“Felicior Augusto, melior Traiano”. According to 4th century historian Eutropius, that was the acclamation used to greet new Roman emperors in his time. It expressed hope that the ruler will be “more fortunate than Augustus and better than Trajan!” The historian lived 200 years after Trajan, but the memory of his reign of prosperity was still very much alive in the hearts and minds of the Roman people.

Trajan was part of the “Five Good Emperors” – five successive rulers who presided over an 85-year period of affluence for the Roman Empire. Of those emperors, we can safely say that Trajan was the best of the bunch. He enacted welfare policies for the poor, restored confiscated properties and undertook numerous construction projects. Within his borders, he brought stability, while outwardly, he led military campaigns which saw the Roman Empire expand to its greatest size ever.

He became the paragon that all subsequent emperors aspired to emulate although none of them reached the same heights. To honor his accomplishments, the Roman Senate bestowed upon Trajan the title of “Optimus Princeps” – “the best ruler”.

Family and Military Life

Trajan was born Marcus Ulpius Traianus on September 18, 53 CE, in the city of Italica. This was located in Hispania Baetica, a Roman province which roughly corresponds to the modern region of Andalusia in Spain. This is, in of itself, significant because Trajan will become the first Roman emperor to be born outside of Italy.

His father was Marcus Ulpius Traianus the Elder, a Roman statesman, while his mother was Marcia, a noblewoman who was the sister-in-law of Emperor Titus. He also had an older sister named Ulpia Marciana who remained very close to her brother throughout their lives. Trajan would often consult her as emperor when making important decisions. Sometime during his reign, he bestowed upon Ulpia the imperial title of Augusta, making her the first sister of a Roman ruler to receive this honor. Trajan extended this love and trust to Ulpia’s daughter, Salonia Matidia, as he himself never had any children. After Ulpia’s death, Trajan had her deified and gave the title of Augusta to his niece.

As a young man, Trajan distinguished himself with his military service. He quickly rose through the ranks, undoubtedly helped by his father’s position and influence. Sometime around the year 86 CE, his cousin, Publius Aelius Hadrianus Afer, died and Trajan became one of the guardians for his two children – his daughter, Aelia Domitia Paulina, and his son, Publius Aelius Hadrianus the Younger. The son would later succeed Trajan to the throne of Rome as Emperor Hadrian. Also during this period, he met and married Pompeia Plotina. Ancient scholars portrayed her as being a kind and intelligent woman. She took an active role during her husband’s reign, sponsoring initiatives to help the poor and improve education. She outlived Trajan by a few years and, when she passed on, Hadrian built her a temple and deified her.

Trajan’s military life is poorly documented. We know that he was successful and well-liked by his fellow soldiers, something that would prove vital to his ascent to power later on. He served as a tribune for 10 or so years, and traveled to Syria when his father became governor there. In 89 CE, Trajan was in command of his own legion and was sent to either Hispania or Upper Germania, to put down a coup against Emperor Domitian. This earned him the favor of the ruler who granted Trajan a consulship in 91.

Domitian

In order to get a proper understanding of Trajan’s rise to the throne, we need a little background on the two emperors who came before him: the aforementioned Domitian and Nerva.

Domitian ended up being the last ruler of the Flavian Dynasty and ancient sources would have us believe that he was a cruel, ruthless, and egomaniacal tyrant. Modern historians tend to disagree, however, and assert that these characterizations of the emperor were part of a concentrated effort to denigrate him after his death.

It is almost certain that Domitian was an autocrat who ruled with an iron fist and instituted a cult of personality around himself, but his totalitarian tendencies were usually focused on one particular group: the aristocracy of Rome. Specifically, he was constantly at odds with the Senate whose powers the emperor curtailed. His policies and propaganda actually made the emperor pretty popular with the people and the army.

Domitian was assassinated on September 18, 96 CE. According to Suetonius, he became “an object of terror and hatred to all” and was the target of a conspiracy organized by his own friends and “favorite freedmen”. The emperor was slain in his chambers where he was stabbed seven times.

Nerva

Nerva was crowned the new ruler of Rome and he immediately began restoring many of the liberties and privileges taken away by his predecessor. Nerva was the first of the so-called “Five Good Emperors” and, as you would expect, he did many things to earn this reputation. He brought people back from exile, put a halt to treason trials and gave a lot of land to the poor. He also instituted numerous policies to save money such as abolishing many sacrifices and spectacles, selling large gold and silver statues commissioned by Domitian and forbidding that any such sculptures should be made in his own honor.

Although Nerva was popular with the people and the Senate, he failed to appease the army where support for Domitian was still strong. The Praetorian Guard demanded that the conspirators who assassinated the previous emperor be executed, but Nerva refused.

A quick side note here to give a little historical context on how important it was for an emperor to have the approval of the Praetorian Guard. Although they began as an elite military unit, they became the emperor’s personal bodyguards under Augustus. From there, they kept growing in size and influence until they turned into the de facto police force of Rome. There have been quite a few intrigues and assassinations where the Guard played a vital role. Maybe we’ll talk about a few of them some day.

On one particularly egregious occasion, the Praetorian Guard killed the emperor and then, effectively, sold the throne of Rome by granting their support to the highest bidder. This happened in 193 CE when they killed Pertinax and accepted an offer of 25,000 sesterces each to make Didius Julianus the new Emperor of Rome. His reign lasted a whopping 66 days before he was also assassinated.

Back to Nerva, there was another problem with his reign – he was old and in poor health. He was 66 years old when he took the throne and had no children or close relatives. The discontent of the army plus the lack of a clear successor pretty much guaranteed a civil war upon his death.

In an attempt to pacify the soldiers, Nerva assigned command of the Praetorian Guard to Casperius Aelianus who served as praetorian prefect under Domitian. This tactic backfired because Aelianus incited the men to get justice for their former emperor. In July or August 97 CE, the Praetorian Guard lay siege to the imperial palace, took the men responsible for Domitian’s death by force and executed them.

Nerva was not harmed, but his authority was in tatters. Only one thing could help him keep his position – naming an heir who was popular with the people, the army, and the Senate. That heir was Trajan.

Rise to the Throne

Trajan’s appointment came just in time. He was named heir in October 97 CE. A few months later, on January 27, Nerva died of natural causes after 15 months as emperor. Trajan, who was governor of Germania Inferior when he heard the news, was in no hurry to get to Rome to start his new career, instead taking a lengthy tour of the empire’s frontiers. Scholars had suggested he did this to ensure he had the loyalty of the soldiers across the Roman domain.

He did see fit to deal with the praetorians who revolted against Nerva, though. He sent for Aelianus and the rest of the mutineers to come to Germany for special employment and there, according to Cassius Dio, he “put them out of the way”.

It wasn’t until the summer of 99 CE that Trajan finally set foot in Rome as emperor. Dio takes the opportunity here to compliment Plotina, Trajan’s wife, who, upon entering the palace for the first time, turned around to the crowd and said “I enter here such a woman as I would fain be when I depart”. And, indeed, according to the historian, she exhibited behavior beyond reproach during the entire reign.

The Dacian Wars

As emperor, Trajan first turned his attention to Dacia, a kingdom that mostly corresponds to modern-day Romania and Moldova.

Dacia had been a nuisance to Rome, on and off, for a few centuries. During the mid 1st century BCE, a powerful Dacian king called Burebista had united all the various tribes under his rule. Caesar was planning to lead a campaign there, but was killed in 44 BCE. However, Burebista was assassinated that same year and the kingdom slowly splintered after his death. It wasn’t until over a century later that it reemerged as a menace under King Duras and attacked the Roman province of Moesia.

Domitian was emperor at the time. He had to respond to this invasion so he launched the First Dacian War. In 87 CE, a Roman army led by General Cornelius Fuscus crossed the Danube and suffered a humiliating loss at Tapae. The next year, a renewed offensive was more successful, but Domitian still had to accept peace on favorable terms to the Dacians because his army was needed someplace else to put down a rebellion. The new Dacian King Decebalus might have declared himself a client of Rome but, in exchange, he received money and craftsmen which he used to improve Dacia’s defenses and arm its soldiers.

For decades, this peace was a bit of an embarrassment for the mighty Roman Empire, especially since the Dacians still liked to carry on border raids from time to time. Cassius Dio described Decebalus as a “worthy antagonist of the Romans”, a king who was “shrewd in his understanding of warfare”, and a “master in pitched battles”. Clearly, Trajan agreed because he saw it necessary to deal with the threat once and for all and restore some of the glory lost during Domitian’s failed campaign.

Trajan got the Senate’s blessing to go to war and, in 101 CE, the Roman army crossed the Danube River once again and invaded Dacia. The Roman Emperor obtained a major victory over Decebalus at the Second Battle of Tapae. A few more minor conflicts followed but, in the end, Trajan decided to sue for peace because he didn’t want his army to get caught in Dacia during winter. This time, though, the terms were considerably in Rome’s favor.

Among other concessions, the Dacians had to build a stone bridge over the Danube which would make it a lot easier for Roman troops to cross the river should they invade Dacia again. This structure, simply known as Trajan’s Bridge, was considered quite a marvel of its time. It was designed by a brilliant Greek architect called Apollodorus of Damascus who would also be responsible for other constructions ordered by Trajan. The bridge only stayed functional for a few decades until Emperor Aurelian destroyed it, but it remained the longest bridge of its kind for over 1,000 years.

There was peace, but Trajan understood that it was only a moment of respite until the Dacians regained their strength. In 105 CE, the two sides went to war again. This time, the fighting was more neck and neck as the Romans struggled to gain a decisive victory. In 106, they laid siege to the Dacian capital of Sarmizegetusa and eventually forced the people inside to surrender by destroying their water supply. Afterwards, the capital was razed to the ground. Decebalus committed suicide instead of being taken prisoner and his head was brought back to Rome.

Half of Dacia was annexed as a Roman province while the other half remained free but consisted of tribes that never united again. The land had rich gold mines which provided a great boost to the Roman economy, not to mention the tens of thousands of slaves who were sent back to Rome.

A few years later, Trajan’s victory in the Dacian Wars was commemorated in a triumphal monument called Trajan’s Column which still stands today in Rome. It is 115 feet tall and has a spiral bas relief which depicts all the important events from the wars. It is, actually, the only source we have for some aspects of the conflict and historians still debate if it is historically accurate or intended more as a propaganda piece.

The Roman emperor also put down his version of the story into writing. Inspired by Commentarii de Bello Gallico, Julius Caesar’s firsthand account of his wars with the Gauls, Trajan wrote De bello dacico. Unfortunately, the book is lost to history except for just one sentence which was quoted in a different work – inde Berzobim, deinde Aizi processimus. It means “We advanced to Berzobis, and then to Aizi”.

Work in Rome

Shortly after his triumph, Trajan had an opportunity to add the Nabataean Kingdom to his empire. This was significantly different from the fights he had with the Dacians. It was already a client-state of Rome and, after King Rabel II Soter died in 106, all it took was to move in two legions from nearby provinces. We don’t know specifics about the conquest, but it seems that the troops encountered almost no resistance. Thus, the Nabataean Kingdom came to an end as it was turned into a Roman province called Arabia Petraea.

The next few years of Trajan’s reign were peaceful and they allowed the emperor to focus his attention on improving things back home. He had 123 days of games and festivities to celebrate his victory in the Dacian Wars. He built and improved roads and bridges such as the 205-mile Via Traiana which can still be partially found on the road between Benevento and Brindisi.

Image: Trajan’s Market

In Rome, he put Apollodorus of Damascus’s talents to good use. The architect designed and constructed a new market, baths and a forum which would become the last of the Imperial fora built in ancient Rome. The only improvement they could have used was a bit more creativity with the names. Predictably, they were called Trajan’s Market, the Baths of Trajan, and Trajan’s Forum. Other constructions ordered by the emperor included libraries, aqueducts, temples, and a renovation of the Circus Maximus which saw it rebuilt entirely in stone.

Cassius Dio mentions in passing that Trajan was the target of several plots against him. He only names one conspirator as Crassus. Obviously, these conspiracies failed and the emperor brought Crassus before the Senate to be punished. What exactly happened to him and his co-conspirators remains a mystery as the historian specifies that Trajan made an oath not to shed blood (by which he meant Roman blood, of course) and that he kept this vow.

The Parthian War Begins

In 113 CE, Trajan entered conflict with the Parthian Empire, a powerful entity located in ancient Iran.

Like Dacia, Parthia had long been a thorn in Rome’s side as clashes between the two domains went back centuries. Also like Dacia, Trajan sought to be the one to solve this problem permanently and enjoy the renown and acclamations that would come with it. In fact, the emperor’s complete, true motives remain somewhat of a hot topic among Roman historians. Some see them as being practical. Trajan wanted to strengthen the defenses of his eastern frontier and benefit from the economic boost of adding Parthia to the Roman Empire. Others believe it was simply in his nature. Trajan was a military man, first and foremost, and would have likely gone on warring as long as he could. And some opine that Trajan wanted to emulate the conquests of Alexander the Great and secure for himself the near-divine status that the latter enjoyed. Whatever the reason, in 113 CE, Trajan marched, leaving Rome, never to return again.

Located between the two empires was the Kingdom of Armenia. Although technically independent, it fell under the hegemony of both Rome and Parthia and both powers had a vested interest in ensuring that the ruler of Armenia was on their side. In 110 CE, the Parthian Prince Axidares was installed as King of Armenia by his uncle, King Osroes I of Parthia, without Roman approval.

On his way to Armenia, Trajan met an embassy from the Parthian king. In an attempt to appease Rome, Osroes had deposed Axidares and installed his brother, Parthamasiris, as new ruler of Armenia and sought Trajan’s approval for this change. Why exactly he thought the emperor would be ok with one brother, but not the other, we don’t know. Trajan was gracious to his guests but mostly ignored their requests and kept on marching.

The conquest of Armenia was quick and bloodless. King Parthamasiris entered Trajan’s camp, took his diadem off his head and surrendered it to the emperor. He fully expected to get it back and become a client-king of Rome in a move reminiscent of what Nero did with King Tiridates half a century prior. Instead, Trajan kept Armenia as a new Roman province and installed a governor to rule. Parthamasiris died soon after and, although the circumstances are not known, some have speculated he was killed on Trajan’s orders.

The Mesopotamian Campaign

In 115 CE, the emperor launched his Mesopotamian campaign, although the exact order of events is unclear from ancient sources. Besides the Parthian Empire, the region was full of small kingdoms and city-states with kings and satraps alike sending gifts and envoys to ensure they obtained the favor of Rome.

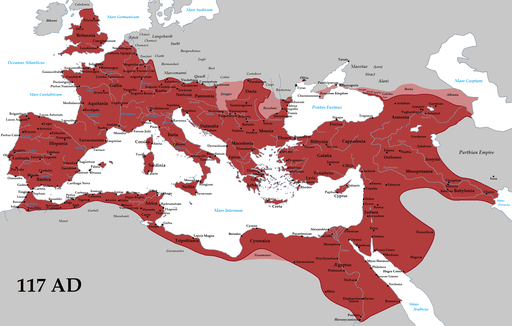

Trajan split his army into divisions that went after multiple targets. He was then able to capture, in quick succession, Adiabene, Babylon, Charax, and Seleucia, culminating with the conquest of the Parthian capital of Ctesiphon. At this point, the Roman Empire reached its greatest size in history.

Cassius Dio writes that Trajan was tempted to march into India, like Alexander the Great did, but concluded that he was getting too old for this thing. Instead, he was content with making a trip to Babylon and offering sacrifice in the house where Alexander died. He did make sure to specify in writing to the Senate, though, that he advanced further than Alexander, although keeping his new possessions proved to be a problem.

When Trajan left, many of the domains he conquered began rebelling and the garrisons that stayed behind were not enough to maintain control. It is also at this time that the emperor’s health started to decline and some historians believe he might have suffered heat stroke while laying siege to the city of Hatra.

To make matters worse, Jewish populations in multiple regions such as Cyrene and Egypt began uprising and Trajan had no choice but to divert armies to deal with these revolts.

Death

Trajan hoped that this would be a minor setback. He left his troops in charge of his generals and set sail for Italy to regain his health. He then planned to return, take command again and settle any conflicts that remained.

That’s not how things panned out. He died suddenly on August 8, 117 CE, aged 63, in the port-town of Selinus in modern-day Turkey. His cause of death remains somewhat controversial. Some sources say he died of a stroke, although both modern and ancient historians made mention of poison.

His succession was also a bit contentious. His cousin Hadrian followed him on the throne, but whether Trajan actually named him as his heir or this was arranged by his wife Plotina after his death remains debatable. One of Hadrian’s first acts was to pull out of Mesopotamia as it became clear that Rome did not have the resources to keep the region.

Trajan might have ultimately failed in his Parthian campaign, but he left behind a cherished legacy that is still celebrated today.