On November 26, 1922, egyptologist Howard Carter entered the tomb he discovered just a few weeks prior. After decades of fruitless searching, he found something more amazing than he could have ever hoped for. When asked if he saw anything inside, he simply replied “Yes, wonderful things.”

Carter had located the tomb of a pharaoh from the 18th dynasty who ruled over ancient Egypt during the 14th century BC. More importantly, though, it was a tomb that had been mostly undisturbed for over 3,000 years.

That pharaoh was Tutankhamun, who ascended to the throne as a young boy and who died when he reached adulthood. His life was short and lacked accomplishments, but that did not matter. For Tutankhamun, death was only the beginning…

He achieved far more fame and glory in death than he could have ever dreamed of while he ruled over the land of the Nile. This young king and his tomb rich with artifacts helped modern society understand ancient Egypt far better than anyone else and, in the process, turned King Tut into the most famous pharaoh in history.

Family Life

Ok, let’s start off with the name. We all know him as Tutankhamun, but things were not really that simple. In fact, according to the royal protocol of ancient Egypt, the full titulary of the pharaohs contained five names. First was their Horus name, the oldest cognomen which dated all the way back to prehistory. In Tut’s case, this was Ka nakht tut mesut. Then came the Nebty name, or the Two Ladies, referring to the goddesses Nekhbet and Wadjet. For Tut, this was Nefer hepu segereh tawy. Then there was the Golden Horus name which, for Tut, was Wetjes khau sehotep netjeru. Lastly, there were the throne name, or prenomen, and personal name, or nomen. They were the ones that pharaohs were typically referred by and are similar to our standard of first name and last name. For our young pharaoh, these were Neb kheperu Ra and Tut ankh Amun. These last two names were always marked distinctly in Egyptian inscriptions to show that they referred to a royal name by encasing them in an oval with a line at one end called a cartouche.

So, if we put it all together and translate it, Tut’s full name would have been “The strong bull, pleasing of birth; One of the perfect laws, who pacifies the Two Lands; Elevated of appearances who satisfied the gods; Lord of the forms of Ra; The living image of Amun.” That’s quite the mouthful so it is not surprising that most people simply call him Tutankhamun, although there are some ancient inscriptions with variants on his name which are even longer.

You would think that is the end of it, but there is actually one more point to make about his name. When he was born circa 1341 BC, his personal name was actually Tutankhaten, meaning “the living image of Aten.” This was because of his father, Akhenaten or Amenhotep IV, who was one of the most controversial pharaohs in history and someone you will likely see on this channel in the future.

The religion of ancient Egypt is still pretty well-known to this day as we’ve all heard of gods like Horus, and Anubis, and Osiris, and, most important of all, the Sun God Amun-Ra. Well, Akhenaten decided to do away with all of that and focus worship on a single deity – Aten the sun disk. The pharaoh even had a new city built dedicated to the god which was intended to function as the new capital of his empire. He called it Akhetaten, modern-day Amarna.

Suffice to say that the people did not take too kindly to this religious revolution. After Akhenaten died, they quickly relocated the capital back to Thebes and went back to their old religion. They even submitted Akhenaten to damnatio memoriae, the practice where they try to completely wipe him from history by erasing his name from all inscriptions. Well, we are talking about him right now so, clearly, they did not do a very good job, but this is why Tutankhamun originally had the name Tutankhaten and why he changed it afterward.

As far as Tut’s mother goes, she is a bit more of a mystery since surviving inscriptions do not make her identity clear. Some egyptologists argue that his mother was Nefertiti herself, the famous Egyptian queen who was Akhenaten’s main wife, or Great Royal Wife, as she was called.

Others are convinced that his mother was an unnamed mummy discovered over a century ago, referred to simply as the Younger Lady. Modern DNA tests support this assertion, but some experts are still not convinced. Some of them argue that the tests are inconclusive due to decayed samples while others opine that the mummy is, in fact, Nefertiti, as her remains have never been found.

The Reign of King Tut

Tutankhamun’s ascension to the throne is somewhat murky because, as we said, later pharaohs tried to make it look like that part of their history never happened. To the best of our knowledge, Akhenaten reigned for 17 years and was followed by two short reigns before Tutankhamun took the throne. Those reigns belonged to Smenkhkare, a pharaoh about whom we know almost nothing, and Neferneferuaten, a female pharaoh who was, most likely, Nefertiti, or one of Akhenaten’s daughters. One or both of them may have reigned as co-regents with Akhenaten prior to his death.

Around 1334 BC, Tutankhamun assumed power. He was still just a young boy, only eight or nine years old, so his decisions were heavily influenced by his advisors. Particularly, one advisor named Ay who served at the king’s court since the time of Akhenaten. It is believed he was the main power hiding in the shadows who actually made the decisions during Tut’s reign and, indeed, after the young king died, Ay became the new pharaoh. He only lasted for a few years before he was succeeded by another one of Tut’s officials, Horemheb, who ended up serving as the last pharaoh of the 18th dynasty.

Tutankhamun’s 10-year reign as ruler of Egypt was unremarkable. The country was still in chaos due to his father’s religious revolution and the young pharaoh, undoubtedly guided by his advisors, renounced his father’s ideas and began restoring things to how they were before the Amarna period. This mostly involved rebuilding temples, monuments, and stelae that were either destroyed or defaced during the time of Akhenaten; abandoning the city of Akhetaten and moving the capital back to Thebes, and changing his name from Tut-ankh-aten to Tut-ankh-amun to show the pharaoh’s devotion to the once-mighty god.

Tut married his half-sister, Ankhesenamun, and together they had two daughters who both died in infancy. Some scholars believe that the queen went on to marry Ay after Tutankhamun’s death, but there isn’t conclusive evidence to support this.

Perhaps the most noteworthy event that happened during that time came courtesy not of King Tut, but his wife. After the young pharaoh’s death, Ankhesenamun may have written a letter to the King of the Hittites, Suppiluliuma I, asking for one of his sons in marriage. The Hittites had long been a thorn in Egypt’s side and, taking advantage of the chaos during the reign of Akhenaten, they grew to be just as powerful. It would have been the first time that the son of a foreign king would have ruled over Egypt and, obviously, Suppiluliuma was over the moon with this idea. He sent his son, Prince Zannanza, to marry Ankhesenamun, but he died somewhere on the way. The exact circumstances of his death are not known, although many speculate that he was assassinated on the orders of Ay or Horemheb (or both).

As for Tutankhamun, like we said, his reign was nothing to write home about. The boy king would surely have been relegated to a footnote in the history books were it not for the events that occurred thousands of years after his death in 1325 BC.

Death Is Only the Beginning

We now leave ancient Egypt and travel over 3,000 years into the future. We are in the same region, which is now known as the Valley of the Kings because it had been used as a burial site for pharaohs and other important ancient officials for almost 500 years. It had been excavated by archaeologists since the early 1800s and, at the start of the 20th century, there was a belief that everything there was to be found had already been found. The man in charge of the excavations, American explorer Theodore Davis, famously ended a paper published in 1912 with the words “I fear that the Valley of the Kings is now exhausted.”

Davis died in 1915 and the rights to excavate the valley were bought by an English aristocrat named George Herbert, the 5th Earl of Carnarvon. He had in his employ an archaeologist named Howard Carter who had been digging for him since 1907 but without any tremendous success.

Carter relocated to the Valley of the Kings and resumed his work for Lord Carnarvon but, again, many years went by without any significant discoveries. In 1922, Carnarvon started to feel like Davis may have been right all along and there truly wasn’t anything left in the Valley of the Kings. He told Carter that he would only fund one more season of digging before he abandoned the valley for good.

Carter’s time was running out but, in November of that year, he made the discovery of the century. According to his own journal, the serendipitous moment occurred by accident on November 4th when his water boy stumbled over a stone. Upon closer inspection, that stone turned out to be the top of a set of stairs buried in the sand. Understandably excited, Carter excavated the spot and found that the stairs led to a burial site of great significance based on the royal seals. He wrote to Lord Carnarvon and waited for the arrival of his benefactor before going inside. On November 26, Carter, Carnarvon, and his daughter, Evelyn Herbert, became the first people to enter the tomb of Tutankhamun in over 3,000 years. Almost immediately, the archaeologist realized the magnitude of the find as he saw “everywhere the glint of gold” – statues, cups, beds, and even a throne filled an antechamber which led to another room with a sealed doorway.

At this point, it wasn’t clear yet what Carter had found – was this simply a treasure cache or was there an actual burial chamber waiting for them behind that doorway? They had to wait a bit to get their answer. It wasn’t until February 1923 that Carter was finally able to enter the closed chamber and glimpse, for the first time, the sarcophagus of Tutankhamun. Afterwards, Carter and his team spent the next decade cataloguing, preserving and removing over 5,000 objects that were sitting in that tomb.

Inside the Tomb

The tomb of Tutankhamun which was designated KV62 consisted of four rooms, a corridor, and a staircase. Contrary to what is commonly believed, the burial site was not completely pristine. It had actually been targeted by thieves in the past, it’s just that the looting happened soon after Tut’s burial and Egyptian officials had time to fix the problem. Some of the doors showed signs of repairs and being sealed more than once.

It appears that the tomb was robbed twice. First time, the thief or thieves didn’t get away with much, but they did steal things like oils and cosmetics which were highly prized in ancient Egyptian society. Such items would not have lasted long so, obviously, the theft occurred soon after the objects were placed inside the tomb.

The second occasion was more complex and organized and involved digging a tunnel inside the burial chamber and accessing the treasury. That room was filled with jewelry and, while thieves stole a lot of it, the scene suggested that they had been caught in the act and had to make a hasty getaway which was why they left so much stuff behind. Even with these acts of vandalism, KV62 was still the most complete pharaoh’s tomb ever discovered.

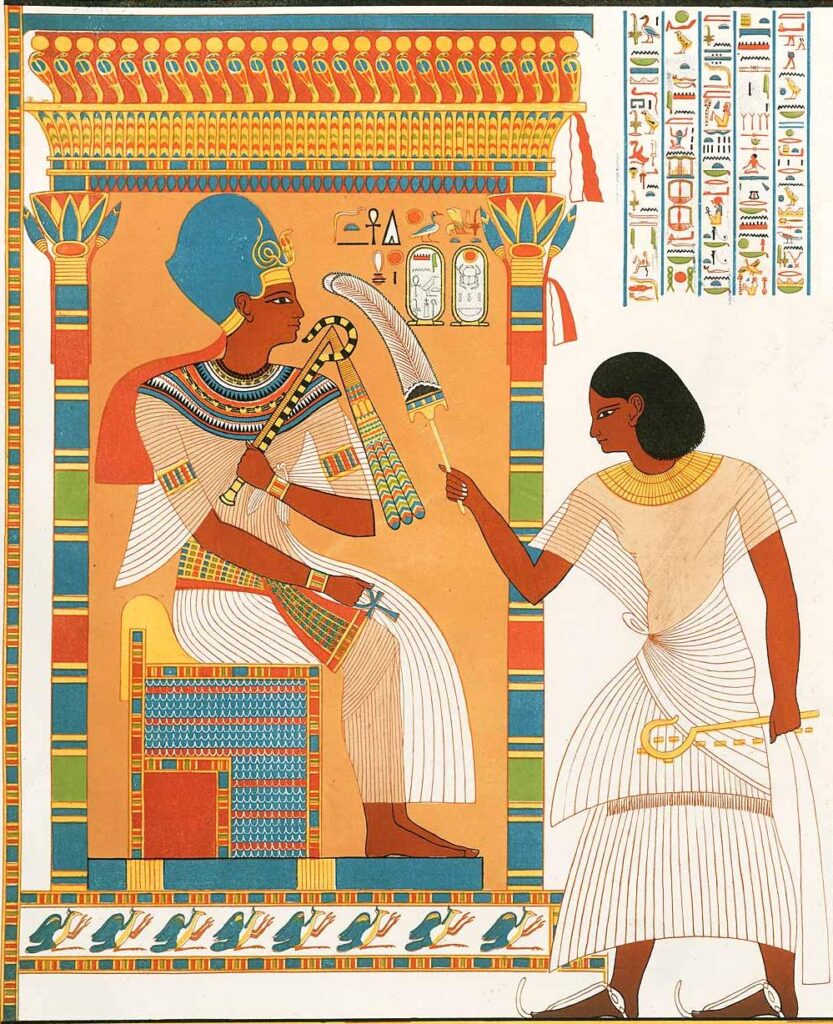

Then, of course, there was the burial chamber, the main event, as it were, which contained the mummy of the boy king. This was the only room that had decorations on the walls which depicted the pharaoh and multiple deities taking part in various ceremonies. The bulk of the room was taken up by four gilded shrines made out of wood. The shrines were each smaller than the last and were placed inside each other like Russian nesting dolls, and inside the smallest shrine, there was the sarcophagus.

Inside the sarcophagus we had a similar situation as the mummy was placed inside three coffins. The outer two were made of gilded wood like the shrines, but it was the innermost coffin which immediately attracted attention as it was made of over 240 lbs of pure gold. Inside the coffin was the pharaoh’s mummy, of course, wearing a gold funerary mask adorned with precious jewels which has probably become the most famous artifact from ancient Egypt.

As egyptologists studied this treasure trove of artifacts, they couldn’t help but notice that this tomb may have never been intended for Tutankhamun at all. Some items showed signs that they previously contained different names which had been erased and “Tutankhamun” written on top of them. This alone could have been explained simply by officials wanting to remove the pharaoh’s original name, Tutankhaten. However, there were plenty of other curious features which suggested that the tomb was originally built for an older man. The most common theory is that it was intended for Smenkhkare, the mysterious pharaoh that ruled for a little bit before King Tut.

For decades, scholars have argued over the possibility of there being more chambers hidden inside KV62. One of them could even contain the elusive resting place of Nefertiti. But this argument seemed destined to remain unsettled since, for obvious reasons, nobody was allowed to start smashing up the burial chamber in search of undiscovered rooms. However, modern technology provided us with an unintrusive solution to the problem – ground-penetrating radar scans.

This technique was not without controversy. The first scans took place in 2015 and detected the presence of open spaces which backed up the idea that there was more to find in Tut’s tomb. However, a subsequent test failed to replicate these results. A third and final scan was performed in 2018 by three different companies which negated the initial findings and detected nothing but solid rock. The Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities has accepted these results and there are no plans to search for more chambers in the near future.

As far as the items inside the tomb are concerned, we are obviously not going to talk about all of them since there are over 5,000 of them. We already mentioned the most important ones, but there are a few more curious objects that merit inclusion. For example, the tomb contained a pair of trumpets, one silver and the other either bronze or copper, which may be the oldest still-functional trumpets in the world. These ancient instruments were actually played once in 1939, on an international BBC broadcast which was heard by approximately 150 million people.

There is one final item to mention which is out of this world…literally. It is a dagger whose blade was made out of iron meteorite. Its exact origins are unclear as the quality metalwork is uncharacteristic of Egypt in Tut’s time so either ancient Egyptians were far more skilled iron craftsmen than we previously thought or the dagger was a gift from another place. Its extraterrestrial credentials were confirmed with the help of a spectrometer that detected high levels of nickel and cobalt, indicative of meteoritic iron.

The Mummy

Studying all the artifacts inside the tomb was all well & good, but what about the mummy? It won’t surprise you to learn that the body of Tutankhamun has been examined and discussed extensively. It probably also won’t surprise you to discover that the young, inbred king wasn’t exactly the peak of good health. In fact, he was frail, disabled, suffered from one or more genetic abnormalities, and probably needed a cane to walk around.

Before we get into any specifics, we should mention that Tutankhamun’s health is the subject of multiple studies and many of them contradict or disagree with each other so there isn’t universal acceptance regarding the pharaoh’s health problems and they also include a fair bit of speculation.

Let’s start with the minor stuff. Tut had several features which were believed to be genetic traits of his bloodline. They included a small cleft palate, an overbite, and larger-than-normal center incisors. He also had an unusually elongated skull shape which, again, was thought to be an abnormality that ran in the family.

Tut had trouble walking and, although it was initially believed this was due to a stress fracture caused by an accident, recent research indicates that he was actually born with a severe club foot. His condition may have gotten even worse as the years went by as he may have also suffered from a degenerative bone condition called Kohler disease. His spine was curved and showed fusion in the upper vertebrae which some believed could have been a sign of Marfan’s syndrome, although this idea was later dismissed by the most recent tests.

The malformation on his leg would have been so extreme that the pharaoh would not have been able to walk without a cane. As proof of this, scholars point to the fact that over 100 walking canes were buried with the young king in his tomb.

There is a reason why not everyone is onboard with this idea and it is because it cancels out one of the main theories regarding Tutankhamun’s death. Some egyptologists are of the firm opinion that the boy king died from injuries suffered in a chariot crash. However, if his foot was as bad as this new study indicates, then it would have been impossible for him to ride in a chariot.

This brings us neatly to our next point – what killed Tutankhamun? There is no mention of his cause of death in ancient records and examining his remains didn’t reveal an obvious answer. For decades, it was believed that Tut’s death came as the result of foul play. X-ray scans performed in the 1960s showed that the young pharaoh had bone fragments inside his skull, indicative of a blow to the head. However, newer tests revealed that the bits of bone ended up there in modern times, when the mummy was removed from its coffin. There were no other signs to suggest a fatal head blow.

Then there is the aforementioned “chariot crash theory” which asserts that Tutankhamun died either due to direct injuries sustained in a chariot crash or from an infection that came as a result of it. Adherents of this idea point to damage done to the young king’s ribs and chest which could be indicative of crushing injuries, plus images in his tomb that depict the pharaoh riding a chariot in battle. Again, opponents of this theory believe these injuries were caused recently while handling the mummy.

The most up-to-date research actually suggests that Tut died from malaria. Tests performed a decade ago found traces of the infection in four mummies, including Tutankhamun. This, compounded with all the other health problems that lowered his immune system, could be the culprit that cut the pharaoh’s reign short. There is no universally-accepted solution, but this is, at the moment, the most prevalent theory.

The obsession with death surrounding Tutankhamun hasn’t really been restricted to his own demise. After all, many other people died after the tomb was opened because they dared to disturb the sleep of the pharaoh. Didn’t they?

Yes, we’ve all heard about the notorious curse of the pharaohs. It has been mentioned since the 19th century, but it was the discovery of Tut’s tomb that made it infinitely more popular and helped it reach the public consciousness. Although, curiously, there is no actual curse inscribed anywhere inside KV62. It was a fabrication of the newspapers. This was more of an Old Kingdom practice, while Tut’s 18th dynasty ruled firmly during the New Kingdom.

There is one suspicious death surrounding the discovery of the tomb, one single death that set off the mania of the “mummy’s curse.”. Lord Carnarvon, the man who funded Carter’s digging, died a few months after entering the tomb. He succumbed to blood poisoning and the newspapers immediately started touting the “curse of the pharaohs.” Since then, anything bad or remotely suspicious that happened to one of the dozens of people involved with the mummy was ascribed to the curse. However, the British Medical Journal actually did a scientific study and found that the life expectancy rate for those people wasn’t higher or lower than the average. It was just that the abnormal cases received much more media attention.

The study also debunked another notion which said that there was a more direct way in which the tomb caused the demise of Carnarvon and others – ancient mold spores which they inhaled and caused damage to their respiratory systems. This didn’t happen, either, and, if it did, it would have killed them a lot sooner, not in months or years.

So you can rest assured that, should you ever disturb the pharaoh’s slumber, you will not be cursed…probably.