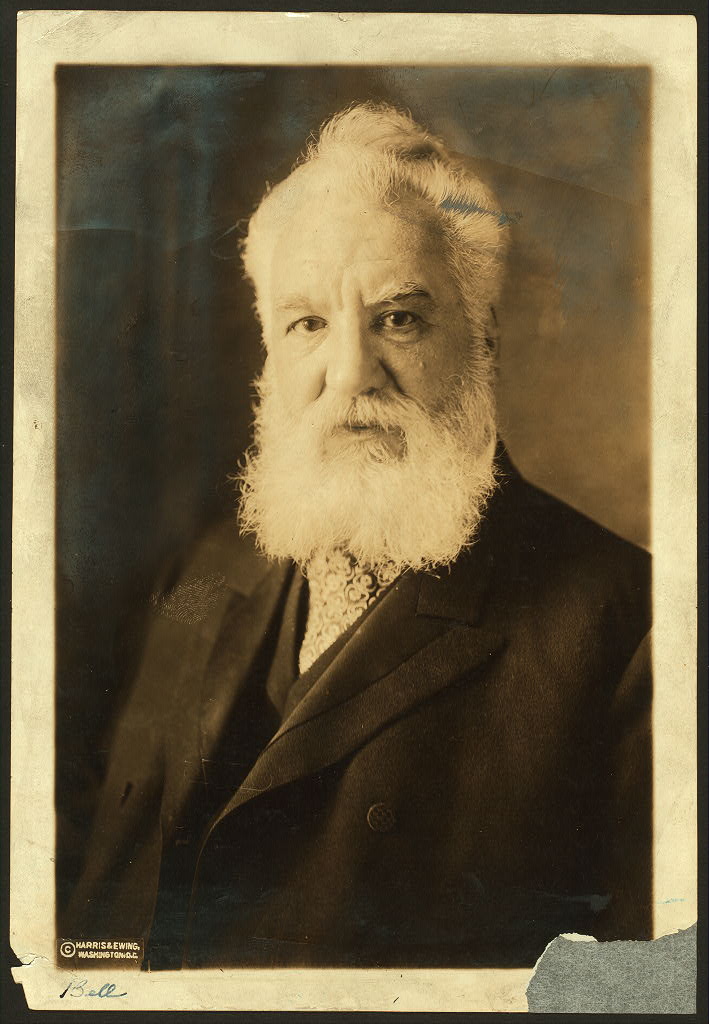

Today we look at the life of a man who is regarded as being one of history’s greatest inventors – Alexander Graham Bell. Inexorably, he is linked with the telephone, although we will see that he worked on everything from wireless technology and sound recorders to planes, boats, and even a metal detector.

His career was not without controversy, though. He had to face almost six hundred lawsuits in his lifetime. Was he truly the inventor of the telephone or just someone who stole ideas and had better lawyers? Was he a champion of deaf people or did his efforts do more harm than good? Neither question can honestly be answered with certainty so those might be decisions that you’ll have to make for yourself after you have finished reading this article.

Early Life

Alexander Bell was born on March 3, 1847, in Edinburgh, Scotland, to Alexander Melville Bell and Eliza Grace Symonds. He had two older brothers, Melville and Edward, who both died of tuberculosis when Bell was a young adult.

Originally, he was simply named Alexander, but the young Bell wanted a middle name like his two older brothers. His father relented and, on his 11th birthday, gifted him the middle name Graham after Alexander Graham, one of his father’s former students and family friend.

From a young age, Alexander Graham Bell showed an interest in studying speech and phonetics. This was not very surprising seeing as his father and grandfather were both phoneticians. His father was a professor who wrote several seminal works on the subject and developed a phonetic alphabet called Visible Speech. There was also a personal motivation for Bell as his mother (and, later, his wife) were both deaf.

Allegedly, Bell’s first invention came at the tender age of 12. He was playing with a friend whose family owned a flour mill and noticed how long it took to husk the grain. He then built a machine which used rotating paddles and nail brushes to speed along the laborious process.

Another notable episode in the development of young Bell’s scientific interest was when his father took him and his brothers to see a talking automaton based on the Mechanical Turk which had been lost in a fire. The Turk, built a hundred years prior by Hungarian inventor Wolfgang von Kempelen, was a sensation in its day. Purportedly, it was a mechanical device that could play chess on its own against human opponents. Notable statesmen such as Ben Franklin and Napoleon, both keen chess players, were bested by the machine.

Although the Turk was an amazing creation capable of impressive movements, one thing it could not do was play chess. In that regard, the Turk was a hoax for inside the machine was room for a human chess master who actually controlled the automaton’s moves.

Moving to Canada and Continued Research

The death of Bell’s brothers came in short order, just three years apart. After Bell himself and his father also suffered health scares, the family decided to leave the big city and move to a quiet place in Canada because it had a healthier climate. They settled on Brantford, Ontario, where the Bell Homestead still stands as a national historic site and museum. Bell set up a workshop to continue his studies into speech and sound, but also began traveling to Massachusetts and Connecticut to teach his father’s Visible Speech System to schools for the deaf.

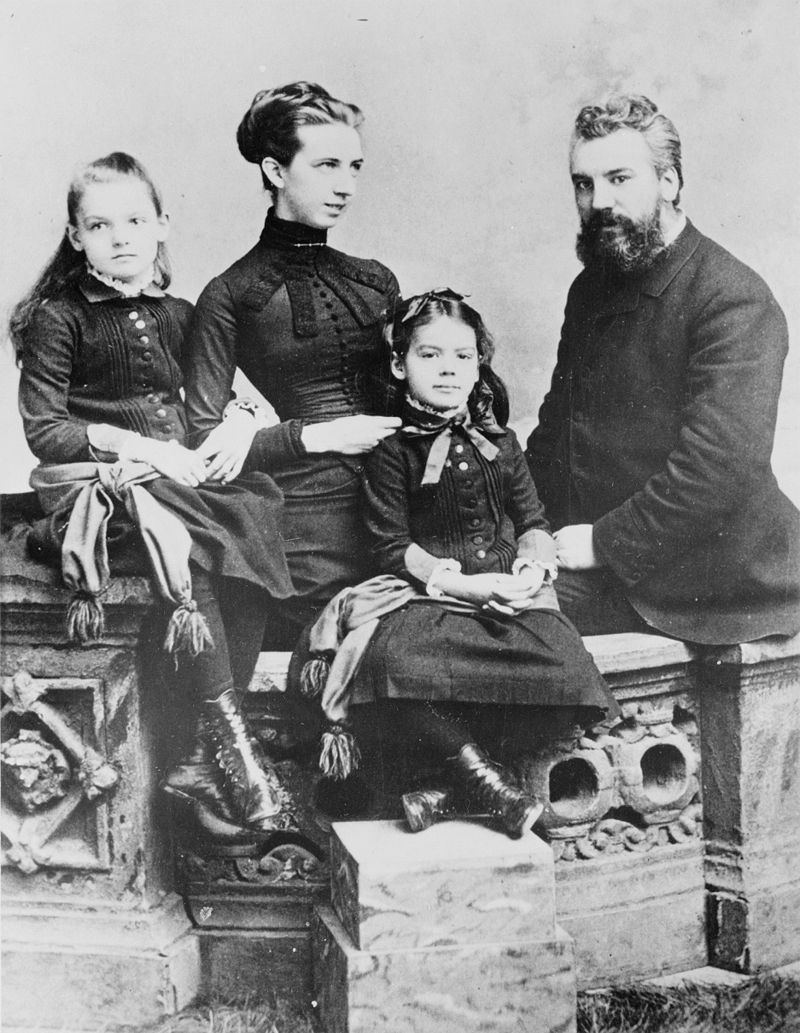

He worked as a teacher for the next few years, first as Boston University and then at his own private practice. During this time, he met 15-year-old pupil Mabel Hubbard and fell in love with her. Her father, Gardiner Greene Hubbard, was a wealthy, influential man in Massachusetts who funded some of Bell’s research. He and his partner, Thomas Sanders (who also had a deaf child tutored by Bell), wanted to secure patents related to telegraph technology so they financed Bell’s work perfecting the harmonic telegraph. Such a system allowed multiple messages to be transmitted simultaneously over a single telegraph wire, but it was this research that led to Bell inventing the telephone.

First Words

On March 10, 1876, Alexander Graham Bell uttered the first words into a telephone. They were “Mr. Watson, come here – I want to see you”. His assistant walked into his office and the two swapped places, with Bell now listening to Watson read a few passages from a book. Bell noted that he could definitely hear loud, articulate sounds, but that they were “indistinct and muffled”.

Watson’s journal added a bit of contention to the proceedings. First off, he noted the famous sentence to be “Mr. Watson, come here, I want you”, not “I want to see you”. He also claimed that these words were not merely a test of the telephone, but rather a cry for help as when he entered Bell’s office, he discovered that the inventor had accidentally spilled battery acid on his clothes. This story was later debunked by Watson’s own great-granddaughter as a fabulation of her forefather he made up decades after the fact.

Three days prior, Bell was awarded patent No. 174,465 for “improvement in telegraphy”, which would become one of the most valuable (and most controversial) patents in American history. Gardiner Greene Hubbard set up Bell Telephone as a joint stock company to look after their interests and split 5,000 shares of the company between four people: him, Bell, Thomas Watson, and Thomas Sanders.

On a personal level, Alexander Graham Bell was soon-to-be a rich man as he owned around 1,500 shares of the company. Finally, Gardiner Hubbard consented to him marrying his daughter Mabel, the deaf pupil that Bell taught and fell in love with a few years back. On July 11, 1877, just a few days after the Bell Telephone Company was founded, Mabel and Alexander (or Alec, as she called him) tied the knot. To show his love and trust, Bell gifted Mabel all but ten shares in his company as a wedding present.

Who Invented the Telephone?

Now we arrive at the most contentious and controversial aspect of Bell’s legacy. Did he really invent the telephone or did he steal his idea and make a fortune off others?

The answer is a resounding “We’re not sure”. The topic has been fiercely debated for almost 150 years and has been the subject of books and hundreds of lawsuits. Everybody has an opinion on it, but it is far from a settled matter.

When it comes to complicated inventions like the telephone, they are often the result of the work of multiple people. Oftentimes, credit ends up going to the person who makes the most practical or best working version rather than the ones who originate it. History also tends to have a short attention span and attributes the work of many to one for the sake of brevity. It is certainly not fair, but it is what tends to happen.

Antonio Meucci

Apart from Bell, there were other inventors who had substantial claims to the telephone. Italian Antonio Meucci built a device described as an “electromagnetic telephone” decades before Bell. He kept on improving it, but never found the money needed to finance his invention. In 1871, he didn’t even have the funding necessary to take out a patent for his “teletrofono”, as he dubbed it. Instead, he filed a caveat – an official notice that a patent will be filed at a later date. It was much cheaper, but also needed to be renewed annually, something which he stopped doing in 1874. He tried to obtain funding from Western Union, but not only did they turn him down, they later claimed to have lost the proprietary materials he sent them.

Meucci and Bell went to court and, at first, things seemed to go in the Italian inventor’s favor. The Supreme Court agreed to hear the case and fraud charges were filed against Bell. However, Meucci died in 1889 and his case died with him.

Italy, of course, always considered Antonio Meucci to be the rightful inventor of the telephone, but in 2002 so did the United States House of Representatives. They passed a resolution which honored Meucci’s work and specified that if he had continued to pay the fee for his caveat, no patent could have been issued to Bell.

A few days later, to show support for “their guy”, the Canadian Parliament passed a motion, reaffirming Alexander Graham Bell as the inventor of the telephone.

Elisha Gray

The story of Elisha Gray is much better known to the public. It was a race to the patent office between him and Bell as they created their versions of the telephone around the same time. The Scottish inventor beat Gray by a few hours and, therefore, secured his spot in the history books while Elisha Gray became a footnote.

Gray, like Bell, was working on the harmonic telegraph with funding from Western Union. He developed a device that could transmit musical tones using vibrating reeds in 1874, but didn’t follow through on it immediately. Over a year later, he finally drew a diagram of his device and had his lawyer file a caveat with the patent office on February 14, 1876. Of course, by then it was too late, as Bell’s lawyer had already submitted his patent to the office.

A legal battle ensued. There were even accusations that Bell stole ideas from Gray, particularly his design for a liquid transmitter. The most egregious claim came courtesy of patent examiner Zenas Fisk Wilber who confessed that he was bribed to show Gray’s caveat to Bell and his lawyer, Marcellus Bailey, which he did because he was heavily in debt to Bailey. Bell, obviously, denied all charges of wrongdoing and the fact that Wilber was an alcoholic and had given conflicting affidavits sunk his credibility.

In the end, the courts sided with Bell and subsequently upheld his patent in hundreds of other lawsuits.

Success of the Telephone

Another challenger to Bell and his telephone was Western Union which, at the time, was the largest communications company in the world. In what is widely regarded as one of the worst business decisions of all time, Western Union turned down the opportunity to buy the patent for the telephone for only $100,000 when the technology was in its infancy. Company president William Orton balked at the idea, seeing the new device as just a “toy”. He considered the telephone impractical and believed that no one would prefer it over the telegraph.

He was wrong, as you might imagine. The telephone took off almost immediately and, just two years later, his company valued the patent at $25 million. Western Union tried to get into the game and tasked Thomas Edison to build an improved device that they could patent. The two companies went to court and Western Union lost…badly. In the end, it surrendered all telephone-related patents and agreed to pull out of the business entirely in exchange for a few minor concessions.

It was at this time that Thomas Edison provided his own contribution to the telephone, one which is still around today long after the patents expired and the technology became obsolete. He popularized the greeting “Hello”. The word existed before then, but it was typically used as an exclamation as in “Hello, what’s going on here?”

If it were up to Alexander Graham Bell, even today we would be answering our phones by going “Ahoy”.

The Volta Bureau

In 1880, Bell used his money to establish the Volta Laboratory in Washington, D.C., and continue research into sound technologies. In 1887, he also founded and funded the Volta Bureau whose goal was to help deaf people. It later merged with a different deaf-related organization of which Bell was also president and today it is known as the Alexander Graham Bell Association for the Deaf and Hard of Hearing or, simply, the AG Bell. The original building is still around, serving as headquarters for the institution, and is listed as a national historic landmark.

Given how much Bell revolutionized oral communication, it is a shame we have no idea what he actually sounded like. Well, not so fast. It was thought that no recordings of him survived, but that changed in 2013. The Smithsonian Institution found an old wax-and-cardboard record from Volta Laboratory and researchers were able to recover the audio. It is over four-and-a-half minutes of Bell reading various numbers and dollar figures. Fittingly, it ends with the words “hear my voice…Alexander Graham Bell”.

Helper or Hinderer?

With all the work he did with deaf people, you would think that Bell would be regarded as a hero in this community, but, actually, he is quite a controversial figure. He held some strong views about how the condition should be approached which involved keeping deaf people apart from one another and completely eliminating sign language.

Bell considered the only proper way to teach deaf people was through oralism – communication through the use of speech and lip-reading. He regarded sign language as a foreign language, one which had no place in the United States. He tried to have it removed from schools.

Moreover, he wrote a paper called “Upon the Formation of a Deaf Variety of the Human Race” which warned of an upcoming “calamity” involving the creation of a “deaf race”. He believed that deaf people should not socialize with each other because socialization leads to marriage which leads to children who will also be deaf.

This all fell in line with his advocacy of eugenics. He believed the practice could be used to improve human breeding, although he never went as far as others to suggest that the government should impose any kind of controls on reproduction. Instead, he wanted the elements that promoted deaf intermarriages to be identified and eliminated.

Just like the telephone, Bell’s work with the deaf left behind a tainted, vexatious legacy.

The President Is Shot

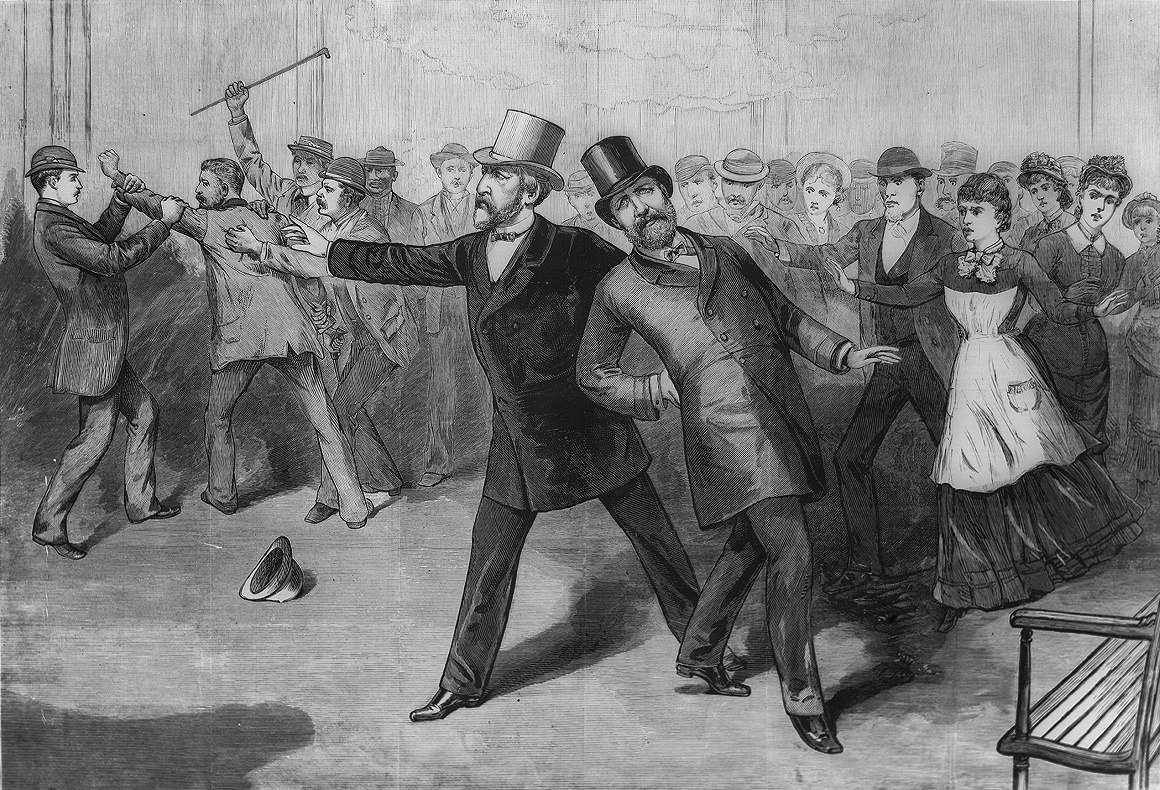

On July 2, 1881, United States President James Garfield was getting ready to leave Washington, D.C., for his summer vacation. At the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station, he was approached by a disgruntled supporter and office seeker who shot at him with a Bull Dog revolver from point-blank range. While one bullet only grazed Garfield, the other hit him in the back and got lodged inside his body.

The president died 80 days later after his doctors proved unable to locate and extract the bullet, despite some assistance from Alexander Graham Bell.

Charles Guiteau

The murderer was Charles J. Guiteau, a man who concomitantly thought he was doing the Republican Party a favor by getting rid of Garfield and who also believed that he was being commanded by God. Modern medical professionals have diagnosed Guiteau of likely being a narcissistic schizophrenic with delusions of grandeur, but even in his own time talk of his mental health was a hot topic among alienists. They were very keen to examine his brain which is still on display in the main hall of the Mütter Museum in Philadelphia.

Image suggestion: Guiteau’s brain, Mutter Museum

Neurologist Edward Charles Spitzka testified at Guiteau’s trial and said that he suffered from “moral insanity”, something we would likely call sociopathy today. Coincidentally, the doctor’s son, Edward Anthony Spitzka, followed in his father’s footsteps and, 20 years later, would perform the autopsy of the next presidential assassin, Leon Czolgosz, who killed William McKinley in 1901.

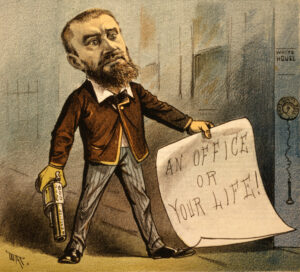

During his life, Guiteau jumped on many bandwagons. His latest was a Republican faction called the Stalwarts. During the 1880 election, he wrote a rambling speech in support of Garfield which he was allowed to deliver once in front of a small crowd in New York City. It was less than nothing but, in Guiteau’s mind, his speech was crucial to helping Garfield win the election. Afterwards, Guiteau started roaming the halls of the White House and State Department, badgering anyone who would listen about his “deserved” reward. He wanted a diplomatic post to Paris or, maybe, Vienna.

Of course, nobody took him seriously and, eventually, Secretary of State James Blaine told him, in no uncertain terms, to go away and never bother him again. This launched Guiteau on his downward spiral of madness. In his mind, he needed to get rid of Blaine which, obviously, could only have been achieved by killing the president. His delusion was so great that, during his trial, Guiteau believed he would be acquitted because the American people would rise up and demand his release. When this didn’t happen and he was convicted, he was still certain that new United States President Chester A. Arthur would pardon him.

A Medical Conundrum

Going back to Garfield, his injuries and treatment are still discussed in medical circles today, almost 140 years later. Specifically, people talk about how the president was as much a victim of medical incompetence as he was of an assassination attempt. Perhaps one of the sanest things that Guiteau said during his trial was that “the doctors killed Garfield, I just shot him”.

As it was later revealed, the mystery bullet lodged itself in the president’s soft tissue. Nowadays, finding it would be trivial and the patient would be on the mend and out of the hospital in just a few days. However, even in his time, Garfield would have had a decent shot at survival with a more adroit medical staff.

A lot of the blame rests on the man who self-appointed himself as White House physician. He was Dr. Doctor Willard Bliss (and yes, his first name really was Doctor). By that time, British surgeon Joseph Lister was already telling physicians to wash their hands and sterilize equipment to prevent infections, but the idea had not been accepted across the pond yet. Therefore, Bliss and over a dozen other doctors routinely stuck their unclean fingers inside Garfield’s wound, trying to locate the bullet. This led to infections and, eventually, sepsis. Moreover, the president lost almost 80 pounds during his hospitalization due to a diet prescribed by Bliss which was very non-nutritious and heavy on morphine.

Bell Offers Help

When Bell heard that the president was shot and doctors couldn’t find the bullet, he went to work on a device that could detect hidden metal. He called it an “induction balance” device and it was actually based on an earlier invention by French electrical engineer Gustave Trouvé. Bell tested it on Civil War veterans who had bullets still lodged in their bodies and found that his device was only sometimes successful.

Bell’s invention had a large battery with a condenser, a wooden controller which was passed over the patient’s body, and a telephone receiver which he kept to his ear to listen for the sound of metal.

Bell first tried to use his “induction balance” machine on Garfield in late July. He assembled the device on-site, but all he heard coming out of the receiver was a strange sputtering noise. He failed to locate the bullet, but later concluded that, in his haste, he made mistakes while constructing the device. Bell returned on August 1 and tried his test again, but still failed to pinpoint the location of the bullet. He went back to the drawing board, but never got a chance to try the metal detector again. President Garfield died on September 19 of sepsis and emaciation.

Now, there is still plenty of discussion regarding the reason why Bell’s device failed. The most common story in circulation puts the blame on interference from the president’s mattress which was made using steel wires. However, in a report, Bell expressed his belief that the bullet was too deep inside the body to be picked up by his metal detector. Dr. Doctor has also been accused of only allowing Bell to check the president’s right side because he was convinced that was where the bullet was located. An autopsy later proved him wrong.

Continued Innovation

The telephone brought Bell fame and fortune and working with the deaf was his true passion, but he was a scientist of many interests who had dozens of patents in other areas. Alongside Charles Sumner Tainter, he created an improved version of the phonograph dubbed the “Graphophone”. They set up a new business for this invention called the Volta Graphophone Company. It later merged with another company which evolved into what is known today as Columbia Records.

Even more impressive, the two created a primitive version of a wireless telephone Bell called a “photophone”. He used it to transmit an audio message to Tainter over 650 feet away. In an interview, Bell called this his “greatest achievement”, although it wouldn’t be until the arrival of fiber optics that such technology would become truly useful.

Bell also served as second president of the National Geographic Society and helped turn it into one of the largest non-profit scientific organizations in the world. He was not, as is sometimes stated, among the original 33 founders, although his father-in-law, Gardiner Greene Hubbard, was.

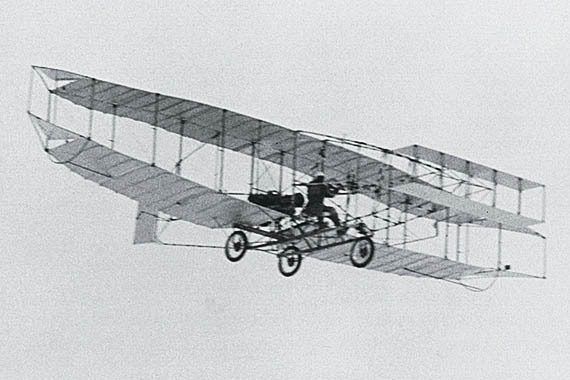

Perhaps most surprising (and most obscure) of all was his work in aeronautics. He founded the Aerial Experiment Association with like-minded individuals such as aviators Glenn Curtiss and Thomas Selfridge. Together, they designed and built the Silver Dart which, in 1909, made the first powered flight in Canada.

From planes, Bell moved on to boats. With engineer Casey Baldwin, he built a hydrofoil boat dubbed the HD-4. On September 9, 1919, it set the new boat speed record at 61.58 knots. This and the Silver Dart flight both occurred at the Bras d’Or Lake in Nova Scotia, near Bell’s estate of Beinn Bhreagh where he spent the last three decades of his life.

As you can see, Bell’s career was full of innovation long after the telephone came into being. The HD-4 turned out to be his last taste of greatness as Bell died a few years later, in 1922. He left behind a legacy that is sure to stir up mixed emotions and elicit differing reactions from people.