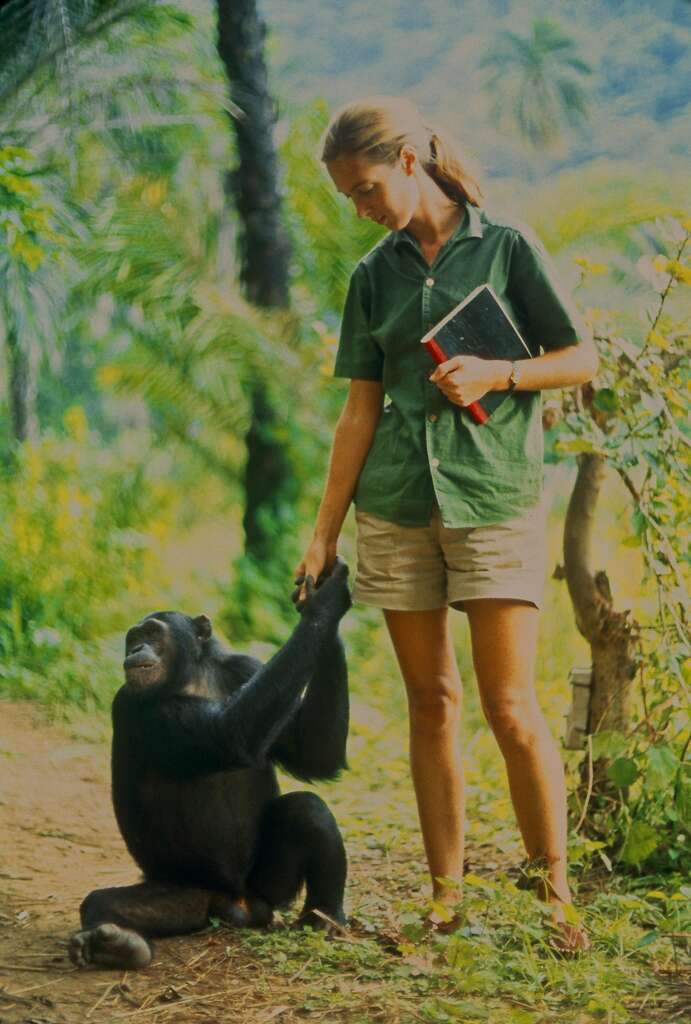

Best known as the young, golden-haired woman living alongside humankind’s closest relatives, this scientist-turned-activist has devoted her life to understanding, and working to save chimpanzees from near extinction. Her unorthodox methods of observation revolutionized how scientists conduct animal research in the wild, debunked long-held assumptions about primate behavior, and showed the world how much we have in common with the animal kingdom.

Let’s learn more about the legendary British primatologist, ethologist, anthropologist, and UN Messenger of Peace, Jane Goodall.

Early Life

Valerie Jane Morris-Goodall was born in London, England on April 3, 1934. She was the oldest of two girls, born to father Mortimor, an engineer-turned-race car driver, and to mother Vanne, a successful novelist. Exactly four years following Jane’s birth, her younger sister Judith was born and completes the family. The happy foursome would be short-lived, however. With World War II declared in England in 1939, Jane’s father enlisted and was posted to France. From then on, he would become a distant figure in Jane’s life, only rarely coming home when he was on leave. After the allies declared victory and war was over, the Goodall marriage ended in divorce. A few years before Jane must have know it was coming, the youngster writing a heartfelt letter to her father pleading him to wait until she was 12.

The divorce of Jane’s parents may have had a greater impact on her if her mother hadn’t been such an influential and supportive parent. Jane says it was her mother, primarily, that encouraged her to live out her passions, saying,

“Jane, if you really want something, and if you work hard, take advantage of the opportunities, and never give up, you will somehow find a way.”

Her mother would later play a role in Jane’s early career, traveling with Jane and staying on at the camp at the Gombe Reserve.

Jane spent the majority of her childhood growing up in her maternal grandmother’s 1872 Victorian house in the resort town of Bournemouth, on the south coast of England. They had a yard, with a garden and trees — where Jane spent most of her free time.

Surrounded by women, Jane shared the residence with her mother, sister, grandmother, and two aunts. It was a happy home, and a place Goodall, now in her 80s, goes back to when she needs to relax and recharge. She says, “all my childhood books, the trees I climbed as a child, the cliffs where I walked…. I am blessed in this way.”

Fascination with Wildlife

Young Jane developed an early fascination with wild animals. At just over a year old, Jane’s father gifted her a lifelike, three-foot tall stuffed chimpanzee that she affectionately named Jubilee and carried around with her everywhere. Jane’s mother’s friends were quite horrified by the toy chimpanzee, fearing it would give the young toddler nightmares. Quite the opposite, Jane loved the toy and still has it over 80 years later!

Being that Jane devoted her life to researching and saving chimps, the early gift of a stuffed chimpanzee seems like the ultimate foreshadowing. But Jane admits she is keen on all animals, and would have studied another species if the circumstances had been different. In fact as a girl, Jane did not limit herself to learning about one kind of animal. Jane would often be outside the family home in the yard, quietly observing, sketching or writing notes about birds and other creatures. Her family had a host of pets including a tortoise and a dog, and the young Jane took in many more including racing snails, caterpillars, a lizard and a canary. Jane was an avid reader too, some of her favorite books included Doctor Doolittle, Tarzan, and The Jungle Book. Reading these books ignited a desire to go to Africa some day, to observe and write about wild animals.

Jane was also a curious and patient youngster. Once when Jane was five years old, her parents could not find her and presumed her missing. As panic ensued and a search began, it turned out Jane had been sitting in the hen house waiting for the chickens to lay eggs. This quiet observation and persistence is the hallmark of how Goodall would later conduct her research at Gombe Stream.

While Jane entertained fanciful thoughts of Africa and longed to be outside in nature, she was still young and enrolled at the Uplands Private School. By all accounts, she was a good student but felt the routine of the classroom unbearable. At 16 she confided in her diary writing, “Woke up to be faced by yet another dreary day of torture at that gloomy place of discipline and learning, where one is stuffed with ‘education’ from day’s dawn to day’s eve.” Despite these feelings, she managed to embrace her school studies and finish strong, focusing on her interests in biology and English. She even won two school prizes for essay writing.

In 1953 and at the urging of her mother, Jane enrolled in the London’s Queens Secretarial College and graduated one year later. After receiving her qualification, Jane held clerical jobs in Bournemouth and Oxford University. She also sometimes waited tables, and took a part-time job with a film company. Still, Jane never gave up on her dream of going to Africa even if the idea seemed far-fetched.

African Adventure

In 1955, Jane Goodall received a letter from Clo, an old school friend, with an invitation to come to Kenya. The day had finally come, it was the opportunity she had been waiting for. She saved hard for the fare and in March 1957, embarked on a three-week journey by ship. Soon after arriving in Kenya, Jane took a job in the capital city of Nairobi and met the famed British paleontologist Louis Leakey, who was then the curator of the natural history museum, the Coryndon Museum. Jane was just 23 years old.

Leakey asserted Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution and believed humans originated in Africa. He was motivated to find the missing link and was searching for just the right person to study primates in the wild, rather than in captivity. Research of apes in their natural habitat had not been carried out before in this manner and Leakey saw in Jane the perfect candidate to conduct the study. Not only did Jane exhibit the enthusiasm he was looking for, but she also had the temperament to sustain long periods of time in the African bush, “with a mind uncluttered and unbiased by theory.” Up until this time, Goodall had no formal scientific training or academic credentials that qualified her to conduct such a study. Not to mention, women scientists were practically unheard of during the 1950s and 1960s. Nevertheless, Leakey took a chance on the young woman, first hiring her as a secretary and then sending her to Gombe Stream Reserve in Tanzania in 1960. Jane would earn her Ph.D. later, in 1965, from Cambridge University. The degree would earn Jane respect in the field and allow her to receive funding for research.

Gombe Stream

In 1960, at the age of 26, Jane Goodall embarked for the Gombe Stream Reserve, now part of Gombe National Park in Tanzania. Gombe is bordered by the longest lake in the world, Lake Tanganyika, in the Kigoma region of the country. In 1960 when Jane began her research, the forests of Gombe were part of a continuous chain through Burundi, Rwanda, and Uganda, and stretched westward to the great Congo Basin. Jane’s destination was only accessible by boat and the land was characterized by steep valleys and lush, green rainforests. The African bush and waters were alive with many species of wildlife, birds and fish. Today, it remains one of the best places on earth to observe primates in their natural habitat.

Goodall’s mission was to learn everything she possibly could about the wild chimpanzees while in Gombe. Her mother accompanied her on the trip for the first few months, the local authorities believing a young British woman would never survive alone in the wilderness. Perhaps they were right, though the dangers of nature were less of a concern. At the time, civil war in the Congo had flooded Gombe with refugees. For several weeks, Jane, her mother and one cook, were forbidden to travel to the stream, and waited out the conflict in a prison camp until it was safe again.

Thinking back on her first day in Gombe, Jane recalled…

“Looking up from the shore to the forest, hearing the apes and the birds, and smelling the plants, and thinking it was very, very unreal.”

Jane’s early attempts at getting close to chimpanzees failed; she could get no closer than 500 yards. She found another troop, and established a pattern of consistent observation by appearing in the same spot each morning along the Kakaombe Stream near the chimps feeding area.

It was one male chimpanzee who allowed Jane within close range. She tempted him with the odd banana and named him David Greybeard, for his white-tufted chin. Once he allowed Jane to get close and watch him, other members of the troop started to feel comfortable and accept her presence. No other human, up until now, had ever gotten so close to chimpanzees in the wild. It would take two years for the chimps to show no fear of her and she was allowed to observe them almost as if she was a chimp herself. Jane imitated them, ate their foods, and spent time in the trees. She would become closely acquainted with over half of the 100 or so chimps in the reserve.

Much to the horror of some scientists, Jane gave all the chimps names like Flo, Fifi, Flint, and Mr. McGregor. During the time, one was careful not to give human characteristics to animals for fear of engaging in anthropomorphism. Researchers used numbers instead. Goodall would later recall, “These people were trying to make ethology a hard science. So, they objected – quite unpleasantly – to me naming my subjects and for suggesting that they had personalities, minds and feelings.” Critics aside, Jane continued the practice. She believed, that empathy was the key to detecting slight changes in mood or attitude, and those changes could provide insights into complex social processes.

Discoveries

Within weeks at Gombe, Jane was making new discoveries and turning conventional thought on its head. Making tools and using tools was thought to be an exclusive trait of humans, not animals. Yet, Jane witnessed David Greybeard using a blade of grass to extract termites from a mound and on another occasion, he stripped leaves from a twig to gain better access to his prey. This was the first recorded time in history another species had used or modified tools. Leakey was so excited, he famously exclaimed, “We must now redefine man, redefine tool, or accept chimpanzees as human.” He was surely exaggerating, but the discovery was a major blow to the notion of ‘man the tool maker.’

A few weeks after the toolmaking revelation, Jane observed David Greybeard eating what looked like a piece of meat. It was a piglet, and so the long-held theory of primates as strictly vegetarians, was debunked. Through Jane’s observations, the world would also learn chimps engage in cannibalism and warfare. Jane witnessed a brutal four-year war with a neighboring “tribe” that devastated the chimps. Male chimps also routinely patrol the borders of their territory and will attack a solitary male chimpanzee from another tribe to protect their area. This dark side of chimpanzee behavior Jane Goodall likened to gang activity.

Living amongst the primates, Jane observed that chimpanzees have complex brains and social systems. The “caste system” of chimpanzee society places the dominant male at the top, which is often ranked by how intense his performance is at feedings. Over the course of her research, Jane discovered chimps to develop long-term bonds with each other, have ritualized behaviors and a primitive “language” with 20 unique sounds. Chimpanzees possess individual personalities and communicate through touch and body language. They kiss and embrace each other, give pats on the back, shake their fists, and engage in a whole variety of other non-verbal ways.

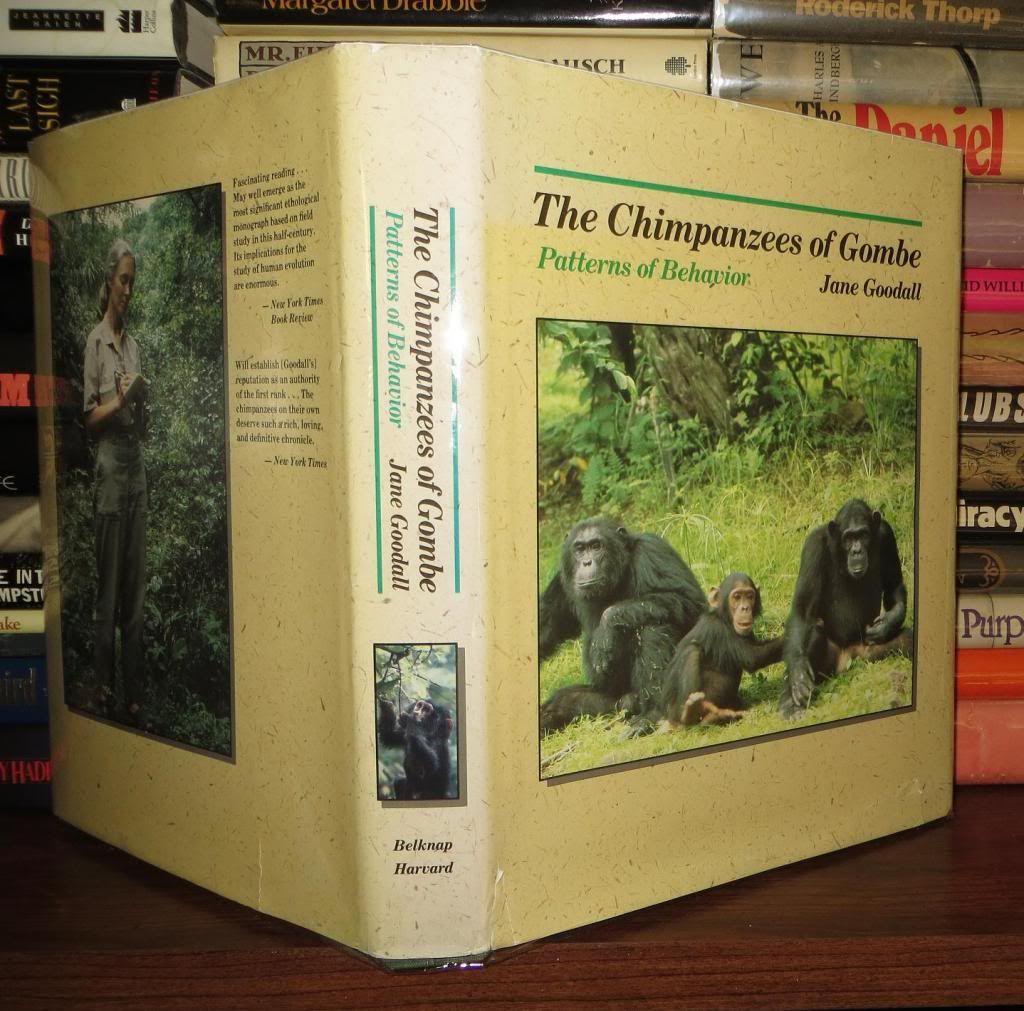

Jane noted the males do not play an active role in the family; this is left up to the females. Jane observed the strong bond in the mother-child relationship, and found that maternal instincts are taught, not inherent. Chimpanzees learn through observation, imitation, and practice. The chimpanzees with good mothers, who were above all else supportive, ended up being good mothers themselves. The ones who were poor, ended up having female offspring that was also poor at mothering. Jane even theorized that chimps may have a sense of self, and perhaps, a spiritual connection. Jane’s research concluded that mother-centric groupings, along with sex, food sharing, and grooming, are the essential components of chimpanzee society. Goodall’s publication, The Chimpanzees of Gombe: Patterns of Behavior, is the definitive work on the behavior of chimpanzees. It would become the core body of work used to establish chimps, gorillas, and bonobos as hominids.

Celebrity & Activism

The early discoveries of toolmaking and meat-eating chimps, and the idea of a young woman living in the jungle, caught the interest of National Geographic and in 1962, they sent the dashing Dutch photographer, Baron Hugo van Lawick to film her work. The two fell in love while on assignment and they wed in 1964. Three years later, they had their son Hugo Jr., who she called “Grub.” Life seemed idyllic for Jane, doing what she most loved; being with, and writing about, chimpanzees. Van Lawick’s film, Miss Goodall and the Wild Chimpanzees, aired in 1965 and thrust Jane into the spotlight. In the same year, Jane received her Ph.D from Cambridge. Even though it was Leakey’s idea, and he pushed Jane to pursue her Doctorate, she acknowledged it was important saying, “Cambridge taught me to think in a scientific way, so I could stand up to people. It taught me to think logically, I loved it, and I loved analyzing the data; it was a very important part of my development.”

Jane and Hugo’s marriage lasted a decade and by 1974, the pair called it quits, yet they remained on good terms. She would marry Derek Bryceson, member of Tanzanian parliament and Director of Tanzania’s National Parks the following year. They had five good years together and made their home at Lake Tanganyika until his death in 1980 to cancer. Jane was devastated by the loss but she came to terms with it.

“…I went to Gombe, and the forest is very healing. You get this endless cycle of living and dying, and things fell into perspective.”

In 1971, Jane Goodall published one of her most popular and well-known books, In The Shadow of Man, on the Gombe chimps where her vivid descriptions brought them to life and bridged the gap between science and entertainment. Jane published many more books after, held a professorship at Stanford University, and was appointed honorary visiting professor of Zoology at the University of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania. In 1977, Dr. Goodall founded the Jane Goodall Institute (JGI) with a mission to protect the chimpanzees and further the research at Gombe.

The soft-spoken Jane seemed an unlikely celebrity but she would find her academic respectability and popularity an advantage when speaking on behalf of the chimps she loved. Over the course of her research at Gombe it became increasingly clear the wildlife there, including the chimpanzees, were at a significant risk. In fact, by the 1980s, chimpanzees were an endangered species. Their home, and resources were being destroyed at an amazing rate.

After attending a conference organized by the Chicago Academy of Sciences in 1986 to coincide with the publication of The Chimpanzees of Gombe, Goodall found herself at a turning point. At 52, and after 25 years of field research, Jane went on the road to educate the public on the vanishing habitats, the “bush meat” trade, animal trafficking, and the unethical treatment of animals used in modern medicine and for scientific research.

In 1990, the revelation came that Jane must turn her attention to humans in order to save her chimps. While flying over Gombe, she saw the hills stripped bare by deforestation. The local villagers were responsible, having over-farmed their land. With little options left, they had taken the trees in the national park to sell as timber in order to survive. At that moment, Jane realized then that unless you address poverty, and work to improve the lives of villagers, you can never expect to conserve the land and save the wildlife.

“Everything’s interconnected. You learn that in the rainforest,” Jane explains.

Soon after, the JGI launched programs focused on education, family planning, water management, sustainable agriculture, and microcredit for women.

Accomplishments

Thanks to her work with the Jane Goodall Institute’s Lake Tanganyika Catchment Reforestation and Education Project, the Gombe chimps now have “three to four times more forest than they had ten years ago.” Her work on ethical treatment of captive chimps led the medical community to steer away from their use in cross-species organ transplant, also known as xenotransplanation. And, Goodall has made strides to phase out the use of chimpanzees in medical research. Goodall works tirelessly, an average of 300 days per year, to spread the mission of the JGI. The Institute has offices around the globe with programs primarily in Africa to involve the local people in community-centered conservation. Another initiative, the Roots & Shoots program, is in operation in over 130 countries and works to foster environmentalism and peace among the world’s children. Goodall’s passionate fight to preserve the world’s chimpanzee population has included service on the Save the Chimps board, the world’s largest chimpanzee sanctuary located in Fort Pierce, Florida.

Over her long career, Goodall became the world’s expert on primates. Her fieldwork has led to the publication of numerous articles and five major books including, My Friends the Wild Chimpanzees, In the Shadow of Man and Through a Window. She has also written a number of children’s books, such as Grub: The Bush Baby, Chimpanzees I Love and My Life with the Chimpanzees. Countless people, over multiple generations have gotten to know her work through the National Geographic magazine, television programs, and IMAXX film, Jane Goodall’s Wild Chimpanzees. Jane, A new documentary film by Brett Morgen was released in 2017 to critical acclaim that features over 100 hours of archived National Geographic footage. The trailblazer Jane Goodall is still captivating audiences all this time later.

Goodall has received numerous honors and awards including the Gold Medal of Conservation from the San Diego Zoological Society in 1974, the J. Paul Getty Wildlife Conservation Prize in 1984, the Schweitzer Medal of the Animal Welfare Institute in 1987, the National Geographic Society Centennial Award in 1988, the Kyoto Prize in Basic Sciences in 1990, the National Geographic Society Hubbard Medal for Distinction in Exploration, Discovery and Research in 1995, In 2002, she was named Messenger of Peace by the United Nations, and in 2003, a Dame of the British Empire by Queen Elizabeth II of England, and in 2006, she was honored with 60th Anniversary Medal of the UNESCO and French Legion Honor. She also holds honorary Doctorate degrees from many prestigious universities around the world.

Legacy

Jane’s research continues at the Gombe Stream Research Centre, established by Goodall in 1965. It is the longest-running study of chimpanzees the world has seen. The center hosts visiting researchers and continues to further our understanding of chimpanzee health, group dynamics, diet, and more. The information gathered here can also inform conservation efforts. These days, Jane visits the center at least twice per year but all the chimps she knew and loved have passed on.

Jane’s legacy is more than her contributions to science, or activism. Her determination and body of work inspires us to believe in ourselves, and remember our connection to nature and what we leave behind. She wants us to think about the earth’s future and our role in protecting it…

“I care passionately about nature. I care passionately about children. I have three grandchildren. I think about their children. If we can’t do things differently, what is the world going to be like in 50 years?”

Above all else, Jane has taught us, it is up to us to make change. “Every individual matters. Every individual has a role to play. Every individual makes a difference. Only if we understand, will we care. Only if we care, will we help. Only if we help shall all be saved. The least I can do is speak out for those who cannot speak for themselves.”

Jane Goodall’s Video Biography