Today’s protagonist was born as a Prince in a southern Indian kingdom, but he soon discarded his palace life to embrace the study of Buddhism. As a travelling Master, he journeyed to China, where he gained powerful disciples and founded Dhyana Buddhism, better known in China as Chan, and later in Japan as Zen.

He is also credited as the first Kung Fu Master at the Temple of Shaolin. He popularised meditation, introduced green tea to China, and had a curious second life as a popular Japanese doll.

Put the kettle on the stove, control your breathing, and sink into the life and legend of Bodhidharma, known as Da Mo in China and Daruma in Japan. Here is the life and legacy of the 28th Buddha:

The Prince of Pallava

Most of what we know about Bodhidharma is painted in the colours of legend; however, there is a historical account of his life written by the Chinese monk Daoxuan in the 7th Century AD.

Bodhidharma’s exact date of birth is not known. We do know that he was active throughout the first half of the 6th Century AD and was born in the South Indian Kingdom of Pallava, corresponding to the present-day States of Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, and Andhra Telangana. At birth he was called Bodhyottara, and he wasn’t exactly just another citizen of Pallava — he was a Royal Prince, the third and youngest son of King Simhavarman II.

The capital city of Pallava was a placed called Kanchi, and it was a prominent centre of Buddhist scholarship, giving birth to many masters of the Mahayana strand of Buddhism.

The King himself was interested in the Dharma, a term which indicates the words of the Buddha, the practice of his teaching, and the attainment of enlightenment. That is why he arranged for he and his sons to be trained by the famed master Prajnottara.

Prajnottara was the 27th in a lineage of masters and disciples that could be traced back directly to Siddhartha Gautama, known simply as the Buddha, the famous founder of the religion.

During the course of the training, the master noticed the spiritual potential and wisdom of the youngest prince, but he decided to wait before making of Bodhyottara his chosen disciple.

The time was finally ripe when the King died. While everyone was in mourning, Bodhyottara remained in a state of deep, constant meditation for seven consecutive days. After finally rising a full week later, he went to Prajnottara and requested to be accepted as his disciple.

Prajnottara took him under his wing and imparted all the necessary teachings to make of him a new master. Under the guidance of his mentor, Bodhyottara deepened his understanding of the Dharma, but also mastered Ayurvedic medicine, acupressure and martial arts.

When he eventually became bodhi or ‘awakened’, Prajnottara gave him his new name: Bodhidharma. He had now become the 28th in that unbroken lineage of realized Masters.

Buddhism in (about) 3 minutes

I expect that by now your water has boiled. As your green tea brews for the three minutes required for the perfect cup, let me give you a quick summary of the main tenets of Buddhism.

Buddhism is a religion based on the teachings of Siddhartha Gautama, born in the 5th century BC in modern-day Nepal. He was known by his title “the Buddha,” meaning “the awakened one,” after he experienced a profound realization about the nature of life, death, and existence.

The Buddha travelled and taught throughout his life, but he didn’t teach people what he had begun to understand when he became awakened. Instead, he taught people how to realize this awakening for themselves, which would arrive through their own direct experience, rather than beliefs and dogmas. He wasn’t offering an answer; he was teaching his pupils how to ask the right question.

By the 3rd century BC, Buddhism had become state religion in India, and from there it spread throughout the rest of Asia. Today, the number of Buddhists is estimated to be about 350 million, which makes Buddhism the fourth largest religion in the world … although it is questioned whether it should be considered a religion at all. Buddhism is non-theistic at its core and coexists well with other established religions. As a result, some scholars choose to consider it as more of a philosophical doctrine than an explicit religion.

Nomenclature aside, the detail that sets Buddhism apart from other religions is the lack of dogmatic truths to be memorized and believed. The Buddha taught his followers how to realize truth for yourself, so its focus is on practice, rather than belief.

In spite of this emphasis on free inquiry, Buddhism does provide some explicit beliefs, known as the Four Noble Truths:

The truth of suffering, or “dukkha”

The truth of the cause of suffering, or “samudaya”

The truth of the end of suffering, or “nirhodha”

The truth of the path that frees us from suffering, or “magga”

Practitioners are encouraged to explore the teachings that shape these truths and test them against their own experience.

And while these truths have been consistent across time, about 2,000 years ago Buddhism divided into two major schools: Theravada and Mahayana, which I mentioned earlier, and is the school to which Bodhidharma adhered to.

The two schools differ in their understanding of the concept of “anatta.”

Buddhists believe there is no “self” in the sense of a permanent, integral, autonomous being within an individual existence.

The Theravada school considers anatta to mean that an individual’s ego or personality is a delusion. Once freed of this delusion, the individual can enjoy the blissful state of Nirvana.

Mahayana Buddhism goes further, considering all conscious phenomena as void of intrinsic identity. They craft identity only in relation to other phenomena. The implication is that there is neither reality nor unreality, only relativity. This teaching is called “shunyata,” or “emptiness.”

Another defining aspect of Mahayana is the ‘Buddha Nature’. This is a fundamental nature accessible to all beings, which offers the potential to reach the awakening, or enlightenment, through practice. According to 13th Century Japanese Monk Eihei Dogen, enlightenment is intrinsic to the Buddha nature. Therefore, all beings are already enlightened, but we need to clarify the nature of our existence to experience the awakening that was always there.

And with that, it’s time to sip your tea, while I continue with our story.

The Emperor and the General

After completing his training, Bodhidharma was instructed by Prajnottara to travel to China and impart the teachings of Mahayana.

Upon arriving, Bodhidharma felt that people were too focused on the conventions of Buddhism, rather than its essence. They were too preoccupied with building temples and chanting, rather than looking into their own minds for spiritual growth.

Some time after arriving, Bodhidharma was invited to a monastery to deliver a lesson to a large number of students, but the Master just sat in front of them, meditating. Hours passed by, with Bodhidharma ever undisturbed by the whispers and murmurs of an impatient assembly.

Eventually, he just silently stood up and walked away. Had he gone crazy? Was there a mystical meaning behind his silence? His simple intent was to shock them, to get students to consider abandoning the pursuit of the exterior trappings of Buddhism. To focus on a journey toward the realization of ‘shunyata’, emptiness, through the means of meditation: Dhyana in Sanskrit, or Chan in Chinese.

The news of these teaching methods reached Emperor Wu of Southern China, an avid practitioner of Mahayana Buddhism. He supported the monastic orders generously, built many Temples, promoted vegetarianism and banned the sacrifice of animals and capital punishment.

Believing he had earned an audience with a wise master like Bodhidharma, Wu summoned the Indian master to his court and recounted his own great deeds. He then asked,

“Having done all these, how much merit do I have?”.

Bodhidharma replied:

“None”.

The Emperor was taken aback by this answer and pressed on:

“What is the first principle of the holy teachings?”

Bodhidharma replied:

“Vast emptiness, nothing holy.”

Bewildered, the Emperor continued:

“Who is standing before me then?”

Bodhidharma replied:

“I don’t know”.

This conversation may have never happened, but it is one of the first recorded Koans — paradoxical anecdotes or riddles, used in Zen Buddhism to invite deep introspection.

The meaning of this koan is to undermine the idea of identity and holiness. The Emperor is portrayed as performing good deeds, but these are just meant to reinforce his ego, to use a modern concept. A king who clings to his ego will never find the bliss of Nirvana, or the freedom of liberation.

For the second question of the Emperor, the Master’s response points out that there is nothing to cling to as ‘holy’. Everything is inherently holy. Trying to differentiate between ‘holy’ and ‘unholy’ is quintessentially unholy.

And the third response shatters again the concept of ego, this time for Bodhidharma himself. As his thoughts are passing through him like water in a river, nothing stays as the true Bodhidharma. Self-image is only a mirage.

The story goes that Wu did not fully comprehend Bodhidharma’s teachings, and continued on without a true sense of understanding. Only later did he realise the depth of Bodhidharma’s message, and he lamented:

‘Alas! I saw him without seeing him; I met him without meeting him; I encountered him without encountering him; Now, as before, I regret this deeply!’

Bodhidharma continued his journey to the city of Nanjing, on the Yangtse River. There, he came across a large crowd rallied around a famous Buddhist monk, Shen Guang, who happened to be a former warrior, a General, and one who had not entirely lost his taste for aggression.

Bodhidharma sat down to listen to Shen Guang, but his constant nodding irritated the ex-soldier. Eventually, Shen Guang raised his rosary of heavy beads and hit Bodhidharma in the face, out of frustration. The blow knocked out two of Bodhidharma’s teeth … but the Master just smiled and walked away.

Shen Guang was intrigued by this reaction and immediately started following the Indian master. When he reached the banks of the Yangtse River, he was startled by the sight of Bodhidharma gently gliding through the water, standing on a single reed, as if completely weightless.

Well, he could do that, too, couldn’t he? Seeing an old lady sitting with a bundle of reeds on the bank, Shen Guang snatched two reeds off her, tossed them on the river and jumped on them. Naturally, he drowned.

Well, almost, as the old lady kind enough to pull him out of the water.

As Shen Guang’s anger boiled over, he realised that the man he was following may have been trying to teach him a lesson, literally. He had acted out of aggression and mindlessness, without considering for a second that Bodhidharma may have been able to sail on a single reed by virtue of his mindfulness. Shen Guang had been dragged down into the water by the weight of his physical body, as well as the weight of his own self.

The former General had run after Bodhidharma out of curiosity, but now all he wanted was to really know the man. He wished to become his disciple.

The Masters of Shaolin

Bodhidharma continued his journey, and around the year 527 AD he finally reached his destination: The Temple of Shaolin, one of the major centres of Buddhism in China, founded by another Indian master, Buddhab hadra, in 495 AD.

The Shaolin monks had heard of his approach and were gathered to meet him. When they invited Bodhidharma to come stay at the temple, though, he did not reply. Instead, he walked to a nearby cave on a mountain behind Shaolin, sat down, and began meditating.

Here, the stories tell us that the Indian master sat facing a cave wall and meditated for nine consecutive years. According to one story, his concentration was so intense that the image of his body was engraved into the stone of the wall before him.

According to another account, his stillness was so unbroken that all four limbs eventually withered and fell off.

Other legends claim that Bodhidharma was unable to stay fully awake during his nine years of meditation. Out of frustration, he pulled out a knife and proceeded to cut off his eyelids. As the two scraps of skin fell on the ground, a tea leaf sprouted on the very spot, the first to ever grow in China.

But for now, I am going to stick to an account in which the Master’s body remained intact inside the cave. In the meanwhile, Shen Guang had caught up with him. Unable to get a word out of Bodhidharma, the Chinese monk decided to stay outside the cave and stand guard.

Every so often, both Shen Guang and the Shaolin monks would try and interact with Bodhidharma, but no one ever received a reaction.

Finally, after nine years had passed, the puzzled monks decided that they had to do something for the enigmatic Master. So, they built a special room inside the Temple, just for him. The Shaolin monks invited Bodhidharma to come and stay in the room, to which he did not immediately respond. Instead, he stood up, walked down to the room, sat down, and immediately began meditating. For another four years!

Shen Guang had been standing guard now for a total of 13 winters. All his requests to be taught by Bodhidharma had been ignored. In a fit of frustration, Shen Guang picked a large block of snow and ice and hurled it into the Master’s room. This massive snowball had the intended effect of awaking Bodhidharma from his meditation. Shen Guang demanded to know, once again, when he would teach him. The reply he received?

‘When red snow will fall from the sky’

Something inside Shen Guang snapped and he knew immediately what to do. As a former warrior, he always carried a sword with him. He raised it high above his head and swung it downwards in a fast, powerful, cutting motion.

He had just cut off his own left arm.

Shen Guang grabbed his severed limb, raised it above his head and whirled it around. The blood still gushing from the left arm froze in mid-air and floated to the ground like red snow.

Seeing this act of self-sacrifice, Bodhidharma agreed to teach Shen Guang. Their subsequent conversation became another founding Koan of Zen.

Shen Guang beseeched the Master:

“My mind has no peace yet! I beg you, O Master, please put it to rest!”

Bodhidharma said

“Bring your mind here and I will pacify it”

Shen Guang searched for a while, then responded:

“I have searched for my mind, and I cannot take hold of it.”

Then Bodhidharma declared, “Now your mind is pacified.”

The next lesson from Bodhidharma would require four more years of Shen Guang’s life. Over that span, Bodhidharma asked him to live on top of Drum Mountain, in front of the Shaolin Temple. At the beginning of each year, the Master would dig up a well, to provide for all of Shen Guang’s needs. Each year, the water from the Master’s wells had a different taste: first bitter, then spicy, next: sour and finally: sweet.

At this point, Shen Guang realized that the four wells represented his life. Like the wells, his life would sometimes be bitter, sometimes sour, sometimes spicy and sometimes sweet.

Each of these phases in his life was equally beautiful and necessary, just as each of the four seasons of the year is beautiful and necessary in its own way. Bodhidharma had imparted this lesson almost without using any words, a type of “action language” that is fundamental to Chan, or Zen, Buddhism.

After this final ordeal and realization, Shen Guang was given the name Hui Ke by his master, and he became the abbot of Shaolin after Bodhidharma. To pay respect for the sacrifice which Hui Ke made, disciples and monks of the Shaolin Temple greet each other using only their right hand.

Zen and the Martial Arts

As I mentioned earlier, most of Bodhidharma’s life has been mystified by legend. But assuming what you heard is all fact, you may be wondering: While Shen Guang was barely surviving on water at the top of Drum Mountain, what was Bodhidharma up to?

We can assume it was during this four-year period that he shared his teachings with the Shaolin monks. According to some traditional accounts, he may have taught them how to fight. The Chinese martial arts, collectively known in the West as Kung Fu, may have been first introduced in the Country by an Indian wandering monk.

Could this be true?

Well, as a Royal Prince, the young Bodhidharma may have been already skilled the traditional Indian martial arts, such as Kalaripaiattu. Moreover, he received additional training from his Buddhist master Prajnottara. And some artwork at the Shaolin depicts a dark-skinned monk training lighter skinned students in a variety of hand-to-hand techniques.

However, the predominant point of view among current Zen scholars is that the claim that Bodhidharma invented Kung Fu is wildly exaggerated. For one thing, the first codified Chinese martial art, Jiao-di, pre-dates the Indian master by at least 30 centuries.

And while there is a record of Bodhidharma teaching some physical exercises to the monks, these are not necessarily related to combat. The exercises known as the “18 hands of Lohan” were intended to build up the monks’ Qi, or vital energy, to improve their general health and nourish their brains – a necessary step to attain awakening.

Some scholars may argue that a more realistic interpretation of Bodhidharma’s time at Shaolin is that he perfected and taught his new branch of Buddhism, Chan or Zen.

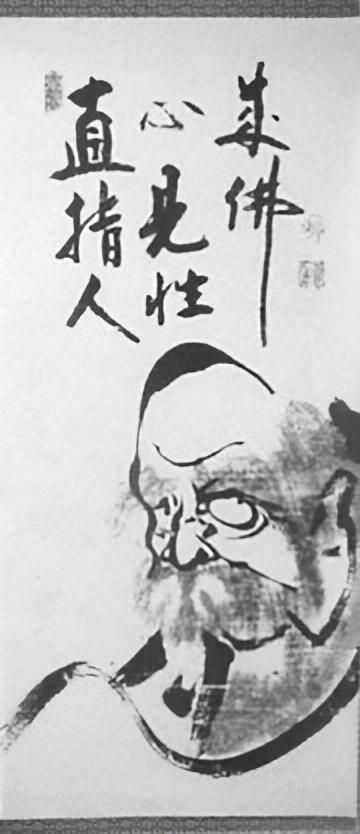

Now I guess it’s time for me to explain what Zen Buddhism is about. Bodhidharma himself defined Zen as:

“A special transmission outside the scriptures;

No dependence on words and letters;

Direct pointing to the mind of man;

Seeing into one’s nature and attaining Buddhahood.”

In other words, Zen requires a face-to-face transmission of Buddhist precepts, from teacher to student, outside the written tradition. And to do that, you need a proper certified Zen teacher, which I am not.

I can only add that Zen is not an intellectual discipline you can learn from books, or a video. Instead, it’s a practice of studying the mind and seeing into one’s nature. According to Bodhidharma, the main tool of this is the practice of meditation, best known from its Japanese name: zazen.

Beginners approaching zazen are taught to work with their breath to learn concentration. After a few months, your ability to concentrate may have ripened. As you progress, you may understand that the true goal of zazen … is that there should not be any goal, nor expectation to a particular meditation session. Practitioners should learn to ‘just sit’ in meditation – shikantaza – while learning a lot about themselves along the way.

Daruma

Bodhidharma’s lofty teaching in Shaolin and China had won him a few disciples, but also some powerful enemies, and we are told that he was eventually poisoned by two rivals. Allegedly, the sage survived both attempts.

Eventually, during the third attempt, Bodhidharma accepted to take the poison and died at the reported age of 150.

But was death the end? Three years after his death, a Chinese diplomat named Sòng Yún was returning to China from a trip to the West when he met none other than Bodhidharma. He was on his way back to India, walking barefoot and carrying one shoe in his hand.

When the diplomat finally got home, and told this story, the master’s grave was opened. Inside, it was empty, except for one shoe.

Another version of Bodhidharma’s last years on Earth tells of how the master left China for Japan, where he, disguised as a beggar, met with Prince Shōtoku Taishi, celebrated as the first great patron of Buddhism in Japan.

While Bodhidharma’s travels to Japan are strongly disputed, it is a fact that his teachings did gain great popularity there. The master became known as Daruma, and his appearance and story inspired one of the most popular symbols of Japanese folklore, the Daruma doll, popular with locals and tourists alike.

If you have visited Japan, you may have taken home one of these, wondering what’s the reason behind the round shape and the blank, white eyes.

The shape of these dolls reflects the nine years that Daruma spent meditating in the cave near Shaolin. Remember? His immobility was such that all his limbs had fallen off.

The wide-opened eyes of the doll remind us of how the master had cut off his eyelids to remain awake during zazen. The dolls are normally made without their pupils, it is up to their owners to draw them once their wishes are fulfilled.

Over time, the doll took a life of its own, collecting attributes further and further removed from the original inspiration. For example, it was dressed in red, a colour associated with measles and smallpox, and became a talisman to protect children against these diseases.

In a surprising twist, artists of the Edo era (1603 to 1868) even morphed these dolls into phallic symbols. The sexual attributes were then shifted onto the sage himself, who became the object of parody-filled illustrations in which he leers at prostitutes or courtesans. What a strange, worldly tribute to the man who once said

“To have a body is to suffer”

I hope you learned something new from today’s video … and I hope that what you learned is that you can’t really learn anything by reading a book or watching a video.

Sources – further reading

Biographies of Bodhidharma

https://www.usashaolintemple.com/chanbuddhism-history/

https://www.wayofbodhi.org/bodhidharma-lifestory/

https://www.britannica.com/biographyi/Bodhidharma

Zen

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Buddhism/Pure-Land

https://www.wayofbodhi.org/bodhidharma-teachings/

https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b04sxv29

https://www.learnreligions.com/introduction-to-zen-buddhism-449933

Martial arts

https://www.wayofbodhi.org/bodhidharma-and-martial-arts/

Buddhism

https://docs.google.com/document/d/1fNa4nFD6_RsN9IZv5Q9Y0tZfDbvSUy3CrfubXlugF0I

https://www.learnreligions.com/what-is-the-buddha-dharma-449710

Daruma in art

https://www.onmarkproductions.com/html/daruma.shtml

Daruma the doll

https://darumasan.blogspot.com/2009/07/red-and-smallpox-essay.html

https://www.tokyoweekender.com/2017/11/dark-history-daruma-doll/