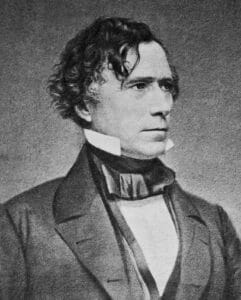

Franklin Pierce, who pronounced his surname as “purse”, is consistently ranked as one of the worst Presidents in American history. His administration, which occurred in the decade preceding the American Civil War, is cited as one in which the causes of that war were exacerbated by the President’s policies. Though a native of New Hampshire, Pierce generated considerable enmity from his fellow New Englanders, largely due to his stand against the abolitionists that demanded an end to slavery. His political skills were unequal to the challenges he faced in office, and his own Democratic Party refused to nominate him to run for a second term, an almost unheard of circumstance in American politics.

His life was one of tragedy and melancholy. His wife’s family disapproved of him. It took eight years of courting before she could be persuaded to marry him. Jane Means Appleton, who eventually became his wife, was deeply religious, hated politics, despised Washington, and opposed the consumption of alcohol to the point she was active in temperance movements in antebellum New England. Pierce, on the other hand, thrived in political and legal maneuvers, drank to excess, and served in several posts in Washington. His views on religion can be surmised by his refusal to take the oath of office as President by swearing on a Bible. He affirmed his oath with his hand on a lawbook.

Franklin Pierce entered the Presidency prone to bouts of depression, his wife having refused to accompany him to Washington. Throughout his four years in office, he drank to excess. His was a gloomy, unhappy White House. He may well have been one of the worst presidents in history. He may also have been the saddest, or at the very least, the unhappiest.

Bred to Politics

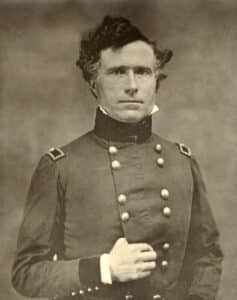

Franklin Pierce’s climb to the Presidency included what would in a much later day become known as getting all of his tickets punched. His experience in politics began in the most democratic of all American forms of government, the New England town meeting. Eventually he served in the New Hampshire State Legislature, where he rose to the position of Speaker of the House. Later he served in the United States House of Representatives, and still later in the United States Senate. He served over a decade in the New Hampshire State Militia, reaching the rank of Colonel, and during the Mexican-American War he held a commission as a brigadier general in the Regular Army, serving with distinction. By the time he came under consideration for the Presidency, his resume was impressive, to say the least. But, it did not begin that way.

Franklin Pierce was born in 1804 in Hillsborough, New Hampshire. He was the fifth of what would be eight children born to tavern keeper and American Revolutionary War hero Benjamin Pierce and his wife, Anna. According to family lore, Franklin was born in the log cabin then occupied by his parents and siblings. However, the large Pierce homestead in Hillsborough, which still stands, is advertised as his childhood home. Except for when he was away at school, the house was Franklin’s home until his marriage in 1834.

Pierce was a reluctant student in his youth. Sent by his father to attend the town school in Hancock, some twelve miles distant, Franklin ran away, returning to the family homestead in Hillsborough. His father, by then a state legislator and prominent politician, forced him to return to school. Two of Franklin’s elder brothers, both veterans of the War of 1812, counseled their younger sibling to focus on his studies, ignoring any pangs caused by being away from home. Franklin heeded their advice, eventually attending Phillips Exeter Academy in Andover, and then enrolling in Bowdoin College in Brunswick, Maine. While there, he befriended a young Nathaniel Hawthorne, as well as other young men with whom he would later serve in Congress.

After graduating from Bowdoin with a Bachelor of Arts degree, Franklin read the law under the guidance of attorney and former governor of New Hampshire Levi Woodbury, in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. He later attended law school in Northampton, Massachusetts, and passed the bar in New Hampshire in 1827. He established a legal practice in Hillsborough that year.

In the meantime, Benjamin Pierce had continued to advance his own political career, as a pro-Andrew Jackson Democrat. In March, 1827 Benjamin was elected as governor of New Hampshire. His son Franklin likewise sought political office, and won the position of moderator of Hillsborough’s Town Meeting in the elections of 1828. He won the office again the following five years. In 1829, Franklin also won election to the State Legislature. Two years later, with the Democrats holding a clear majority in New Hampshire, Franklin Pierce was elected as Speaker of the State House of Representatives. He was 27 years of age, and the rising star of New Hampshire politics.

Courting Jane

How and when Jane Appleton became acquainted with Franklin Pierce is disputed. One claim from family lore holds that Franklin introduced himself to Jane during a thunderstorm, when he warned her against seeking shelter beneath a tree. An introduction by one of his Bowdoin professors is another version often cited. However it happened, historians agree it was not welcomed by Jane’s family.

The Appleton’s were wealthy, politically connected, anti-slavery, and pro-temperance. Jane was well-educated, well-read, and possessed of musical talent. Refined and cultured, she was also deeply religious with puritanical leanings, which did little to alleviate her condemnation of demon rum. While she obviously found some attraction in the young Franklin Pierce, her family did not share her enthusiasm. They found him coarse, beneath her station, of the wrong political bent, ill-mannered, and too prone to indulge in alcohol.

Even worse, his Episcopalian leanings were anathema to their Calvinist beliefs. They also looked askance at his obvious political ambitions as being low-minded and uncultured. To the Appleton’s, Franklin Pierce came up well short of their ideal match for Jane.

Franklin Pierce did not view his political ambitions as a personal quest for power and influence. Following the examples set by his father and others, he viewed public service through political office as a noble cause. Though he disagreed with the political views of the Appleton’s and others in New England, including the abolitionists, he did not view such disagreements as being exclusive of personal relationships. He continued to court Jane Appleton despite the growing disparity of views dividing American politics, especially the issues of slavery, its containment in the states in which it already existed, and its exclusion from new states seeking admission into the Union.

Pierce’s growing influence in New Hampshire politics brought with it an elevation in social affairs as well. By 1832, his position, as well as Jane’s advancing age, led her family to regard his courtship with more welcoming attitudes. Jane was by then 26 years of age, considered old to be unmarried in that time and place. That year Franklin was elected to the US House of Representatives, as he neared the end of his term as Speaker of the House in the State Legislature. Jane agreed to marry the politician, and they were wed on November 19, 1834. Following their marriage, the new bride accompanied her husband to Washington, and the boarding house where he lived while Congress was in session.

Much has been made of Franklin Pierce’s drinking, with some biographers expressing the belief that he enjoyed the bottle to excess for most of his adult life. Others have claimed that Pierce did not indulge in heavy drinking until later tragedies had overwhelmed him. That Jane, a teetotaler and temperance supporter, agreed to marry him would seem to indicate she did not consider his drinking to be a serious problem, at least not at the time they were married. Or, perhaps she believed that she could reform him. Whichever it may have been, it was not to be a happy marriage.

In the House of Representatives

In 1833, Franklin Pierce went from being the leader of the Democratic faction in the New Hampshire legislature to being a junior Representative in the United States Congress. The Democrats held the majority in 1833, though Pierce on more than one occasion voted against party measures. He opposed using federal money to fund improvements in infrastructure, such as roads and canals, believing such efforts to be within the purview of the individual states. He also became a leading voice against the rising influence of the abolitionists in Congress, viewing them as agitators. Pierce defended the rights of the states over the power of the federal government regarding slavery, which he considered to be a legal issue of property, rather than a moral issue of human rights.

Pierce also opposed the religious cast of abolitionists, who decried the southern slaveowners as sinners. To Pierce, such “religious bigotry” was abhorrent. He publicly condemned slavery as a “social and political evil”, expressing the wish that, “it had no existence on the face of the earth”, but also expressed, “the abolitionist movement must be crushed or there is an end to the Union”.

Pierce was re-elected to the House in 1836. By then, he lived in Washington alone while Congress was in session. Jane had found the social scene in Washington to be unbearable. The manners and behavior of the city were repugnant to her New England sensibilities, and in late 1835, she left the city to reside with her mother. She cited her failing health as an excuse to leave Washington. Franklin purchased a home in Hillsborough, New Hampshire, though she found that residence equally untenable during the periods when her husband was absent in Washington.

On February 2, 1836, Jane gave birth to a son the Pierce’s named Franklin Jr. The infant died three days later on February 5. Both parents were thrust into deep melancholy. Franklin delved deeply into his work, while Jane found continued residence in Hillsborough to be unthinkable. The couple purchased another home, in Concord, New Hampshire, in 1838. By then, Franklin was no longer sitting in the House of Representatives. In 1837, Franklin Pierce had been elected to the United States Senate by the New Hampshire legislature.

The Troubled Senator from New Hampshire

Franklin Pierce entered the US Senate during emotionally trying times. His wife had not recovered from the loss of their son, and had begun to complain of several chronic health issues. His own mental well-being had been similarly affected, and among his cronies in Congress, he began to develop the reputation of being a heavy drinker, during an age when excessively heavy drinking, at least to modern eyes, was the norm.

Nonetheless, he was considered an able Senator, reliably supporting or opposing legislation along party lines. He also demonstrated an ability to bestow political patronage. In one example, he appointed his long-time friend Nathaniel Hawthorne as a custodian of coal and salt in the Port of Boston. The position, ostensibly in the Boston Customs House, was what in a later day be known as a no-show job. The sinecure provided Hawthorne with an income, demanded little of his time, and supported the writer as he produced the short stories collected into the volume Twice Told Tales, his first major literary success.

Meanwhile Jane had come to the conclusion that the death of their infant son had been Divine Retribution for the sinful and profligate ways of her husband. Reinforced by relatives from her mother’s family, Jane wrote her husband letters in which all of their woes were laid plainly at his feet, punishment for his choice of career. To Jane, even her husband’s drinking was an effect, rather than a cause. She joined him in Washington, made some of the demanded social appearances, and soon fled back to her family. During her visits to Washington she exhorted her husband to exit politics.

In 1839, Jane and Franklin Pierce welcomed a second son into the world, whom they named Frank Robert Pierce. Young Frank provided further motivation for Jane to convince her husband to enter another career. By late 1840, a presidential election year, Franklin had come to agree with his wife. The Democrats lost both the White House and the Senate majority in that year’s election. Franklin was also term limited by New Hampshire law, meaning he could not run for re-election for another term as Senator at the end of his current term.

By then Jane and Franklin had another son, Benjamin Pierce, born April 13, 1841. The presence of two sons with Jane at the Concord home provided further inducement for Franklin to leave the Senate. Franklin Pierce resigned from the Senate in early 1842, and returned to the practice of law in Concord, New Hampshire. He had no intention of retiring from politics, as subsequent events demonstrated, though to his wife, he promised he would focus on the practice of law.

Struggling Through Tragedy

In Concord, Franklin Pierce entered into a law practice which enhanced his reputation as a capable attorney while affording him the time to remain active in state political circles. Jane enjoyed her status as the wife of a well-regarded lawyer and former Senator. She became an active participant in Concord’s social scene, and entertained numerous notable guests in their home, including writers, legislators, educators, and other celebrated personages. For a brief time, all was well in the Pierce household and marriage.

Then in 1843, an epidemic of typhus swept through Concord. Before it was over it had claimed the life of young Frank Robert Pierce, at the age of four. Both Franklin and Jane were again stricken with the deep grief caused by the loss of a child. Jane took solace in prayer, penitence, and the presence of her sole surviving child. Franklin sought relief from his pain through work, party politics, and increasingly, the bottle.

Franklin hired a married couple to attend to the household duties at Concord, freeing Jane of her domestic responsibilities and allowing her to spend all of her time with their surviving son, Benjamin. She devoted herself to her son completely, ignoring social invitations and activities, and personally supervising his education in a strictly Puritan religious environment.

Franklin Pierce had promised his wife he would not accept political office, and though he served as the Chairman of the state’s Democratic Committee, he refused the office of Attorney General when offered it by President James K. Polk. A military appointment was another matter though. In 1846, after Congress declared war on Mexico, Pierce accepted a commission as a Colonel in the 9th Infantry Regiment of the United States Army. In early 1847, he was promoted to Brigadier General and sent to Vera Cruz under the command of General Winfield Scott. Pierce served with distinction in Mexico, and returned to Concord and a hero’s welcome in late 1847, following the American victory in the Mexican War.

He resumed the practice of law, reassured Jane regarding his lack of further political ambition, and appeared for all intents and purposes, to be content with his lot. In 1852, the Democratic Party prepared for the presidential election with a June convention in Baltimore, Maryland. The party was deeply divided, largely over the issue of slavery and its expansion into new states and territories. Among the candidates for the nomination for President were Sam Houston of Texas, Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri, and James Buchanan of Pennsylvania. Pierce remained in New Hampshire, far from the brokering and deal-making on the convention floor. Yet, he allowed his supporters in the party to enter his name as a candidate after several ballots failed to select a nominee.

On the 49th ballot of the contentious gathering, Franklin Pierce acquired the needed votes to become the Democratic nominee for President. A subsequent ballot named William Rufus King as his running mate. Pierce received the news via a telegram to his Concord home. When Jane heard the news, she collapsed in a faint.

Pierce’s opponent was Winfield Scott, who had been his commanding officer in Mexico. Scott, though a celebrated war hero for his actions in Mexico, proved an unpopular presidential candidate. Franklin Pierce won the election handily, achieving a majority of the popular vote and a landslide in the Electoral College. It was the peak of his political career. Before he was to enter what historians rank as one of the nation’s worst presidential administrations, he was to suffer one more deep personal tragedy, from which neither he nor his wife would ever fully recover.

The Andover Railroad Accident

In December, 1852, Pierce, Jane, and their son Benjamin, nicknamed Benny, spent the Christmas holidays with Jane’s sister and her husband in Andover, Massachusetts. Jane’s sister was married to John Aiken, a textiles manufacturer and a leading benefactor of Phillips Academy, where Benny was scheduled to enroll. The Pierce’s were frequent guests of the Aikens, and the holidays were less tense than they may have been, given Jane’s displeasure over her husband’s return to politics. On January 6 1853, the Pierce family departed Andover by train for the journey to Concord, where Jane and Franklin were to prepare for their journey to Washington and the White House.

Benny, then 11 years old, was standing to get a better view out of a window when the train derailed just a few miles north of Andover. The car in which the Pierce’s rode went down an embankment, crushed by its own weight and the following cars. Benny was immediately entangled with broken wood and iron, which mangled his body and nearly decapitated him. The grisly accident occurred directly in front of his parents, and Franklin was later further traumatized by the necessity of identifying his dead son’s body. Benny’s body was returned to the Aiken home in Andover, where a funeral service was held before the President Elect’s son was conveyed to Concord for burial. Franklin Pierce accompanied his son’s body to Concord. Jane did not, remaining behind in Andover, unable to bear her grief.

Six weeks after the tragedy Franklin Pierce left Concord to journey to Washington and his inauguration as the 14th President of the United States. His wife accompanied him as far as Baltimore, where she remained as her husband took the oath of office. There were no inaugural balls, no celebration at the President’s Mansion. Despite the large crowd which swelled Washington to see the new President enter office, an air of gloom predominated. It would last for the rest of his Presidency.

The Shadow in the White House

Jane Pierce eventually joined her husband in Washington, though she never took much interest in the role of First Lady. For the rest of her life, she wore black. She summoned spiritualists to the White House in attempts to contact her dead son, and she wrote notes and letters addressed to him, describing the events of the day. To the Washington press, she became known as “The Shadow in the White House”. Eventually the phrase came to refer to the Pierce administration, as Franklin’s policies created more and more enemies.

Pierce’s Vice-President, William Rufus King, took his oath of office while in Cuba, the only American Vice-President to be inaugurated while on foreign soil. He was there in an attempt to recover his health, having contracted tuberculosis. The attempt failed. King died at his home in Alabama on April 18, 1853. His death removed Pierce’s important political links with Southern Democrats.

Pierce’s own policies and his fervent anti-abolitionism destroyed his standing with Northern Democrats. Having lost the support of his own party, his wife, and his Southern allies, Pierce’s administration was doomed to failure. By the last year of his administration, he was virtually an exile in the White House, though a defiant one. His support of the Fugitive Slave Act and the Kansas-Nebraska Acts alienated what was left of the coalition which elected him. Kansas erupted in bloody violence which the President was seemingly powerless to stop. The Democratic Party chose not to nominate him to run for a second term, and Pierce left the White House, and politics, in 1857.

In retirement, Pierce continued to voice his opinions, and became a staunch opponent of the Lincoln Administration during the Civil War. Yet, his was the proverbial voice in the wilderness. With Jane, he traveled extensively, visiting his friend Nathaniel Hawthorne in Europe, and writing for newspapers in England and the United States. He predicted the Civil War, as well as the racial strife which was to follow, but his warnings went unheeded. His former political allies and foes regarded him as a crank, and his drinking continued unabated. His alcoholism did not go unnoticed in the press.

Jane Pierce died in December, 1863, after a long period of decline due to tuberculosis. Franklin Pierce lived in retirement in New Hampshire until he succumbed to cirrhosis of the liver in October, 1869. His death was extensively covered in the nation’s newspapers, most of which noted his long career in public service, culminated by a failed Presidency. Unlike many other “failed” Presidents, such as John Adams and Harry Truman, his career has never been subjected to a favorable re-examination by historians. He remains widely regarded as one of the worst Presidents in American history. His was a life of service, deeply checkered with personal and professional tragedy, which ultimately ended in failure. Truly, the saddest of Presidents.