By Arnaldo Teodorani

A peaceful, unnamed town is taken over by an unnamed Army. The invaders arrive by surprise, aided by the treason of an insider: the scheming shop keeper Corell. The traitor seeks recognition from the new Masters, an appointment as new Mayor, but he is despised and put to the side both by the occupiers and the townsfolk.

The locals, under the moral leadership of Mayor Orden and the town doctor, gradually wear down the morale of their enemies. At first with passive resistance, gradually evolving into sabotage and the killing of soldiers.

This is the plot premise of ‘The Moon is Down’, a novel by celebrated American writer John Steinbeck. The novel was published in 1942 as an explicit tool of propaganda: it was translated into several European languages and distributed clandestinely across occupied Europe, where it inspired local resistance movements against the Axis. After the War, King Haakon the VIIth of Norway awarded Steinbeck a medal for his service.

‘The Moon is Down’ does not mention any location, nor the nationality of the characters. But the inspiration is clear: the German occupation of Norway. And the man who inspired Corell, is one of the most infamous traitors of all time: Vidkun Quisling, the man who sold his country to the Reich.

Vidkun the Ambitious

Vidkun Abraham Lauritz Jonssøn Quisling was born on the 18th of July 1887, in Telemark, Norway, the son of Lutheran minister and well-known genealogist Jon Lauritz Quisling.

In his youth, not interested in continuing a line of eight consecutive pastors, he decided to join a military academy instead. In the 1920s, with the rank of Major, Quisling was sent to Russia as a military attaché to the Norwegian Embassy. During his mission, he worked with Fridtjof Nansen, a well-known explorer, diplomat and recipient of the Nobel peace prize. The two documented the terrible famine gripping the Soviet population as a result of the Civil War and early Leninist reforms, and also participated in the relief effort.

This experience left a deep impression on him: a distrust and fear of Communism, and the consequences of a mismanaged socialist state.

He also collaborated with the British, helping to mediate with Moscow on behalf of their interests, and this earned him an appointment as CBE – Commander of the Order of the British Empire.

Upon returning to Norway Quisling decided to leave behind the military career for a political one. He served well with the Agrarian Party and was appointed Defense Minister, a post he held from 1931 to 1933.

In those years the Great Depression did not spare Norway. As in many other countries in Europe, the economic crisis brought about the spectre of political violence. Ever more fearful of a communist takeover, in June 1931, Quisling sent the Army against a union strike. His, and the Government’s heavy-handed tactics did not gain much support.

Eventually the government fell in 1933.

Quisling had ambitions to create his own party and gain power. Looking for inspiration, he looked to Germany.

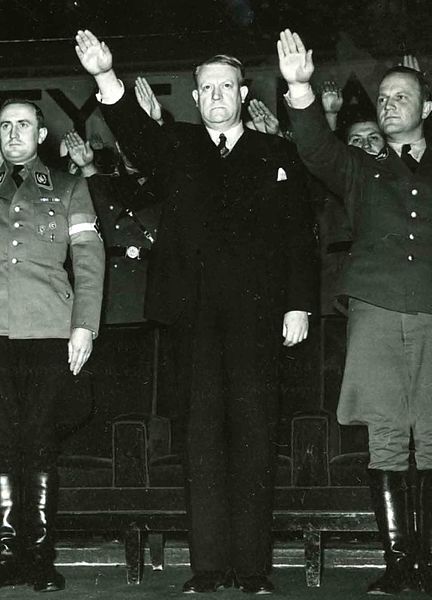

On the 17th of May Vidkun Quisling and state attorney Johan Bernhard Hjort formally founded the Nasjonal Samling or National Union. It was modelled after the ruling parties in Germany and Italy, adopting their trappings: members used the Roman Salute; they formed a paramilitary guard, called the Hoerd, decked in uniforms adorned with eagles. Even the party emblem was a swastika-like symbol.

The National Union’s programme was decidedly nationalistic and anti-Communist. It included a total ban on strikes, the elimination of unemployment and the sterilisation of undesirables. There were three main differences compared to its Nazi inspirators:

One, Quisling and the National Union never adopted socialism, an ideology which was at least at the roots of the ruling parties in Berlin and Rome.

Two, Quisling never made anti-semitism a part of his plans.

And three, National Union tried to retain ties with Christianity.

After six months from foundation the National Union was put to the test, running for parliamentary elections. It was a disaster: the party gained only 2.2% of the votes and 0 seats, doing only a little better than their Communist rivals. At the following elections, in 1936, the National Union did even worse, having alienated much of their Christian electorate.

But not everything was going wrong for Quisling. While attending a conference in the German port of Lubeck, he met Alfred Rosenberg, leading ideologist and foreign policy advisor to Hitler. Rosenberg saw some potential in Quisling and introduced him to several military and political top brass in Berlin.

The ties with his future masters were being established.

Vidkun the deluded

After the start of War in Europe in September 1939, it became very clear to Nazi leadership that for a sustainable war effort they needed more iron and more ships. This was Quisling’s opportunities: Norway could offer both. In December 1939 he returned to Berlin and made a proposal to Rosenberg: he would stage a coup d’etat in Oslo, install himself as Foerer of Norway and invite a German landing.

In support of the plan Quisling offered to Erich Raeder, commander of the Kriegsmarine, details on naval agreements between the Norwegian fleet and the British Royal Navy.

On the 14th and 18th of December Quisling met with the Fuehrer himself, who granted German military support for his coup. In Quisling’s schemes, the German military presence would not be an occupation, rather a garrisoning of his country to deter an Allied landing. Unbeknownst to him, the German High Command intended to take over Norway much earlier than he expected.

On the 3rd of April 1940 Quisling travelled to Copenhagen for a meeting with German secret services, during which he handed over more military intelligence.

6 days later, Germany invaded. Quisling was taken completely by surprise, but he took some initiative and decided to proceed with his coup.

Seizing the Public Radio offices, he proclaimed himself Prime Minister and asked for Norwegians not to resist the Germans, who were there to protect the country from an Anglo-French invasion. The invaders immediately recognised his collaborationist Government. But King Haakon VIIth of Norway was not of the same opinion. He declared Quisling’s government to be illegitimate and fuelled the resistance against the Wehrmacht, even after his eventual escape and relocation to Britain.

Germany invades

According to WWII lore, German commander General Nikolaus von Falkenhorst prepared the invasion of Norway in a single afternoon, with only the help of a travel-guide book.

The invasion started on the 9th of April, opposed by both the Norwegian and British Royal Navies. They opposed the German landing fleets heading for Bergen and Trondheim, succeeding in sinking 12 German vessels. But Luftwaffe air superiority convinced the British Admiralty to cancel further attacks on German landings at Bergen.

In the meanwhile, the Norwegian army was preparing to fight the invaders. To a demand for surrender, the Norwegians replied

“We will not submit voluntarily: the struggle is already in progress.”

However, the Norwegian army was ill prepared. Units moved inland to take advantage of the rugged interior, but the German progress was fast.

By April 20th, eleven days into the campaign, the German army had advanced 180 miles from Oslo.

The first British troops, led by Major-General Mackesy had landed at Harstad, Lofoten Islands off Narvik, on April 15th, a strategic port for the shipment of iron ore.

This force was ill-prepared and ill-equipped, meaning Mackesy took its time to finally move to Narvik in May. Meanwhile, the Norwegians had to fight it alone against Germany’s skilled mountain troops of General Dietl.

A second landing expedition at Trondheim, supported by Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill, had been cancelled, and replaced by smaller forces north and south of the city. The British – alongside French and Polish forces – clashed with the Germans, with heavy casualties on both sides.

But the expedition was doomed for failure. The troops involved had little to no air nor artillery support, plus they had no training of mountain warfare in a cold climate – unlike Dietl’s units.

On the 28th of April the British commander in Trondheim, General Paget, ordered an evacuation. This is when also our friend Adrian Carton de Wiart made his escape – check out our Biographics on him if you haven’t seen it yet.

After Trondheim, the forces in Narvik were left to hold back the Germans, but by the end of May the British Cabinet decided for a total retreat. Losing the whole expeditionary force to the Germans would have spelled disaster, in terms of loss of men, equipment and morale.

King Haakon of Norway embarked with his government on June 7th, heading for Britain. By the 9th of June the campaign was over.

The Norwegians had suffered 1,335 losses, killed or wounded, 2% of their small army. The Anglo-French and Polish allies lost a total of 2,402 soldiers, and the Germans 5,660.

These may appear as a small campaign compared to others of WWII. But the Norwegians and their allies held out for two months against a German invasion, longer than any other country except for the Soviet Union.

The campaign had major political consequences in London, with the resignation of the Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain and the appointment of Winston Churchill.

But what of the consequences for Vidkun Quisling?

Vidkun the Puppet

While the fighting raged on, the Germans realised that Quisling – despite his reassurances – had lost control of the situation, and the country was far from being pacified. The leader of National Union was eventually side-lined, and the Germans installed a trusted man in Oslo: Josef Terboven, appointed Reichskommissar for Norway on the 20th of April 1940.

Quisling’s plan was crumbling. He had a grand idea of him as the leader of an independent Norway , albeit under German military protection. The appointment of Terboven would put his country under direct German control.

After the capitulation in June, the parliament was dissolved. In August Norway became part of the III Reich.

But Quisling was not completely out of the picture yet. Terboven saw some use for him, at least as a local figure head. The kommissar installed Quisling as the head of a puppet collaborationist government and he proceeded to form a Cabinet in autumn of 1941.

But it was clear that the one pulling the strings would be Terboven all along: he proceeded to issue a series of proclaims, all of which were approved and counter-signed by Quisling. These reforms included the consolidation of One-party rule, the revocation of freedom of speech and the introduction of rationing.

In the same year Quisling and Terboven welcomed a visit from Heinrich Himmler, who had come to oversee the creation of the SS Nordland division. This was composed of Norwegian and other Scandinavian volunteers who pledged their allegiance to the Reich and fought under German officers.

Shortly afterwards, on the 21st of June 1941, the invasion of the Soviet Union began.

Also on this occasion, Quisling had grand plans to shine and to prove his commitment to the struggle against Bolshevism. His idea was to create a legion of volunteers to support the German war effort against the Soviets.

But Terboven was quicker and beat him to it. He created a unit of volunteers, similar to SS Nordland, but larger in scale. A skilled politician, the Reichskommissar placated Quisling by reassuring him that the new legion would swear allegiance to him, rather than any German authority. The volunteers would also be allowed to wear Norwegian uniforms, have their own officers, and would see action only on the Finnish front.

Quisling had no choice but to play along and he urged all Norwegians to join. The legion counted 1200 recruits in total, many from the Hoerd, Quisling’s own paramilitary force.

Eventually, Terboven pulled the rug under Quisling: the volunteers were issued SS uniforms, were made to swear an oath to the Fuehrer and were sent to the toughest spots of the main Russian front, including the siege of Leningrad. After suffering heavy losses, the remaining soldiers displayed poor discipline and fighting spirit – and who could blame them – at least according to the SS High Command.

The legion was eventually disbanded. This spelled another failure for Quisling. His idea of contributing to the direct fight against communism had been first hijacked, then it had ended in defeat. What’s worse, his already thin base of supporters had been depleted by the onslaught of the Eastern Front.

The Home Front

The account we painted so far shows as if Quisling was the only Nazi sympathiser in Norway at the time. The reality is very close. Novelist and journalist Arne Skouen, a former member of the resistance, in fact estimates that only 2% of the population were supportive of Quisling and the Germans. But the Norwegian Prime Minister could count on the support of some heavyweights, most notably novelist Knut Hamsun. One of the giants of Norwegian literature, Hamsun had won the Nobel prize for literature in 1920. In the mid-30s his support of the Nazi party became increasingly vocal, to the point of donating his Nobel medal to Joseph Goebbels. At the beginning of the invasion, one of his articles read:

“Norwegians! Throw down your rifles and go home again. The Germans are fighting for us all, and will crush the English tyranny over us and over all neutrals!”

Out of the remaining 98% who did NOT like Quisling, many were involved in the resistance against the occupiers. Sometimes this manifested in actions of civil dissent, but then escalated into acts of sabotage and assassinations. These were coordinated by the Milorg, or Home Front, a resistance movement with 40,000 members at its peak.

In addition to the Home Front activities, ordinary citizens did everything in their power not to yield to the occupation. It became common on public transport to stand up so as to avoid sitting next to a German or a known collaborator. The Germans took this so seriously to issue a decree prohibiting to stand on public transport if seats were available.

An underground newspaper describes very clearly the purpose of civil dissent tactics:

“What the Germans suffer most from here in Norway is the coldness they feel from the people, and their exclusion from contact. Let them feel this chill to their very marrow.”

Underground press was incredibly active, peaking at 300 different newspapers and magazines. The Government retorted with a 1942 decree that announced the death penalty for perpetrators of anti-Party sentiment, even in private writings such as diaries.

As the Norwegians tried to distance themselves from the Germans, the Germans were trying to get very close, especially to Norwegian women. One official SS document stated

“(it is) expressly desirable that the German soldiers conceive as many children as possible with Norwegian women, regardless of whether it is within or outside of the bonds of matrimony.”

This was part of the Lebensborn programme, whose aim was to breed as many Aryan children as possible. In Norway 12,000 children were born to these unions, some consensual, most forced by the fear of consequences for not complying.

Sadly, women involved with German officers, did not have the sympathy of their fellow citizens and could get their heads shaved or be branded with swastikas.

This hostility continued even after the war: many of these 12,000 children were ostracized and often sent away. Interesting fact: one of them fled to Sweden to escape this fate and achieved worldwide fame with her art. You may know her as Frida, from ABBA.

Set Norway Ablaze!

Several young men and women from the Home Front escaped to Britain, where they were recruited by the Special Operations Executive or SOE. This army of secret agents, commandos and saboteurs had been instituted by Winston Churchill with the mission to set Europe ablaze – in other words harass German occupation forces throughout continental Europe.

Several young men and women from the Home Front escaped to Britain, where they were recruited by the Special Operations Executive or SOE. This army of secret agents, commandos and saboteurs had been instituted by Winston Churchill with the mission to set Europe ablaze – in other words harass German occupation forces throughout continental Europe.

The first operation of the Norwegian SOE commandos took place on the 21st of March 1941. Their target: the Lafoten islands, home to fish oil tanks needed for the production of explosives. The operation was a success, especially from a propaganda point of view. A newsreel of the time shows the commandos sending a mocking telegram to Hitler from the islands:

“Herr Hitler

Reference you last speech I thought you said that whenever British troops land on the continent of Europe, German soldiers will face them. Well, where are they?”

The same newsreel shows the rounding up of ‘Germans and Quislings for interrogation’. Quislings meaning local collaborators of course: it is telling how already at this stage of the war Vidkun Quisling’s name had become a synonym for traitor.

On the 1st of February 1942 Vidkun Quisling was appointed as Head of State, in addition to being Head of the Government, which sounds like an empty, ceremonial title, bestowed to keep him happy. He even had his head on a stamp! But the official head of State was still King Haakon and the reins of the government were held by Terboven.

Throughout 1942 the commando raids in Norway continued, mutually supporting an ever-active Home Front. Their most famous action was the destruction of the Telemark plant, a research facility for the production of heavy water – part of Germany’s research effort to develop nuclear weapons.

A little known fact is that a previous raid by an all-British team had failed, with six commandos being captured. Quisling, humiliated by the successes of the SOE and the Home Front, and urged by Terboven, authorised their execution. These were formal POWs, uniformed British soldiers, not spies or ‘bandits’ – please note the air quotes. Their execution was a war crime according to the Geneva Convention.

In the same period Quisling imposed – or simply authorised – measures to enforce harsh martial law on the population. One of these measures was the forced registration of all Jews in June of 1942.

In September, all Jewish property was confiscated. On October 25, 1942, Jewish men over the age of 16 were sent to Auschwitz, followed by women and children on November 25. Of the 770 people deported, 740 were killed in the extermination camps. Only 12 returned after the war.

Curtain Call

Quisling went from cruel blunder to cruel blunder. In 1943, as head of state he formally declared war on the Soviet Union and instituted mandatory conscription. 75,000 young Norwegians were called up to arms: many served in the ski units in Finland, but the majority were sent to work for the German war effort, as part of the compulsory labour service.

Compulsory labour was extended to women in 1944. When a popular chief of police, Gunnar Elefson refused to prosecute two girls who had dodged this unfair draft, Quisling demanded that he be put to death.

These efforts to ingratiate party leadership were all the more futile, as it was clear that the Allies were winning the war.

On the 18th of October 1944, Soviet troops crossed the border with Norway, in the Finnmark county. This was the first page to the last chapter of Vidkun Quisling’s sad existence of failed ambition and treason.

The Soviets were not interested in pushing southwards. They established instead a bridge head at Soer-Varanger and Kirkenes, where Norwegian soldiers under the government in exile staged a landing.

In January 1945 Quisling was invited to Berlin to meet with Hitler. During the meeting he proposed a desperate plan: he wanted Norway to regain its independence, in order to form an alliance of Nordic and Germanic people. He also proposed to the Germans to build a “Fortress Norway” – in other words: use his own country to stage the last stand of the regime against the Allies. After all, Norway was now home to 400,000 German troops.

Both proposals, unsurprisingly, were rebuffed.

After Hitler’s suicide on the 30th of April, Admiral Karl Doenitz succeeded him as Fuehrer. One week later, Doenitz summoned Terboven. Knowing him to be a fanatic, he dismissed the Reichskommissar, handing over duties to General Boehme.

On the 8th of May, German forces in Norway capitulated. The Home Front immediately secured control of the country. On the same day, Terboven blew himself up with a hand grenade.

On the 9th, Norwegian police arrested Quisling in his Oslo mansion, called ‘Gimle’. According to Norse mythology, this was the home of the survivors of the Ragnarok, the twilight of the Gods, the end of times.

Quisling was put to trial with other National Union collaborators. His charges included treason, war crimes, crimes against humanity and embezzlement.

The prosecuting attorney asked him if he had, in his speeches, expressed the viewpoint that

“the Jews are guilty of a number of the misfortunes that have stricken the world”

Quisling did not flinch:

“Yes, that is my absolute conviction”

His initial indifference to anti-semitism had obviously changed during the war. All the evidence was against him. Quisling’s line of defence was that all he had done, he did it to protect Norway from German rule. But proof of his secret meeting in Denmark, one week before the invasion, sealed his fate as a traitor.

Vidkun Quisling was executed by firing squad on the 24th of October 1945.

The Moon is Down

What is the legacy of Vidkun Quisling? He left no children and his name is now synonymous with collaborator, with a traitor who sells his country to the enemy. His career may have started with the intention of protecting his country against Soviet threat, but when he made contact with the Germans, all he wanted was recognition and power. With his incompetence and false promises, he alienated his German allies, with his fearful ruthlessness he alienated his own Country.

The irony is that even without his scheming, Germany would have probably invaded Norway anyways, its resources were just too precious to their war effort. What would have been of him in that case?

Let me go back to Steinbeck’s novel, the one I mentioned at the beginning. In it, Mayor Orden is forced by the invaders to cooperate: they want him – not the traitor Corell – to be the front of their decrees and orders, to become the legitimate face of their power. But he refuses to cooperate, if the soldiers want to play dirty, they will have to do it on their own.

When the resistance intensifies, and the officers threaten reprisals, the Mayor refuses to put an end to it, whatever the consequences.

Maybe in another circumstances Vidkun Quisling could have been an Orden. In our History, he chose to be a Corell.