During the 1910s, Hollywood, California, established itself as the new and undisputed Mecca of the budding film industry. Already, its movies were hits throughout the US and its stars were some of the most famous and glamorous people in the country, placed by the public on a pedestal above us mere mortals.

The 1920s were a different matter, though, as several controversies began to take some of the shine off Hollywood to reveal the grime underneath. The decade started with the suspicious death of actress Olive Thomas, who had a tumultuous marriage to actor Jack Pickford. Then, in 1921, the death of Virginia Rappe at a party hosted by larger-than-life comedian Fatty Arbuckle, who then stood trial for her murder, became the biggest scandal in the nation. The tabloids eagerly fanned the flames of controversy, looking to milk that story dry, but if you want to get the full picture, we already covered Fatty Arbuckle here on Biographics.

Anyway, Hollywood was still reeling from the Arbuckle affair when it got hit by another scandal – the murder of director William Desmond Taylor. Once again, the newspapers had a field day with the salacious details uncovered in the investigation – a fake identity, compromising photographs, a drug and sex-filled party life, a secret family, an underage love affair, a vengeful mother; the story had it all. And that, of course, was without taking into account the actual killing of William Desmond Taylor, which involved several Hollywood stars and remains an unsolved murder to this day.

Early Years

William Desmond Taylor was born William Cunningham Deane-Tanner on April 26, 1872, in Carlow, County Carlow, Ireland. He was one of five children of Thomas Kearns Deane-Tanner and Jane O’Brien and grew up on quite a lavish estate in the Irish countryside. His family wasn’t among the movers and shakers, but they were definitely well-off. Jane O’Brien had inherited plenty of land from her own father, while Thomas Deane-Tanner was a retired major with the British Army.

The senior Deane-Tanner expected William to follow in his footsteps and embrace the army life, but even from a young age, the boy was more interested in the performing arts. His father would hear none of it, though, and he sent William to Clifton College in Bristol where he studied engineering. However, being away from the family farm also granted William a modicum of independence. Soon after he turned 18, he took a trip to Manchester, where he saw a famous stage actor of that time, Charles Hawtrey, perform in his biggest hit, a farcical play dubbed The Private Secretary.

William became so enraptured by the performance that he decided this was the life he wanted to pursue. After the show, he plucked up the courage to approach Hawtrey and ask him for a job on his production. William claimed he had “lots of experience” – an obvious lie, but maybe he caught Hawtrey in a good mood. Or maybe the veteran actor saw something in the boy. Either way, he gave William a small part in the show.

This was Taylor’s big break in the entertainment business, but it didn’t last. During one production of The Private Secretary in London, some of his family acquaintances were in attendance. They recognized William and promptly called his father to inform him of his son’s new career choice. Suffice to say that Thomas Deane-Tanner was not pleased. He summoned his son back home and decided that he needed to go someplace far, far away from the temptation of the stage. And just like that, in 1891, William found himself transported from the hustle and bustle of London to a farm in the middle of nowhere…in Harper, Kansas.

We’re not sure exactly what the plan was. Did William’s father hope that some time away would get rid of his artistic fancies, or did he renounce his son completely? Either way, William’s passion did not dim in the slightest. He worked for a few years as a farmer. Then, when the Klondike gold rush came in, he traveled to Alaska where he became a miner, putting that engineering background to good use. But during all these years, he still found time to act, taking to the stage in-between farming and mining seasons. Once again, he met someone who understood his potential. This time, it was stage actress Fanny Davenport, and she gave him roles in many of the plays that she starred in.

Davenport died in 1898, at which point William decided to travel the country for a bit, eventually ending up in New York City. There, he met an actress named Ethel May Harrison, and the two of them married in 1901 and had a daughter named Ethel Daisy.

William’s new father-in-law was a wealthy Wall Street broker who got him a job managing a fancy antique furniture store on Fifth Avenue. More than that, his connections and reputation instantly elevated William and his family into a higher class of society, aided by William himself who made quite a bit of money while mining in Alaska. In other words, this could have been his new life – that of a successful businessman among New York’s upper class – but it still wasn’t the life that he wanted. The call of the limelight proved to be overpowering once again so, in 1908, William simply disappeared. He took off, leaving his family behind, and when he finally reemerged, he was not William Cunningham Deane-Tanner anymore, he was William Desmond Taylor.

Hollywood, Here I Am

The years immediately following Taylor’s disappearance are a bit of a blank. Some say that he went with the most obvious choice and resumed his acting career, while others claim he traveled north to the Yukon and worked as a miner again. Around 1912, however, he finally emerged in California, under his new name, looking to take his acting from the stage to the silver screen.

Remember that Hollywood was just beginning to emerge as the hip, new place to make a movie. Other locations like New York City and Fort Lee, New Jersey, were where the American film industry was born, but many movie companies were already looking to move to the West Coast, and if you want to know why, it had a lot to do with Thomas Edison. The inventor held patents on a lot of technology relevant to moviemaking and he tried to monopolize the industry by making sure that nobody could make or show a film without him getting a cut. Those who tried were sued and had their equipment confiscated, so it’s not too surprising that production companies sought greener pastures. Therefore, they moved to the opposite end of the country as a middle finger to Edison, whose influence didn’t quite reach that far. By 1910, companies like Biograph and Selig Polyscope opened the first movie studios in Los Angeles, and they were quickly followed by many others.

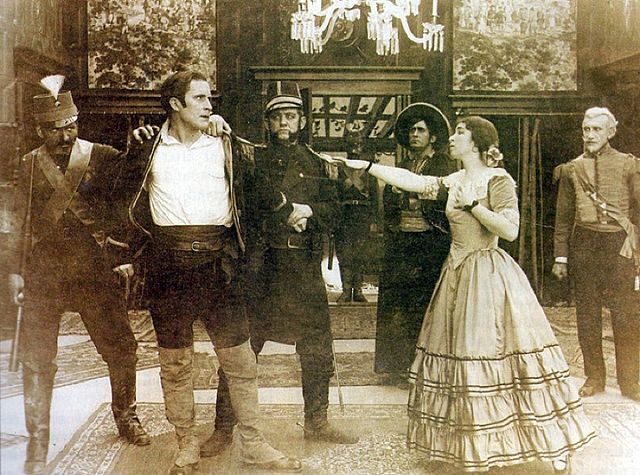

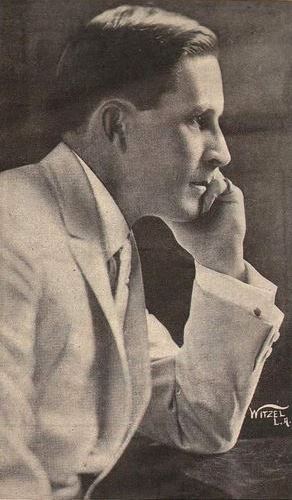

Among these was the New York Motion Picture Company, which gave William Desmond Taylor his first role in December 1912, in a movie titled The Counterfeiter. This was followed by several other roles in 1913 for the same company until Taylor switched to Vitagraph, where he began filming westerns. His biggest hit at this time was a drama titled Captain Alvarez, where Taylor played the lead role. Apparently, Taylor developed a reputation of treating everyone the same, both stars and extras, and was so well-liked on the set that the people who worked with him all chipped in and got him a snazzy leather portfolio as a gift, with the inscription “To William Taylor, actor, good fellow, and gentleman who will always be thought of by the undersigned as ‘Captain Alvarez.’”

It was only when this movie came out that Taylor’s wife finally found out what had happened to him when she saw him on the big screen. By that point, Ethel May had legally divorced him in absentia, but she contacted him in Hollywood and the couple reconciled somewhat. They never got back together – Taylor was engaged to actress Neva Gerber until 1919 – but he did visit his family every now and then and made his daughter his legal heir. In return, his ex-wife kept this shameful episode of Taylor’s life a secret from the public.

Sitting in the Director’s Chair

After Vitagraph, Taylor worked with Balboa Studios based in Long Beach, California. This was an important step in his career because Balboa allowed Taylor to direct his first movie and, as much as he loved being on stage, he soon discovered that he preferred to be behind the camera. From then on, Taylor only took a handful of small acting roles before making the switch permanently to directing. He worked with multiple companies such as Pallas Pictures, the American Film Company, and Fox Films, until 1917 when William Desmond Taylor joined Famous Players-Lasky, the precursor to Paramount Pictures, and stayed with them for the remainder of his career.

Taylor directed almost 60 movies, although most of them are lost today. He worked with many popular stars of the silent era, including Mary Pickford, Wallace Beery, and Wallace Reid, but of particular note was Mary Miles Minter who would later find herself in the middle of the scandal surrounding Taylor’s murder.

In early 1918, Taylor directed Mary Pickford in a movie titled Johanna Enlists, a comedy where the protagonist falls in love with a soldier. It was one of many films made around this time that showcased the admirable qualities of the men fighting in World War I, which were used both as morale boosters and as recruitment tools. This particular movie had the desired effect on at least one person because after he finished shooting it, William Taylor took a little vacation, and then he enlisted in the British Army.

In August 1918, Taylor arrived at Camp Ford Edward in Nova Scotia, Canada, as a private with the Royal Fusiliers of the British Army. Once again, Taylor proved incredibly popular with the people around him, as his NCOs described him as “a fine fellow”, “a gentleman in every sense of the word”, and “a man who never thought of himself, who was always helping the underdog.” That being said, Taylor might have had a slightly-glamorized image of military life, as he arrived at camp wearing several diamonds and packing a wardrobe full of fine, expensive clothing, which he then had to send back to Los Angeles.

Ultimately though, Taylor got the hang of things, and his ability to learn quickly, his willingness to follow orders without comment, and his popularity with the other men ensured that he rose through the ranks quickly. He was made a corporal within three weeks of his arrival at camp, then a sergeant and, finally, a sergeant major in two months. By the time Taylor was actually sent to England, he had a lieutenant’s commission. And let’s not kid ourselves. No matter how likable the guy was, this was all because he was a famous movie director, not because he was some kind of military mastermind.

We don’t think Taylor actually saw any action. He was placed in a non-fighting unit and stationed at Dunkirk with the Army Service Corps of the Expeditionary Forces Canteen Service, but after the armistice. In May 1919, Taylor returned to Los Angeles and was honored with a Homecoming Victory Dinner by the Motion Picture Directors’ Association. He resumed his movie career and scored two of his biggest hits when he directed the screen adaptations of two popular books of the day, Anne of the Green Gables and Huckleberry Finn. Everything seemed to be going his way, but not for long…

Murder Most Foul

On the morning of February 2, 1922, Taylor’s valet, Henry Peavey, entered the living room, only to find his employer lying on the floor. The valet tried waking him, but it soon became clear that Taylor was dead. No wounds or injuries were readily apparent, which made Peavey think that the director had died of natural causes, two months shy of his 50th birthday. This might explain why some of Taylor’s acquaintances were told of his death before the police. Allegedly, the cops were only notified 12 hours after the crime, and, when they finally showed up at Taylor’s bungalow in the affluent Westlake neighborhood of Los Angeles, they found execs from Famous Players-Lasky burning documents in the fireplace, while actress Mabel Normand was frantically searching through Taylor’s office, looking for incriminating photographs. We say “allegedly” because everything that happened from now on has been tainted by rumors, gossip, and media speculation that make it almost impossible to separate facts from fiction.

Anyway, the cops inspected Taylor’s body and when they turned it over, they saw that the director didn’t die of natural causes, after all. He had been shot. Obviously, this changed the complexion of the case. The police wanted to reconstruct William Desmond Taylor’s final hours and assemble a list of people who might have wanted him dead. His friends and colleagues were terrified of the negative publicity that this would generate. Meanwhile, William Randolph Hearst and his ilk were salivating at the idea that they had another Hollywood scandal on their hands to fill their pages, even though the Fatty Arbuckle trials weren’t even over yet. Almost immediately, newshounds discovered that William Desmond Taylor was actually William Cunningham Deane-Tanner and that he had a secret family that he abandoned years ago. Already, the story was getting juicy, but it was just getting started.

According to the timeline established by the police, Mabel Normand would have been the last person to see Taylor alive, other than his killer, of course. She arrived at his home on the night of February 1 at around 7 pm and stayed less than an hour. When she left, both were in good spirits, and Normand’s car drove away while the two of them blew kisses at each other. It seems that Taylor was slain just minutes later, at around 8 pm, as several neighbors heard a noise that sounded like a car backfiring, but was most likely the gunshot that killed the director. Faith MacLean, the wife of actor Douglas MacLean, said she looked out the window and saw a dark figure wearing a long coat walking out of the house. She assumed it was a man, but the person had their collar up, a cap over their face, and had an “effeminate walk,” so it could have also been a woman.

Who Did It & Why?

Right away, investigators thought that the butler did it. A bit of a cliché, perhaps, but the police were willing to overlook this small detail if it closed the case. Not the current butler, mind you, Henry Peavey, but Taylor’s former butler, Edward Sands, who got sacked in 1921 for stealing from his employer and forging checks in his name. A bit of looking into his past revealed that Sands was just an alias and that his real name was Snyder and he had a history of petty crimes. Sands had also broken into Taylor’s home after being fired to steal some more, so he knew how to gain access. However, he disappeared after the murder and he was never seen again. At one point, someone claiming to be Sands wrote to the Los Angeles District Attorney, Thomas Woolwine, and offered evidence that would clear him of the crime and name the true killer, if all the other charges against him were dropped. However, this person never followed up on the offer, so the true fate of Edward Sands is still a mystery, although he remains the favorite suspect of many.

Taylor’s current butler, Henry Peavey, was also briefly a suspect because he was the one who discovered the body. The police cleared him pretty quickly, however, but it seems that their efforts were not good enough for the office of the Los Angeles Examiner, which became convinced that Peavey was the culprit and went to insane lengths to try and prove it. Seriously, if we didn’t have the statement from the District Attorney, this would have been almost unbelievable. First, a couple of reporters from the Examiner showed up at the house and pretended to be police officers from New York and asked Peavey to accompany them to the newspaper’s offices to answer some questions. When he said “no,” they offered him $1,000 and that got him moving. At the building, they kept Peavey in a locked office for 12 hours, basically holding him hostage. When they finally released him at night, they only gave him $10 and, instead of taking him home, they drove him to the cemetery where Taylor was buried.

Basically, their premise was this – because Henry Peavey was an uneducated Black man, the reporters thought that they could scare a confession out of him. They took a walk through the cemetery, talking about spiritualists and ghosts to set the mood, at which point another man wearing a white sheet appeared, claiming to be the spirit of William Taylor and urging the butler to confess to his murder. Their foolproof, Scooby-Doo plot didn’t work because 1. Henry Peavey wasn’t superstitious; 2. He wasn’t an idiot; and 3. He seemed to be the only person there aware that the real Taylor spoke with a British accent, unlike the “ghost” who sounded like a gangster off the streets of Chicago.

DA Woolwine later denounced the Examiner in a statement that said:

“Henry Peavey…was taken from his room by a pair of conscienceless blackguards who represented themselves to be officers of the law, and held a prisoner from noon until about midnight on last Sunday. During this imprisonment, he was subjected to the most outrageous treatment. He was held for hours in the office of the Los Angeles Examiner, not even being permitted to leave the premises to get necessary food when he became hungry…

To add to the unspeakable injustice of this high-handed procedure, he was conveyed to the cemetery by night by these two scoundrels, who first took him from his room, and another rascal who joined them, was taken to the tomb of his former employer and every effort made to bully and terrorize him…

I feel it my duty as District Attorney of Los Angeles County, to expose such vile, cowardly and unlawful practices, for the perpetrators of which every decent citizen should feel a most supreme and utter contempt.”

Although not as unique and exciting as the Peavey incident, another possible scenario involved Mabel Normand. The exact nature of the relationship between Taylor and Normand remains up for debate due to media rumors and speculation, but it ran the gamut from one extreme to another. Some said that Taylor was a closeted gay man and that his relationship with Normand was purely platonic and an attempt by the movie studio to hide his sexual orientation. Others went in the opposite direction and accused the director of being a serial womanizer who often took pornographic photographs of his liaisons and kept a collection of monogrammed women’s lingerie as mementos of his conquests.

Either way, two things were for certain. One – the two of them were madly fond of each other, even if they were just friends. And two – Mabel Normand had a coke habit. Taylor tried to help her get treatment several times, without success, and eventually, he thought that the situation called for more drastic action, by turning in her dealers to the police. Unfortunately for him, they found out about his plan and they weren’t too pleased. The quick in-and-out without leaving evidence, the single fatal shot – these all suggest that the murder could have been a professional hit, in which case, the perpetrator could have been someone looking to silence the director and protect their racket.

But even more outrageous than a murderous drug ring was the relationship between William Desmond Taylor and actress Mary Miles Minter…and her mother. Minter was a former child star who was 30 years younger than Taylor and became the director’s protégé. When the police discovered that Minter had written Taylor several love letters, the new salacious story in the headlines was that the two were having an affair that began when Minter was 17 years old. The girl’s mother, Charlotte Shelby, was a failed actress who lived vicariously through her two daughters and exerted a domineering control over their careers. Therefore, when she found out about the relationship, she feared that it could ruin Mary’s acting career, so she took matters into her own hands and gunned down William Taylor.

It is a pretty convincing story, but the only thing that we can say with a fair degree of certainty was that the young and impressionable Mary Miles Minter fell in love with her mentor. There was never any hard evidence that he reciprocated her feelings. As far as Charlotte Shelby was concerned, she had an alibi…ish – a man named Carl Stockdale claimed he was with her at the time of the murder, and that the two played cards between 7:30 and 9:30 pm. Even so, she remains, to this day, the favored suspect of many people who believe that Charlotte Shelby simply bought her alibi. Ever her own daughters accused her of the crime – Mary Minter made ambiguous allusions, but her sister, Margaret Shelby, also an actress, outright said that her mother killed William Taylor. However, both sisters hated their mother, so despite a Grand Jury inquiry into Charlotte Shelby’s guilt, a conclusion was reached that there was insufficient evidence for an indictment.

These are just the major suspects. There were many others. A Connecticut man describing himself as “an avenging husband” wrote a letter confessing to killing Taylor for having an affair and later “scorning” his wife. In 1964, an actress named Margaret Gibson confessed on her deathbed to doing the deed, as well. Some rumors claimed the killer was an old rival of Taylor’s from his Klondike Gold Rush days. Others said that it was a Canadian soldier who bore a grudge against the director from World War I. Even the IRA and the Ku Klux Klan were suspected by some.

But alas, many were named, many even confessed, but none were ever convicted. Alongside the Fatty Arbuckle trials and a couple of other scandals, the murder of William Desmond Taylor became a rallying point against Hollywood for those who decried its licentiousness and called it the “American Sodom and Gomorrah.” In a bid to survive, the movie industry decided to police itself and enacted the Hays Code, which went on to shape Hollywood up until the late 1960s, while skeletons such as Taylor’s murder were locked in the closet and forcefully forgotten.