There are many tales of people achieving all sorts of fortune and fame by selling their souls to the devil. Blues guitarist Robert Johnson is probably the most famous subject of that tall tale. The legend goes that he offered his soul at a Mississippi Delta crossroads, and in return he would receive musical success and talents beyond his wildest dreams. And, yes, to this day he is considered a pioneer of American blues guitar and songwriting. But the devil is in the details. And with a life so shrouded in mystery, it’s hard to separate fact from his very appealing fiction.

Humble Beginnings

Robert Johnson was born in Hazlehurst, Mississippi on May 8, 1911, spending much of his beginnings on a plantation in the Delta. His mother, Julia Major Dodds, was a daughter of slaves. Dodds had ten children with her husband, but Robert was born out of an affair with a field hand named Noah Johnson. Later in Robert’s childhood, Julia remarried and moved the family to Robinsonville, Mississippi.

Robert seemed to take to music quickly as a child, demonstrating keen musical ability both on the jaw harp and harmonica. That interest didn’t fade as he grew into his teens, as he was absent from school more and more, which his friends attributed to him studying music in Memphis. He would also play around with a makeshift instrument called a diddley bow, which was a wire attached to a house that a person could pull taut and hit with a stick, altering the pitch with a bottle that slides along the wire.

The early and teenage years of Robert Johnson are very much shrouded in mystery. Historians have had to lean on anecdotal tales from other musicians and friends of his from those days, which is a lot like playing a game of telephone. There just isn’t much to go on, and his Johnson’s nomadic nature made it even harder to get a sense of his beginnings.

He’d pester every local musician he could for a chance to share a stage of a jam session with them. Many times, between other musicians’ sets, Robert would take over the stage and play some songs of his own. A bold move for sure. Legendary bluesman Son House knew Robert Johnson during these years, and wasn’t exactly blown away by the young man’s ability at the time:

“Folks they come and say, ‘Why don’t you go out and make that boy put that thing down? He running us crazy,’ ” House said. “Finally he left. He run off from his mother and father, and went over in Arkansas some place or other.”

When he was 18, Robert married sixteen-year-old Virginia Travis, but tragedy struck soon after, as she died during childbirth. Rumors abounded that it was punishment for his burgeoning musician lifestyle, but he forged ahead, deciding to dedicate his life to becoming a bluesman. He did manage to marry again in 1931, at the age of 20, though she too died while giving birth. This set him on an even more solitary path.

Johnson would stay with numerous women, whom he would return to from time to time, but he remained single, adopting different aliases. The women he frequented mostly didn’t know about each other, and he preferred it that way. He was a loner, committed to playing music and travelling the road, playing music at his frequent stops. At his shows he would play mostly crowd-pleasing songs of the time, including jazz and country standards. And even though he would form strong temporary relationships with the townsfolk and local musicians, his stays would be brief, and then he would move on as easily as the breeze.

Birth of the Legend

Son House mentioned that Johnson went to Arkansas for a time, and was somehow very different when he returned to Mississippi. The prevailing thought was that Johnson at the time was a mediocre guitar player, but overnight seemed to have gained an almost supernatural ability at the instrument. That’s where the myth came about that he sold his soul to the devil late one night at a Delta crossroads, in order to become a virtuosic guitarist and songwriter. It’s the only possible explanation, right?

Pop culture has had a long love affair with the idea of a man selling his existence to an evil entity for musical riches. The 1986 film Crossroads had leading man Ralph Macchio on a countrywide quest to learn about the legend of that devilish pact, and to find a lost song that Robert Johnson never got to show to the world. 2000’s O Brother, Where Art Thou saw the trio of prison fugitives led by George Clooney coming across one Tommy Johnson, who, you guessed it, sold his soul to Satan to be able to play the guitar. It’s a fantastical story, and that’s why it’s been told for so long, and in so many mediums. And of course it’s fiction, but why let the truth get in the way of a good story?

What’s more likely is that Robert Johnson practiced tirelessly at home, and at any clubs that would give him an opportunity to play. And he even allegedly admitted to people that during his time away, he had been studying with some kind of guitar teacher. But it seemed like he had taken those lessons to some kind of new heights. His technique was something almost completely new, in which some of his guitar lines mimicked what the bass parts of a piano would play. In fact, many who studied his playing noticed that he did some kind of impressive combination of playing slide, rhythm, and bass all at the same time, while also singing. Playing non-stop is where those chops came from.

Creating A Lasting Impression

Those chops came in handy, as Johnson in 1931 was gaining enough traction to be able to play lots and lots of gigs. For most of the 1930s, Robert Johnson moved from his Mississippi Delta stomping grounds, to Memphis and Arkansas, busking on street corners with his acoustic guitar for tips. When other musicians would offer him gigs, he’d travel to New York, Chicago, and many other cities around the country.

Johnny Shines was one of the musicians he would often share bills with during his touring. Turns out Shines is one of the sole sources of information that we have about Robert Johnson during those years. Shines met Johnson through a mysterious piano player up in Memphis, and even though the two didn’t quite hit it off, eventually a friendship was formed. The two would hit a new town and set up on opposing street corners, playing for tips. They both had a wandering spirit, Shines remembered:

“Robert was a guy, you could wake him up anytime, and he was ready to go. You say ‘Robert I here and train. Let’s catch it,’ and he wouldn’t exchange no words with you. He was ready to go. It didn’t make no difference (where). Just so he was going.”

Every single gathering you could imagine in the American South where you could enjoy music, Johnson and Shines would entertain at. House parties, soul food dinners, even coal yard and sawmills, the two would play music for the people gathered there. They encountered some hairy moments at a stop in Arkansas, where Shines’ cousin got into a shooting match with his father-in-law. Johnson and Shines took that as an omen, and spent a few months in the northern part of the country, near Detroit. But Robert felt the call of the Mississippi Delta deeply, and always returned back home.

Robert Johnson did seek out a more permanent partner in 1936, but this was in the form of making connections so that he could finally lay down some music in the studio. He was eventually paired up with producer Don Law, but it wasn’t a conventional studio they recorded in. It was a hotel in San Antonio. Regardless of the facilities, those three days of recordings would go down as some of the most important sessions ever in the history of blues and rock music. Johnson recorded in a corner of one of the rooms, not because he was shy (as many music historians thought), but to concentrate the sound in one area to maximize the sound of the guitar, which by then Johnson was quite proficient with.

Under the Influence

“Terraplane Blues”, “Come On In My Kitchen”, and “Kind Hearted Woman Blues” were some of the sixteen songs that Johnson laid down, and then another session in Dallas the next year netted several more tunes. Overall, the total output of Robert Johnson’s recording sessions in his life was 29 songs, but that small amount of music influenced everyone from The Rolling Stones, to Muddy Waters, to Led Zeppelin, to Fleetwood Mac.

Almost any artist who worked within blues arrangements (and many who did not) owes some kind of debt of gratitude to the bluesman. “Terraplane Blues” actually became a modest enough hit in his own lifetime, but his legacy wouldn’t grow until long after his passing. Which was imminent.

A Mysterious End

Just a year after his Dallas recordings, Robert Johnson died in Greenwood, Mississippi. No one knows the cause, but he was a mere 27 years old at the time. The public and the press had no idea he had passed away, and it wasn’t until thirty years later that a historian happened upon his death certificate. He was simply found on the side of a country road, with no potential motives or reasons for his passing. Some say it was a jealous husband who murdered him after Johnson flirted with his wife. Other accounts say that he was poisoned.

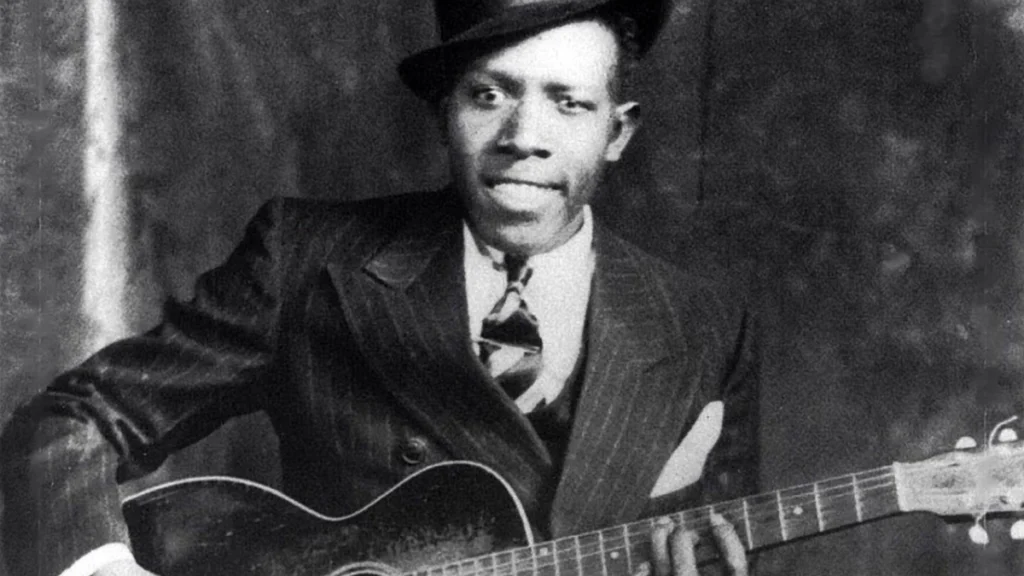

Thomas Gregory – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

In more recent years, some medical professionals floated the theory that it could have been syphilis. In fact, the back of his death certificate has a handwritten note stating the disease as his cause of death. Which, with his proclivity for women, wouldn’t be far out of the realm of possibility. But like so much of his legend, no one really knows how to fill in the gaps. And no one really knows where he’s buried.

The timing of his death could not have been worse. Johnson was just about to be showcased at Carnegie Hall for a monumental tribute concert. His meager success so far with his songs would undoubtedly have skyrocketed after such a high-profile event. Iconic Columbia Records executive John Hammond had Johnson in mind specifically to lend his talents to the event, but sadly it was not to be.

The Legacy

Ironically, decades later, John Hammond would put together the album reissue of Robert Johnson’s songs that would finally make him a household name as a father of blues music. 1961’s King of the Delta Blues Singers might not have made the splash that it did without some serendipitous events. But Hammond took one of those freshly-pressed LPs in 1961 and handed it to Bob Dylan. Dylan was immediately enthralled, and even featured the cover of Johnson’s record on one of his own album covers. Soon after, Johnson’s album would be the barometer of how hip somebody was in the 60s. Eric Clapton would take the torch and run with it too, playing some of his music in Cream and then devoting an entire album to Johnson later in his solo career. Strangely, if white rock musicians hadn’t copped many of his songs when rock music was exploding in the 1960s, we may have never heard of Robert Johnson.

Again, it cannot be overstated just how unknown Robert Johnson was at the time of his death and long after, outside of serious music collectors. Not only was no one really aware of how he died, or where he was interred, but most people just didn’t even know that he was a thing. Until the 1960s, Robert Johnson was on very few peoples’ radar, as far as his talent and the things he contributed to in the music world.

In the 1990s, Johnson’s legacy received another shot in the arm with the release of The Complete Recordings. Which, didn’t the world already have all 29 of his songs? Anyway, the reissue sold a few million copies and won a Grammy award for best historical record, shining a light on his accomplishments all over again.

Some artists wish they could build a body of work over decades, releasing album after album of consistent material. Robert Johnson did that in two recording sessions. A couple of days worth of work that would change the guitar and music in a way that’s still not really credited properly. The fact that he also had devil stories and crossroads and stories of selling souls only enhances his mythos. It’s like a creepy icing on the cake, but it in no way diminishes the quality and urgency of his music. That is plenty devilish by itself.