“Dear Boss,

Grand work the last job was. I gave the lady no time to squeal. How can they catch me now. I love my work and want to start again. You will soon hear of me with my funny little games…My knife’s so nice and sharp I want to get to work right away if I get a chance. Good Luck.

Yours truly,

Jack the Ripper”

Those were extracts from a letter that London’s Central News Agency received on September 27, 1888. It was then forwarded to Scotland Yard who were in the middle of investigating, perhaps, the most notorious killing spree of all time. Someone was attacking women in Whitechapel, murdering them and then cutting up their bodies in gruesome fashion. The killer went by many names – the Whitechapel Murderer, Leather Apron, Saucy Jacky, and, of course, Jack the Ripper.

He remains unidentified to this day so we will focus on his grim body of work – the murders, the suspects, the investigations. Few, if any other killers in history have inspired so many studies, books, and hypotheses courtesy of police officers, historians, writers, and crime buffs who are collectively known as ripperologists. Today we explore the life of Jack the Ripper.

The Autumn of Terror Begins – Mary Ann Nichols

In 1888, the Whitechapel parish in the East End of London was a place rife with crime. It was an overcrowded low-income area with terrible housing and working conditions. There was a brothel on every corner and a bar next to every brothel so the residents may indulge their vices and forget about their poverty-stricken lives. But even for such an area, nobody was prepared for what they were about to discover one early morning on August 31.

A man named Charles Cross was on his way to his job on Buck’s Row. On the way, he found a woman lying prone in the street, with her skirt raised above her waist. Cross and another man named Robert Paul approached her and touched her head and hands, unable to decide if she was dead or merely unconscious. The two concluded that they should pull down her skirt and that they would alert the first police officer they encountered but, otherwise, they had jobs to get to. The streets of Whitechapel were poorly lit and it was still night outside. In the darkness, even up-close, neither man noticed that the woman’s throat had been slit and her abdomen mutilated.

A police constable named John Neil came upon the body, followed closely by Constable Mizen who had been alerted by Cross. A third constable went to fetch the doctor. The physician pronounced the woman dead and concluded that she had been killed about half an hour prior. This meant that the killer was, likely, still in the area when Charles Cross walked by.

The victim was Mary Ann Nichols, a prostitute who also went by “Polly”. At first, her murder was linked to a few other killings which we will talk about a bit later. While some blamed a violent gang, the newspapers ran with the story of one deranged killer preying on these women.

In the weeks that followed, street gossip created the belief that the killer was a local Jewish man known as “Leather Apron.” Whitechapel had a large Jewish population so resentment against them was high. Of course, the newspapers were more than happy to fuel this sensationalism.

Whether it was due to frustration, incompetence, or outside pressure to do something, the police decided to arrest John Pizer in September. He was a Polish Jew who worked as a shoemaker and some said that he was sometimes called “Leather Apron.” He also had a prior conviction for a stabbing attack. This was all the police had against Pizer but, fortunately for him, he had a solid alibi that exculpated him. Pizer even won a libel case against a newspaper that declared him to be the killer.

The Second Murder – Annie Chapman

On September 8, the Whitechapel Murderer struck again when the body of Annie Chapman was found in the backyard of Danbury Street by an elderly resident. He flagged down some passing workmen who alerted the police.

Chapman’s throat had a deep cut and her body had been mutilated with multiple stab wounds, immediately suggesting a connection with the murder of Mary Nichols. She had been disemboweled and her intestines had been severed, lifted out of the body and placed on her shoulder. A later post-mortem examination revealed that the killer had removed and taken Chapman’s uterus.

Dr. George Bagster Phillips examined the wounds and ascertained that they were caused by a very sharp knife with a long, thin, and narrow blade. It could have been the surgical instrument that a doctor might use for a post-mortem. Phillips also said in his testimony that the murderer showed “indications of anatomical knowledge.” These conclusions gave birth to the idea that the killer might be someone with a medical background, a notion that is still pervasive today.

The murders caused a huge sensation in London and were discussed in every newspaper in the city. Meanwhile, the police had to contend with an unexpected problem that significantly impeded their already-plodding investigation. They had to look into hundreds of letters received from the public.

Broadly, these missives could be placed into two categories: letters from people offering suggestions or information on how to catch the culprit and letters alleged to be from the killer himself.

The police received upwards of 700 letters from the public. Hundreds were purportedly from the Whitechapel Murderer, either taunting or expressing remorse for his actions. You might imagine how this made it almost impossible for the police to ascertain which of the letters, if any, were useful or genuine.

That being said, there are a few which are believed by many investigators to have some merit. The first one we mentioned in the intro of the video. It was sent to the Central News Agency almost 20 days after the murder of Annie Chapman. It starts with the words “Dear Boss” and ends with the murderer giving himself a name. From now on, he is known as Jack the Ripper.

The Double Event – Catherine Eddowes and Elizabeth Stride

At first, the “Dear Boss” letter was dismissed as a hoax like all the others. However, one particular phrase garnered the interest of the police. When talking about his next job, Jack said that he will “clip the ladys ears off.” This became relevant when, just a few days later, the killer did just that. On September 30, two women fell victim to the Ripper: Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes.

First off was Elizabeth Stride, also known as “Long Liz”. She was last seen around midnight in the company of an unidentified man. She was killed soon after that and her body had already been discovered by 1 a.m. at Dutfield’s Yard on Berner Street.

Liz died from a long, six-inch gash in her neck, but had suffered no mutilations. Because of this, some are still reticent to count her as a Ripper victim, believing that she could have been the target of an unrelated attack. However, others consider that there are enough similarities such as location and killing method to group her with the other women. They believe that Jack did not cut up her body because he was either rushing to kill again or, perhaps, because he was interrupted.

This is where a Hungarian Jew named Israel Schwartz came in with an interesting story to share which, if true, meant that he might have been the interrupter.

Schwartz told police that he saw a man assault a woman on Berner Street at around 12:45 a.m. that night. Believing he was witnessing a domestic spat between husband and wife, he wanted nothing to do with it and crossed the street to avoid them. He later identified Long Liz as the woman he saw that night. His cowardice was subsequently mocked in newspapers which labelled Schwartz a “hen-hearted creature.”

There are two peculiar details about his story. Firstly, Schwartz claimed that there was a second man in the vicinity smoking a pipe. Secondly, the witness said that the attacker saw him and shouted something at him. Schwartz believed the word was “Lipski”, an anti-semitic slur which referenced Israel Lipski, a Jewish man hanged for murder the year before. We don’t know how serious police took Schwartz’s account, but they did not call on him to testify at the inquest. Their records do indicate that they tracked down and eliminated the second man as a suspect.

Meanwhile, within walking distance of Berner Street, Jack had found himself another victim named Catherine “Kate” Eddowes.

After midnight, Kate was walking the streets of London after being released from jail for drunken behavior. She ended up in Mitre Square and was last seen alive at around 1:30 a.m. in the company of a man by three Jewish gentlemen leaving a club on Duke Street. One of those three, Joseph Lawende, got a decent look at the couple and described them, although he mainly remembered their clothes and not their features.

Eddowes body was discovered soon after by a constable walking his beat. Her neck had been cut and her body suffered gruesome mutilations, more extensive than any of the previous victims. Her face was disfigured, her intestines were removed and placed on her shoulder again, and the killer had removed her left kidney and part of her uterus. Jack had also cut off Kate’s right ear which is what convinced authorities that the “Dear Boss” letter was the genuine article.

More Letters Arrive

Speaking of letters, the next day the Central News Agency received a postcard. The text said:

“I was not codding dear old Boss when I gave you the tip, you’ll hear about Saucy Jacky’s work tomorrow double event this time number one squealed a bit couldn’t finish straight off. Had not time to get ears off for police thanks for keeping last letter back till I got to work again.

Jack the Ripper”

The details and the handwriting suggested to police not only that the postcard was real, but that it was written by the same person as the “Dear Boss” letter. They published a facsimile in the hope that someone might recognize the handwriting, but were unsuccessful.

Unfortunately, while it is true that both were probably written by the same person, it is also possible that that person was not Jack the Ripper. Since the start, some investigators believed that these letters were the work of journalists, specifically either Fred Best or Thomas Bulling. They had access to confidential information and wanted to keep interest in Jack alive.

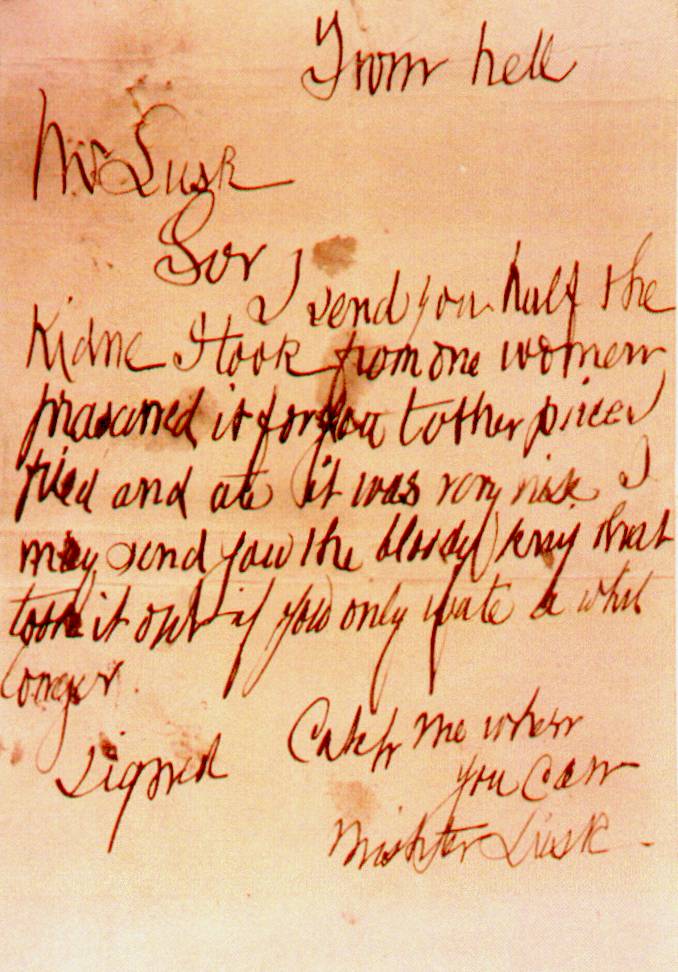

Indeed, it is quite feasible that all the correspondence purported to be from Jack the Ripper was actually written by other people who wanted to be part of the sick charade that surrounded the murders. One more letter merits inclusion, though, because it came with a grisly accessory – part of a human kidney. This missive was addressed “From Hell” and was sent to George Lusk, chairman of a volunteer vigilante group called the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee. It read:

“Mr Lusk,

Sir

I send you half the Kidney I took from one women preserved it for you tother piece I fried and ate it was very nice. I may send you the bloody knife that took it out if you only wate a while longer

signed

Catch me when you can Mishter Lusk”

The handwriting in this letter was definitely not the same as the first two. Obviously, the implication was that the kidney belonged to the fourth victim, Catherine Eddowes. Dr. Thomas Openshaw of the London Hospital examined the organ and concluded that it was, indeed, human. Subsequently, Openshaw received his own Ripper letter where Jack lamented that “coppers spoilt the game” and foiled his attempt to claim another victim near Openshaw’s hospital.

The Final Victim – Mary Jane Kelly

Jack the Ripper saved his most vicious kill for last. His victim was Mary Jane Kelly, an Irish working girl who, at only 25 years old, was much younger than the other murdered women. Also unlike the rest, she was killed in her home rather than on the street.

Kelly’s body was discovered on the morning of November 9 at her lodging at 13 Miller’s Court by Thomas Bowyer, her landlord’s assistant. Bowyer came round to collect the rent and, even though he was a former soldier, he was left stunned by the scene of ineffable horror that awaited him.

First thing he noticed was the broken window. Inside, the room was absolutely covered in blood. On the table he saw piles of meat, not realizing in the moment that they were human flesh. On the bed there was the body of Kelly which had been so grotesquely maimed and mangled that it barely looked human anymore.

According to the doctor’s estimation, it would have taken around two hours to inflict those atrocities upon Mary Kelly. It showed the world just how depraved Jack the Ripper could be when he had all the time and privacy he wanted.

Police surgeon Dr. Thomas Bond detailed the extent of her injuries in his report: “The whole of the surface of the abdomen and thighs was removed and the abdominal cavity emptied of its viscera. The breasts were cut off, the arms mutilated by several jagged wounds and the face hacked beyond recognition of the features. The tissues of the neck were severed all round to the bone.”

The Investigation

On the other side of the law, the London police force was engaged in one of the most ample investigations in its history. Thousands of people were interviewed and hundreds of leads were chased down, yet police were heavily criticized by the public and the media for failing to apprehend the killer.

The inquiry was initially handled by Whitechapel’s H Division of the Criminal Investigation Department, but was soon taken over by Scotland Yard detectives. Chief among them was Detective Inspector Frederick Abberline who was put in charge of the case because he previously worked for H Division for 14 years and it was thought that his local knowledge would prove invaluable.

A frequent criticism throughout the investigation concerned police refusal to offer a reward for information. Authorities were accused either of not taking the case seriously or not caring what happened in a poor district full of immigrants like Whitechapel. In reality, this lack of reward was a new Home Office policy instituted a few years earlier.

If you’re watching this video, you are probably already aware that the police never caught Jack the Ripper. That being said, there are two curious moments in their investigation that are worth discussing.

First is a report by surgeon Thomas Bond. He was asked for his opinion on the killer’s medical knowledge, but Bond ended up writing an 11-point essay which is sometimes regarded as the first ever criminal profile. Curiously, Bond vehemently disagreed with Dr. Phillips’s assertion that Jack the Ripper had a medical background. He didn’t even think the killer had “the technical knowledge of a butcher or horse slaughterer.”

Moreover, Bond had no doubt that the five women were killed “by the same hand.” He concluded that Jack the Ripper was cool, daring, middle-aged, quiet, respectably dressed, and inoffensive looking. He believed the killer wore a cloak or overcoat in order to conceal the blood stains after the murders. Bond said that, in each case, the mutilation was the Ripper’s main goal and that Jack might have suffered from homicidal impulses brought on by satyriasis, a condition better known today as hypersexuality or nymphomania.

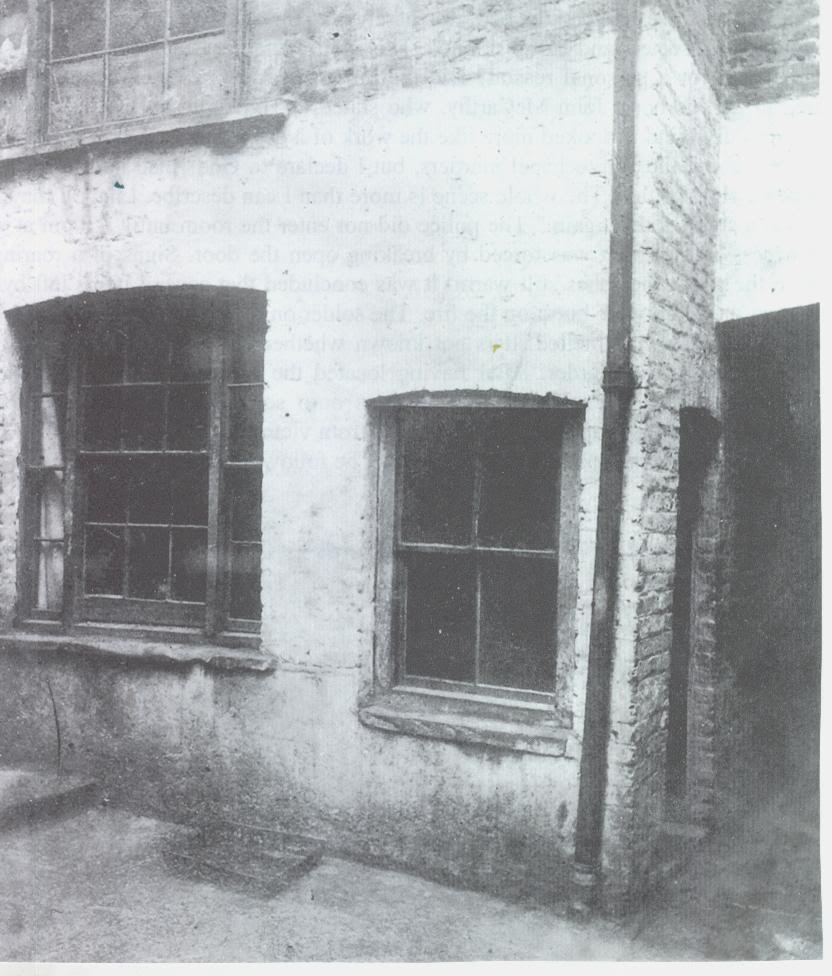

The second moment concerns the only clue that Jack the Ripper left following a kill. After he had murdered Catherine Eddowes, he took her apron. Police later found the bloody garment in a stairwell on Goulston Street. Right above it was a piece of graffiti written in chalk which read “The Juwes are the men that will not be blamed for nothing.” Police saw it, copied it down and, on the orders of Police Commissioner Charles Warren, wiped it clean. At a time of skyhigh racial tensions, he feared that the text might incite a violent riot.

Image: Goulston Street Graffito

Much debate still goes on regarding whether the police acted properly by erasing possible evidence and whether the graffiti was actually a message from Jack the Ripper or just a random anti-semitic scrawl unconnected to the crimes.

More Murders?

The five dead women we have mentioned are referred to by ripperologists as the Canonical Five and are, generally, considered Jack’s only victims. However, given the uncertainty surrounding everything else related to the Ripper, it’s not surprising that people think he may have killed others.

First, there were two slayings which took place in Whitechapel before that of Mary Nichols.The first victim was Emma Smith and the second was Martha Tabram. Smith survived her attack long enough to tell police she was assaulted by two or three men, making it more likely that she fell prey to gang violence. Tabram, however, died after being stabbed 39 times. Her kill had the viciousness of Jack the Ripper, but investigators were, ultimately, convinced that her death was unrelated because her throat wasn’t cut and she wasn’t mutilated afterwards. Even so, it wouldn’t be completely unheard of for a serial killer to evolve his modus operandi and increase in brutality as he gained more experience and confidence.

Four more suspicious deaths occurred in 1888 and 1889 which were added to the Whitechapel Murders. However, they were considered unrelated because they lacked the savage disfigurement of the Ripper.

That being said, one of those victims was just the torso of a woman. That certainly sounds vicious enough to be the work of Jack but, as it happened, four other torsos had been found around that time, just not in Whitechapel. Only one of the victims of the so-called “Thames Torso Murders” was identified as Elizabeth Jackson. Some believe these were all the work of Jack, while others feel they belonged to a second maniac who was active at the same time as the Ripper.

Who Was Jack?

Who was Jack the Ripper? That’s the million dollar question and historians, scholars, criminologists, authors, and police officers have put forward over a hundred suspects.

Inspector Abberline strongly suspected George Chapman, a Polish immigrant and a convicted serial killer who was hanged for three poisonings. Chapman, real name Seweryn Kłosowski, had minor surgical knowledge and arrived in London shortly before the killing spree started. He also left for America in 1891, a few years after the murders stopped. However, Chapman used poison and criminologists don’t believe a killer would change their modus operandi to such an extent.

Another convicted serial killer suspected of being Jack was Dr. Thomas Neill Cream. He was also a poisoner and, according to records, he was in prison in America during the killing spree. All available evidence should dismiss Cream as a candidate, yet he remains a popular choice solely based on the story that, while being hanged, Cream’s last words allegedly were “I am Jack…”

A more plausible suspect was Aaron Kosminski, a Jewish barber who emigrated from Congress Poland sometime in the early 1880s. He was considered a strong candidate by several authorities of that era. Sir Melville Macnaghten, Assistant Commissioner of the London Metropolitan Police, wrote in memoranda that Kosminski had “strong homicidal tendencies” and a “great hatred of women, especially of the prostitute class.” Chief Inspector Donald Swanson wrote that the only witness who got a good look at the Ripper’s face (doesn’t specify who, but presumably either Schwartz or Lawende), refused to testify against him because they were both Jewish. And although we’re not exactly sure on the date, sometime around 1890 Kosminski was committed to an insane asylum which lines up with the murders stopping.

Modern science seemingly came to the rescue when a paper published in the Journal of Forensic Sciences boldly proclaimed that Aaron Kosminski was Jack the Ripper based on DNA. The authors alleged that a semen sample obtained from the shawl of Catherine Eddowes, the fourth victim, was DNA matched to a living relative of Kosminski. This study, however, was heavily criticized by other scientists who found many faults with it. Even the provenance of the shawl is in doubt. The original inventory done in 1888 lists, in detail, over 30 items of clothing and possessions that Eddowes had on her at the time of her murder, yet there is no shawl among them. So while Kosminski remains one of the top suspects, the matter is yet to be settled.

In the same memoranda, Assistant Commissioner Macnaghten named Montague Druitt as his favored suspect. He asserted that Druitt was “sexually insane” and was suspected of being the Ripper even by his own family. Druitt committed suicide a month after the murder of Mary Kelly, giving a reason why the murders stopped. Macnaghten’s appraisal placed Druitt at the top of the suspect list of many ripperologists, but it seems to be based mostly on incorrect facts and hearsay. Inspector Abberline dismissed Druitt as a suspect and, decades later, researchers placed Druitt in different parts of the country for some of the murders.

Going by viciousness alone, a man named Frederick Bailey Deeming seemed to be the most likely culprit. Deeming was hanged in Australia in 1892 for killing his second wife, only to be later discovered that he had also murdered his first wife and their four children by cutting their throats. He was certainly capable of inflicting the gruesome horrors of the Ripper, but records of his movements in 1888 are spotty, at best. They seem to indicate that Deeming was in South Africa at the time.

These are just a few of the more sensible suspects. There are many more out there. Some believe the killings were the work of a masonic conspiracy involving the royal family whose goal was to protect Prince Albert Victor and that the killer was either the prince himself or the Queen’s physician, Sir William Gull. Others opine that the murderer was Lewis Carroll, author of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland or the post-impressionist painter Walter Sickert.

Some believe that Jack the Ripper was, in fact, Jill the Ripper, and that the killer was a woman. This theory started with Inspector Abberline himself. Some of the suspects included women of the era who had been convicted of heinous murders such as Mary Pearcey and Lizzie Halliday.

We could keep doing this all day and we would still not run out of suspects. Ultimately, there isn’t sufficient evidence to identify, beyond a shadow of a doubt, any person as Jack the Ripper. This anonymity surely helped bolster his infamy as here we are, 130 years after his ghastly killing spree, still talking about it. And we are hardly the only ones – books, movies, and TV shows that revolve around the Ripper murders are still popular today. So that just leaves us with one question – who do you think was Jack the Ripper?