They say that history is written by the victors, and, in the case of the Gallic Wars, this was literally true – the main source for this conflict between the Romans and the Gauls was the general who triumphed, none other than Julius Caesar himself. After he had won the war, Caesar returned to Rome to enjoy a well-deserved celebration, but also found time to write down his account in Commentarii de Bello Gallico aka “Commentaries on the Gallic War.” So don’t be surprised if the retelling is a bit biased towards the Romans.

On the other side, the Gauls were hindered from the start by the lack of a unified leadership. Being a loosely formed amalgamation of different tribes, they didn’t always play nice together. It took the strength, vision, and charisma of one man to unite them against the Roman Republic, but despite a valiant effort, it was too little, too late to turn the tide of war.

But still, his legacy lives on as a hero of France and a universal symbol of defiance against a bigger, stronger oppressor. And his name was Vercingetorix.

The Gauls Rebel

First, a bit of background on what started this whole kerfuffle. The region known as Gaul occupied what is mostly present-day France, Belgium, and Luxembourg, as well as parts of Germany, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and a bit of Italy. Although all sorts of tribes inhabited this region, the Romans lumped them broadly into three categories: the Belgae, the Aquitani, and the actual Gauls, who called themselves Celts in their native tongue. Geographically, they were separated by the rivers Seine, Marne, and Garonne, and culturally, they were separated by language, laws, and customs.

The trouble started around 58 BC when a Gallic tribe called the Helvetii began migrating south in order to escape Germanic tribes that were trying to muscle in on their lands from the north. Unfortunately for them, the journey south brought them into Roman territory – specifically, a province called Transalpine Gaul and its governor, a general by the name of Julius Caesar. The Helvetii asked for permission to pass through Roman lands and were denied, and, even though they intended to go around them, Caesar attacked them anyway on the pretense that they were a threat to Rome, even just by being near its borders.

Truth be told, there’s probably nothing the Helvetii could have done to avoid conflict. Caesar had grand ambitions in mind to conquer all of Gaul, and the arrival of the Helvetii was just the excuse he needed to go to war. He was one of Rome’s hottest rising stars. Thanks to an alliance with Marcus Crassus and Pompey known as the First Triumvirate, Caesar had secured for himself no less than three governorships at the same time – Transalpine Gaul, Cisalpine Gaul, and Illyricum. Governing even two provinces simultaneously was a rare event. He started with four legions under his command and used his own money to recruit two more. It was clear that he had set his sights high and was ready to strike.

After Caesar defeated the Helvetii at the Battle of Bibracte, other tribes followed. He was winning and, in 55 BC, he even took the time to cross the Channel into England just to have a look-see. It wasn’t until 54 BC that Caesar ran into his first stumbling block when a Belgic leader named Ambiorix led a revolt against the Romans. It didn’t succeed, but Ambiorix became a national hero for Belgium in a similar way to how Vercingetorix became one for France.

Anyway, although Ambiorix had been defeated, he inflicted heavy casualties on the Romans, so that in 54 BC, Caesar set out to subjugate Gaul completely and was even more merciless in his attacks. Eventually, he announced that Gaul was now a Roman province and that all those living there must abide by Roman laws and religion. Finally, this was the step-too-far that made the Gauls understand that, in order to stand a chance against the Romans, they would have to unite under the leadership of one man…Vercingetorix.

Becoming Leader of the Gauls

It was the winter of 53 BC. Caesar had to return to Rome to do some Roman stuff, leaving his army to spend the winter in Gaul. Meanwhile, some of the Gallic chiefs took advantage of his absence and had a super-secret meeting at the behest of the charismatic leader of the Arverni tribe – Vercingetorix. We’d like to give you some more personal info about him, but there’s not a lot available since it was the Romans who wrote about him, and they only bothered once he became a nuisance. All Caesar tells us about Vercingetorix’s past is that he was the “son of Celtillus, an Arvernian youth of supreme influence (whose father had held the chieftainship of all Gaul and consequently, because he aimed at the kingship, had been put to death by his state).”

Vercingetorix tried to warn everyone that they did not stand a chance against the Romans alone, so they had to fight as one. Initially, this wasn’t received very well. Again, Caesar informs us that Vercingetorix’s ideas got him banished by the chiefs, including his uncle Gobannitio. They felt that their only shot was to play nice with the Romans, whereas a revolt would spell certain doom.

But Vercingetorix was not deterred, and, using the small contingent still loyal to him, he traveled from place to place, urging everyone to take up arms in the name of liberty. As we said, he was quite a likable guy, so Vercingetorix began amassing a sizable army. Afterward, he sent messengers to other Gallic tribes, telling them to join his cause. He ensured the loyalty of the other tribes by using the Roman tactic of demanding hostages to keep the rest in line and by enacting strict and ruthless discipline – minor offenders had an ear cut off or an eye gouged out, while serious crimes were punished with death by fire.

Many tribes sided with Vercingetorix because they understood the threat posed by the Romans. We’re not going to mention them all because it would just be a list of hard-to-pronounce names. Some of them joined more out of fear and intimidation than willingness, but whatever got the job done.

Inevitably, word of the Gallic chieftain who was rallying all the tribes under his banner reached Caesar in Rome. It was still winter, and he didn’t have access to his main army, but the Roman general had no choice – he had to march on Gaul.

Food Fight

Vercingetorix began the war at an advantage. He laid siege on the town of Gergovia, which belonged to the Boii, a Celtic tribe allied with the Romans. He knew that Caesar needed time to round up his army. Plus, because it was winter, food was scarce, so the Roman leader also required provisions to feed his soldiers if he didn’t want them to starve to death before the fighting even began. And there was the added benefit of showing the other Gallic tribes that siding with Rome would not keep them safe.

Caesar understood his plan of attack and, indeed, feared that this Arvernian upstart might cause all of Gaul to revolt against him. His answer had to be swift and decisive, but, again, as many military leaders learned across history, an army marches on its stomach. Supplies were his biggest concern at the moment, so on the way to Gergovia, Caesar took the time to lay siege on several towns belonging to revolting Gauls to confiscate their provisions. This served the dual purpose of obtaining food but also ensuring that he wouldn’t have to deal with enemy troops attacking from behind. First, there was Vellaunodunum, then Genabum, and lastly, Noviodunum.

While Caesar was still besieging that last town, word reached Vercingetorix that the Romans were close, so he decided to lift his own siege of Gergovia and meet them head-on. Caesar, however, wasn’t yet prepared for a face-off, so he avoided the Gallic army and made his way to Avaricum, the largest and richest settlement in the area.

This made Vercingetorix realize that Caesar was wary of a pitched battle, so he reconsidered his strategy. He pivoted to guerilla warfare, basically intending to starve the Roman army. As Caesar himself admitted:

“By every possible means, they must endeavor to prevent the Romans from obtaining forage and supplies. The task was easy because the Gauls had an abundance of horsemen and were assisted by the season of the year. The forage could not be cut; the enemy must of necessity scatter to seek it from the homesteads; and all these detachments could be picked off daily by the horsemen.”

Vercingetorix went even further and began burning down homesteads and towns belonging to friendly Gauls just so Caesar wouldn’t have anything to plunder. Although drastic, he reasoned that the Romans would take them, anyway, and at least he didn’t slaughter or enslave the people who lived there.

The tide turned at Avaricum. Caesar arrived first and laid siege, but this town was well-fortified so it wasn’t as easy to conquer as the rest. Vercingetorix arrived later and made camp near Avaricum, but steadfastly refused to engage Caesar in battle, despite pleas from other chieftains, because he believed that the terrain was disadvantageous to them and that the Romans were on the brink of starvation. It got to the point that Vercingetorix was accused of treason, but he successfully defended himself with a rousing speech and by producing a few Roman hostages who admitted that they were getting ready to lift the siege because they desperately needed food. Vercingetorix concluded his defense by saying:

“These are the benefits you have from me, whom you accuse of treachery, by whose effort, without shedding of your own blood, you behold this great victorious army wasted with hunger; while it is I who have seen to it that, when it takes shelter in disgraceful flight, no state shall admit within its borders.”

Fine speech from Vercingetorix, but he got a little too cocky. He had a decent chance here to crush Caesar, and he didn’t take it. Instead, the Romans eventually managed to subdue Avaricum, thanks to their superior knowledge of siege warfare. It took them 25 days, but they built towers tall enough to scale the town walls. Then they waited another couple of days for the opportune time to strike, which came during heavy rain when visibility was reduced and the guards on the wall were less than vigilant.

The attack was sudden, violent, and merciless and caught the people inside Avaricum completely off guard. Nobody was spared. Out of approximately 40,000 people, “scarcely eight hundred” managed to flee Avaricum and make it to Vercingetorix’s camp.

The next day, Vercingetorix had to concede defeat, but he wasn’t as broken up about it as you might think. For starters, he initially wanted to burn down Avaricum just like he did other towns, but was persuaded against it by other chieftains. And he reasoned that the Romans did not win by valor in the field, but by “a kind of art and skill in assault” which the Gauls were unfamiliar with, and that, inevitably, the two sides would have to meet in proper combat and that’s when they’ll see who’s the boss.

Again, these arguments were enough to appease the other Gauls. Even though the Roman army had won the battle and was now well-supplied with food, the war was far from over.

Victory at Gergovia

His soldiers were fed, and winter was almost over. It was the perfect time for Caesar to press the attack and get rid of Vercingetorix forever, but other matters needed his attention. An important Gallic ally called the Aedui was having a succession crisis and needed Caesar to make the final call on who would be the new chieftain. As much as Caesar hated leaving unfinished business, especially when he had the advantage, he understood the perils of internal dissension, and the last thing he wanted was to lose a powerful regional ally to Vercingetorix. When that matter was settled, Caesar returned to the warpath. He divided his army in two: four legions went with his second-in-command, a guy called Labienus, to take on some of Vercingetorix’s powerful allies, while Caesar himself commanded the other six legions as they marched into Arverni territory, towards the town of Gergovia.

When Vercingetorix found out about Caesar’s movements, he, too, traveled to Gergovia and, thanks to forced marching, got there around the same time. Gergovia was built on a high mountain, so a head-on charge would be risky and difficult for the Romans. Caesar didn’t have sufficient provisions, so a siege was out of the question, too. It looked like the two armies would finally clash in battle, but then…treachery from the Aedui. The new guy that Caesar put in charge of the Gallic tribe, a man named Convictolanis, was bribed by the Arverni to switch sides. He conspired with another guy called Litavicus to turn their army, which was supposed to reinforce the Roman troops, against Caesar.

Thus, Litavicus was put in charge of the reinforcements, and, on the way to Gergovia, he stirred up anti-Roman sentiment by telling his men that two of their beloved chieftains had been slain by Caesar without cause. This was enough to sway the Aedui, but there was one problem – those two chieftains were alive and well, and still on Caesar’s side. In fact, when they heard of this treachery, they rode to inform Caesar, and he felt compelled to act immediately, but more diplomatically this time.

Caesar took his cavalry, abandoned the camp at Gergovia, and rode fast to meet the Aedui, but with strict instructions to his men not to kill anyone. Once the two sides met, Caesar simply produced the two living chieftains and showed the Aedui that they had been lied to, while Litavicus and his co-conspirators swiftly departed to join Vercingetorix’s ranks. The Aedui submitted to Caesar, and he spared them all, ostensibly out of his kindness but, in reality, because he needed their soldiers. Things weren’t going so well at Gergovia, and the troops he left behind were suffering heavy casualties at the hands of the Gallic army.

You would think that Caesar’s arrival with reinforcements would turn the tide of war, but it was not to be. Vercingetorix still had a large army at his disposal, and his horsemen were unrivaled when it came to navigating through the rough terrain surrounding Gergovia. Caesar led a direct charge on the town but was repelled, losing 700 soldiers and 46 centurions. He abandoned camp and left Gergovia. Vercingetorix had won the day.

The Siege of Alesia

The Battle of Gergovia was over, but the war continued, and both Vercingetorix and Caesar had the same concern – securing reinforcements. There were still a lot of soldiers in Gaul, and both men wanted them to fight on their side.

Caesar’s immediate concern was securing the alliance of the Aedui since he knew that Litavicus would keep trying to turn them against him. Then, he planned to regroup with his second-in-command, Labienus, who had been busy fighting the Senones. Unfortunately for him, he was unsuccessful in retaining the loyalty of the Aedui, who ultimately decided they liked Vercingetorix better. Other tribes joined the Arvernian leader, as well, and he sent them out to fight the Gallic tribes who stayed loyal to the Romans, to prevent Caesar from gaining any substantial reinforcements when the next battle was due.

Although, if Vercingetorix had his way, that would not be a while, if ever. His horsemen were faster, better, stronger riders than the Romans. His army was more mobile so Vercingetorix could keep the pressure on with the same guerrilla tactics as before – destroying the towns and the harvests before Caesar could get to them and defeating the Roman army through a war of attrition. Caesar, however, saw this coming and sought reinforcements to counter the Gallic cavalry from an unexpected source – the Germanic tribes across the Rhine.

But then the plan changed – again – as Vercingetorix thought he had found a golden opportunity to defeat Caesar once and for all. He heard reports that the Roman army was marching near the borders of Gaul and Italy. He thought that they were fleeing back to Rome and that one big strike could take them out forever. Unfortunately for him, the Romans were a lot more prepared for a fight than he had anticipated. Vercingetorix attacked with the full might of his army against Caesar’s forces and, although both sides suffered heavy losses, the Gauls were defeated. Vercingetorix gave the signal to retreat and headed for the fortified town of Alesia to regroup where unbeknownst to him, the final step of the war would take place.

Unsurprisingly, Caesar followed him to Alesia, but still hurting from his loss at Gergovia, he had no intention of rushing another charge, so he laid siege, hoping to starve out his enemies in a reversal of roles.

But Vercingetorix had an ace up his sleeve…or so he thought. Before Caesar finished building his entrenchments, the Gallic chieftain sent out his horsemen at night to muster all the remaining forces in the area. Reinforcements were on the way and he wanted to trap the Roman army in a pincer attack.

It was a solid plan, but Caesar simply had the superior military mind and anticipated it. He built parallel fortifications on the other side of his army to defend him from a rear attack. Now, the question raised was what would happen first – would the Gallic reinforcements arrive or would the people inside Alesia starve to death?

It was the latter, as it turned out. The town’s food supplies dwindled and some cruel choices were made. Vercingetorix and a council of chieftains ruled that everyone who was “useless for war” due to their health or age should be cast out of Alesia. Basically, all the elders, women, and children were told to leave their own homes to stop being a burden. But, of course, the town was surrounded by the enemy army, so the Alesians actually went to the Romans and begged to be taken as slaves and given food, but Caesar steadfastly refused to break his fortifications for anything. So the people of Alesia were stuck in no man’s land, slowly starving to death between two armies who didn’t want them.

Defeat & Death

As heartless as this strategy was, it worked for Vercingetorix. His army held the town until reinforcements arrived from all over Gaul. Caesar named over 40 different tribes that sent soldiers to the fight, estimating that they numbered around 250,000 infantry and 8,000 cavalry. This was likely an exaggeration to boost his own reputation. Remember – it’s Caesar’s personal account we’re relying on but, still, you get the idea – it was a massive battle.

The first attack was the obvious one – both Gallic armies attacked at the same time, trying to overwhelm the Romans from both sides. However, the fortifications held, and they backed off. After that, the Gauls attacked at night, after spending the previous day making ladders and grappling hooks to try to scale the Roman walls. This attack led to heavy casualties on both sides, but once again, the Romans were able to fend them off.

For the third attack, the Gauls decided to strike at an outer Roman camp that had not been placed inside the fortifications because it was located on a steep hill. The charge was led by one of Vercingetorix’s kinsmen, Vercassivellaunus the Arvernian, who took 60,000 Gauls to destroy that camp and prevent it from reinforcing the main Roman army. At the same time, Vercingetorix led another strike against Caesar’s fortifications from inside Alesia.

This was the fiercest attack of the battle, with both sides giving it their all. For a while, the Gauls had the upper hand, especially the group led by Vercassivellaunus. However, Caesar gambled that the fortifications of his main army would be strong enough to withstand Vercingetorix’s attack while he dispatched six cohorts led by Labienus to reinforce the camp on the hill. Eventually, fearing that his men were beginning to waiver, Caesar himself joined the fray, and his presence gave his troops the morale boost needed to push to victory. Many soldiers had been killed. Many had been captured, but the Romans had won again.

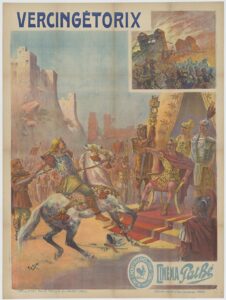

The following day, Vercingetorix was ready to admit defeat. He rode out of Alesia and threw his weapons down before falling to his knees at Caesar’s feet. Technically, the Gallic Wars lasted another two years after this battle, until 50 BC, but that was just clean-up duty. Caesar had won the war at Alesia.

Historian Cassius Dio wrote that Vercingetorix hoped for mercy from Caesar, maybe even a pardon. Whether this was true or not we cannot say, but he certainly did not find it. Caesar had Vercingetorix put in chains and sent to prison in Rome. That is where the Gallic chieftain spent the final six years of his life as Caesar was saving him for a special occasion. Specifically, the triumph that was held in his honor in 46 BC. During the festivities, Vercingetorix was executed in public, some say by strangulation, others by beheading, and Julis Caesar was heralded as one of Rome’s greatest generals. But, as we all know, he had much grander ambitions in mind…