They say that you should set a thief to catch a thief as no one else understands the criminal mind better. Perhaps the most shining example of this idiom is Vidocq, the man who is now hailed as the father of modern criminology.

He went from a life of crime spent either on the run or in the prisons of France to establishing a national detective police force that served as the model for Scotland Yard and others that followed it. He employed proto-forensic techniques such as ballistics and casting foot impressions. When he left the force, he started his own agency and became the world’s first private eye.

Vidocq goes against many of the tropes we have of the stereotypical detective. He was far from brilliant and his success was more down to him being methodical and persuasive. He had a violent streak and was chiefly motivated by money. He made plenty of enemies in his career and, as you are about to see, his life was filled with almost as many failures as successes.

Early Days

Most of the information surrounding the detective’s early years comes straight from the horse’s mouth courtesy of the Memoirs of Vidocq, the autobiography he published with the help of a ghost-writer around 1828. Feel free to take it with a generous helping of salt.

Eugène François Vidocq was born in the city of Arras, in the Pas-de-Calais department in northern France, on July 23, 1775. He was the third of seven children of Nicolas Joseph François Vidocq, a prosperous baker, and his wife, Henriette Françoise. He was born in the house next to the one where Maximilien Robespierre was born sixteen years prior.

Image suggestion: The Citadel in the Place d’Armes

The Vidocq family lived in a rough area of Arras called the Place d’Armes and, consequently, the young Eugène got into scraps at an early age. Fortunately for him, Vidocq had a large, strong constitution and, by age eight, already bragged about being the terror of the children in the neighborhood. He also took up fencing when he was young and, by age thirteen, was prodigious with the foil.

First Troubles with the Law

Vidocq’s life of crime started as a teenager and his first target was his own family business. The youth worked for his father’s bakery by making deliveries around town and would dip into the till for money to spend at the pub. It was also at this time that he began making the acquaintances of the city’s local blackguards, cons, and other various villains. When his father discovered this, he began locking the till, but the enterprising Vidocq forged the key with the help of a blacksmith’s son.

When the senior Vidocq, again, put an end to his son’s scheme, the offspring began simply stealing items and pawning them. This led to his first arrest and a few days in Baudets, the local jail.

Instead of setting him straight, this experience convinced Vidocq to go for one big score and then leave town. He broke into the bakery with the help of a friend and absconded with 2,000 francs. He split the money in half with his accomplice and each went their separate ways.

Life on the Streets

Early on in his life on the run, Vidocq learned a harsh, but necessary lesson: there is always a bigger fish. He might have considered himself a successful criminal, but was still naïve in the ways of the world. While traveling through Belgium to secure passage on a ship, he met an amiable stranger who took him to a house full of friendly, beautiful women. There, he was drugged and he woke up the next morning on the docks, half-naked, with only a few crowns to his name.

Vidocq was forced to take employment where he could find it so he joined a troupe of performers. He was treated miserably, beaten regularly and given scraps for food. His appearance became so wretched that, at one point, he was asked to pretend to be a savage island cannibal who feasted on raw flesh. This prompted him to leave and he joined a group of puppeteers, but this new gig did not last long as he was kicked out for making sweet eyes at his employer’s wife. From there, he hooked up with a traveling group of peddlers led by one Father Godard.

Back Home

When opportunity arose, Vidocq returned home to Arras where his father, eventually, forgave him. He enlisted in the army and joined the Bourbon regiment where his reputation and his temper would often lead to fights. After six months, Vidocq had earned the nickname “Reckless” after engaging in fifteen duels and killing two men.

In 1792, France entered combat with Austria in the War of the First Coalition. Vidocq took part in several battles and was promoted to grenadier, but deserted after receiving a court-martial for hitting an officer. He joined the 11th Chasseurs under a different name and, although his desertion was discovered, a captain interceded on his behalf and all was forgiven. After being shot in the leg, the 18-year-old Vidocq returned to Arras.

From One Prison to the Next

Vidocq’s years as a young adult seemed to have been mostly divided between the prison cell and the army. On the rare occasions that he was free of both, he typically engaged in romantic trysts or felonious ventures. He even married once, but the relationship ended quickly.

His adventures took him to Brussels where he presented himself as Monsieur Rousseau since Eugène Vidocq was, once again, wanted for desertion. In 1795, he joined the flying army and became a hussar captain. He caught the eye of an elderly, widowed baroness who bequeathed him a generous sum that enabled Vidocq to live it up in Paris for a while.

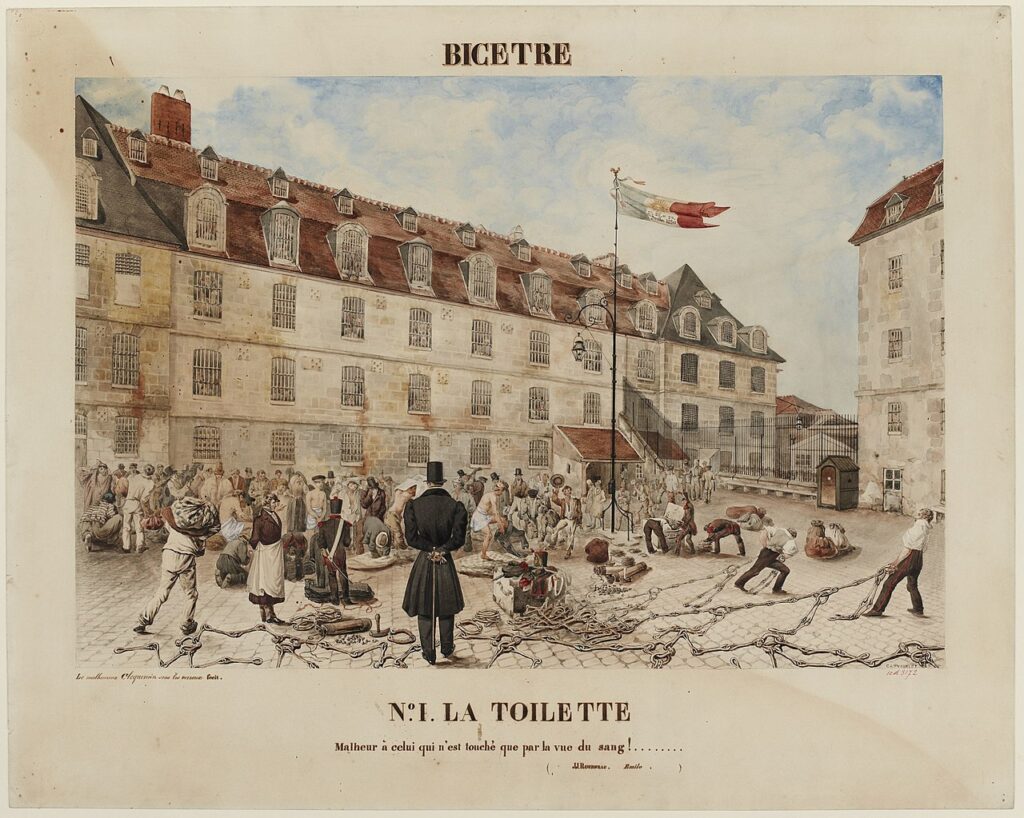

After a few months, the money was gone and Vidocq was back in prison. Here, he discovered a new talent – forgery – and, with the aid of a lover named Francine Longuet, escaped several times, but was always recaptured soon after. In just five years, Vidocq had been imprisoned in Bicêtre, Douai, Senlis, Brest, and Toulon, not to mention once being shanghaied in Rotterdam and having a short stint as a privateer aboard a Dutch ship.

The Turnaround

In 1800, a 25-year-old Vidocq escaped prison and made his way back home. He found out that his father had died the previous year. He wanted to stay with his mother, but was recognized and had to flee again. In Rouen, he assumed the identity of a merchant named Blondel. He was successful for a couple of years and planned to send for his mother before being discovered and having to go on the run once more. Time and time again, Vidocq tried to start a new life in a new city, but it seemed that everywhere he went, his past soon caught up with him.

In 1809, Vidocq found himself in familiar surroundings after being arrested and sent to the prison in Bicêtre. Undoubtedly, he could have escaped. He could have used a disguise, or bribed the guards, or climbed the walls and, eventually, Vidocq would have been a free man again. However, he had grown weary of prison escapes and the fleeting liberties they provided. He offered to put his experience and reputation to good use and become a prison informant. A police chief named Jean Henry accepted the deal and relocated Vidocq to La Force Prison in Paris.

It didn’t take long for the prisoner to prove his worth. Vidocq made the acquaintance of France Tormel, a criminal who was part of a gang of prolific robbers. Although already imprisoned, it would not be long before Tormel was released due to lack of evidence or witnesses. Vidocq managed to gain his confidence enough that the felon revealed to him the residence of his mistress. Sure enough, police conducted a raid and found enough stolen merchandise to sentence Tormel to eight years. Not only that, but the criminal still trusted Vidocq and gave him enough information to get his accomplices arrested, as well.

For twenty-one months, Vidocq plied his informant services between the walls of the prison. Eventually, Henry realized that he would be more useful on the outside as he would be able to infiltrate many criminal establishments instead of just waiting for the criminals to come to him. They secured his release and made it look like just another escape.

Vidocq Is Out

For the first time in a long while, Eugène Vidocq could walk the streets as himself without having to worry that the first officer who recognized him would try to arrest him.

He wasn’t completely a free man, though. Vidocq was a secret agent in the service of the state. His goal was to gather information that resulted in the prevention of crime and capture of felons. His first collar was a counterfeiter named Watrin. In his autobiography, Vidocq pointed out that this was the beginning of a problem that dogged him his entire time on the force and well into his career as a private detective. All the other officers were jealous of his success and relished the opportunity to see him fail.

Under the old adage of “two heads are better than one”, Vidocq brought in some help and organized an informal unit called the Brigade de la Sûreté (Security Brigade) to aid in his crime-fighting. It consisted mostly of other reformed criminals such as himself.

Back then, France’s police force was mainly divided in two. There was the police politique which was the secret police that handled covert operations and uncovered intrigues against the state. And there was the standard, man-in-the-street uniformed police that dealt with common crimes like theft, murder, and fraud.

Crucially, Vidocq convinced his superiors that his agents should avoid the uniform and, instead, don plain clothes and even disguises to help them infiltrate areas that were, otherwise, off-limits to police.

The Sûreté Is Born

The group was a success. Less than a year after it appeared, the Sûreté officially became a unit of plainclothes detectives under the purview of the Prefecture of Police of Paris with Vidocq as its first chief.

Fortunately for him, the man at the top, Napoleon, was also a keen reorganizer of France’s police force. He established the Prefecture of Police in 1800 and also increased the numbers and responsibilities of the gendarmerie who, up until that point, functioned mainly as a semi-militarized force dispatched to keep the peace in rural areas of the country. Seemingly, Bonaparte approved of Vidocq’s revolutionary approach to crime-fighting and, a year later, further expanded the Sûreté into the state security service known as the Sûreté Nationale.

Vidocq trained all of his agents personally. Even when he had a few dozen men under him, he still enjoyed dressing up like a beggar and hitting the streets for some undercover work. His unit was responsible for hundreds of arrests and reportedly decreased the crime rate in Paris by up to 40 percent. According to criminologist John Philip Stead, in 1817 alone the Sûreté made 811 arrests, including 341 thieves, 46 forgers, 14 escaped prisoners, and 15 assassins.

1817 turned out to be a particularly fruitful year for Vidocq because he also received a full pardon for his past crimes from King Louis XVIII. Up until that point, although he was a superior officer with the Paris police force, Vidocq was still, technically, a wanted criminal.

The First Retirement

The following decade proved to be a more turbulent time for the policeman, both personally and professionally. He married again in 1820, but his wife passed away four years later and his mother died shortly after.

In his professional life, Vidocq started to lose the support of his superiors. Jean Henry retired and the next police chief, Marc Duplessis, was not a fan of the Sûreté. Jules Anglès, the police prefect who obtained a pardon for Vidocq, also had to retire after failing to prevent the assassination of Charles Ferdinand, Duke of Berry. Finally, the king himself died and was succeeded by Charles X.

Vidocq always maintained that the antipathy showed to him by other members of the police force was due to envy of his success. While there was certainly plenty of that, there was also resentment that a criminal would advance so high up the ranks without facing any serious consequences for his illicit past.

At the same time, Vidocq became quite wealthy and famous during his career in law enforcement. He rubbed elbows with Parisian elite like Victor Hugo and Honoré de Balzac and made enough money to start his own paper company. There were unsubstantiated rumors that he continued his criminal activities, but now he just did it with the help of the law.

By 1827, Vidocq had had one too many confrontations with his new boss. After 18 years on the force, the 52-year-old tended his resignation to Marc Duplessis. The police chief was happy to be rid of him although, bizarrely, he appointed as his successor another ex-convict agent named Barthelemy “Coco” Lacour.

A Short Return and a Second Retirement

Vidocq might have been a shrewd criminal and a pioneering detective, but he was not a very good businessman. It did not take long before his company went bankrupt but, on the bright side, the time off allowed him to put down his memoirs.

By 1831, Duplessis was gone and the new police prefect, Henri Gisquet, invited Vidocq back on the force. He was chief of the Sûreté again, but his position was short-lived. Perhaps it was merely a symptom of the instability felt in France during the July Monarchy, or maybe due to the cholera outbreak that was ravaging the country, but people showed little indulgence towards Vidocq and his group of ex-convicts. A few instances occurred in short succession where agents of the Sûreté were accused of acting as provocateurs against rioters and some were even implicated in a theft.

The unit’s actions became harder and harder to justify and, by the end of 1832, Vidocq was once again “cordially invited” to resign. He did so by citing concern for the health of his third wife who, by the way, was also his cousin. Following his departure, the Sûreté was purged of anyone who had a criminal record, even for minor offences.

From Spy to Private Eye

The former agents did not have to look long for a new job. In 1833, Vidocq founded Le Bureau des Renseignements pour le Commerce (“Office of Information for Businesses”). For a fee, clients could access Vidocq’s database of profiles on crooks and frauds. Should the need arise, they could also hire agents to conduct personal investigations and surveillance into their interests which often had nothing to do with business and, instead, pertained to private matters such as adultery or finances.

Business information bureaus already existed, but because of the extra investigation services, many consider Vidocq’s new endeavor to constitute the world’s first private detective agency. Once again, he predominantly hired ex-convicts, many of them former agents of the Sûreté since he already trained them.

If the rest of the police force had contempt for Vidocq before, now they loathed him. Many were not pleased with the idea of an extrajudicial group investigating crimes for the highest bidder. Accusations were thrown now more than ever before that Vidocq and his detectives operated in a grey area of the law, at best, and did not shy away from a few illegalities to finish the job.

You can’t argue with results, though, and the agency flourished at first. However, his quarrels with the true police force led to several arrests and seizures. The new police prefect, Gabriel Delessert, was definitely not a fan of Vidocq and always looked for a new chance to crush his business. That opportunity arrived in 1842 when the prefect ordered a massive raid on the agency which resulted in Vidocq’s arrest. He stood accused of fraud and illegal arrest.

Eventually, Vidocq was free again, but not before spending 11 months in the prison of the Conciergerie. When he was released, he was 67 years old and it became pretty clear to him that his best days were far behind him. He spent the rest of his life mostly out of the limelight and died in 1857.

Elementary, My Dear Vidocq

Vidocq laid the groundwork for the calling of the detective, but we should be clear that he was never a Sherlock Holmes-type character. He did not fit our image of the typical brilliant detective who gives brainy summations in a room full of suspects and reveals how the murderer did it while chewing on a lit pipe. If anything, he was a more successful psychologist than detective. He knew how to use his appearance, his reputation, and his attitude to get other criminals to trust and confide in him.

Another dull, but practical ace up his sleeve was his obsession with keeping accurate and detailed records on all the criminals he encountered. Vidocq often boasted of having an incredible memory, but he knew that his agents were not as gifted. Early in its infancy, the Sûreté began making index cards for the rogues of Paris, listing their physical appearance, distinguishing traits, prior convictions, modus operandi, and any other information that might prove useful. The system was primitive, but it worked, and it came in real handy later when Vidocq started his private agency. The Sûreté made use of it for decades until it was overhauled and improved by Alphonse Bertillon.

This being said, let’s not completely detract from the man’s accomplishments as Vidocq put his talents to good use in ways very few other crime-fighters had done up until that point. He’s had, at least, a handful of cases that would serve well for a Sunday afternoon crime show.

On one occasion, Vidocq met early one morning with a suspected thief named Hotot. The latter looked tired, his clothes were wet and his boots were muddy. Clearly, this was a man who had had a busy night. Vidocq excused himself and went to inquire about burglaries that happened the night before. He arrived at a crime scene and noticed a pair of footprints which made him think of Hotot’s muddy boots. He had an agent fetch some plaster of Paris and he made a cast of the prints which he then matched to the criminal’s boots. Hotot confessed and was sent to the galley.

Image suggestion: Cap and ball pistol

Another time, Vidocq investigated the notorious murder of Countess Isabelle d’Arcy. Everybody assumed her husband had shot her, but the detective relied on a primitive form of ballistics to prove the count innocent. He had the doctor extract the bullet from the countess’s body – something he had to do in secret because it was highly irregular for that time – and showed that the ball was too large to fit in Count d’Arcy’s dueling pistol. Instead, Vidocq matched it to the weapon of the countess’s lover who confessed.

Lunch with a Side of Murder

Eugène Vidocq might be long gone, but his legacy lives on. His literary friends immortalized him in their books as Balzac based several characters on him, chief among them the criminal mastermind Vautrin. In his seminal work, Les Misérables, Victor Hugo drew inspiration for both of his main characters, the convict Jean Valjean and the policeman Javert, from the dual life of Vidocq. The detective himself left behind quite a complimentary account of his exploits in the form of his memoirs. But perhaps no other tribute is more fitting than the Vidocq Society.

Back in September 1990, three criminal experts met for lunch. William Fleisher was a retired Philadelphia police officer and FBI agent, Frank Bender was a forensic sculptor, and Richard Walter was a criminal psychologist. They started talking shop and the discussion, eventually, turned to cold cases.

The three men realized that their knowledge and experience could prove to be an asset to a detective who is stuck looking for that one little clue that could lead to a break in the case. Not only that, but they knew plenty of other people who could also lend their expertise. Thus, the Vidocq Society was born.

How It Works

The organization meets once a month at the Union League of Philadelphia. It has 82 permanent members (one for each year that Vidocq lived), although many others have joined as Special members by invitation only. They include forensic scientists, law enforcement officers, prosecutors, profilers, medical examiners, and psychologists. Seldom will you find more experts on crime gathered under the same roof.

The members have lunch and listen to an investigator who is there to present a murder case. He is stumped. He is out of leads and the trail has gone cold for years. He is hoping that the people there might have some extra insight.

Members of the Vidocq Society offer guidance and advice and, in certain cases, even travel to the officer’s jurisdiction to take a more hands-on approach with the investigation. Over the years, the society has concentrated its efforts on cold cases from small or underfunded police precincts where its efforts would have the largest impact.

The Legacy Continued

The society first tasted success in March of 1991. The family of a murder victim named Huey Cox from Little Rock, Arkansas, believed that the man charged with the crime was innocent. Vidocqians agreed. Two of them provided expert testimony at the trial and the case was dismissed.

Almost 30 years have passed since then. The Vidocq Society helped solve cases like the Arizona Canal Murders and family annihilator John List. The group stresses that it doesn’t want fame or glory and, indeed, often there is none. The society laments that not enough investigators are actually aware of their services and would like a bit more attention if only so that it can work more cases and continue the detective legacy of Eugène Vidocq.