated by pure lust. He had the girl kidnapped and brought on board his ship, just to have her all to himself.

Whatever the origin story you prefer, the next chapter is agreed upon: the girl happily and willingly became Cheng I Sao – the wife of Cheng I — but on one condition. She was not going to be relegated to the shore, playing the role of the worried wife, waiting for the adventurous husband to come home.

Or even worse: she was not going to be relegated to the bedchamber!

Oh no, she wanted to take part in Cheng I’s strategic decisions, lead the fleet at his side, sharing both the risks and the rewards of piracy.

In a decision uncommon at that time and in that line of work, Cheng I accepted and made Mrs. Cheng privy to his ambitions: unifying the Southern Chinese pirates.

Before achieving their goal, the couple found time to enlarge their family, in a rather unconventional way.

Some time in 1801, Cheng I’s pirates had captured the 15-year-old son of a fisherman, Chang Pao. Cheng I personally introduced him to a life of piracy by taking him as his lover. No surprise here, as homosexual and bi-sexual relationships were common amongst sea-rovers of all ages and latitudes.

The boy showed promise, and the Chengs gave him command of a junk.

Cheng I even adopted the teenage captain! This was no ordinary father-son relationship, though. The adoption was just a legal ploy, to ensure inheritance rights for his protégé.

As Chang-Pao grew older, it appears that Mrs Cheng was also involved in the relationship, making it one of those affairs the French call a ménage á trois.

Now, add to the mix the fact that the Chengs were formally Chang-Pao’s parents … well, let’s say that if Dr Freud had been born some decades earlier, had relocated to China, and opened a floating clinic in Canton, he would have made a fortune.

But the happy family had other concerns in mind.

In July of 1802, an occasion to unify the Southern pirates finally materialized.

The Tay Son forces in Vietnam had been defeated, meaning the privateers had lost their primary employer. The Chengs seized the day and established their own leadership by reorganizing the directionless pirates north of the Sino-Vietnamese border in the Kwantung province.

They successfully organized a conglomerate of small gangs into six large fleets, under the Red, Black, White, Green, Blue and Yellow flags.

By 1804, the six fleets were in perfect running order.

The Red Fleet was the most powerful one, boasting 300 ships and 40,000 men. Altogether, the alliance forces numbered 400 vessels and 70,000 men.

This was not a gang of pirates anymore. It wasn’t even a crime syndicate. This was a Navy, capable of holding its own against any sovereign Nation.

Cheng might have appeared as the charismatic leader with the hands-on experience and piratical resume, but the true strategic genius behind the lacquered screen was Cheng I Sao.

She ensured that leadership of each fleet was in the hands of trusted subordinates. They had some limited degree of autonomy over the running of their fleet, but were tied by personal or familial obligations to Cheng I, ensuring ultimate loyalty.

Mr and Mrs Cheng’s fleet was so successful that within a year, the Imperial authorities were unable to cope with the pirate threat. The sea-rovers of Kwantung indirectly caused the downfall of the provincial commander-in-chief; they directly killed his leading military commander: General Huang, known as ‘The Old Tiger’.

The success, however glorious, was short-lived. The husband and wife team was doomed to fall apart soon afterward.

The Widow’s Law

In 1807 the undefeated Admiral Cheng died suddenly, probably in a storm off the coast of Vietnam. His wife would come to be known as Cheng Shih – Cheng’s Widow.

Tradition dictated that she retired to a chaste widowhood. A quiet life, maybe tending to yard birds in the garden, or drinking tea on the seashore. All this, while perhaps admiring from afar the spectacle of an Imperial ship being blown up by the cannon fire of a pirate junk.

But Cheng Shih’s wouldn’t hear any of this. Her ideal retirement was to never have one in the first place.

The crafty pirate queen moved immediately to establish her position as the new Admiral of the combined fleets.

First of all, she secured the support of her late husband’s two most powerful chieftains, Cheng An-Pang and Cheng Pao-yang.

Then, she appointed Chang Pao, her adopted son, as leader of the most powerful Red Fleet. And to cement their alliance, she had no qualms in entering an open, monogamous, sexual and romantic relationship with him.

So, yes, she married her adopted son!

With strategic and diplomatic skill, the Widow had managed to retain the services of the leaders of the multi-coloured fleets. They all agreed that by working together, they would be more effective. Perhaps most importantly, they agreed to work together under Cheng Shih and Chang Pao.

Cheng Shih’s next move was to further consolidate her power. She did so by establishing a strict code of rules and punishments to maintain discipline and an effective chain of command in her sprawling Armada.

Here are some of the laws of Widow Cheng:

Number one!

Orders should follow a strict, top-down chain of command.

If, as a lowly pirate, you disobeyed orders from a superior, or gave orders of your own … your head would be chopped off on the spot!

Number two!

Any raid or business transaction had to be vetted by Cheng Shih. Backed by the might of the Red Fleet, she controlled the activities of every single junk.

After a successful raid at sea, the loot was to be supervised by an accountant. Cheng Shih allowed for the crew to keep 20% of their booty, but the rest had to be accumulated into a public fund, the kung-hsiang.

And if you pilfered from the fund … guess what? Your head would be chopped off on the spot!

Number three!

Women captured during raids should suffer no harm – they were too profitable! Well, good-looking captives, at least. They were to be sold into prostitution or slavery. Not-so-good looking girls were lucky enough to be freed almost immediately.

But what if a pirate raped one of the female prisoners? … Head chopped off!

And if the pirate had consensual sex with the prisoner? … Both of their heads would roll on the deck!

There was a way out of this punishment: a pirate could choose to take a captive as his concubine or wife. But if he did so, he was obliged to remain faithful to her for life. If he didn’t … you guessed it!

Number four: don’t harm the villagers – at least not the allied ones!

Cheng Shih had organised a network of coastal villages as supply bases for her fleet. If you stole from those villagers, of course, your body would be severed from your head in a sweet, swift cutting motion.

Finally, if you deserted or went AWOL, your ears would be cut off, and you would be paraded in front of your sneering crew mates.

If these laws were not enough, Cheng Shih and Chang Pao devised another scheme to control their subordinates. The Kwantung pirates were very religious and always beseeched their gods before going out for an expedition. To facilitate their prayers, Chang Pao ordered for a magnificent temple to be built on one of his ships.

Before major actions, Chang Pao and his lieutenants met at the temple to pray, burn incense and confer with the priests, seeking divine approval for their plans. Miraculously, the gods seemed to always agree with Cheng Shih’s and Chang Pao’s battle plans.

Well, the ruse was quite easy to spot: the two Admirals simply met with the priests beforehand, exposed their strategies, and ensured they would get “divine backing” – with air quotes – during the public ceremonies.

Now, you may rule over 70,000 hardened men by the clever use of smoke and mirrors, and by the ruthless wielding of the stick … but you also need to dangle the carrot.

Cheng Shi knew this very well, and she realised that to keep her men rich, fed, and happy, the loot stolen at sea may not be enough.

A Monopoly of Violence

Cheng Shih followed a pattern common to many successful criminal organisations in history — that is, she branched out into a legitimate business enterprise. In her case, it was the salt trade, one of the most profitable in the Kwantung area.

Between 1807 and 1810, the Chinese government employed a total of 270 junks collecting salt from the salterns at Tien-pai and hauling it to Canton.

Cheng Shih had deployed two squadrons along the route: the first in Tien-pai itself, and the other on the fortress island of Nao-chou, one of her favourite hideouts. From there, the pirate junks relentlessly assaulted the Imperial salt ships, capturing both the vessels and their cargo.

Eventually, the Empire retained control over just four of their merchant ships!

Cheng Shih’s genius stroke was not to content herself with selling the stolen salt. She got into the business by forcing the captured crews to continue hauling salt on her terms, ceding large part of the profits!

The Widow’s Armada had established total, armed control over the trade routes in the South China Sea.

One could say that she had established a ‘monopoly of violence’ over the area. This is a term which was later coined to describe the activities of the Sicilian Mafia, decades later, but it fits perfectly.

It was a simple reality: the pirates were the only ones who could decide if somebody would be harmed or not.

Unable to seek protection from the battered Chinese Imperial Navy, merchants in the South China Sea found it less risky and less costly to simply pay protection money to Cheng Shih, buying themselves safe passage on those otherwise treacherous routes.

This practice was applied to all sorts of trade, not just salt, and by 1809, it extended to the coastal villages, especially those on the Pearl River delta.

As I said, protection money is something you normally associate with the Mafia. But Cheng Shih was no Don Fanucci. She had no time to stroll around small businesses, pocketing envelopes of cash. She had ambition and an entrepreneurial mind.

She had set up financial offices in every major town on the coast, especially Canton and Macau. There, her agents collected fees from fishermen and traders, selling them official documents exempting them from pirate attacks. The agents then reinvested the cash they collected into buying weapons and ammunition for the fleet.

It was indeed a vicious, nautical empire – but one that ran like clockwork!

To maintain her monopoly of violence, Cheng Shih could even rely on a sophisticated intelligence network.

Initially farmers, fishermen, and other coast-dwellers were eager to cooperate with the pirate fleet, selling information on the whereabouts of enticing prey or enemy ships. Later on, Cheng Shih secured the cooperation of bandit gangs, secret societies, even corrupt state officials.

Ultimately, the supply chain and intelligence service created by Cheng Shih fed into the real muscle behind her power: the military prowess of her fleet.

She organised the larger fleets into powerful squadrons, which attacked in cohesive formations, resembling floating fortresses made of heavily armed junks.

Chang Pao’s personal squadron, for example, consisted of 36 vessels, manned by 1,422 men, operating more than 200 cannons.

The Imperial Navy was no match for such a force, and there are accounts of admirals in Kwantung sabotaging their own ships to avoid a confrontation with Cheng Shih.

The Emperor tried to deploy forces from other provinces, but to no avail. In 1808, for example, the military commander-in-chief of Chekiang province was dispatched to Kwantung in an effort to protect Canton with 135 ships and deal with the pirates once and for all.

It didn’t work. The Chekiang General was killed in battle, and within six months, the Red Fleet had destroyed 63 of the Imperial junks.

With little opposition at sea, Cheng Shih moved to attack coastal forts and garrisons. Her favourite tactic was to engage the positions from afar, by having one of her large squadrons deliver a devastating barrage of cannon fire. While the garrisons’ artillery was on the defensive, they failed to notice smaller junks carrying a landing party.

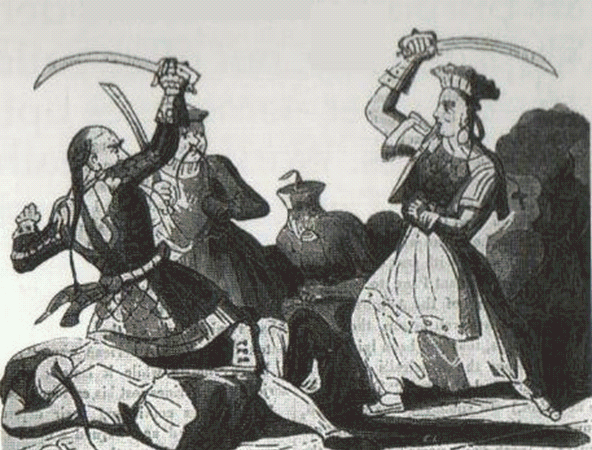

The amphibious force then stormed the walls, engaging the worn-down defenders in close quarters. This is where the pirates excelled, skilfully wielding their daos and jians. There are no confirmed accounts of Cheng Shih taking part in the fighting, but it is realistic to expect that she did not. As the overall leader, her strategic skills were too valuable for her to risk death in a skirmish.

There are, however, several accounts of pirate wives fighting fiercely alongside the first lines. A description of one of the few pirates’ defeats, at Lao Wan Shan, mentions a pirate wife who killed or wounded several soldiers, armed with a cutlass in each hand.

Formidable women also fought on the other side. An account of a battle between Chang Pao and a village militia features a formidable lady kicking pirate booty, side by side next to her martial arts master husband, Wei Tang Chow.

Overall, despite fierce resistance and the odd defeat, nobody in Kwantung proved to be a match for the fleet of many colours. With few domestic enemies left to prey on, Cheng Shih started looking outwards.

The Conflict Expands

Shih’s fleet escalated the attacks against ships belonging to foreign powers, including Siam, Portugal, the United States, and the East India Company.

In a matter of days, in September of 1809, Cheng Shih and Chang Pao attacked five American schooners in Macao, captured the brig belonging to the Portuguese governor in the Timor colony, and ransomed an entire tribute mission coming from Siam.

These were by no means the first attacks against Western shipping. In fact, attacks by the Chengs had been a nuisance to the British East India Company and Portugal for more than a decade. Their navies had offered to help in the fight against piracy, but the Imperial court had always refused, mainly out of national pride.

Finally, in that very same September of 1809, the Emperor agreed to negotiate with the Westerners. The Chinese Navy secured help from six Portuguese men-of-war, as well as from an East India Company ship, armed with 20 cannons.

Gradually, more and more Western vessels entered the fray, adding pressure onto Cheng Shih’s fleet, which gradually fell into numerical and technological disadvantage.

The crafty widow Cheng and her husband even tried to get the Portuguese to switch sides … on the 26th of December, the cheeky Chang Pao sent a letter to the commander of the Portuguese fleet at Macao, asking for three or four of their Men-of-war.

Chang Pao reassured that he was destined to topple the Emperor very soon! After the victory, he would have gifted two or three provinces to the Portuguese Admiral!

The pirate lord did not succeed in his negotiations, which was bad news for Shih. By early 1810, Cheng Shih’s fleet was showing the first signs of implosion. Their new enemies contributed to this, for sure, but the main reason was internal dissent among the fleet lords.

Cheng Shih had a choice: continue to fight against basically half of the world, or complete the transition to legitimate activities?

The risk was to see her Naval Empire crumble to pieces, her loyal sailors and soldiers dragged into chains or blown to pieces.

The other option was to seize an opportunity for negotiation, and see her men off to a wealthy career before it was too late.

She chose the latter option. While she was still in a position of strength, the Widow offered the Chinese Empire a tempting deal.

The Widow’s Proposal

On February 21, 1810, Cheng Shih and Chang Pao met with Pai-Ling, the Governor General of the Liang-Kuang territory – which encompassed Kwantung – and with Miguel Jose de Arriaga, a Portuguese official from the colony in Macao.

The widows’ proposal was simple: she would dismantle her fleet and surrender most of her ships and weapons.

In exchange, she demanded a total pardon for herself and all the pirates, as well as official appointments for Chang Pao and the other leaders.

The final condition was for her and Chang Pao to retain a ‘small’ force of 80 junks and 5,000 sailors.

These initial negotiations stalled when Pai-Ling refused that Chang Pao retained such a sizeable squadron.

No progress was made until April of 1810. On the 8th, Cheng Shih resisted her advisor’s concerns and bravely walked into Pai-Ling’s residence, escorted only by the wives and children of some of her Captains.

The stubborn widow would not have ‘no’ for an answer. If Pai-Ling wanted to get rid of the nightmare that was her fleet, he had to concede those 80 junks to Chang Pao! And she even raised her demands, asking for 40 extra junks for the salt trade!

Pai-Ling yielded.

Two days later, he met with Cheng Shih and her Staff at a pagoda in Macao, where they signed the final deal: immunity for all; 120 junks to Chang pao; and official appointments in the military and civilian administration for the subordinate leaders.

Chang Pao himself received a commission as Lieutenant-Colonel in the Imperial Army, receiving a promotion to Colonel soon after. Cheng Shih was now considered to be the respectable wife of a young, rising star within the military, and as such, she would be addressed with the honorific title of ming-sao.

Twelve years later, in 1822, Chang Pao died — perhaps during a storm, like his adopted father.

After having enjoyed more than a decade of quiet life at the expenses of the State, our twice-widowed protagonist settled back in Canton with the two children she had from Chang Pao.

Her last years of life were largely calm and prosperous. The once Pirate Queen invested in the salt trade and opened gambling establishments in Canton and Macao. Ironically, the one in Canton also doubled as a brothel.

From her position of wealth, she observed how the power of the Chinese Empire steadily declined in the 19th Century, bullied by Western Powers. It appears that around 1839, at the onset of the First Opium War against the British, she may have been consulted by the Kwantung governor on matters of naval strategy.

By the second year of war, in 1840, the woman known as the Widow Cheng had died peacefully in her sleep.

At the height of her career, Cheng Shih was a pirate queen who oversaw gambling and prostitution. She was, in every sense of the word, a crime boss.

But it is impossible not to admire how she reversed traditional gender roles and broke through a traditionally restricted female social mobility. She built her own career, her own ladder to success — first by acting as the power behind Cheng I, then by stepping into the power vacuum and assuming command. And then finally, by negotiating a masterpiece of a deal which ensured a quiet, gilded life for her and her cohorts.

The last word is with you: Cheng Shih – master criminal or role model?

LINKS

Historical Context

http://afe.easia.columbia.edu/timelines/china_modern_timeline.htm

https://www.chinahighlights.com/travelguide/china-history/the-qing-dynasty.htm

https://www.scribd.com/book/187370144

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Tay-Son-brothers#ref247908

Chinese pirates in general

https://www.jstor.org/stable/23881412?seq=1

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/323214499_Pirates_of_the_South_China_seas

https://thegsaljournal.com/2019/12/10/was-ching-shih-a-brutal-renegade-or-a-visionary-feminist/

Life of Cheng Shih

Maughan, Philip (1812). “An Account of the Ladrones Who Infested the Coast of China”. Further Statement of the Ladrones on the Coast of China.

https://www.atlasobscura.com/articles/the-chinese-female-pirate-who-commanded-80000-outlaws

https://books.google.com/books/about/The_History_of_Piracy.html?id=-x1jcFe-TCMC

https://daily.jstor.org/cheng-i-sao-female-pirate/

https://www.jstor.org/stable/41298765

https://books.google.com/books/about/Bandits_at_Sea.html?id=i6QUCgAAQBAJ

https://books.google.com/books/about/Pirates_Ports_and_Coasts_in_Asia.html?id=nEgb15isFZkC

https://books.google.com/books/about/Contemporary_Maritime_Piracy.html?id=pkNHFtJhG6UC

https://www.mentalfloss.com/article/58889/9-female-pirates-you-should-know