Today’s protagonist once wrote a poignant thought about the ‘Art of Biography’, wondering ‘[…] whether the lives of great men only should be recorded. Is not anyone who has lived a life, and left a record of that life, worthy of biography – the failures as well as the successes, the humble as well as the illustrious[?]’

Ironically, today we will make our best effort to capture at least some of the successes of her illustrious life.

On paper, she had a head start in life, being born in a family of wealthy intellectuals. But her existence was marred from the start by mental illness and sexual abuse.

Undeterred, the strength of her intellect ploughed on, and she became one of the leading innovators of modernist literature.

This is the life of Virginia Woolf.

A Crowded House

The baby who would become author Virginia Woolf was born Adeline Virginia Stephen on the 25th of January 1882, in Hyde Park Gate, London.

Her family background was rather illustrious.

Her grandfather, Sir James Stephen, had authored the bill to abolish slavery in 1833.

Her father, Leslie, was an author and editor, founder of the Dictionary of National Biography.

In 1867, Leslie had married ‘Minny’ Thackeray, daughter of novelist William Makepeace Thackeray. The two had a daughter, Laura, in 1870, but five years later Minny died of eclampsia.

After three years of grieving, Leslie remarried with Julia Duckworth, a model for pre-Raphaelite painters. Julia was also a widower, and brought her own three children into the new household, Stella, Gerald and George.

Leslie and Julia made it a point to overcrowd even more their home by having four further children together:

Vanessa, born in 1879, later to become a painter.

Thoby, in 1880, was a promising intellectual, but died aged just 26.

Virginia.

And Adrian, in 1883, who would become a psychoanalyst. The four Stephen siblings were very close, and highly gifted from an early age. Virginia displayed a talent for writing stories since the age of five, penning long serials about evil spirits lurking in rubbish heaps.

As much as Virginia loved her crowded house in London, her favorite place was Talland House, the family’s summer getaway in St Ives, Cornwall.

From its windows, she admired the views of Godrevy lighthouse, towering above the sea. Or enjoyed the sounds of children playing in the terraced gardens. In the evenings, she would withdraw from the dining rooms, to compose short stories in the style of Nathaniel Hawthorne.

All those memories of St Ives stayed with Virginia well into adulthood. To the point that she later wrote how her entire life was ‘built on that, permeated by that: how much so I could never explain.’ Virginia’s love for writing and reading drew her very close to his father. The two would spend hours together, sharing books or making up stories.

Virginia and Leslie took long walks together, during which he taught her to dig into the more prosaic aspects of everyday life, and extract ‘fountains of poetic interest.’

Nonetheless, Leslie had an ambivalent attitude towards the role of women as intellectuals. While he encouraged his daughters to read, write and learn, he did not believe women could lead productive literary or artistic careers.

As Virginia grew older, she resented this patriarchal attitude, but she had other, more problematic, male figures in her life: Gerald Duckworth, one of her much older half-brothers had once touched her inappropriately, while on holidays at St Ives.

He was 18 at the time, Virginia only six. The incident left her prone to sexual fear and instilled in her a resistance to aggressive masculine authority. This event surely clouded the idyll of her childhood, but the worse was to come when Virginia entered her teens.

In May 1895, her mother Julia died of heart failure.

Julia’s daughter, Stella Duckworth, took on the mantle of surrogate mother. But two years later, she, too, died, due to the complications of pregnancy.

With Julia and Stella gone, there was no one left to keep under tabs Virginia’s other half-brother George.

According to Virginia’s own memoirs, George would ‘visit’ her at night, forcing himself on her and calling her ‘beloved’. But by day, he would ridicule her looks and called her ‘the poor goat’.

It was too much for a 15-year-old girl to take. In September of 1897, Virginia first recorded in her journal a wish to die.

‘This diary is lengthening indeed but death would be shorter and less painful.’

Seasons in the Abyss

Virginia soldiered on. But life kept treating her like a punch bag, delivering jabs and hooks of misery.

First, Leslie died in March 1904.

Understandably, the 22-year-old Virginia suffered a mental collapse, which led her to attempting suicide by jumping out of a window. She recovered thanks to Violet Dickinson, a friend of the late Stella. Violet was older, wise, and kind: just the type of motherly figure the young Virginia needed.

Violet nursed her back to health, physically and mentally. Along the way, the two developed a friendship which eventually became romantic.

During the same eventful year, Virginia and her sister Vanessa moved to Gordon Square, in the Bloomsbury area of London. This was the epicenter of bohemian life in London, an area rife with non-conformist intellectuals many of whom gravitated around the Stephen siblings.

Their friends included activist and author Leonard Woolf, biographer Lytton Strachey, artist Roger Fry, economist John Maynard Keynes and art critic Clive Bell, who would later marry Vanessa.

By moving into that milieu, Virginia and Vanessa were rejecting the habits and values expected from two young ladies in Edwardian England. They replaced polite small talk with discussions about politics and literature, or shopping trips with visits to art galleries.

And during the summer of 1905, Virginia ditched London’s high society events for long walks across Cornwall’s countryside.

During that period, she kept a diary, which became the origin of her later narrative experiments.

In her journal, Virginia described how she abandoned the well-trodden roads to venture into barely visible paths, ignoring the artificial barriers imposed by man on nature. These ramblings were an early metaphor for her later works, in which the narrative ignored the artificial signposts imposed by traditional plot lines: a character’s birth; a marriage; someone’s death.

Virginia would instead explore apparently insignificant moments in time, which nonetheless can shape someone’s life.

Virginia’s own life, however, was to be shaped by the tritest of plot points: the death of another character.

In 1906, older brother Thoby succumbed to typhoid while traveling in Greece.

This event appeared to ignite a steady decline in Virginia’s mental health, although initially she did her best to remain mentally active and productive. While working as a teacher in a night school for workers in south London, she composed her first short story, ‘Phyllis and Rosamond’.

The plot was inspired by Virginia and Vanessa’s own experiences in London’s upper-middle class milieu. Or better, it explored the question: what would have happened to two intelligent and ambitious sisters should they have not escaped from that environment?

The answer was: they would have been trapped in a lifeless limbo, like hazy figures in the background of a party. Two non-entities, little more than decorative props, waiting for someone to marry them.

And yet, Virginia felt that even this state of non-existence, so common, so typical of the era, was worth recording. Unlike her protagonists, Virginia pretty much stood out from the background, getting involved in the big political issues of the time, such as the campaign for women’s rights and suffrage.

But eventually, her mind deteriorated, and in July of 1910, Virginia was committed to Burley, a sanatorium in Twickenham.

She absolutely loathed the experience, writing to Vanessa that she saw jumping out of a window as her only way out. This extreme means of escape was not necessary, however, and Virginia was dismissed after less than two months.

Upon her release, Virginia moved into a new house in Brunswick Square, Bloomsbury, sharing lodgings with her brother Adrian, and other friends. Leonard Woolf was one of them, and he was interested in becoming more than just a friend. The two got engaged and eventually married on August 10, 1912.

Leonard was a positive presence in Virginia’s wife: he helped her cope with her bouts of mental illness, and coached her into writing her first novel, ‘The Voyage Out.’

But the relationship was not entirely a bed of roses. Leonard could not or would not consider Virginia’s sexual fears and history of abuse. He even considered her to be “a sexual failure”.

From her side, Virginia had no qualms in offending Leonard’s background, introducing him as “a penniless Jew.”

The adjustment to married life, and tensions that came with it, may have pushed Woolf into a period of depression in 1913. Her doctor sent her back to Burley for another summer in the abyss. When Virginia walked out, she was suicidal.

On September 9, she consulted with two distinguished psychiatrists: Dr Maurice Wright and the aptly named Sir Henry Head.

All they could advise was a third admission to Burley, something that Virginia could not swallow.

What she did swallow instead was a massive dose of barbiturates. She barely survived, thanks to Leonard and Dr Head, who arrived at the right time and pumped her stomach.

Whilst recovering, she threw herself into finalizing ‘The Voyage Out’, published in March of 1915.

The novel lays out some of the main themes that Woolf would explore in later works, such as the stifling condition of married women in early 20th Century Britain.

‘The Voyage Out’ was well received by critics, but it was not a bestseller. Moreover, the stress associated with its publication led Virginia to suffer another mental breakdown, a violent episode of incoherent screaming, followed by a comatose state.

This was followed by another admission at Burley.

The medical staff tried to persuade Leonard and her family that Virginia’s sanity had gone, worn out by neurasthenia, or nervous exhaustion. Contemporary psychiatrists tend to agree that she was beset by bipolar disorder, instead, driven by both nature and nurture.

Mental illness ran in her family.

Grandad James suffered from cyclothymia, which causes intense mood swings. He had been institutionalized after running naked through Cambridge and died in an asylum.

Her dad Leslie was also cyclothymic, while her mum Julia suffered from depression.

Her siblings and half-siblings were not immune either: Laura, Leslie’s daughter from his first marriage, suffered from an undefined psychosis. Vanessa and Adrian had cyclothymia, too and the unfortunate Thoby experienced hypo-manic episodes.

Virginia’s already fragile mental state was further compromised by the traumatic experiences suffered since childhood: the series of deaths in the family and the vile sexual abuse perpetrated by the Duckworth boys.

And yet, it would be reductive to identify Virginia Woolf with a mental health condition. Her vitality, resilience and sheer will power would not allow her to succumb to institutionalization.

She would not accept to lead a life defined by malaise, a life adrift driven by the storms of mania or the dead calm of depression.

Against all medical opinion, by November, 1915, Virginia had recovered and was ready to leave Burley.

After twenty years of half-light, she was ready to throw open the curtains and take on the most productive period of her life.

Pressing On!

After Virginia’s recovery, Leonard was still worried that the effort of writing would cause her to have another breakdown and looked for a distraction for her. As Virginia had an interest in printing and binding books by hand, he ordered a hand-printing machine.

This activity started as a hobby, but soon it became a business: Hogarth Press.

The Woolfs initially used Hogarth Press to publish their own works. This was a relief for Virginia, who dreaded submitting her manuscripts to the prying eyes of editors and publishers.

Soon they expanded their catalogue to include small and experimental works, likely to be rejected by commercial publishers. These included writings by their friends E.M. Forster, and John Maynard Keynes, but also by Sigmund Freud and T.S. Eliot.

In 1919, Virginia released her short story ‘Kew Gardens’ via Hogarth Press. The story contrasts the aimless meandering of eight characters against the purposeful march of a snail, and attracted the attention of the Times Literary Supplement.

The favorable review led to hundreds of orders and commercial success. So much so, that Leonard and Virginia had to forgo the hand printing press and hire a commercial printer. While Hogarth Press was taking off, Virginia was completing her second novel ‘Night and Day,’ published in October of 1919.

Woolf explores again the theme of women who struggle to achieve their full potential, locked in a society who accepts them only as wives and daughters.

The main character Katherine actively opposes her milieu of middle-upper class intellectuals: first, by embracing mathematics instead of poetry; and then by rejecting the courtship of a poet, as she pursues the love of an upstart solicitor.

‘Night and Day’ was the first in a series of writings in which Woolf shaped the defining characteristics of the modern novel.

She introduced the principle that writers did not need sensational events to propel a story or develop a character. An ordinary mind, on an ordinary day, was worthy of being narrated in a novel. She aimed to capture the ‘moments of being’ of these ordinary minds: climactic inward events or epiphanies that may strike her characters whilst they conduct the most mundane activities.

Woolf adopted these principles in her follow up novels, ‘Jacob’s Room’ of 1922 and ‘Mrs Dalloway’, published in 1925.

The latter novel takes place over a single day in June, a concept inspired by James Joyce’s ‘Ulysses.’

Mrs Clarissa Dalloway roams London, looking to buy flowers for a party she is throwing. She is renowned amongst London’s High Society as a bright and lively hostess, although she is not entirely satisfied with her own life.

Clarissa’s urban travels are mirrored by her internal meanderings, as she questions the meaning of her own existence and reminisces about her first love, Peter, and about her lone homosexual experience.

Woolf then introduces the second main character, Septimus Warren Smith. A WWI veteran afflicted by shell shock, Smith is plagued by hallucinations, by an inability to feel emotions and worst of all, by poor medical treatment.

The two never meet. But during the party, Clarissa overhears a guest telling how Septimus committed suicide earlier that day, by jumping out of a window. Despite this tragic revelation, the novel ends on an optimistic note. By reflecting on Septimus’ suicide, Clarissa finds a new interest in the beauty of life, and reconnects with former lover Peter.

Many contemporary critics and readers consider Mrs Dalloway as Woolf’s best novel, but it’s a close tie with her follow-up title, ‘To the Lighthouse’, published in May 1927.

The book is divided into three sections: ‘The Window’, ‘Time Passes’, and ‘The Lighthouse’.

The first section, ‘The Window’, takes place over a single day. The Ramsays are at their holiday home on the Isle of Skye, a stand in for the Stephens’ own retreat in Cornwall.

One of the children, James, is planning a boat trip to a lighthouse, but his father talks him out of it, claiming bad weather. The second, and shorter section, ‘Time Passes’, covers ten years of events, including WWI. During this period, the Ramsay house, a symbol for civilization, rots away, abandoned.

“The house was left; the house was deserted. It was left like a shell on a sandhill to fill with dry salt grains now that life had left it.”

In this section Woolf hastily introduces the death of important characters, as quick edits in between square brackets. My favorite example is “[A shell exploded. Twenty or thirty young men were blown up in France, among them Andrew Ramsay, whose death, mercifully, was instantaneous.]”

In the final section, ‘The Lighthouse’, James finally completes his trip to the lighthouse, ten years after originally planned.

As with many of Woolf’s novels, it is difficult to pinpoint a single key theme. The more evident ones are the nature of time, and how patterns of delay, repetition, and inaction can affect one’s life.

Despite its complexity, the novel was well received by critics and readers, much to the surprise of the author! On June 6, 1927 she noted in her diary: ‘They don’t laugh at me any longer … Possibly I shall be a celebrated writer.’

Virginia’s Room

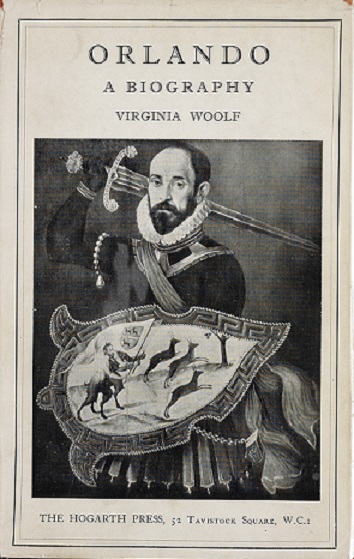

This celebrated writer defied all expectations with her next work, ‘Orlando: A Biography,’ of 1928. Almost fantasy in tone, this novel features the titular character who switches gender at a whim, and lives through centuries of British history.

The novel defies the traditional, linear concept of time: as the protagonist accumulates memories, each one of them becomes a wormhole, transporting her, or him, back to a different period. But Orlando can also be read as a fictional biography of a real-life character: poet, novelist, and horticulturist Vita Sackville-West.

Vita and Virginia had first met in 1923, struck a friendship and took holidays together in France and Italy.

Virginia idolized Vita, and their friendship developed into a short romance, which became physical only on two occasions.

The unstoppable Woolf hit the bookshelves again the following year, with the essay ‘A Room of One’s Own’, one of her most celebrated feminist writings.

In this work Virginia addresses the pressures which deny the intellectual and professional development of women: the confinement to the domestic sphere; conformity to the patriarchy; but most of all, the inability for women to have their own income and privacy.

Hence the title: ‘A woman must have money and a room of her own if she is to write’.

The essay also looks at how history is written: as a succession of wars waged by powerful Kings and Generals. Woolf invites readers to consider a counter-historiography instead, one focused on those women excluded from historical records.

Generations of mothers and daughters who maintained domestic order and social peace– which were regularly destroyed by militaristic thugs.

The next effort was 1931’s ‘The Waves,’ Virginia’s most experimental work. The narrative is structured as six soliloquies, voiced by three men and three women over a single day – again! – as they cope with the death of a dear friend.

The characters do not show any external expression of grief, but the author reveals their personalities through their internal stream of consciousness.

In 1932, the writer launched into another ambitious project, which occupied her for the next five years. This was ‘The Years,’ a family chronicle which became Woolf’s best-selling work during her lifetime.

Here, Woolf follows the extended Pargiter family, heavily influenced by her own. Each section starts with a sweeping narration, describing the sky over Britain, or London in particular, before ‘zooming’ into the consciousness of a particular character.

Their seemingly random activities, dialogues, and thoughts, take the reader through fifty years of British history and institutions, analyzing how they have shaped the consciousness of individuals.

The initial draft included a running social commentary on the condition of women, which Virginia edited out, and then published in 1938 as ‘Three Guineas.’

This second feminist essay identifies the dominant issues for women of the 20th Century: lack of access to education and professional advancement. If women were so excluded from the public sphere, how could they prevent the world from slipping into another war?

According to Woolf, exclusion of women led to an unbridled patriarchal society. Which in turn had a direct link to the rise of fascism in Europe, and thus to the risk of international conflict.

That conflict, WWII, of course broke out eventually, in September of 1939.

Virginia had started working on what would be her final novel, ‘Between the Acts,’ which she continued writing under the Blitz. In September of 1940, the Woolf’s home in Bloomsbury was bombed by the Luftwaffe, and Virginia and Leonard moved to their country home, Monk’s House, in Rodmell, Sussex.

Rodmell lies little less than 5 km from Newhaven.

Unbeknownst to them, this was the intended landing port for Operation Sea Lion, the planned Nazi invasion of Britain. And little did they know that Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS, had included their names in a list of intellectuals to be immediately arrested!

While he had no knowledge of these plans, Leonard feared a German landing and was aware of the dangers for a Jew and his wife. He devised contingency plans for him and Virginia to commit suicide together. An idea which the writer did not like one bit, as she was still busy with her novel!

But the hard work on ‘Between the Acts’ and the tension created by the war were taking a heavy toll on her. Virginia could feel that her mind was beginning to falter: she feared that her mental illness would resurface violently.

On the 27th of March, Virginia wrote to her publisher confiding that she was not satisfied with her current draft, and she aimed to revise it later in the year.

Did she really plan to continue working on her latest novel?

We only know that the following day she did pick up pen and paper, but to leave a note for Leonard:

“Dearest, I feel certain I am going mad again. I feel we can’t go through another of those terrible times. And I shan’t recover this time.”

Around 11:45am, Virginia Woolf filled her pockets with stones, walked into the fast current of the River Ouse and let herself drown. Her body was recovered only on the 18th of April. Leonard buried her ashes in their garden, under one of the two elms with interlaced branches.

They had called them Leonard and Virginia.

SOURCES

LIFE

https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-37018?rskey=8PSlYD&result=3#odnb-9780198614128-e-37018-div1-d1694252e179

https://mantex.co.uk/virginia-woolf-life-and-works/

https://www.bl.uk/people/virginia-woolf

Boeira MV, Berni GÁ, Passos IC, Kauer-Sant’Anna M, Kapczinski F. Virginia Woolf, neuroprogression, and bipolar disorder. Braz J Psychiatry. 2017;39(1):69-71. doi:10.1590/1516-4446-2016-1962

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7112729/

Hogarth Press

https://www.bl.uk/20th-century-literature/articles/the-hogarth-press

Vita Sackville-West

https://mantex.co.uk/vita-sackville-west-biography/

WORKS

Phyllis and Rosamond

https://mantex.co.uk/phyllis-and-rosamond/

The Voyage Out

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/148905.The_Voyage_Out

https://www.gutenberg.org/files/144/144-h/144-h.htm

Night and Day

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/116056.Night_and_Day

Mrs Dalloway

https://interestingliterature.com/2015/05/interesting-facts-about-mrs-dalloway/

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/14942.Mrs_Dalloway?ac=1&from_search=true&qid=hWj9GLYyuZ&rank=1

To the Lighthouse

https://interestingliterature.com/2016/02/a-summary-and-analysis-of-woolfs-to-the-lighthouse/

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/59716.To_the_Lighthouse

https://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks01/0100101.txt

Orlando

https://interestingliterature.com/2015/06/the-best-virginia-woolf-books/

https://lithub.com/on-orlando-and-virginia-woolfs-defiance-of-time/

The Waves

https://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks02/0201091h.html

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/46114.The_Waves

The Years

https://www.goodreads.com/book/show/18852.The_Years?ac=1&from_search=true&qid=3kU5drVf8D&rank=1

https://campuspress.yale.edu/modernismlab/the-years/

Three Guineas

https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/three-guineas-by-virginia-woolf