He was one of the 20th Century’s greatest icons. When Nelson Mandela walked free from prison in 1990, having served 27 years, he was already world-famous. The one-time leader of the armed wing of the African National Congress, he’d been sentenced to life imprisonment for standing up to South Africa’s racist Apartheid regime. Yet it was while in jail that Mandela had transformed from an inexperienced militant into the man who would bring democracy to his nation. First from his cell and then as a free man, he negotiated an end to white minority rule, the enfranchisement of the Black community, and managed to steer South Africa away from civil war. By the time he became president in 1994, his place in history was already assured.

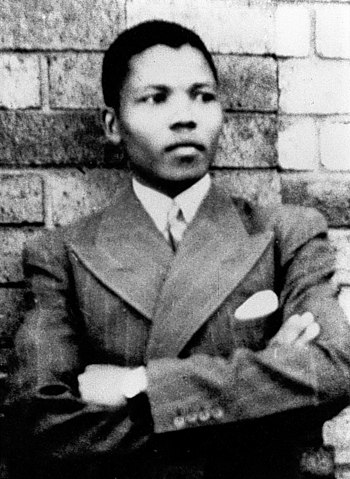

But while most of us know Mandela the statesman, how much do we know about Mandela the man? Born into royalty in 1918, Mandela entered a world which despised him simply for the color of his skin. First as a lawyer, then as a militant, Mandela fought to change this world… a battle which would see him humiliated and incarcerated, but never beaten.

The Beloved Country

From the moment he was born, on July 18, 1918, Nelson Mandela’s parents knew their boy was destined to shake things up. You can tell from the way they named him Rolihlahla, which translates as “troublemaker”.

But not even Chief Henry Mgadla Mandela could’ve predicted just how much trouble his boy would one day cause.

From the earliest age, Mandela’s life was full of contradictions.

On the one hand, he was a member of the royal house of the Thembu people. On the other, he didn’t exactly live in luxury. His family slept on straw mats, while his mother cooked over a simple hole in the floor.

Mandela himself grew up wearing his father’s old hand-me-downs. His first duty, aged five, was to work as a herder. Not exactly the sort of royal upbringing you see in old Disney movies. Still, Mandela did have advantages many other South Africans lacked.

From 1925, he was able to attend school – then still a luxury among the Black community – where his teacher bestowed on him the English name “Nelson”. When his father died at the end of the 1920s, he was adopted by the regent of the Thembu; allowing him to go and live in the “great place” of Mqhekezweni.

In later life, Mandela would say that it was at Mqhekezweni that he learned about leadership.

It was also where he learned to hide his pain.

When he turned 16, Mandela underwent the traditional rite of passage into manhood; a ceremony marked by circumcision with an assegai (or spear). Although he was prepared for it to hurt, Mandela was shocked at just how intense the agony was. He claimed it “felt as if fire was shooting through my veins.”

Yet, he was also aware that to show his pain would be weakness. So he raised his head and let out the cry of “’Ndiyindoda’!”

This ability to mask even the worst agony would become a hallmark of his life.

By the late 1930s, Mandela was continuing his education way beyond what most non-whites in South Africa could dream of. Aged 19, he enrolled in the nation’s only college for Black students.

From there, it was onto university, where he excelled at boxing and athletics, and began to dream of joining the civil service – the highest career a Black South African could then rise to.

Sadly, this dream wouldn’t last.

In 1940, Mandela took part in a student protest against the poor quality of canteen food. Rather than negotiate, the school summarily expelled him. Mandela’s guardian was furious, telling him he’d have to submit to an arranged marriage if he wasn’t going to study.

Instead, Mandela fled.

Stealing two cows from his guardian, he sold them, and used the proceeds to flee to Johannesburg. There, he settled into the township of Alexandra – a cramped, overcrowded slum for Blacks. At first, the young man found work as a night watchman, but he was soon fired and left destitute.

And there his tale might have ended, had he not met Walter Sisulu.

A real estate agent who was friends with one of Mandela’s cousins, Sisulu took the boy under his wing. He found a job for him at a law firm, where Mandela was able to complete a correspondence course. But, for our story today, the most important thing Mandela got from Sisulu was his friends.

Sisulu hung out with a whole lot of radicals, from Black African nationalists to white Communists.

The one thing they had in common was they wanted to tear down white minority rule.

It was a fight that was about to get a whole lot more urgent.

A Poison System

OK, it’s time for us to talk about the racist white elephant in the room: Apartheid. Although Apartheid officially began in 1948, less-official forms of the system had been around almost since South Africa’s 1910 formation.

The 1913 Land Act had begun the process by forcing Black Africans to live on reserves. In response, a small number of the Black elite had formed what would become the African National Congress (or ANC) to fight back.

Not that they’d had much luck.

In the years leading up to 1948, the separation had grown more and more entrenched, to the point that Black people could only enter non-Black areas for a specific reason. But, bad as things were, they were about to get worse.

On May 26, 1948, the white voting population handed a sweeping win to the Afrikaner National Party – whose campaign had used less racist dog whistles, and more racist bullhorns.

It was the National Party that named and implemented Apartheid (meaning “apartness” in Afrikaans); a system designed to not just separate Black from white, but white from every other race as well. Sex and marriage between whites and non-whites was outlawed; and the entire South African population sorted into the categories White, Black (or Bantu), Colored, and Asian.

Every urban area was then segregated along these lines, with only people from that category allowed to own a business, live in, or buy property in the area.

What job you could have, how you were educated, and even if you were allowed political representation all depended on the color of your skin.

And this was only the beginning.

In the mid-1950s, two new Land Acts handed 80 percent of all land in South Africa to the white minority – at a time when whites made up barely 20 percent of the population. Shortly after, the government created ten scattered African “homelands”, and began the forcible relocation of all non-urban Blacks into these Bantustans.

All told, around 3.5 million people were dumped into these places, where they plunged into extreme poverty.

Meanwhile, their confiscated land was sold onto whites at favorable rates. It was, in short, a criminal, racist system; one that become ever-more militarized and murderous as time went on.

It was also the system that compelled Nelson Mandela to fight.

By the time of the 1948 election, Mandela had already been a powerful member of the ANC’s Youth League for several years. During that time, he’d radicalized more and more, becoming attracted to an ideology of civil disobedience.

At first, this platform of Mandela’s had been ignored by the main ANC.

But then the National Party had come to power, and the idea of resistance had taken off, big time. In 1949, the ANC officially adopted Mandela’s Programme of Action, transforming itself into a militant organization. But while Mandela was already preparing to fight the Apartheid regime, he wasn’t yet ready to make alliances to do so.

In his early days, Mandela was a hardcore Africanist. Although the ANC wanted to work with local Indian and Communist movements, Mandela refused to get involved.

His efforts led to the ANC sitting out a Communist-organized strike in May of 1950.

Because of this, the Apartheid regime was able to crack down on the strikers much harder, unleashing a wave of brutality that shocked Mandela to his core.

In the aftermath of the carnage, Mandela met with his fellow ANC member, Oliver Tambo, who told him:

“Today it is our Communist Party, tomorrow it will be our trade unions, our Indian Congress, …. (then) our African National Congress.”

It was the beginning of a sea change in Mandela’s attitude.

No longer would he take a narrow, Africanist view of the struggle against Apartheid.

From now on, he’d take help from wherever he could get it.

Fight the Power

The further the ANC moved towards radical action, the higher up its ranks Mandela rose, eventually becoming Deputy President. A huge part of it came down to Mandela’s ability to organize people. He was a key player in a 1952 rally where attendees burned their Pass books – a kind of internal passport for non-whites under the regime.

He was also good at building bridges with other organizations, helping to create the multi-racial Congress Alliance against Apartheid.

And he took his activism into his personal life, too.

In 1952, Mandela and Oliver Tambo opened the country’s first Black law partnership.

Naturally, all this invited attention. In December of that year, Mandela was placed under a travel ban, forbidding him to leave Joburg. It was meant to stymie Mandela’s political organizing. But the wily young lawyer just turned to other means, helping organize the rainbow Congress of the People from afar.

Taking place just outside Joburg, Mandela could only watch from a distant rooftop as the Congress affirmed a Freedom Charter which read:

“South Africa belongs to all who live in it, black or white.”

It was a powerful, simple statement of truth.

It was also like waving a red flag at the racist Afrikaner bull.

Mandela was arrested alongside 155 other members of Congress Alliance and charged with treason.

His trial would drag on for the rest of the decade; all while the brutal realities of Apartheid only got more brutal. The pinnacle of this may have been the Sharpeville Massacre. In March 1960, white police officers unloaded submachine guns into a crowd of Black protestors, killing 69.

But rather than blame the racist cops, the government blamed the ANC and banned it outright.

Yet they still couldn’t stop its most-famous son from organizing.

Mandela was eventually acquitted at his treason trial and vanished underground, becoming a semi-legendary figure always one step ahead of the police. Although his law firm collapsed, he still had his contacts and his organizational skills.

But he had something else now, too.

A growing sense of anger.

The more Black bodies piled up at the hands of police; the more land was swiped from nonwhites, the more Mandela became convinced peaceful resistance was not the answer.

“A freedom fighter learns the hard way,” he later said, “that it is the oppressor who defines the nature of the struggle, and the oppressed is often left no recourse but to use methods that mirror those of the oppressor. At a certain point, one can only fight fire with fire.”

For Mandela, that “certain point” came in June, 1961.

Along with a close cell of loyalists, he formed Umkhonto we Sizwe (the Spear of the Nation).

They got hold of guns. Began preparing explosives. Yet even now, there was a sense that becoming a man of violence wasn’t Mandela’s destiny.

That summer, as he lay low on a friend’s farm in Rivonia, his second wife Winnie brought him a rifle.

Practicing his aim, Mandela shot a sparrow dead, only for his friend’s five-year old son to immediately start shouting at him “Why did you kill that bird? Its mother will be sad.”

According to Mandela:

“My mood immediately shifted from one of pride to shame. I felt that this small boy had far more humanity than I did.”

Yet Mandela had already chosen his path.

In December, 1961, Spear of the Nation set off its first bombs at government installations.

Although the attacks avoided casualties, they still put Mandela in the crosshairs of intelligence agencies across the globe. When he abandoned South Africa for eight months in 1962, it was with scary entities like the CIA watching him.

Which may explain what happened next.

That August, Nelson Mandela returned to South Africa.

Although in disguise, he was arrested by police who knew exactly who he was – long rumored to be due to a CIA tip-off. That day, August 5, 1962 was the end of Mandela’s time as a free man.

When he finally left jail again, 27 long years would’ve passed.

The Prisoner

Originally, Mandela wasn’t meant to spend anything like three decades behind bars. In 1962, all the police could prove was that he’d left the country illegally, so he received a mere five years. Unfortunately, half a year into this sentence the police raided a safe house and discovered a stack of bomb-making materials and illegal documents, all of which could be traced back to Mandela.

The result was the Rivonia Trial, named after the leafy suburb the safehouse was found in.

Starting in October of 1963, it returned Mandela to court alongside other ANC leaders.

The death penalty seemed such a foregone conclusion that Mandela used his last day in the dock to make a barnstorming, four hour speech, which ended with him declaring:

“During my lifetime I have dedicated myself to this struggle of the African people. I have fought against white domination, and I have fought against black domination. I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society in which all persons live together in harmony and with equal opportunities. It is an ideal which I hope to live for and to achieve. But if needs be, it is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

But die is exactly what Mandela didn’t do.

Instead, he was sentenced to life in prison on Robben Island.

It’s hard to comprehend nowadays just what a minor figure Mandela was when he went into prison, compared with who he was when he came out. Sure, he had a big following in South Africa. Sure, his travels in 1962 had seen him make connections with important people.

But he wasn’t internationally famous.

Were you to ask someone in mid-1960s America who Nelson Mandela was, they’d probably assume you had some weird speech impediment that prevented you from saying “Nelson Rockefeller”.

No, the reason Mandela became an icon isn’t because of his life before Robben Island, but because of his unjust imprisonment there. However, that recognition would take decades to accumulate. Decades in which Mandela lived a life of numbing tedium.

Imprisoned alongside other ANC members in Section B, Mandela was forced to do backbreaking labour in the midday heat – first in a lime quarry, then breaking boulders.

He was allowed to write only a single letter every six months, and receive two visits a year.

There was no compassionate leave. When both his mother and eldest son passed away in quick succession, Mandela was refused permission to attend their funerals. It was a life designed to make the world forget you. To cut you off from your family and networks.

But both Mandela’s allies and enemies conspired to keep his memory alive.

Wisely, the ANC used him as a symbol for all the political prisoners of Apartheid, giving the international community a name to latch onto.

But it was also thanks to the Apartheid government, who saw his growing reputation, and started making him offers – such as freedom in return for recognizing the controversial Black “homelands” they’d established.

Naturally, Mandela refused.

But it’s maybe too easy to portray the Mandela story as simply that of a saint, changing the world from inside his prison cell.

As admirable as Mandela’s courage and dignity were in this period, he was really just a symbol.

It was the people on the ground who were doing the tricky work of bringing down Apartheid.

Thanks to them, Mandela would be perfectly positioned when the time came to lead his country to democracy.

The Regime Unravels

As the 1970s dragged on, South Africa began acting more and more like the geopolitical equivalent of Cujo the rabid dog. There was the Soweto Uprising, when police fired tear gas and rubber bullets into a crowd of schoolchildren, injuring 4,000.

There was the repressive crackdown afterward, when 500 Black activists were detained and killed.

Then there was the new government formed under P.W. Botha in 1978.

Although it relaxed the rules on what had been called “petty Apartheid” – desegregating hotels, allowing interracial marriage – it also acted increasingly like a military dictatorship. Dissidents at home were imprisoned without charge. Others abroad were assassinated by the intelligence services.

By 1980, Botha’s government was engaged in dangerous military adventurism all over Africa; destabilizing its neighbors and meddling in civil wars.

They even developed their own nuclear arsenal, testing a bomb in 1979.

Yet none of this posturing could destroy the rot eating the regime alive. The rot known as Apartheid.

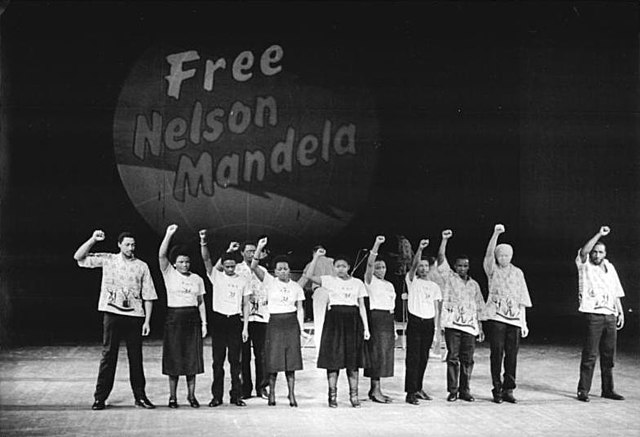

By 1982, an international campaign to free all political prisoners in the nation was gathering steam.

Known as Release Nelson Mandela, it called for sanctions and a boycott against South Africa until it embraced democracy. In response, Botha tried to unveil a new constitution that gave the racial categories of Asian and Colored more rights, while still keeping Black people oppressed.

But it didn’t work. Instead, community groups formed the United Democratic Front, which paralyzed the state with strikes and attacks on police. At the same time, the ANC began a new phase in its terror campaign – one not authorized by Mandela – that included the bombing of public buildings.

Come 1985, the economy was hurting under sanctions, and Botha had imposed a state of emergency.

Soldiers drove armoured trucks into Black townships; rounding up and torturing tens of thousands. Thousands more were murdered.

Yet this state repression was unsustainable, something even Botha realized.

In 1985, he made two separate offers to free Mandela, asking only that he renounced violence. Both times, Mandela refused. It’s here that we can see some of what made Nelson Mandela so great.

Although he’d now been in jail for over twenty years, Mandela refused to take the easy route out.

He wanted democracy in South Africa, damnit, not just his own freedom. And he was willing to wait and suffer until Botha was ready to deliver it.

But, in the end, it wouldn’t be Botha who cut the deal.

In 1986, the US followed the UN’s example, with Congress bringing in stinging sanctions against South Africa.

When this in turn was followed by an uproar after Mandela nearly died in prison of tuberculosis, even the National Party could see the writing was on the wall. On July 4, 1989, Botha came to personally see Mandela – now transferred to house arrest.

When Botha refused the prisoner’s call to free all those convicted of political crimes, he sealed his own fate.

A month later, his own party deposed him, bringing in the younger FW de Klerk.

De Klerk was more than capable of seeing which way the winds were blowing.

That December, the new president held his first meeting with Mandela. Although their relationship would be fraught – with Mandela never entirely convinced he wasn’t just dealing with another racist asshole – there was enough common ground between them to open negotiations.

But first, de Klerk would have to win the ANC’s trust.

On February 2, 1990, de Klerk made a speech freeing all political prisoners in South Africa.

It was so fast that even Mandela was taken aback. With almost zero time to prepare, he was suddenly released on February 11. On a day that would go down in history, camera crews gathered to film one of the world’s longest-serving political prisoners as he walked out of Victor Verster Prison and into legend.

Although his first words were a resounding “I greet you all in the name of peace, democracy and freedom for all,” Mandela later revealed just how confused he’d been at the attention. Part of this was to do with changes in technology. When he first saw a news crew point a boom mic at him, he thought it was an assassination attempt.

Yet, despite the overwhelming sensation of suddenly being both free and a celebrity, Mandela didn’t let it cloud his mind.

It was time for the real work to begin.

On the Knife Edge

In the multitude of parallel universes out there, there are a whole ton where South Africa in the early 1990s went the way of Yugoslavia. With Apartheid crumbling, huge swathes of the population were itching for civil war.

There were white supremacists who wanted to maintain their privilege. There were Black radicals who felt a violent reckoning was the only way forward.

But there were also regional leaders ready to seceed. Opportunists who saw violence as a way to accumulate money or power.

In short, the nation on the brink.

The only reason it didn’t fall into the abyss was due to Nelson Mandela.

Negotiations to end Apartheid began in 1990, but it was a long and painful process. Although Mandela was made leader of the ANC, he couldn’t stop the political violence gripping the country.

There were massacres. Assassinations.

Even as negotiations inched forwards, it kept looking like everything might fall apart. Like the only way out might be bloody conflict. Yet Mandela never gave up on a peaceful solution. Deep in his heart, Mandela sincerely believed a rainbow South Africa was the way forward, one that existed for all races.

Had he not been so convinced, Mandela may have never found the strength to push on with negotiations.

But Mandela persevered. And his perseverance paid off.

In September of 1993, the ANC and National Party agreed the date for South Africa’s first democractic election. For their efforts, Mandela and de Klerk won the Nobel Peace Prize. But it was touch and go until the very last second.

On April 27, 1994, the ANC won a staggering 62% of the vote in South Africa’s first post-Apartheid election.

And, just like that, Nelson Mandela became president of the nation that had tried to destroy him.

In his inauguration speech, Mandela pledged to build a “rainbow nation”. He made de Klerk his VP, creating a government of national unity. His biggest breakthrough, though, came in the immediate aftermath, when he succeeded in drawing white right-wing parties into negotiation.

After that, it was only extremists who continued to insist the new government was illegitimate.

The first few years of the Mandela presidency were filled with historic moments.

There was the establishment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, which allowed perpetrators of crimes to apply for amnesty in exchange for confessing. While not perfect, it has since been held up as a model for post-conflict societies: creating an impartial system that allowed families of the dead to discover the truth.

This included truths that were personally embarrassing for Mandela, as when it was revealed his ex-wife Winnie masterminded the abductions and murders of suspected informers. Another great moment was the unveiling of the new, democractic constitution in 1996, forever consigning white minority rule to the dustbin.

But the most-emotional moment likely came in 1995.

At the Rugby World Cup, Mandela openly supported his nation’s team, the Springboks; until only recently a team associated with Apartheid rule.

When he presented the trophy to the captain, it was a national moment of healing.

But, of course, Mandela’s presidency wasn’t just a litany of feelgood moments.

He badly misjudged the AIDs crisis, something he’d deeply regret in later life. He also cozied up to some super-shady regimes; openly embracing both Colonel Gaddafi and Robert Mugabe. By and large, though, when Mandela stepped down after a single term in 1999, it was with a sense of triumph.

Just nine years earlier, he’d walked out of prison and into a deeply-divided nation on the brink of civil war.

Now, he was stepping down as leader of a multi-racial democracy that had finally made peace with itself.

Of course, history isn’t a fairytale. South African presidents post-Mandela have struggled with corruption and cronyism. But the fact remains that Mandela himself was a model leader; a man who continued to do good even after the presidency by working in conflict mediation, and raising awareness of HIV.

Sadly, not even history’s greatest leaders can stay around forever.

In January, 2011, Mandela was checked into hospital, the beginning of a long illness that would eventually claim his life.

Although he clung on for nearly three years, there was nothing that could be done.

Nelson Mandela died on December 5, 2013, at the age of 95.

With his passing, the world lost a true hero of the 20th Century; one of the few great leaders who deserved his reputation. Today, over half a decade later, we live in a world that seems to be sliding ever-further into division. A world in which hatred is the new normal, and forgiveness a sign of weakness.

It’s a world in which we need the example of Nelson Mandela more urgently than ever.

Here was a man who suffered under his enemies in ways we can’t possibly imagine. A man who saw a racist regime destroy everything he held dear. And yet, when the time came, Mandela didn’t choose to hit back. Didn’t choose the easy path of violence.

No. Instead, he chose the much-harder path of understanding. Of reconciliation. Of healing.

It was a tough path to walk, one fraught with dangers. But, in the end, Mandela did it; showing his countrymen that division was not natural, that war wasn’t inevitable.

For setting this example, he remains one of the greatest leaders who ever lived.

Sources:

Detailed biography, South Africa History Online: https://www.sahistory.org.za/people/nelson-rolihlahla-mandela

Mandela Foundation bio: https://www.nelsonmandela.org/content/page/biography

Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/biography/Nelson-Mandela

Color Lines obituary: https://www.colorlines.com/articles/political-obituary-nelson-mandela

Detailed Guardian obituary: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/dec/05/nelson-mandela-obituary

Spiegel obituary: https://www.spiegel.de/international/world/obituary-nelson-mandela-dies-at-the-age-of-95-a-937581.html

History of Apartheid: https://www.britannica.com/topic/apartheid

History of Apartheid: https://www.history.com/topics/africa/apartheid

Congress of the People: https://www.sahistory.org.za/article/congress-people-kliptown-1955

Sharpeville Massacre: https://www.britannica.com/event/Sharpeville-massacre

South Africa history: https://www.britannica.com/place/South-Africa/The-unraveling-of-apartheid

Apartheid statistics: https://www.cjpmefoundation.org/blacks_under_apartheid_south_africa

Winnie Mandela crimes: https://www.sahistory.org.za/dated-event/winnie-mandela-found-guilty

Jacob Zuma corruption: https://uk.reuters.com/article/us-safrica-zuma/south-africa-corruption-inquiry-to-summon-zuma-to-appear-next-month-idUSKBN26U0XD