In 1993, Tommy Lee Jones famously gave this speech: “All right, listen up, ladies and gentlemen, our fugitive has been on the run for ninety minutes. Average foot speed over uneven ground, barring injuries, is 4 miles an hour. That gives us a radius of six miles. What I want out of each and every one of you is a hard-target search of every gas station, residence, warehouse, farmhouse, henhouse, outhouse and doghouse in that area. Checkpoints go up at fifteen miles. Your fugitive’s name is Dr. Richard Kimble. Go get him.”

That is taken from the smash hit movie The Fugitive, which went on to be nominated for seven Academy Awards and become one of the greatest action films of the 90s. It told the story of Dr. Richard Kimble, played by Harrison Ford, who was forced to go on the run after being falsely convicted for the murder of his wife when, in fact, the killer had been a mysterious one-armed man.

Some fans of the film might be unaware that The Fugitive was originally a television show back in the 1960s. Even fewer fans might know that the show may have been inspired by the sensationalistic, real-life murder trial of Dr. Sam Sheppard, who also stood accused of killing his wife.

Just to clarify, the creator of the original TV show, Roy Huggins, denied any connection between the two, although other people involved like the network executive who aired the show and the lawyer in the real case both argued that they were definitely related.

Whether Huggins was inspired by the real trial or not is besides the point, but it certainly would have been difficult for him not to be aware of it. In its day, there were few other better examples of a “media circus” than the Sam Sheppard trial. Even the United States Supreme Court decried the proceedings for having a “carnival atmosphere” and criticized the media for conducting “trial by newspaper” and concluding that Sam Sheppard was guilty before he had even been brought in for an interrogation.

So today we are exploring one of the most famous murder cases in American history, as we examine the death of Marilyn Sheppard, followed by the arrest, the trial, and the long road to exoneration of her husband, Dr. Sam Sheppard.

Portrait of a Perfect Family

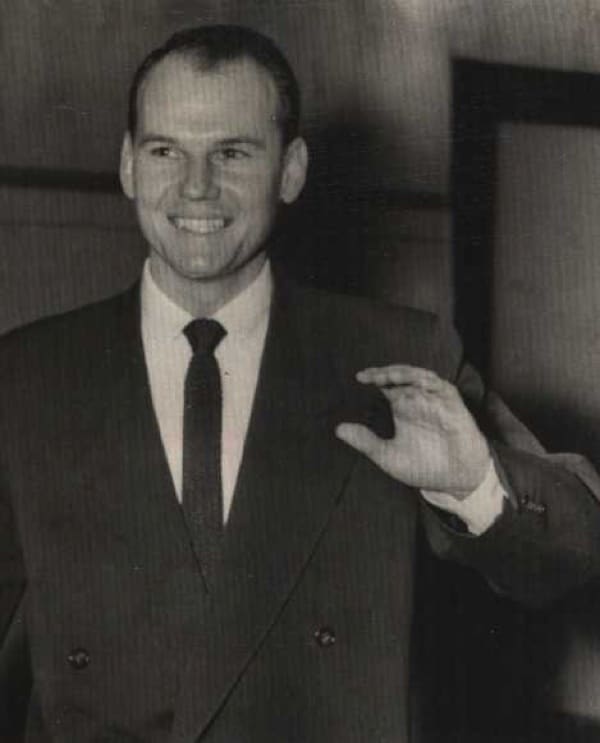

Sam Sheppard was born on December 29, 1923, in Cleveland, Ohio. Right from the outset, he seemingly possessed everything he needed to lead a successful life. He came from a good family, he was smart and athletic, and he was voted “Most Likely to Succeed” in his senior year of high school. Once he graduated, he decided to follow in the footsteps of his father, Richard Allen Sheppard, and become a doctor of osteopathic medicine, so he enrolled at the Los Angeles College of Osteopathic Physicians and Surgeons.

Just a quick sidebar here for the sake of clarity. The American medical world makes a clear distinction between doctors of osteopathic medicine, also known as osteopathic physicians, and people who are called simply osteopaths. The former require a degree from an approved medical school, and are able to practice the same scope of modern medicine as medical doctors, which includes performing surgeries and writing prescriptions. Osteopaths do not.

In 1945, Sheppard obtained his degree in osteopathic medicine and was now Dr. Sam Sheppard, D.O. For a while, he stayed in Los Angeles and worked at the County Hospital. However, in 1951, he went back to Ohio to join the family practice. His father had purchased the Washington Lawrence mansion in Bay Village, an affluent suburb of Cleveland, and turned it into an osteopathic medical center called the Bay View Hospital.

During his time out in Los Angeles, Sam Sheppard had also married his high school sweetheart, Marilyn Reese, and the couple already had a young son named Samuel Reese Sheppard by the time they returned to Ohio. They also had a dog named Koko, who actually went on to play an important role during the trial. Nobody had heard the dog bark the night of the crime, so the prosecution argued that meant there were no strangers in the house.

Anyway, the point here is that the Sheppards seemed to have a charmed life. But as was revealed later during the trial, all was not well behind closed doors. Dr. Sheppard was having an affair with a nurse from his hospital named Susan Hayes and, according to multiple testimonies, Marilyn was aware of this. By the doctor’s own admission, the couple were having marital troubles, but they intended to work them out and divorce was never really considered, especially since Marilyn was already pregnant with their second child.

Night of the Murder

On the evening of July 3, 1954, the Sheppards were entertaining guests over at their house. They were the Aherns, a family that lived in the neighborhood. After dinner, the group went to the living room, where they started watching the movie Strange Holiday on TV. At one point, Sam Sheppard fell asleep. Around midnight, the Aherns went home and Marilyn went upstairs to bed, letting Sam sleep in the living room. A few hours later, Marilyn Sheppard was dead, after having been brutally bludgeoned in her own bed.

The first person to hear of this was a man called Spencer Houk, who was the Mayor of Bay Village and a friend of the Sheppards. At around 5:40 a.m., he received a call from a distressed Sam Sheppard, who told him :“For God’s sake, Spen, get over here quick. I think they’ve killed Marilyn.” Houk and his wife were first on the scene, followed closely by the police who arrived at the Sheppard home shortly after 6 a.m.

Inside the house, investigators found a trail of blood leading to Marilyn Sheppard’s body, as well as some signs of an apparent robbery. Seven-year-old Samuel had been sleeping in his room, unaware of the night’s events, and an uncle came and picked him up. Meanwhile, Sam Sheppard Sr. displayed various cuts and bruises which resulted, according to him, from a fight with the killer, whom he only described at the time as being “bushy-haired.” Showing signs of shock, he was sedated and sent to the hospital to get treated for neck injuries.

Back at the house, the coroner, Dr. Sam Gerber, arrived at around 8 a.m., and while going over the crime scene, he immediately began suspecting Sheppard of murdering his wife. A few hours later, police interrogated the osteopathic physician. According to his version of events, he woke up during the night after hearing his wife screaming his name. He rushed upstairs where he saw a stranger standing over the body of Marilyn. The two fought, but the killer got the upper hand and briefly knocked Sheppard unconscious before making a run for it. The doctor awoke after a short period, he went to check on his son who was sleeping in his own room, and then ran outside, looking for the intruder. Sheppard caught up to the killer on the shore of nearby Lake Erie. They started brawling again, but the intruder proved stronger and knocked Sheppard unconscious once more. By the time the doctor came around, the bushy-haired stranger had stolen his shirt and disappeared, so Sheppard went inside and called Spencer Houk.

The police weren’t really sold on his story. There were few signs of a break-in inside the house, nobody else heard or saw the struggle, and Dr. Sheppard’s description of the killer was so vague that, at certain points, he wasn’t even sure if it was a man or a woman. Like Dr. Gerber, they soon started suspecting Sam Sheppard of murdering his wife.

So did the newspapers. Unsurprisingly, by the next day, the death of Marilyn Sheppard was on the front page of every paper in Cleveland and, a few days later, in all of Ohio. Cars started lining up as people wanted to drive past the infamous Sheppard house. Less than two weeks after the murder had occurred, the media had already, more or less, proclaimed Sam Sheppard to be guilty.

Things got significantly worse for the doctor during the inquest, when his relationship with Susan Hayes was brought up. Initially, he denied having an affair with her, but she later fessed up to the whole thing when she was interviewed. This not only proved that Sheppard had lied to the police, but it also gave him a motive for wanting his wife out of the picture. Once word of this got out, the Cleveland Press ran a story with the headline “Why Isn’t Sam Sheppard in Jail?” on July 30, 1954. Later that same day, police charged and arrested the doctor for the murder of Marilyn Sheppard.

Trial of the Century

What followed was one of the most publicized trials in American history. The preliminary hearing took place in the first half of August, after which Sheppard was released on bail on August 16. He didn’t know it yet, but that would be the doctor’s last day of freedom for almost a decade. The very next day, the grand jury returned an indictment of first-degree murder, so Sheppard was arrested again.

The trial itself started halfway through October, after the judge in the case, Edward Blythin, rejected a request from the defense to move the trial out of Cleveland due to the extensive publicity it received. Years later, the U.S. Supreme Court deemed this a mistake and criticized the judge for failing to “control disruptive influences in the courtroom.” Perhaps the most egregious examples were situations where he did not dismiss the jury even though it would have been warranted. They had not been sequestered and were therefore exposed to sensationalized radio broadcasts that would have shaped their opinion of Sam Sheppard. On one particular occasion, two jurors admitted to listening to a broadcast that said that a woman had been arrested in New York, claiming that she was the mistress of Sam Sheppard and that they had a child together. The judge found out about this and allowed the persons to continue serving on the jury and, worst of all, the claim was later proven false.

The prosecution was led by John Mahon. During the trial, there was not a lot of actual evidence to indicate that Sheppard was the culprit. The prosecution’s strategy mainly involved using the doctor’s affair to establish a motive and pointing out the inconsistencies in his own flimsy account of the events. As far as Sheppard was concerned, he stuck to his original story, placing the blame on a bushy-haired man.

The jury retired on December 17. They deliberated for four days and returned a verdict of guilty of second-degree murder. The judge then sentenced Sam Sheppard to life in prison.

Meanwhile, the tragedies kept on coming for the Sheppard family. Sam’s father, Dr. Richard Allen Sheppard, was slowly dying of stomach cancer. His mother, unable to cope with seeing her husband wither in front of her and her son sent to prison, committed suicide on January 7, 1955. His father succumbed to his illness less than two weeks later.

At the very least, Sam Sheppard still had his lawyers fighting for him. His defense attorney, William Corrigan, secured the services of an expert criminologist from California named Dr. Paul Kirk, who conducted another investigation of the crime scene. His final report concluded that the killer was left-handed, unlike the doctor, and displayed an extreme hatred of the Sheppards. He found the doctor’s version of events to be plausible and expressed his belief that there was blood in the bedroom that belonged to neither Sam or Marilyn Sheppard. Based on his report, Corrigan filed a motion for a new trial, but it was dismissed by the Eighth District Ohio Court of Appeals, a decision later affirmed by the Ohio Supreme Court.

The Road to Freedom

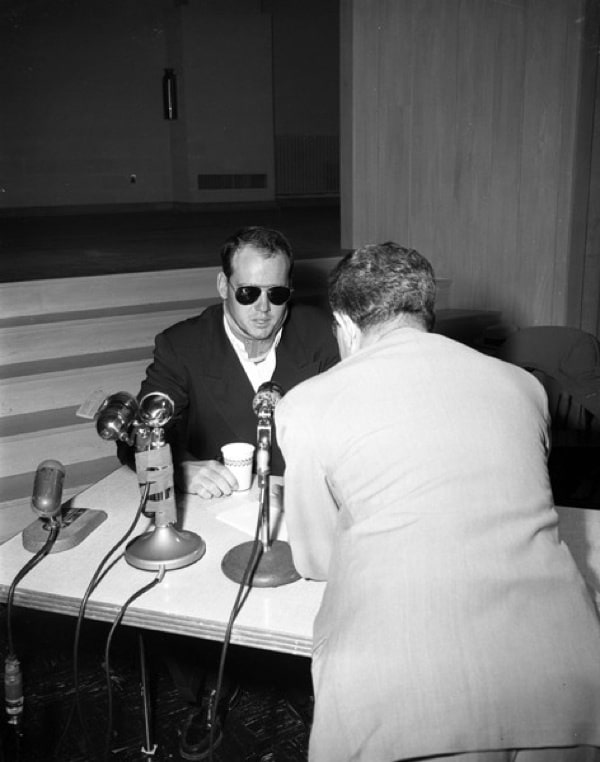

It seemed like it was the end of the road for Sam Sheppard, as the doctor began serving his sentence in a maximum security prison. But his lawyers still believed they had a shot of winning an appeal, not based on new evidence, but on the prejudice shown against their client during the original trial. William Corrigan kept fighting for Sheppard, up until his own death in July, 1961. Afterwards, the case was taken up by an up-and-coming attorney named F. Lee Bailey. For most other lawyers, a case like that of Sam Sheppard would, undoubtedly, represent the highlight of their careers, but for Bailey, it was just the start. He would go on to be involved in other high-profile suits including the Patty Hearst trial, the Boston Strangler and, most famous of all, the O.J. Simpson case.

In 1963, Bailey filed a petition for a writ of habeas corpus in federal court on behalf of his client, arguing that all the biased publicity against Sheppard violated his right to due process. Of course, Sheppard’s lawyers had already been saying this for years, but this time Bailey had some new evidence which tainted the presumed objectivity of the trial judge, Edward Blythin. This involved testimony from people at the courthouse to whom Blythin expressed his belief that Sheppard was already guilty during the trial or before it had even started. Most notable of all was crime journalist Dorothy Kilgallen, who mentioned that Judge Blythin once called her into his chambers and, during their conversation regarding Sheppard, the judge said “It’s an open-and-shut case. He’s guilty as hell.”

Bailey’s petition was accepted in July 1964, by Federal District Court Judge Weinman who dismissed the original trial as a “mockery of justice.” After almost ten years in prison, Sam Sheppard was a free man once more, but freedom could have easily been snatched away from him again. A habeas corpus meant that his imprisonment had been ruled to be unlawful, it did not declare him innocent of his crime and the prosecution had plenty of time to file new charges. But even before that, they launched an appeal on Weinman’s decision, which was approved in 1965 by the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals, thus reversing the ruling of the federal judge. It looked like Sheppard would be headed back to prison, but then Bailey filed his own appeal. Basically, it was a game of one-upmanship until, inevitably, the case reached the highest court in the land – the United States Supreme Court.

The case of Sheppard v. Maxwell started in February, 1966. It ended on June 6, with a vote of 8-1 in the doctor’s favor. The Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren found that the trial judge had failed to “protect Sheppard sufficiently from the massive, pervasive and prejudicial publicity that attended his prosecution” and that the doctor “did not receive a fair trial consistent with the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.”

This was all good news for Sheppard but, once again, this simply invalidated the previous trial, it did not exonerate him of the murder. The prosecution filed new charges and another trial started in November of that same year. This one, however, went a little different. Bailey was far more aggressive during cross-examination and was able to discredit some of the previous testimonies for not being objectively incriminating against his client. The attorney was also able to introduce as evidence the report from criminologist Paul Kirk who expressed his belief that a left-handed third person had been in the Sheppard bedroom on the night of the murder, and he also avoided putting Sam Sheppard on the stand, knowing that the doctor’s vague story about the bushy-haired attacker was not particularly believable. All of Bailey’s hard work paid off and, on November 16, the jury found Sam Sheppard not guilty of the murder of Marilyn Sheppard.

New Life

Finally, after over 12 years, Sam Sheppard had been officially exonerated of killing his wife. Now free, he tried to get his life back on track. While in prison, he had started communicating with a German divorcée named Ariane Tebbenjohanns, and the two got married very soon after his release in 1964, before his second trial even started. The marriage did not last very long, however, ending in divorce in 1968. Tebbenjohanns claimed that Sheppard drank a lot and that, on occasion, he had threatened her physically.

Indeed, things did not go smoothly for the doctor after his release from prison. He wanted to start practicing medicine again, but he soon discovered that being incarcerated for ten years had a significant impact on his skills. He obtained a position with the Youngstown Osteopathic Hospital in Youngstown, Ohio, but was forced to resign in 1968 after making mistakes during surgery that caused the deaths of two of his patients. Both he and the hospital were hit with wrongful death suits, making it hard for him to find a position elsewhere.

Following his divorce and his resignation, Sheppard was struggling with alcoholism and depression. He moved to a suburb of Columbus called Gahana where he intended to open a small medical office, but fate had a different career in mind for him – professional wrestling.

Yes, we’re serious. In Gahana, Sheppard made the acquaintance of a man named George Strickland, who was a pro wrestler. He convinced the doctor that his notoriety could make him a hit in wrestling, especially if he played a villain. Therefore, in August 1969, at the age of 45, the doctor who had once been accused of murdering his wife had his first pro wrestling match. Strickland usually acted as his manager or tag partner, and he even became Sheppard’s father-in-law in real life after the doctor married his 20-year-old daughter, Colleen Strickland.

Unfortunately, Dr. Sheppard’s career inside the squared circle lasted less than a year. His excessive drinking took a heavy toll on his health, and on April 6, 1970, Sam Sheppard died aged 46. Initially, cause of death was thought to be liver failure, but it was later determined to be a type of brain damage called Wernicke encephalopathy, also as a result of his alcoholism.

Who Did It?

Since Dr. Sam Sheppard was found “not guilty” in his second trial, this left the question of “Who killed Marilyn Sheppard?” unanswered. After his death, it was his son, Samuel, who continued the fight for justice for both of his parents: finding his mother’s killer and clearing his father’s name.

During the mid 90s, Samuel filed a suit for wrongful imprisonment against Cuyahoga County on behalf of his father. This led to the exhumation of both Sheppards to collect samples for modern DNA tests. One report which was used by his lawyer during the trial seemingly excluded Sam Sheppard as the source of the blood found at the crime scene.

We might not have mentioned him so far, but the truth is that there had long been a viable second suspect that Samuel Sheppard believed was the real killer. His name was Richard Eberling, and he worked as an occasional handyman in the neighborhood where the Sheppards lived. He first came under suspicion in 1959, when he was arrested for larceny. As it turned out, Eberling stole various items from the houses where he worked, and he had in his possession some rings which had belonged to Marilyn Sheppard. While the handyman admitted to thievery, he claimed he stole the jewelry years after her death, from the house of her brother-in-law.

During the original trial, Eberling was dismissed as a suspect after allegedly passing a polygraph test with flying colors, but a modern evaluation claimed that the results had been misrepresented, and that they had been inconclusive, at best. The same thing applied to the modern DNA tests – they did not specifically implicate Eberling, but they also did not rule him out. Another uncertain aspect was the memorable trait provided by Sam Sheppard regarding his attacker – being bushy-haired. Richard Eberling was balding at the time of the crime; he certainly was not bushy-haired, but he was known to wear toupees so this, too, did not conclusively condemn or acquit him.

Decades later, Eberling was sentenced to life in jail for the murder of a different woman named Ethel May Durkin. During his incarceration, two people came forward, claiming that the former handyman had confessed to them in private to the murder of Marilyn Sheppard: one was a woman who used to look after Ethel May Durkin and the other was a fellow inmate. Richard Eberling died in prison in 1998, so no charges were ever brought against him.

Another, even more recent suspect, comes to us courtesy of retired FBI agent Bernard Conners, who pointed the finger at a former Air Force Major named James Call. After his own wife died, Call began committing robberies, and Conners believes that he burgled the Sheppard home, and attacked Marilyn when she caught him red-handed.

Ultimately, the jury in Samuel Sheppard’s wrongful imprisonment suit sided with the county. It seems that almost half a century later, many people were still not convinced of Sam Sheppard’s innocence. And that still goes on to this day. People write books, articles – some point the finger at Dr. Sheppard, others at Richard Eberling, and some believe the murderer may have been a third man. At this point in time, with almost everyone involved in the case dead, it’s looking highly unlikely that we will ever discover the whole truth.