During the 1950s, James Clavell was a scriptwriter trying to make it in Hollywood. Then, in 1960, the Writers Guild of America went on strike, so, unable to work on any new scripts, he began writing a novel. Back in World War II, Clavell had served in the Pacific Theater and was even a Japanese POW for a while, so he opted to use that setting for his novel. The result was King Rat, a book that came out in 1962 and sold pretty well.

Bolstered by his success, Clavell kept writing novels set in Asia in different periods, with Westerners as the protagonists. The second novel, Tai-Pan, did even better than the first, but it was the third one that became a worldwide sensation. Titled Shōgun, it told the story of a 16th-century English navigator named John Blackthorne who washed up on the shores of Japan during a time of great crisis, when multiple warlords were vying for power. Blackthorne, of course, finds himself trapped in the middle of this brouhaha, helps one of the lords defeat his enemies, and, as a reward, ultimately, becomes the first English samurai in history.

It was quite a tale, but it did not entirely come from the mind of James Clavell. In fact, he based the story of John Blackthorne on the real life of William Adams.

Early Years

William Adams was born in September 1564 in Gillingham, Kent, not too far from London. We don’t know anything about his family or his childhood other than the fact that he had a younger brother named Thomas. The few tidbits we have from this period of his life come from letters Adams wrote while in Japan. When he was 12, Adams traveled to East London to apprentice to a master shipbuilder named Nicholas Diggins. He spent 12 years there. During that time, Adams learned navigation, astronomy, and shipbuilding, useful skills that would later make him such a valuable resource to the Japanese shogun.

In 1588, England was at war with Spain, so Adams left to serve. That was the year Spain tried to invade using the feared Spanish Armada, only to be defeated and lose half the fleet. During that time, William Adams served as captain of the Richard Duffield, a supply ship that ensured the main fighting force was stocked with food and ammo. We don’t know if he saw any actual combat during the war.

Obviously, with all those years spent apprenticing, Adams had prepared himself for a life at sea. So after the Armada had been routed, he made a quick trip ashore to get married to a woman named Mary Hyn, and then it was off to sail the seven seas. He found a job with the Barbary Company, a trading venture between England and Morocco. He did this for five years or so, but it’s hard to be accurate since Adams never wrote about this period of his life.

Around the mid-1590s, Adams switched to serving aboard Dutch ships, which wasn’t particularly surprising since England and the newly formed Dutch Republic were allies at the time – England helped the Dutch rebel against the Spanish Crown, and, in turn, the Dutch helped the English fight off the Spanish Armada.

There is some talk that Adams spent a few years with a failed Dutch expedition to find the Northeast Passage, but this comes from uncertain sources, while Adams himself stayed mum on the subject. But we can talk about his following expedition because that was the voyage that cemented his legacy.

From Gillingham to Japan

In 1598, William Adams was part of a five-ship Dutch fleet headed for the Pacific. Originally, he was supposed to be the pilot of the Hoop, meaning Hope, before he got transferred to the Liefde, meaning Love. This turned out to be a huge blessing in disguise for Adams, since the Hoop was lost at sea with all its crew, while the Liefde became the only ship of the fleet that made it to Japan. But even before all of that, the fleet ran into plenty of trouble on the way.

The ships left Holland on June 24, 1598, with 750 men aboard. They got delayed for weeks in Cape Verde as many of the crewmen fell ill with scurvy and dysentery, including the fleet commander, Jacques Mahu, who died in September while they were still sailing off the coast of Africa. Simon de Cordes took over leadership of the expedition, and with him at the helm, the fleet crossed the Atlantic and headed for South America, intending to cross the Straits of Magellan into the Pacific Ocean.

They reached the straits in April 1599, but unfavorable winds forced them to wait four months. During that time, many men died either of exposure or violent encounters with the natives. Somewhat surprisingly, the actual crossing of the straits went smoothly; a first for the trip. But as soon as they were on the other side, things quickly went sideways again. They encountered the biggest storm so far, and two of the ships were blown off-course. One of them headed for the East Indies and got captured by the Portuguese, while the other one, the Geloof aka the Faith, went full-on Cartman mode and said “Screw you guys, I’m going home.” It then sailed back through the Straits of Magellan and returned to Holland. It was the only vessel of the fleet to make it back, which it did with only 36 crewmen out of over 100.

A third ship was captured by the Spanish near Chile, and that only left the Liefde and the Hoop. The Liefde also had a perilous encounter in Chile when they were attacked by the locals. This assault was described by Adams:

“The next day, being the 9th of November 1599, our captain, with all our officers, prepared to go a land, having taken counsel to go to the water side, but not to land more than two or three at the most; for there were people in abundance unknown to us: wild, therefore not to be trusted; which counsel being concluded upon, the captain himself did go in one of our boats, with all the force that we could make; and being by the shore side, the people of the country made signs that they should come a land; but that did not well like our captain. In the end, the people not coming near unto our boats, our captain, with the rest, resolved to land, contrary to that which was concluded aboard our ship, before their going a land. At length, three and twenty men landed with muskets, and marched up towards four or five houses, and when they were about a musket shot from the boats, more than a thousand [natives], which lay in ambush, immediately fell upon our men with such weapons as they had, and slew them all to our knowledge. So our boats did long wait to see if any of them did come again; but being all slain, our boats returned: which sorrowful news of all our men’s deaths was very much lamented of us all; for we had scarce so many men left as could wind up our anchor.”

This was a great blow for the crew of the Liefde, and a personal one for Adams, since among the casualties was his younger brother, Thomas, who had accompanied him on the voyage. Following the attack, the ship left Chile and sailed to the island of Santa Maria, where it rendezvoused with the Hoop, only to discover that they had suffered a similar attack on the island of Mocha and had lost even more men than they had.

To further add to their losses, another eight sailors from the Liefde went aboard the pinnace (aka the ship’s boat) and traveled to an island that was inhabited by cannibals. They were never heard from again, but we have a pretty good idea what happened to them. And, of course, there were still the Spanish, who dominated those waters and were out there looking for them.

Things were looking grim for the Dutch expedition, and that’s putting it mildly. There weren’t a lot of friendly places in those waters, so the remaining officers held a council to decide on their next destination. As it happened, one of the men aboard one of the vessels was Dirck Gerritsz, best known as the first Dutchman to visit both China and Japan. The tales he told them convinced them that Japan was probably their best bet, so the two remaining ships set sail for the Land of the Rising Sun.

Japan at a Crossroads

As we already mentioned, the Hoop sank before reaching Japan, and no trace of it has ever been found. Meanwhile, the Liefde only had a handful of men still capable of standing up and steering the ship, and about a dozen or so other crewmen at death’s door. Despite the heavy odds against it, on April 19, 1600, the Liefde made landfall in Bungo Province, on the island of Kyushu.

On the first day, the ship was visited only by curious fishermen who made no attempt to help or hinder the dying men aboard the vessel. On the second day, the local lord, known as a daimyo, sent soldiers to secure the goods, dock the ship, and move the surviving men into a house while he awaited instructions from his superior. In his case, the superior was Tokugawa Ieyasu.

As it happened, Adams arrived in Japan during a crucial moment in the country’s history, the time of the three Great Unifiers: Oda Nobunaga, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, and Tokugawa Ieyasu. Japan had an emperor, but he was there mostly for show as a nominal figurehead. The true power was in the hands of a military ruler called a shogun, and it had been that way for over 400 years by the time Adams arrived on the scene. Since the beginning of the 14th century, the shoguns came from the Ashikaga Clan because they were the strongest faction in Japan.

However, in 1467, a conflict known as the Onin War caused them to lose some of that power. They still had the shogunate, but weren’t strong enough anymore to subdue all the other clans in the country as vassals. From then, the Sengoku or the Warring States Period of Japan began. It lasted for over a century, and it was an almost constant stream of civil wars as all the different clans fought their neighbors for power, but without any of them being strong enough to lay claim to all of Japan.

It was a time of alliances, betrayals, and combat, and it lasted until one man proved strong enough to conquer all the others. He was Oda Nobunaga, but he, too, was betrayed and died before the unification was complete. His former general, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, finished the job, but by the time he was done, he was old and frail. Japan needed a long and stable reign to firmly establish the new government and not descend into chaos again, and that was provided by the third “Great Unifier,” Tokugawa Ieyasu, who founded the Tokugawa Shogunate that went on to rule Japan for over 250 years.

We might have made it sound like Toyotomi and Tokugawa were good ol’ buddies working toward a common goal, but that wasn’t strictly the case. Toyotomi never wanted Tokugawa to seize power. He wanted his own clan to become the new shogunate, led by his son, Hideyori. However, Hideyori was just a little kid, so before his death, Toyotomi created the Council of Five Elders, made up of his most powerful daimyo (including Tokugawa), to rule as regents. On paper, the elders were all loyal to Hideyori, but behind closed doors, intrigues and shenanigans were afoot, as Tokugawa and his supporters intended to dethrone Hideyori. To accomplish this, he needed to deal with the lords who were still loyal to the Toyotomi Clan.

This was the complicated and perilous world that William Adams entered upon coming to Japan. Tensions were running high, and dangers lurked at every corner as he was caught in the middle of a brewing war between two factions. Fortunately for him, Adams could prove to be a valuable asset to the right man.

Meeting the Shogun

Even before Adams got a face-to-face with Tokugawa, he already had a new danger to deal with – the Portuguese Jesuits. The Portuguese had been the first Europeans to make contact with Japan over half a century earlier, and they resented anyone trying to muscle in on their racket. As Catholics, they particularly disliked the Dutch and the English, whom they regarded as Protestant heretics. The Jesuits attempted to convince the local daimyo that the men aboard the Liefde were pirates, not merchants, and thus, deserving of a painful execution. The lord didn’t buy it, though, and refused to take any action without Tokugawa’s approval.

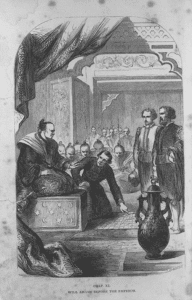

For his part, Tokugawa seemed uninterested in the feuds of Europe. He had his own problems, so he paid little attention to the Portuguese’s efforts to doom the men to death. Instead, he summoned Adams to his court at Osaka Castle.

Their first encounter, done through a Portuguese interpreter, was a fairly standard interrogation: who are you, what do you want, where did you come from, where did you go, where did you come from, Cotton Eye Joe? Maybe not that last part, but we don’t know how accurate the interpreter was, so we can’t say for sure.

Tokugawa was intrigued. In the short term, he was mainly intrigued by the 500 matchlocks, 5,000 pounds of gunpowder, and 5,000 cannonballs that the Liefde had in its cargo hold. That arsenal was quite handy to have should any fighting occur in the near future, and it was just as important to keep it out of the hands of his enemies. So he had the ship moved to his capital of Edo, aka Tokyo, and the sailors were provided with an allowance of money and rice, but were not permitted to leave.

There is sometimes mention that Adams was instrumental in helping Tokugawa become shogun, like his counterpart in the book, and this isn’t true. It’s the biggest difference between the fictional John Blackthorne and the real William Adams. In fact, the most pivotal moment in Tokugawa’s power grab happened just a few months after Adams arrived in Japan. In October 1600, he won the Battle of Sekigahara, where his main rival was killed alongside many of his prominent supporters. From then on, he was the dominant force in Japan, and in 1603, Tokugawa officially received the title of shogun.

While he was still busy consolidating his power, he paid little mind to Adams, who was left to his own devices back in Edo, as long as he didn’t try to leave. But once Tokugawa was in control, he had some free time to spend with his European guests. Fairly quickly, Adams became his favorite as he possessed knowledge that interested the new shogun: mathematics, shipbuilding, astronomy, and the world outside of Japan. In just a few years, William Adams went from tutor to one of the shogun’s most trusted advisors.

Big in Japan

Being in the shogun’s inner circle had its benefits and drawbacks. On one hand, Adams received an estate and a large allowance. On the other hand, making himself indispensable meant that Tokugawa refused to let Adams leave Japan, even when some of his former Dutch crewmates were allowed to go home.

His first big task came in 1604 when the shogun ordered Adams and the other sailors to build him a Western-style ship, the first of its kind constructed in Japan. Adams was by no means a master shipbuilder, but he did have experience from his time in London, and he was successful in building an 80-ton vessel. Tokugawa was sufficiently impressed with his work that he then commissioned the Englishman to construct a bigger, 120-ton ship, which was later used on a trading mission to Mexico.

As a reward for their work, most of the Dutch seamen were sent home in 1605. As we mentioned, Adams wanted to leave, too, but wasn’t allowed. However, Tokugawa had a different prize in mind for him. That same year, he awarded William Adams a large estate on the Miura Peninsula and presented him with the two swords that represented the authority of the samurai. Tokugawa bestowed upon him the title of Hatamoto, a high-ranking samurai who served as a direct retainer to the shogun. To mark this status upgrade, Adams changed his name to Miura Anjin, meaning “the pilot from Miura,” but officially speaking, from that point on, William Adams was dead, and Miura Anjin, the first English samurai, was born. Anjin later married a Japanese woman named Oyuki, and they had two children together: Joseph and Susanna.

We should point out that the first Dutch samurai was born at the same time. Adams wasn’t the only crewmate of the Liefde who entered Tokugawa’s entourage. The second mate, Jan Joosten van Lodensteijn, also became a close advisor and was granted the same title and privileges as Adams, and he became known as Yayosu.

Even though Adams was now a samurai, we don’t want you to think that he rode into battle, or used his shiny new swords to strike down the shogun’s enemies, or anything like that. He had little to no involvement in the internal matters of Japan. What Tokugawa mainly wanted him for was to establish trade relations with Europe. Now that multiple European powers were knocking at Japan’s door, the shogun understood that it didn’t benefit him to grant Portugal a monopoly, so he wanted to reach out to Dutch and English traders.

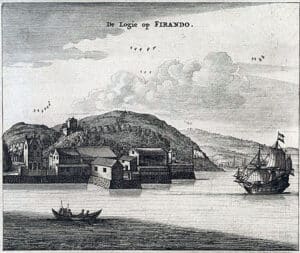

The Dutch East India Company was the first to receive the invitation. The sailors who left in 1605 carried letters from the shogun, but it wasn’t until 1609 that two Dutch vessels finally arrived in Japan – the Griffin and the Red Lion with Arrows. With Tokugawa’s permission, Adams helped the Dutch merchants establish a trading base at Hirado.

Probably just as important as the trading relations Adams helped foster was the one he suppressed with Spain. Initially, Tokugawa allowed the Spanish to trade, send missionaries to Japan, and even to survey Edo Bay as an anchorage for their missions. Adams, however, strongly advised him against this, warning that it was a ploy to set the stage for an invasion. Already, several of his daimyo had converted to Christianity thanks to the missionaries, and Tokugawa feared that, if the trend continued, they might try to overthrow his shogunate. The shogun trusted Adams’s words and took a much harsher stance against Spain and Christians, in general.

Adams was friendly with the Dutch, but he was still an Englishman, so unsurprisingly, he wanted the English to trade with Japan, as well. He didn’t insist on the matter at first because he didn’t think England had a presence in those waters yet. Adams had been away so long that he didn’t know that, in 1600, England founded its own East India Company to conduct trading missions in South and East Asia, and that it already had a settlement in Banten, modern-day Indonesia. He learned of these new developments in 1611 and sent word to Banten, advising them that there was a lot of money to be made on these new shores. And thus, in 1613, the Clove was the first English trade ship to arrive in Japan, captained by John Saris.

As with the Dutch, Adams helped them establish a base in Hirado, but his personal relationship with Saris was a bit contentious. It seems the captain resented the fact that Adams had gone full native – he observed Japanese customs, spoke their language, wore their clothes, and when he was in Hirado, he stayed with a Japanese magistrate instead of with the rest of the Englishmen.

The fact that Adams had fully embraced his new life became evident when the Clove departed Japan. Tokugawa had finally granted him the thing he had desired for years – the permission to return home to England. But this time, it was Adams who said “no.” He didn’t want to go back anymore. Fifteen years had passed since he left Europe aboard the Liefde. This was his home now. Instead, he accepted a lucrative position with the East India Company’s new trading factory in Hirado, earning a yearly salary of 100 pounds.

Tokugawa Ieyasu died in 1616 and was succeeded by his son, Tokugawa Hidetada. Technically, Hidetada had been shogun since 1605, but realistically speaking, his father still called the shots while he was alive. While not hostile toward Adams, Hidetada did not value his counsel for two reasons: one, he had his own trusted advisors; and two, Hidetada wanted to reverse his father’s policy of free trade, intent on minimizing foreign influence as much as possible, as he considered it a threat to the shogunate.

Even so, Adams was not deprived of the privileges he had previously enjoyed. He spent his last few years quietly and died just four years later, on May 16, 1620, aged 55. Adams did leave Japan a few times, but he stayed in Asian waters, conducting trading missions to Thailand and Vietnam. He never returned to England.