There has been spirited debate among historians over which of the 46 Presidents of the United States ranks as “the best.” There has also been a spirited, though somewhat more subdued, debate over which of them was “the worst.” And boy, have there been some bad ones, from James Buchanan, who essentially sat on his hands and watched as the nation tore itself apart and triggered the Civil War, to Warren G. Harding, who famously presided over one of the most corrupt administrations in history. But no debate about “worst Presidents of all time” would be complete without mentioning John Tyler, the 10th President.

Tyler was never supposed to be President, he assumed the office following the sudden death of his predecessor, the first time that had happened in American history. It was just the first of a string of unprecedented events that would shape American politics for a generation. Among other things, Tyler successfully derailed the legislative agenda of his own party, causing them to expel him from their ranks. His obstinance irritated almost everyone in Washington, to the point that he had few friends and entirely too many enemies. Even his most important achievement during his Presidency, adding Texas to the Union, ultimately triggered a war that caused the deaths of tens of thousands, and set the stage for an even more destructive war a decade later.

As if that weren’t bad enough, John Tyler managed to ruin his reputation even further at the end of his life, when he advocated for secession and was elected to the Confederate Congress, causing many to view him as a traitor. When he died, he was accorded almost none of the honors usually given to a former president, and the historical outlook on his life and career has hardly been rehabilitated by the passage of time.

Virginia Gentleman

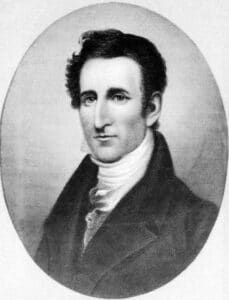

John Tyler was born on March 29, 1790, in the Tidewater region of southeastern Virginia. The Tylers were one of the wealthiest families in the state, tracing their roots back to colonial times, and had a long history of public service. Tyler’s father, John Sr, known as Judge Tyler, was no exception, enjoying a distinguished political career that included a close friendship with Thomas Jefferson and election as Governor of Virginia in 1808.

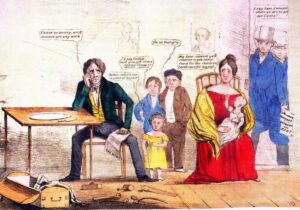

From the start, John Tyler was raised to become everything his father was: a lawyer, a future politician, and above all, a perfect Southern gentleman, concerned with his standing in society and his “honor” at all times. Like many boys, John loved his father and wanted to make him proud, so he studied hard, graduating from the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg in 1807, when he was 17. He passed the bar and became a lawyer at 19, technically two years too young to sit the exam, but it seems the examiner simply hadn’t bothered to find out how old he was. He began practicing as a lawyer in Richmond, and he was good at it, but his real passion was politics. In fact, the only reason he became a lawyer in the first place was because it was seen as a necessary prerequisite to becoming a politician. Politics would become the defining love affair of Tyler’s life, one he was far more passionate about than his wife Letitia, who he married in 1813. That was more about fulfilling the Southern gentleman’s obligation to marry well and produce children than any sense of romance. And produce children, they did: 8 of them between 1815 and 1830.

Tyler’s first taste of politics came in 1811, when he was elected to the Virginia House of Delegates, serving there for five years. In 1816, he seized an opportunity to get himself elected to the United States House of Representatives, and would thereafter spend half the year in Washington, DC tending to the people’s business, which caused an unfortunate drop in the revenues of his own business. It was difficult to maintain a thriving legal practice at home when he spent so much time away, and revenues at his plantation suffered when he wasn’t there personally supervising it. Tyler would spend much of his life in debt, relying on borrowing money from friends and from the bank to keep himself afloat.

In Congress, Tyler became more well-known for what he opposed than what he supported. Almost from the moment of its founding, there had been an argument about which entity should have more power in the United States: the federal government or the individual states that divided up the country. Tyler came down firmly on the side of “states’ rights,” and in this, like with most everything else, he emulated his father. Judge Tyler had tried unsuccessfully to prevent Virginia from ratifying the Constitution back in 1787, and when that failed, he became what was known as a constructionist. Constructionists believe that the federal government can’t do anything that isn’t explicitly permitted to it by the Constitution. Their opponents, variously known as consolidationists or centralists, believe that the federal government can do anything that the Constitution doesn’t specifically prohibit. These two arguments have dominated American politics for almost 250 years and will likely keep doing so in the future.

Ideological Purity

John Tyler, as a believer in states’ rights and constructionism, spent most of his time in Congress opposing bills he believed were unconstitutional. At the top of his hit list was central banking. Alexander Hamilton’s First Bank of the United States had been dissolved when its charter expired in 1811, but President James Madison, a vocal critic of the bank, found himself facing an economic crisis in the aftermath of the War of 1812, and realized a second bank would have to be chartered to manage the nation’s money.

When John Tyler and other southern lawmakers attacked the bank as unconstitutional, it’s important to keep in mind that the reason they were so opposed to it was because central banking tended to favor the commerce class, like businesses and manufacturers, most of whom were concentrated in the North. It didn’t benefit the planter class that dominated the southern economy, because their wealth was concentrated in assets, primarily land and slaves, as opposed to cash. And John Tyler was absolutely one of the planter class: he maintained a number of farms and plantations throughout his life, all of which were operated using slave labor. He saw no reason why things should change, and why would he? The present system already rewarded him. As a result, most of his constitutional stands were made just as much out of a sense of self-interest as from ideological purity.

However, it was for ideological purity that he became famous as a politician, not only as part of the House of Representatives, but also through two more stints in the Virginia House of Delegates, a two-year term as Governor, and as a US Senator from 1827 to 1836. He became known as a “man of principle,” someone who stuck to his states’ rights beliefs no matter what. This was epitomized in 1836, when he resigned from the Senate following a dispute with President Andrew Jackson.

But while he was making a name for himself in Washington, his home life suffered. His frequent absences continued to play havoc on his finances, and his children largely grew up without him, frequently communicating with their father only through letters. As for his wife, her many pregnancies left her in ill health. She was frequently bedridden, especially after 1839, when she suffered a stroke. She also suffered from what 19th-century doctors called “hysteria,” which was frequently triggered by her husband’s impending departure from home for the capital. Tyler himself was often ill, plagued with stomach ailments and other illnesses. Some medical historians have guessed that he suffered from Guillain-Barre Syndrome, an autoimmune disorder. Less is known about what ailed Letitia, since “diseases of the mind” tended to be kept private back then to avoid a scandal, but the most common guess is severe depression.

His Accidency

In 1840, John Tyler’s political career seemed to be over. After his resignation in 1836, he’d broken with Andrew Jackson’s Democratic Party, which had caused him to gravitate to their opponents, the Whigs. But Tyler didn’t like much of the Whig platform either, which was dominated by Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky. Clay, considered one of the 19th century’s most brilliant politicians, was the champion of centralization, having been an architect of the Second Bank of the United States, and when Andrew Jackson successfully killed it in 1836, Clay vowed to start another one.

1840 was the great chance for the Whigs to seize power and make Clay’s dreams a reality. The country had been gripped by an economic depression since 1837, and many blamed Democratic President Martin Van Buren and his party’s fiscal policy for it. At the party’s nomination convention in Harrisburg, the Whigs eventually settled on General William Henry Harrison as their candidate for President, but who would be his running mate? Nobody seemed to want the job of being Vice President, and it isn’t hard to see why: it was considered a political dead end. In those days, VPs had little to do besides preside over the Senate, and they only voted in that body to break a tie. And it wasn’t seen as a natural stepping stone for the Presidency either: between 1800 and 1968, only one man who had previously served as Vice President had been elected President in his own right.

After several viable candidates turned them down, the Whigs turned to Tyler, who accepted, and the ticket was complete. The Whigs won big in the 1840 election, on the backs of “Tippecanoe (pronounced Tippy-Canoe) and Tyler Too,” a popular campaign slogan that referred to General Harrison’s famous victory in the Battle of Tippecanoe in 1811. Not only did they win the White House, but swept to majorities in both houses of Congress as well. Henry Clay believed he had a mandate from the American people to enact his legislative agenda, and nothing appeared to stand in his way.

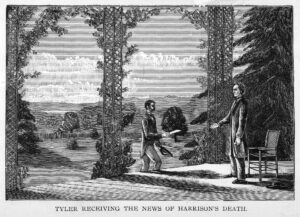

But fate was about to change the course of American history. On April 4, 1841, only a month after being sworn in as Vice President, John Tyler woke up to a knock on his door in the middle of the night. The news he received was grave: President Harrison was dead, a victim of pneumonia. He was needed in Washington immediately.

This was the first time that the constitutional line of succession needed to be used, and it immediately provoked confusion. No one was sure if John Tyler assumed the office of President itself upon the death of William Henry Harrison, or if he remained Vice President and merely assumed the duties of President until a new one could be elected. Constitutional confusion was averted when Tyler himself decided that he was now the President: he took the oath of office the next day, and for the rest of his life, he would return all mail that addressed him as “Vice President Tyler” or “Acting President Tyler” unopened.

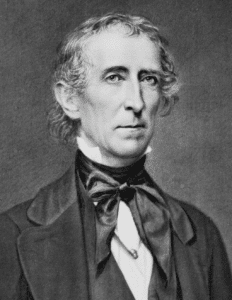

This set a precedent: in the seven subsequent cases where a President died in office, the Vice President has taken over after taking the oath of office. The Line of Succession was eventually clarified with ratification of the 25th Amendment to the Constitution in 1967. Still, it wasn’t all smooth sailing for John Tyler: for the rest of his term, his opponents derided him as “His Accidency” because of the way he’d assumed the office.

President Without a Party

John Tyler’s presidency was largely defined by what happened in those first few months after he assumed office. In the summer of 1841, a special session of Congress was called to address the ongoing financial crisis. Twice during that session, Henry Clay and the Whigs passed bills to create a national bank that they believed was needed to right the economic ship, and twice they were stymied when President Tyler vetoed the bill. As a result, nothing was done, and the Whigs looked impotent. This enraged Clay, whose electoral landslide was now falling to pieces all around him, but in hindsight, it hardly seems surprising, since Tyler had always been opposed to a central bank. The real question is why the Whigs would have risked putting him on the ticket in the first place? Harrison was 68 years old, an old man by 19th-century standards, there was always a risk of his dying in office. It seems the only answer is that nobody thought of it as a possibility: eight presidents had come and gone before Harrison, all of whom completed their terms without issue.

Whatever the reason for putting him on the ticket, the Whigs surely regretted doing so now, and they took their wrath out on John Tyler by ejecting him from the party in the fall of 1841, leaving him as a President without a party. The entire Cabinet Tyler had inherited from Harrison resigned, except for Secretary of State Daniel Webster. Tyler had few friends in Washington: the Whigs now hated him, and the Democrats, though they were delighted to see their opponents’ agenda shredded like this, weren’t willing to accept him into their ranks either, not with Andrew Jackson still as their leader.

Tyler would go up against the Whigs again in 1842, this time over the issue of tariffs. With federal income tax still decades away, import duties were one of the few ways the federal government made money. Once again, the issue split on sectional lines: northern states favored high tariffs because they protected their industries from European competition, while southern states hated them because they impeded their exports of cotton to the textile mills of Great Britain. Tyler, as a southerner, favored free trade, but like many idealists who find themselves in positions of executive power, he discovered that to actually run the country, he needed to raise tariffs, not lower them. The federal government was running out of money in 1842, there was a real risk of the United States being unable to pay its bills.

Still, for months, Tyler battled Congress over how much the tariffs should be raised, whether it should be a temporary or permanent measure, and over the fate of distribution, an emergency program that gave the profits from federal land sales to the states so they could pay off their own debts. He vetoed two more bills that summer before an agreement that satisfied nobody was finally worked out. His bridges with the Whigs were now well and truly burned, and Henry Clay resigned from the Senate; everyone knew it was to prepare for his run for the Presidency in 1844. There was even talk of impeaching the president for the first time in history, though grounds to do so were never found.

Lone Star Fever

Compounding Tyler’s misery during this period was the death of Letitia. Tyler’s wife passed away in 1842 following a second stroke, one of three first ladies to die while her husband was in office. For the second time in two years, the White House was in mourning.

The Tyler administration’s only major success during this period was ratification of the Webster-Ashburton Treaty with Great Britain, which settled a long-running border dispute between the state of Maine and the Canadian province of New Brunswick, as well as fixing the modern border between Minnesota and Ontario. But that was basically it. Tyler, it seemed, had no real policy platform of his own to offer up: everyone knew what he was against, but what was he actually for? Tyler himself didn’t seem to know most of the time, he irritated even his closest associates with his tendency to waffle back and forth on various issues, changing his mind multiple times and confusing everyone around him.

By the end of 1843, however, Tyler believed he’d figured out an issue that would cement his legacy as President, and might even boost his third party run for re-election: the annexation of Texas. Since 1836, the Republic of Texas had operated as an independent country following its victory in the Texas Revolution over Mexico, but all along Sam Houston and the Texan leadership had been trying to convince the American government to annex them. Both the Jackson and Van Buren administrations had ignored them, worried that doing so would spark war with Mexico, but Tyler, a firm believer in manifest destiny, saw Texas as a potentially valuable part of the Union, and didn’t think the Mexicans would risk a war to stop the US from taking over. He had Texas fever, and set his Secretary of State, Abel Upshur, to work on making annexation happen.

He faced an uphill battle in Congress though, with the issue of Texas lying not only on party lines, but sectional ones as well. The addition of Texas as a slave state would upset the delicate balance of power kept between slave states and free states since the Missouri Compromise of 1820, and Northern states weren’t keen to see the “slave power” gain an even more dominant position in national politics than they already had. Still, in the first two months of 1844, it seemed like the administration had enough support for annexation in the Senate, and a treaty was being worked out with the Texans.

Then, disaster struck: on February 28th, 1844, President Tyler, members of his cabinet, and hundreds of other guests took a ceremonial cruise down the Potomac (pronounced Pot-toe-mock) River onboard USS Princeton, a newly built US Navy corvette. The ship’s captain, Robert F. Stockton, took great pleasure in test firing a 27,000 pound naval cannon nicknamed “Peacemaker” for his guests. The gun was fired twice without incident, but when Stockton pulled the lanyard a third time, the gun barrel exploded, showering the deck with deadly shrapnel. Six men were killed, including two members of Tyler’s Cabinet: Secretary of State Upshur and Secretary of the Navy Thomas Gilmer. Fortunately for Tyler, he was below decks when the accident occurred. Had he been killed, history would have looked very different, as without a Vice President to replace him, the President Pro Tempore of the Senate, one of Henry Clay’s allies, would have become President.

Also killed in the explosion was David Gardiner, a prominent New York attorney and friend of President Tyler. Gardiner’s daughter, Julia, had been carrying on a prolonged courtship with the President for over a year, despite the fact that Tyler was thirty years older than she was. Oddly enough, the death of her father provided the push Julia Gardiner needed to finally agree to marry Tyler after rejecting him twice, and they were wed four months later, the first Presidential wedding in American history.

The Traitor President

The death of Secretary Upshur, the lead negotiator on the Texas treaty, complicated matters immensely. His replacement, John C. Calhoun, was one of the most famous pro-slavery politicians in the country, and he created a scandal when he wrote in a letter to a British minister that the reason the US was annexing Texas was to protect slavery from British interference. As a result, abolitionists, Whigs, and anyone who feared war with Mexico all came out against annexation. The Senate rejected his treaty in April.

The election of 1844 turned into a referendum on annexation. With no chance of being elected himself, Tyler decided to play spoiler, forcing the Democrats to nominate a pro-annexation candidate, James K. Polk, in exchange for dropping out of the race himself. This maneuver foiled Tyler’s adversary, Henry Clay one more time, as he was defeated by Polk in the election. Instead of a treaty, Tyler ensured Texas’s place in the Union by a joint resolution of Congress inviting them to join, which was signed by the President on his last day in office, March 3, 1845.

As feared, the annexation of Texas sparked conflict. The Mexican-American War would last two years and claim some 40,000 lives. As part of the treaty negotiations, Mexico ceded to the US not only Texas, but a huge swath of territory in the southwest, which would become four new states. The addition of so much new territory also inadvertently set the North and South on a collision course with each other that would end a decade later with civil war.

This mostly seemed beyond the concern of John Tyler, though. After leaving office, he retired to a new plantation in Virginia he named “Sherwood Forest.” He largely withdrew from politics, preferring the life of a gentleman farmer, overseeing some 70 slaves as they grew wheat and corn for him. His life with his second wife was certainly much happier than with his first: everyone who met with the Tylers indicated how much John and Julia loved each other, despite their dramatic age difference. They also had a bunch more children: 7 in all, for a total of 15 between two wives, the most of any President. The last of his children, Pearl, was born in 1860, when John was 70 years old! This unusual circumstance, combined with a similar proclivity on the part of one of his younger children, Lyon, is the reason why John Tyler is the oldest former president to still have a living grandchild: Harrison Ruffin Tyler, age 94.

Tyler probably should have stayed out of the secession crisis that swept through the South in the aftermath of Abraham Lincoln’s election in 1860. It was like he couldn’t help himself, though, his addiction to politics rearing its head even in his old age. It probably shouldn’t be surprising that Tyler was the only one out of the five living former presidents who took the side of the Confederacy when the Civil War broke out, considering he was also the only one of the five who was from the South and a slaveholder. But he went beyond just supporting the South: he actively called for Virginia’s secession, and was elected to the Confederate House of Representatives. Doing this earned him the moniker “Traitor President” in the North, ruining forever what was already a bad reputation.

Before he could take his seat in the rebel Congress, however, Tyler became ill. His persistent ill health had finally caught up with him, and he died on January 18th, 1862. His death was only acknowledged in the southern states: Lincoln’s administration gave Tyler none of the honors that would have been expected for a former president, the Northern press basically ignored his death or reported on it perfunctorily, without tribute or emotion. He was buried in Richmond’s Hollywood Cemetery.

Today, John Tyler has been largely forgotten by the American public, just another 19th-century President’s name to memorize in elementary school and then forget about. For a man who was obsessed with his presidential legacy, who spent nearly his entire post-presidential life defending what he’d done from 1841 to 1845, to be relegated to American ignominy would probably be the ultimate insult. Even the South in the years after the Civil War tried to forget about Tyler, since a slaveholding former President undercut their adherence to the “Lost Cause” rhetoric that was embraced by southern historians at the end of the 19th century. Some people would argue that’s just what he deserves, that a man who couldn’t see past his own personal principles for the good of the country and defended the South and the practice of slavery even to the point of war shouldn’t be remembered fondly.

In life, John Tyler was a President without a party. Today, he’s arguably something worse: a President without a legacy. Or at least, not a GOOD legacy.