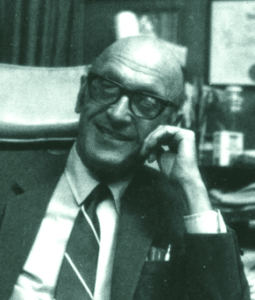

On November 22, 1963, nobody knew who Abraham Zapruder was. The Dallas businessman was happily living a perfectly ordinary life when he left his office to go to Dealey Plaza to take some film of the President John F. Kennedy’s motorcade as it passed through the streets of Dallas with his home movie camera. What happened next was shocking and horrifying to the entire nation: in broad daylight, the President was brutally murdered, right in front of his wife and a hundred other witnesses.

Abraham Zapruder not only had a front row seat for one of the most horrific crimes in American history, he actually filmed it with his camera: the only person in the plaza that day who’d captured the entire assassination from start to gruesome finish. Now he had to decide what to do with it, all the while managing his own grief at the slain President and the trauma that came with witnessing a man murdered in cold blood right in front of you.

What he’d filmed that day, known to history as “the Zapruder Film,” has become a central part of telling the story of JFK’s assassination: used to “prove” what happened by both official government investigations as well as by the thousands of amateur sleuths who had their own theories about what had happened to the President. Every single frame of the film has been analyzed, scrutinized, and stared at by thousands of people, all of them trying to find clues to determine who “really” killed JFK. It has also raised important questions about the role of violence in America’s media, whether it was more important for people to see for themselves what had happened, or to protect the dignity of a beloved man who’d been gunned down in his prime.

None of this could have been foreseen by the man who took the film, however. Abraham Zapruder would be haunted by his film for the rest of his life, and the film would haunt his children and grandchildren after that, even today, decades after the film passed out of their possession for good. This is the story of a man and his camera, who set out to make a movie for his grandkids to see, and instead ended up making the most famous home movie of all time.

Man Makes Good

Abraham Zapruder was born on May 15, 1905, in the Ukrainian city of Kovel, then part of the Russian Empire. His childhood was anything but idyllic: the Zapruder family was Jewish, living in a part of the world that was historically hostile towards Jews. Anti-semitic violence was a fact of life in this period, and that was BEFORE World War I came and turned all of Europe into a battlefield. Kovel was fought over multiple times between the Central Powers and Russia, culminating in a large battle in 1916 that resulted in 50,000 casualties.

The violence of the area, particularly against Jews, affected the Zapruder family personally: Abraham’s older brother, Morris, was pulled off a train by Russian or Polish guards and summarily executed in front of his family, for no other reason than he “looked Jewish.” Like many Eastern European Jews, the Zapruders decided to escape the poverty and discrimination of their homeland by immigrating to America. Abraham and his family passed through Ellis Island in 1920, after crossing the Atlantic aboard the ocean liner SS Rotterdam.

Like many recently arrived immigrants, Zapruder found work in the huge New York City garment industry, and overcame his limited education in his home country, teaching himself English in the process. He married his wife Lillian in 1933, it was a happy marriage that resulted in two children: Myrna and Henry. In 1941, the family moved to Dallas, where Abraham had been offered a job with a local clothing company. A decade later, Zapruder decided to go into business for himself: he and his partners would found their own dressmaking company called Jennifer Juniors that specialized in making lower cost versions of expensive couture dresses sold in stores like Dallas’ own Neiman Marcus.

It was a successful operation full of loyal employees who described Zapruder as a tough, but fair boss who genuinely cared for their wellbeing. Everyone who worked for him called him “Mr. Zee,” family and friends called him Abe. By 1963 the 58 year old was considering stepping back from the business and retiring: he and Lillian wanted to travel, and after a lifetime of hard work, Zapruder was looking forward to spending more time with his hobbies: playing music, tinkering around his house and garden, and spending time with his grandchildren, who he adored. It was a happy, ordinary life, not much different from the experience of millions of Americans, even today. But all that was about to change in one vicious moment of violence.

Taking Some Pictures

Like much of the rest of the city of Dallas, Abe Zapruder was excited when he arrived at work on the morning of November 22, 1963. President Kennedy was visiting Texas ahead of his 1964 re-election campaign. He and the First Lady had spent the night in neighboring Fort Worth, and today, he was scheduled to visit Dallas. Thanks to it being reported in advance in the city’s newspapers, the employees of Jennifer Juniors knew that the presidential motorcade was going to pass almost right in front of the Dal-Tex Building, where they worked. If they walked a short way across the street to Dealey Plaza, they’d have a front row seat.

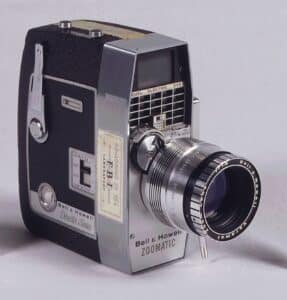

Anyone who knew anything about Abe Zapruder knew he loved making home movies. It had been a hobby of his for three decades by 1963, his home had boxes upon boxes of film reels, mostly showing his family, stretching back to the 1930s. The year before, he’d purchased a new Bell & Howell Zoomatic camera from a jewelry store in Dallas, considered top of the line among amateur movie makers at the time. It certainly wasn’t cheap: the camera retailed for around $200 in 1962 (equivalent to more than $2,000 in today’s money), not to mention the special 8mm Kodachrome film needed to be mailed to a Kodak laboratory in New York to be developed.

Most people who knew the Zapruder family also knew they loved the Kennedys. Abe had been a Democrat stretching back to the days of Franklin Roosevelt, but he was particularly enthusiastic about JFK. His whole family took after his example: his daughter Myrna had volunteered during Kennedy’s 1960 election campaign, and his son Henry, a recent graduate of Harvard Law School, had just started a new job with the Justice Department in Washington DC. Like many American women, the Zapruder ladies modeled their wardrobes after Jackie Kennedy.

So it seemed an obvious question for his employees to ask Abe Zapruder that morning: “Are you planning to film the motorcade?” He’d talked about doing it a few days earlier: a once in a lifetime opportunity to make a film to show the grandkids someday. But now Zapruder wasn’t sure: the crowds were expected to be huge, would he even be able to see the President, much less film him? In any case, he’d left his camera at home. But his friends at Jennifer Juniors knew Abe, knew he’d kick himself if he didn’t take advantage of this opportunity. So they encouraged him to go home and get it, which he did. The whole firm was given a long lunch break so they could go see the motorcade if they wanted to, and around noon, Zapruder left his office and headed for Dealey Plaza.

Tragedy in Dealey Plaza

Zapruder spent several minutes walking up and down Elm Street, trying to find a good angle to film the motorcade. It was here that some of his employees found him, and his receptionist, Marilyn Sitzman, suggested that he climb on top of a four foot tall concrete abutment that overlooked the street. Since Zapruder suffered from vertigo, Marilyn offered to stand behind him holding his coat so he would fall over if he became dizzy while filming.

It was a perfect vantage point, and at around 12:30 PM, the motorcade came into view, cheered by the crowds lining the streets to see it. When the first Dallas Police motorcycles came into view, turning left onto Elm Street from Houston Street, Zapruder began filming, but stopped when he realized that he couldn’t see the presidential limousine yet (he didn’t want to waste his film). At 12:35, Kennedy’s open-top limousine made the turn, and an excited Zapruder started filming again, not realizing that, as he did so, the barrel of a rifle was coming out of a sixth floor window approximately 185 feet behind him, in the Texas School Book Depository Building.

The beginning of Zapruder’s movie was no different than hundreds of other films and photographs taken that day of the motorcade, with President Kennedy seated in the back seat of the car, next to his wife, smiling and waving at the crowd. In front of him is the Governor of Texas, John Connally, and his wife, while two Secret Service agents are in the front seat. There is no sound in the film, so we can only imagine the sound of the first gunshot, which missed. Few people paid attention to it, thinking it might have been a car backfiring or a firecracker.

The second shot takes place while the limousine is temporarily obscured from Zapruder’s camera by a road sign. It struck Kennedy in the back of his neck, punching a hole in his esophagus before exiting his body and striking Governor Connally in his chest, wrist, and leg. As the car emerges from behind the sign, the President can be seen reacting to the shot, his arms coming up to his throat and leaning forward. Then, as the car passed directly in front of Zapruder, 65 feet away, there’s a third shot. This one strikes Kennedy in the back of his head, doing a massive amount of damage. A spray of blood, brain matter, and skull fragments is visible in the film, as the President collapses onto the seat next to the First Lady, who is visibly distraught. Then the limousine speeds away, the entire sequence having lasted less than ten seconds.

Aftermath

Abe Zapruder might have been the first man in America to realize that President Kennedy was dead: the fatal shot had happened right in front of him, and he instinctively knew that no one could survive that kind of injury. Since he’d seen the shooting through the viewfinder of his camera, he also knew that he’d captured it on film. In a daze, Zapruder climbed off the abutment, later claiming that he had no memory of the moments immediately after the shooting. While he was still in the plaza, holding the camera, a reporter for a Dallas newspaper, Harry McCormick, approached him: when he found out that the dressmaker had filmed the shooting, he went to find the head of the Dallas Secret Service, Forrest Sorrels, who came to Zapruder’s office to ask about it.

But before anyone could see what Zapruder had shot, the film inside his camera needed to be developed. This was not as easy as it sounded, because of the special Kodachrome film Zapruder was using. The offices of the local newspaper, as well as an ABC television station, were unable to process the film. The only place in town that had the capability was the Eastman Kodak laboratory out by the airport. As the police car carrying Sorrels and Zapruder arrived at the lab, they could see Air Force One taking off from Love Field, flying back to the capital with the body of President Kennedy, as well as new President Lyndon Johnson, on board.

After being developed, the film was taken to a nearby film studio so that three copies could be made of it. Then Zapruder headed down to the Dallas Police Department Headquarters, which was a chaotic scene: Zapruder caught sight of the suspected assassin, Lee Harvey Oswald, as he was being moved from one room to another. Two copies of the film were turned over to the Secret Service, leaving Zapruder with one of the copies, as well as the original film. For some unexplained reason, Sorrels never tried to take possession of the original film that was in Zapruder’s camera, which you might have expected him to do. There have been several conspiracy theories based on this, but the most likely explanation is that, in the heat of the moment, it simply never occurred to him to do so.

It was late at night by the time Zapruder arrived back home. The last twelve hours had been a truly trying ordeal for him, but it wasn’t over yet: he still had the film. And now he needed to decide what he was going to do with it.

Contracts and Investigations

Every local and national reporter in Dallas knew about Abraham Zapruder and his film by the morning after the assassination, and all of them showed up at his office, trying to get ahold of it. Contrary to popular belief, the Zapruder film is not the only film captured of the assassination: there were at least twenty other cameras in Dealey Plaza at the time of the shooting, and several of them caught still and moving images of parts of it. But Zapruder’s was the only one that captured the entire sequence from start to finish, including the graphic result of the fatal bullet: whichever media company got the film would have the journalistic scoop of the century.

Zapruder found most of the journalists to be pushy, ill-mannered, and unkempt, and while he showed the film to all assembled, he really only wanted to do business with one man: Richard Stolley, who represented LIFE magazine. Money was not his primary aim, even though he stood to make a substantial windfall by selling his film to the highest bidder. He’d had a nightmare that night, of walking through Times Square and seeing a carnival barker seeing tickets to “see Kennedy’s head explode.” Zapruder’s primary concern, as he explained to Stolley, was to prevent his film from being used in a way that would harm President Kennedy’s memory, or cause further suffering to Jackie. LIFE, at the time considered one of the most well respected publications in America, seemed to be best suited to do that.

LIFE eventually bought the film, and the copyright to it, from Zapruder for a total of $150,000 (just over $1.5 million in today’s money), promising to withhold the most grisly details of it from the public. The magazine would eventually publish stills from the film on five different occasions, though never Frame 313, which contained the head shot. As for the film itself, they kept it under lock and key, only allowing it to be viewed by official investigations into the assassination, particularly the Warren Commission of 1964. Zapruder testified before the commission, which determined that Oswald had acted alone when he killed Kennedy, while his film was considered the most important piece of evidence, since Oswald was dead, having been killed by nightclub owner Jack Ruby two days after Kennedy’s death, apparently in retaliation for killing the President.

Abraham Zapruder would be haunted by the assassination, and his film of it, for the rest of his life. He felt guilty that he’d accepted money for the film, worried that because he was Jewish, people would accuse him of profiting from Kennedy’s death, even start a backlash against Dallas’ Jewish community by local bigots. He donated $25,000 of the money he received to the widow of JD Tippit, the Dallas police officer that Oswald shot and killed less than an hour after he shot Kennedy. He died of stomach cancer in 1970 at the age of 65: he never used his Bell & Howard camera or took another home movie again.

The Smoking Gun

As the years passed and the initial shock and grief from President Kennedy’s murder faded, a number of people began to find the story put forward by the Warren Commission about what had happened to be implausible at best, and a cover up at worst. All sorts of conspiracy theories had sprung up by the end of the 1960s, accusing a number of shadowy organizations of being responsible for Kennedy’s assassination: the Mafia, Communists, right wing extremists, and (the most popular one) elements within the US government, including the CIA, FBI, even Lyndon Johnson. An entire cottage industry sprung up revolving around researching and publishing alternate theories about the crime.

For all of these researchers, the definitive piece of evidence that they looked to in order to “prove” their theory correct was the Zapruder film, which began to take on a life of its own separate from its namesake. But the problem was, the Zapruder film, at least, the moving image version, wasn’t available anywhere: LIFE had it under lock and key, and refused to allow anyone to use it, suing several parties for copyright violations along the way. Many people accused the publisher of either being part of a coverup, or holding out for some big payday in the future, but the truth was, the executives at LIFE were conflicted about what to do with it. They had originally bought it to keep people from seeing it, claiming that Americans weren’t ready to witness the horrific violence it contained on their TV screens. There was also no easy way to utilize the film that would be both profitable and “tasteful,” especially since, as a print magazine, film wasn’t their forte to begin with.

But as time passed and the calls of conspiracy grew louder, LIFE eventually decided to cut their losses and get rid of the film, returning it to the Zapruder family for the nominal sum of $1. For the rest of the century, Abe’s son Henry took over managing the film, in addition to keeping up with his busy legal practice. Unlike LIFE, he did allow people to access copies of the film, which was stored in the National Archives: historians, researchers, and the privately curious could get it at cost, while production companies that sought to profit from it were charged licensing fees. The only people who were turned away were people who wanted to use it for crass purposes, like a camera company claiming that the film would have come out much better had Abe Zapruder been using one of their new cameras.

In the 1990s, a protracted legal fight between the Zapruder family and the federal government was waged after passage of the JFK Act, in which the government promised to collect and make available all documents pertaining to the assassination to the public. As part of this, the government seized possession of the original copy of the film under eminent domain, the only time in American history this has been done for a historical artifact. The Zapruders, who thought the whole thing was silly because they weren’t planning to remove the film from the Archives anyway, and anyone who wanted access to it could have it, received $16 million from an arbitrator for the film in 1999. Soon after, they donated the copyright on it to the Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza, which preserves the location where Oswald fired the fatal shots.

A Most Important Film

The 26 second, 486 frame Zapruder film is considered one of the most important films in history, and certainly is the most scrutinized. There is of course no problem with access to the film by anybody these days, thanks to the Internet: there are thousands of copies of the film available to watch at the push of a button, including enhanced versions, slow motion, copies that focus on specific individuals, and more. Someone watching the film today might consider that the graphic nature of it was overstated, but those people aren’t considering the fact that, at the time, Americans were not exposed to anywhere near the level of violence in the media that they are today. Even modern productions that use the film tend to air versions of it that have had the headshot edited out of it, not only because it is graphic, but it is the President of the United States.

As access to the film expanded, and still no “smoking gun” that proved conspiracy emerged, the more extreme theorists started questioning the Zapruder film itself, claiming that the reason it doesn’t show what “really” happened is that it was altered or faked. Coming at it from this angle, whether they mean to or not, ropes poor old Abe Zapruder into the cover-up of Kennedy’s death. This, quite simply, is not fair to him, or to his family. Abraham Zapruder did not set out that day to make history, or to document it: he simply wanted to make a home movie, an innocent moment to share with people during his twilight years. He was not only an accidental witness to history, he was a casualty of it: though not physically wounded by the assassination, he certainly suffered from undiagnosed PTSD as a result of the trauma.

Abe Zapruder paid a heavy price for his film, regardless of how much money he got for it afterwards. We owe him a tremendous debt, since his film will be used for generations upon generations to better understand one of the most tragic episodes in American history. It seems the least we can do, whatever you believe about the Kennedy assassination, to leave Mr. Zapruder alone, to let him be remembered by his family for who he was, beyond the 26 seconds that changed his life.