Of all the Persian kings, Xerxes is probably the one best remembered today thanks to his battle with 300 brave, little Spartans which allowed him to enter the public consciousness.

In a more broader sense, he is known for his invasion of mainland Greece, which went much further than the military campaign of his father, Darius. He saw it as a duty to fulfill his father’s mission of punishing the Athenians for their involvement in the Ionian Revolt. In that regard, he can be considered successful, seeing as he conquered and pillaged Athens, even though Xerxes was, ultimately, unable to retain his control over Greece and had to retreat back to Persia defeated.

His reign also marks the last period of dominance for the Achaemenid Empire. Afterwards, the empire’s power slowly started to fade. Its conquering days were over and most of its efforts were focused on keeping the lands it already had, until the inevitable day when it collapsed completely under the might of Alexander the Great.

Rise to Power

Xerxes (or Khashayar, if you want the Persian name) was born circa 518 BC as the first son of Darius the Great, ruler of the Achaemenid Empire, and his wife, Atossa, who was also the daughter of Cyrus, the man who founded this Persian kingdom. By the way, we have already done Biographics on both Darius and Cyrus. If you haven’t seen them, you might want to check them out to get a better understanding of the Persian Empire, and also because Xerxes’ reign picks up where Darius ended in his fight with the Greeks.

Just to give you a quick recap, ever since the time of Cyrus, the Achaemenid Empire included Greek city-states located not in Greece proper, but on the coast of Asia Minor, modern day Turkey. Oftentimes, these cities were not actually part of the empire, but were ruled by tyrants who were named by and completely subservient to the Persian king. In 499 BC, however, these cities revolted against Darius, with the help of a few mainland Greek city-states, most notably Athens. Eventually, Darius managed to quell the rebellions, but he also swore vengeance on the Greek city-states that provided aid and that is how the first Persian invasion of Greece started in 492 BC.

This invasion ended in defeat. Even though Darius had the early advantage, the Persian expedition failed following a decisive Athenian victory at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC. This did not deter Darius who started planning a second invasion immediately, except that this time he would lead his troops personally, something he was unable to do the first time due to his failing health. His plans were put on hold, though, due to another revolt, this time in Egypt. He intended to deal with both problems, but he died in 486 BC before solving either one, so his successor would have to pick up where he left off.

Obviously, we all know that Xerxes then became the new King of the Achaemenid Empire, but he did have some competition. Strictly speaking, Xerxes was not Darius’s oldest son. He was the oldest son since Darius took power and, more importantly, he was the son of Atossa who had the blood of Cyrus the Great in her veins, but Darius had three other sons by a different wife before he became king. Of them, the oldest was Artabazanes and he argued that, as the eldest child of Darius, he deserved to be king.

Darius himself was not sure what to do and he took council, strangely enough, from a Greek. Not just any Greek, but a former Spartan king named Demaratus who was forced to flee his native land and received asylum in Persia. The Spartan advised Darius, taking the side of Xerxes and arguing that Artobazanes would not have the royal prerogative because, when he was born, both him and his father were still commoners. Darius was in agreement and named Xerxes to be his successor. All of this information comes to us courtesy of, who else, good ol’ Herodotus, and he personally opined that, even without Demaratus’s intervention, Darius was still likely to put Xerxes on the throne due to the power and influence of Atossa.

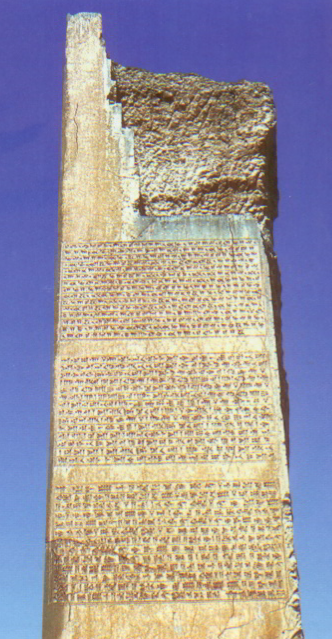

So sometime in late 486 BC, Xerxes became the new king and his ascension went smoothly without any challenges. He then wrote down the facts in a famous inscription to set the record straight:

“Saith Xerxes the king: Other sons of Darius there were, – thus unto Ahuramazda was the desire – Darius my father made me the greatest after himself. When my father Darius went away from the throne, by the will of Ahuramazda I became king on my father’s throne.”

An Undecided King

Now that Xerxes ruled over the Achaemenid Empire, he had important matters to attend to. The Greeks would have to wait, as first, there was the matter of the Egyptian revolt. This did not prove overly difficult. Xerxes already had an army at the ready as his father mustered it in anticipation of going to war against Athens. We do not have too many details about this military campaign, but the Persian king was able to put down the rebellion in a single expedition in 485 BC. He was much harsher with his conquered foes than his predecessors, imposing ruthless punishments on the Egyptians and leaving his brother, Achaemenes, behind to govern the province.

The following year, there was another rebellion, this time in Babylon, led by a man named Bel-shimanni. Again, Xerxes marched his army and put down this uprising in just a matter of weeks. Two years later, in 482 BC, Babylon rebelled once more under Shamash-eriba who declared himself the new king. Although this revolt was also defeated, it proved more durable than the first one and required a months-long siege of the city.

Ancient sources tell us that Xerxes was severe in his punishment of Babylon and ended the special relationship this once-great empire had with the Persians. Up until that point, ever since it had been conquered by Cyrus, Babylon was regarded as one of the Achaemenid Empire’s greatest possessions. The ruler always used the title “King of Babylon” in inscriptions, and the Persian king also took part in Babylonian religious rites every New Year by traveling to the city to take the hands of the statue of Marduk, the Babylonian god, placed inside the city’s main temple, the Esagila.

This all ended under Xerxes. He had the temples pillaged and, allegedly, even removed the statue of Marduk and brought it to Persia to be melted down. Since then, he also no longer used the title of “King of Babylon” in inscriptions, instead referring to himself as the “King of the Persians and the Medes.”

Now that all the internal strife was dealt with, it was finally time to take on the Greeks. Or was it? Classical sources like Herodotus made Xerxes out to be very undecided regarding the path he should take. We cannot say how accurate this portrayal was, but it indicated that the king alternated at least three times between war and peace.

At first, Xerxes wanted war, mainly persuaded by Mardonius, his cousin and one of his closest allies. His arguments were that the Greeks had to be punished for what they did to the Persians, but also that the Greek mainland had rich and beautiful lands “worthy of no mortal master but the king.”

Decided, Xerxes held an assembly with all his nobles and told them of his plans. He said:

“For myself, ever since I came to this throne, I have taken thought how best I shall not fall short in this honourable place of those that went before me… and my thought persuades me, that we may win not only renown, but a land neither less nor worse, but more fertile, than that which we now possess… For this cause I have now summoned you together, that I may impart to you my purpose. It is my intent to bridge the Hellespont and lead my army through Europe to Hellas, that I may punish the Athenians for what they have done to the Persians and to my father… He is dead, and it was not granted him to punish them; and I, on his and all the Persians’ behalf, will never rest till I have taken and burnt Athens, for the unprovoked wrong that its people did to my father and me.”

Mardonius again spoke up to applaud his king’s decision. The other noblemen were quiet, except for an uncle of Xerxes named Artabanus who advised him to reconsider. Years prior, Artabanus told Darius the same thing when he wanted to go to war against the Scythians, and now Xerxes wanted to do the same against a much more powerful foe, an army made up of “the most doughty warriors by sea and land.” The king was greatly angered by Artabanus, saying that it was only because he was his father’s brother that he escaped punishment for his insolence.

It seemed that Xerxes had made his decision, but that night he had a vision which caused him to change his mind, and the next day claimed he would not march against Greece and, instead, would “abide in peace.” But then the next night he had another vision which offered Xerxes a prophecy, saying that if he did not lead his armies, the things that made him “great and mighty” would disappear and he would “be brought low again.” This vision so greatly frightened the Persian king that he went to his uncle, Artabanus, to tell him about it and then ask him to wear the royal robes and sleep in the royal bed. The advisor did so and the same prophetic dream came to him, warning again of terrible things that would befall Xerxes if he did not go to war. And so, finally, Artabanus himself changed his mind and, from then on, the Persian king became intent on invading and conquering Greece.

The Invasion Starts

Even though Xerxes had finally made up his mind, he did not charge headfirst into battle. Instead, he spent years in preparation. The initial challenge was simply getting to Greece in one piece. First, the army had to cross from Asia into Thrace by traversing the Dardanelles Strait, known back then as the Hellespont. According to Herodotus, Xerxes had the Egyptians and Phoenicians build two bridges that connected Sardis, the former capital of Lydia, to another city named Abydos on the other side of the strait. However, those bridges were broken and swept away by a furious storm. So great was the anger of the king when he found out that he not only had the builders executed, but also ordered his men to give 300 whip lashes to the Hellespont itself and drop a pair of manacles into the water to symbolize that even the sea itself must obey the will of Xerxes. Afterwards, he had two pontoon bridges built which proved to be sturdier and more reliable and, in 480 BC, the Persians crossed the strait into Europe.

In Thrace, the army went two ways – part by land and part by sea. However, Xerxes was careful to avoid a lethal mistake made by one of his father’s generals during the first invasion of Greece. Athos was not a large peninsula, but the waters around it were treacherous so, when the fleet went around it, it was caught in a storm and destroyed. To avoid having the same thing happen to him, Xerxes ordered his men to build a canal through the isthmus that connected the peninsula to the mainland. Obviously, over the course of millennia, the Xerxes Canal was completely buried in sediment, but it was actually found recently using aerial photography. It remains one of the few traces of the Persian invasion on European soil, but it also serves as a nice reminder that Herodotus occasionally knew what he was talking about.

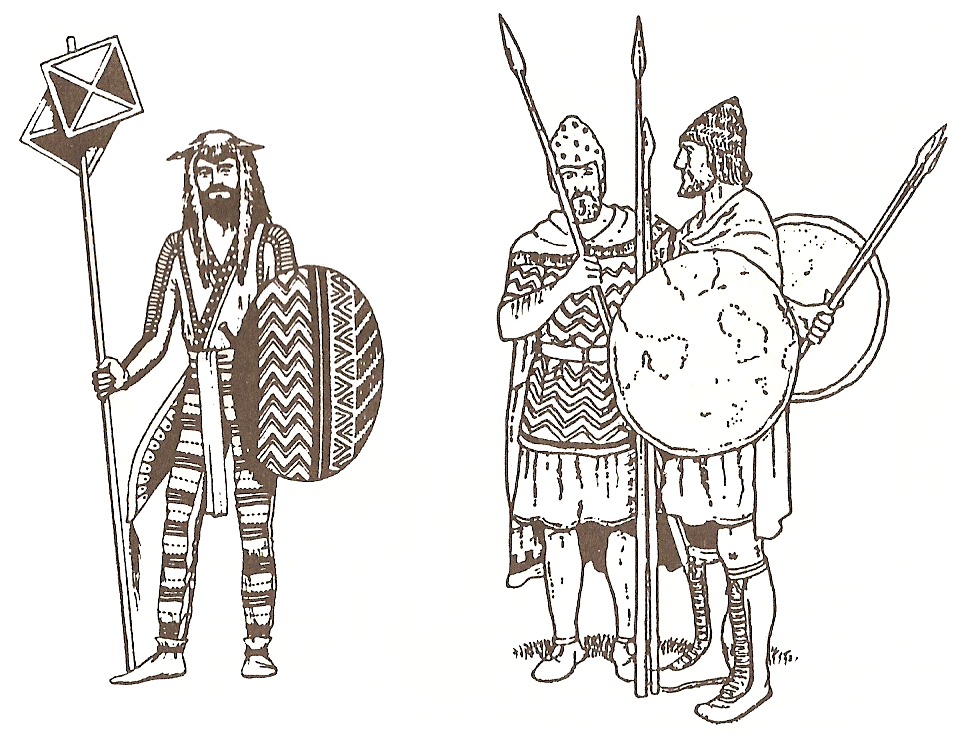

Speaking of Herodotus, the historian claimed that the army assembled by Xerxes was the largest in existence, unlike anything the world had seen before. It contained soldiers from all over Asia, of 30 different ethnicities, and that did not take into account the numerous Thracian tribes that Xerxes encountered on his way to Greece which were added to his numbers, either willingly or by force. However, we cannot provide you with an accurate figure as the size of the army is still hotly debated and the estimates are all over the place, from a few hundred thousand soldiers as proposed by modern scholars to a few million based on ancient sources.

Either way, this was an army that no Greek city-state hoped to take on alone. The Greeks, however, had not been dawdling this whole time. Ever since they repelled the first Persian invasion under Darius, they knew it was only a matter of time before a new one would come. The Athenians, in particular, who were Xerxes’ main target, had been busy building up their fleet for an unrelated war with another city-state named Aegina. However, in 481 BC, when they heard that the Persian army was on the move, dozens of Greek city-states held a council in Corinth and agreed to put aside all their feuds and deal with this major threat. Many other city-states wanted no part of it and instead paid tribute to Xerxes when he sent forth ambassadors asking for “earth and water,” hoping that his issues with Greece would not involve them. Only two city-states were never given this option because Xerxes omitted them from the start. Those states were Athens and Sparta.

This Is Sparta

Halfway through 480 BC, Xerxes had his first major encounter and this is the famous one that everybody has heard about – the Battle of Thermopylae, where 300 Spartans led by King Leonidas staged a daring last stand, fighting bravely to guard the coastal pass of Thermopylae, also called the “Hot Gates.” In the end, the vastly superior numbers of the Persian army proved too much to overcome and all the Spartans fell in battle.

If you are familiar with this event, it’s probably because of the movie 300, or the comic book series it was based on. However, those two helped create a few prevalent myths about the Battle of Thermopylae, and we’re not just talking about showing Xerxes as a seven-foot-tall giant with a thing for gold piercings. Undoubtedly, the biggest myth is that the 300 Spartans were there alone. In fact, they weren’t; not even close. The Spartans might have been in charge of the defense, but they were joined by about a dozen other Greek groups, including Thespians, Thebans, Arcadians, and Phocians. In total, there were around 6,000 to 7,000 Greeks at the Battle of Thermopylae. As for the Persians, we don’t know. A lot more than that, definitely, as Herodotus claims that just their casualties numbered 20,000 men.

A crucial role in the battle was played by Ephialtes (or Epialtes, in classical sources), the Spartan who betrayed his people and told Xerxes of a secret trail that allowed his soldiers to flank the enemy. He was actually real, but he was not a deformed Spartan who resented his compatriots because he could not fight alongside them. He wasn’t a Spartan at all, in fact, he was part of a Greek group called the Malians, who lived in the city-state of Trachis.

Lastly, a lot of sources mythologized this battle and portrayed the Greeks as willingly undertaking a suicide mission where they knew from the start that they had no chance of winning. Again, this is not true. If there were truly only 300 Spartans, maybe, but it would have made absolutely no sense to sacrifice a whole army of 7,000 soldiers for no reason. This is evidenced by the fact that, once the Greeks realized that the Persians were flanking them, most of their remaining forces retreated. That is when Leonidas and his Spartans decided to stay behind and form a rearguard in order to give everyone else time to escape. They still were not alone, though. The Thespians and the Phocians also stayed behind to fight, so they deserve some credit, too. The Thebans also stayed, but they eventually surrendered.

Finally, while this is not a myth, it is an important aspect that often is forgotten. While the land battle at Thermopylae was going on, the Greeks and the Persians were simultaneously engaged in an important naval conflict known as the Battle of Artemisium. The bulk of the Greek forces was provided by Athens since they had the strongest fleet, aided by Corinth, Megara, Aegina, Chalcis, Sparta, and others. This battle was not a crushing defeat for the Greeks like Thermopylae, but they still were unable to stop the advance of the Persians. Following these two encounters, Xerxes had gained control over the regions of Euboea, Boeotia, and Phocis, and, most importantly, he had a clear route to Attica, where Athens was located.

In September 480 BC, Xerxes entered Athens. The city had been mostly abandoned, with Athenians fleeing to Aegina and Salamis. Just a few remained to try and protect the Acropolis, but they were easily defeated. Xerxes was finally able to fulfill the vow first made by his father to punish the Athenians for their interference in the Ionian Revolt almost two decades prior. He had the city burned and pillaged. Athenian symbols like the Parthenon and the Temple of Athena were razed to the ground, although these would be rebuilt a few decades later by Pericles, bigger and better than ever.

The Tide Turns

So far, everything seemed to go in Xerxes’ favor. All the remaining Greek forces had gathered on the Peloponnesian Peninsula in the south of Greece, which, on foot, could only have been accessed by crossing the narrow Isthmus of Corinth. However, the Greeks took steps to ensure this would not happen as they destroyed the only road and erected a wall in its place. If Xerxes were to continue his conquest of Greece, he would have to do it by water.

Strategically, it would have been wiser to wait out the Greeks by creating a blockade to surround their navy concentrated around Salamis and to allow each group of people to slowly disband and return to their own cities. In fact, one of the Persian king’s allies, Queen Artemisia of Caria, advised him to do just this. However, his other generals and, indeed, Xerxes himself, were sure of victory with one giant show of force at sea. After all, his fleet was bigger, consisted of better ships, and had the tactical advantage.

The Battle of Salamis took place sometime in late September 480 BC and it was a shocking and brutal defeat for the Persians that completely turned the tide of the campaign in favor of the Greeks. Unfortunately, none of the classical sources gave a detailed account of the battle so we don’t know what bold and brilliant military strategies the Greeks employed to secure this unlikely victory. Herodotus mainly credits his countrymen for being orderly and determined while the Persian army was much more chaotic and disorganized which he sees as the “reason that they should come to such an end as befell them.” To illustrate his point, he tells the story of the aforementioned Artemisia who, while being chased by an Athenian trireme, rammed and destroyed a friendly ship to convince her pursuers that she was on their side. The vessel she sank had onboard Damasithynus, the King of Calyndus, who died in the water.

Another early casualty at the start of the battle was Ariabignes, a brother of Xerxes and the admiral leading the Phoenician fleet, whose death caused a lot of panic and loss of morale among the Persian navy.

Diodorus gives a lot of credit to the Athenians for the role they played in the victory, which is not surprising considering they accounted for over half of the entire Greek fleet. Also noteworthy were the Megarians and the Aeginetans, who were considered the best seamen after the Athenians and alone formed the right wing of the Greek forces. The location of the battle also played an important role. The passage inside the Strait of Salamis was too narrow for the advancing Persian line which had to withdraw ships and reorganize mid-battle, thus leading to the general chaos and confusion which ended in their downfall.

This shocking upset forced Xerxes to completely reconsider his next move. He did not want to spend the winter in Greece, and then another season campaigning while neglecting the rest of his empire. He also feared that the Greek navy might make its way up north and destroy the bridges he had built across the Hellespont, thus trapping his land army in Europe. Therefore, he decided to take a large part of his army and make his way home, leaving his elite infantry and his cavalry behind under the command of his general Mardonius to keep the pressure on in mainland Greece.

This strategy did not end well for the Persians. After winter passed, they were on the warpath again, but so were the Greeks who had time to reorganize and strengthen their forces. The Greek army mainly consisted of Spartans, Athenians, and Corinthians, although over a dozen other cities also contributed soldiers. The two sides met at the Battle of Plataea sometime during the summer of 479 BC. Again, it was a triumphant victory for the Greeks, decisive enough that it drove the Persians away from the Greek mainland.

At the same time, the Greek fleet made its way to Asia Minor to execute a preemptive strike on the remaining Persian navy stationed there. Instead of a naval battle, the Persians coerced the Greeks into coming on land, but this tactic was in vain. At the Battle of Mycale, the Greeks delivered a final crushing blow to their opponents, effectively ending the Persian invasion. Afterwards, the Spartans and the rest of the Peloponnese sailed home, considering their mission a success. The Athenians and other city-states pressed on with a counterattack to liberate the Greeks in Ionia, as well.

Final Years

It’s hard to tell how Xerxes perceived his military campaign in Greece. Obviously, it didn’t end like he wanted, but he did accomplish his stated goal which was to punish Athens. It would have been possible for him to rebuild his army and try again in a few years but, from that point on, he seemed more concerned with internal matters, ensuring that he maintained control over his possessions in the Middle East and Northern Africa.

He also became a prolific builder during this time, mainly in Persepolis and Susa. He completed unfinished projects of his father and started his own. The Apadana, the Gate of All Nations, the Tachara Palace; the citadel, the gardens, and the canals of Persepolis were all finished during the 15 years that followed.

Xerxes did have one last attempt in 466 BC when he tried to regain control over the Ionian states in Asia Minor. If he had succeeded, he would have likely considered a third invasion, but he was defeated at the Battle of the Eurymedon by a Greek alliance known as the Delian League and he gave up whatever plans he might have had.

Even if he did intend on a new invasion, he would not have had the opportunity to go through with it because he was assassinated the following year. In 465 BC, both Xerxes and his heir, Crown Prince Darius, were killed by an official named Artabanus. The circumstances are somewhat unclear, though. Some sources say that the politician first killed Darius and, fearing the wrath of Xerxes, arranged for the king’s death, as well. Others say that Artabanus first had Xerxes killed and made it look like Darius was responsible and got him executed. Either way, the king’s other son, Artaxerxes, ascended to the throne of Persia and, upon discovering the treachery of Artabanus, had him and his sons all executed.