Oda Nobunaga hacked out the stones, Toyotomi Hideyoshi cut them into shape, and Tokugawa Ieyasu set them into place. Three men of different backgrounds, with vastly different personalities, who all worked towards the same goal that many considered too ambitious to ever be achieved – the complete unification of Japan.

Today we finish our coverage of the three “Great Unifiers” with a look at the last member of the trio, the one who actually got to see his dream fulfilled as he ushered in an entirely new era for Japan – the founder of the Tokugawa Shogunate, Tokugawa Ieyasu.

The Hostage Life

Tokugawa Ieyasu was born on January 31, 1543, at Okazaki Castle in Mikawa Province, during the turbulent and violent Sengoku Period of Japan. In case you need a quick reminder of how things worked in the country back then, let’s get you up to speed. The emperor was still around, but he was a powerless figurehead, who mainly played a ceremonial role. For hundreds of years, Japan had actually been run by a military leader called a shogun, who enacted his will through dozens of local lords called daimyos. But during the Sengoku Period, even the shogun had lost most of his authority by allowing the daimyos to become too powerful. At that point, he needed them more than they needed him and the shogun knew that, if some of the strongest daimyos decided to disobey him, there was nothing he could do about it except wag his finger in their direction while giving them a disappointed look.

This power imbalance allowed the daimyos to run wild, as they all poked and prodded their neighbors in pursuit of even more land and power. That’s basically what the whole Sengoku Period was – 150 years of almost-constant civil war between numerous factions, with none of them able to rise above the rest and claim the undisputed title.

Now that we’re caught up, let’s get back to Tokugawa. His birth name was actually Matsudaira Takechiyo, and he was part of the Matsudaira clan based near modern-day Nagoya. As was customary for Japanese noblemen, he changed his name several times throughout his life, but we are going to stick with Tokugawa from the start to make it a bit less confusing.

Although the Matsudaira family claimed descendency from one of the great clans of Classical Japan, by the time Tokugawa was born, they were only a bit player on the national stage. Therefore, if they wanted any serious screen time, they had to latch onto someone with more star power, and that someone was Imagawa Yoshimoto.

When Tokugawa was five years old, his father, Matsudaira Hirotada, struck an alliance with the Yoshimoto clan against the hostile Oda clan. Yoshimoto accepted, but his protection came with a steep price tag – young Tokugawa would be sent to live with him at his castle, as a hostage, just to make sure that his new ally wouldn’t get any funny ideas about double-crossing him.

Matsudaira complied, but his son never made it to Yoshimoto. The leader of the Oda clan, Nobuhide, found out about this little arrangement, so he laid an ambush for Tokugawa’s retinue and took the nobleman’s son hostage for himself. His plan was to force Matsudaira to betray Yoshimoto, or else he would execute his son, but Matsudaira pretty much told him to go ahead and do it. In fact, he’d be doing him a favor, because the sacrifice would show Yoshimoto just how serious he was about their alliance. Whether this was a calculated bluff or “worst father of the year” material, we don’t know, but fortunately for Tokugawa, Oda Nobuhide spared him and kept him as a hostage at his castle in Nagoya for the next few years. People speculate that, during this time, Tokugawa met Nobuhide’s son and the man who would go on to have a tremendous impact on his life, Oda Nobunaga.

During his years as a hostage, the fighting between Oda and Yoshimoto got more and more intense, as both clans vied to become the dominant faction in the same region. When Tokugawa was nine, Yoshimoto laid siege to the castle where he lived and he was given to Yoshimoto as part of a truce between the two sides. Now that he had been rescued and no longer was an Oda clan hostage, the original arrangement could resume – he would become a Yoshimoto clan hostage.

Tokugawa lived at Yoshimoto’s Sunpu Castle until he came of age, but he was allowed to do all the stuff that was expected of a young nobleman. He got married when he was 16, and when his father died, he traveled to the family estate to get confirmed as the new head of the clan, and began raising an army to fight the Oda clan. Now that he led the Matsudaira Clan, Tokugawa entered military service for Yoshimoto, except that he would not be fighting Oda Nobuhide, but rather the new leader of the clan, his son, Oda Nobunaga.

Tokugawa’s time as a retainer for Yoshimoto had both good and bad parts. The bad part was that he backed the losing side. Nobunaga defeated Yoshimoto at the Battle of Okehazama in 1560 and the leader of the Yoshimoto clan was killed in combat. The good part was that Tokugawa himself was nowhere near that slaughter, having been sent to capture and hold a fort in a different part of the province.

With his former master dead, Tokugawa considered all his previous oaths null and void. Wisely, he pledged allegiance to Oda Nobunaga, and together they embarked on a country-wide conquering spree, determined to bring the whole of Japan under their sword.

Oda’s Sidekick

Now had begun Tokugawa’s 40-year-long journey to become the man in charge, because if there was one quality that he possessed in spades, it was patience. It probably came from spending most of his childhood as a hostage, but Tokugawa knew exactly when it was the right time to step aside and when it was the right time to strike. For now, he was eager to prove himself as Nobunaga’s worthiest retainer.

He started off close to home by fighting to unite all of Mikawa province under his banner. This did not prove to be overly difficult, but it was time-consuming. Tokugawa could not rely on reinforcements from Nobunaga for two reasons: one, he was busy with his own battles; and two, he expected his retainers to show that they could stand on their own two feet without Daddy Nobunaga coming in to save the day. Tokugawa spent most of the following decade engaged in combat in Mikawa. In 1567, he received permission from the emperor to officially change his clan name to Tokugawa, claiming to be a descendant of the prestigious Minamoto clan that used to include the imperial bloodline in centuries past. His evidence was sketchy at best and probably would not have held up to close scrutiny but, as we said, the emperor was there just for show, and since Tokugawa had allied himself with the most dangerous man in Japan, who was going to argue with him?

By 1568, Mikawa was under Tokugawa’s control, but he wanted more, so he forged an alliance with another formidable military commander, Takeda Shingen, leader of the Takeda clan. Together, they started going after the territories of Tokugawa’s former boss, Imagawa Yoshimoto. Their union proved to be remarkably effective and, in less than two years, each one had added another province to his domain.

But alliances were fickle during this turbulent period of Japanese history. That whole bushido warrior code thing might as well have been written on water-soluble paper for how strictly it was adhered to. With Takeda growing too much in power, Tokugawa plunged the knife into his back, metaphorically speaking, and broke their alliance. He then entered a new pact with two of Takeda’s enemies: the Uesugi clan and Yoshimoto’s son, Imagawa Ujizane, promising to help them conquer Takeda’s lands, as long as they stayed away from his newly-gained territories. Tokugawa probably intended to cripple the Takeda clan permanently, not wanting another powerful faction so close to home, but for now, he had to put these ambitions to rest because he got the call-up from Nobunaga. It was time to gather his army and join the big leagues because they had a country to conquer.

Tokugawa and 5000 of his best men helped Oda Nobunaga defeat the Azai and Asakura clans at the Battle of Anegawa in 1570, notable not only for featuring the first-ever Oda-Tokugawa tag team but also for Nobunaga’s prodigious use of firearms, which had only been around in Japan for a few decades at that point.

It was a solid start for their alliance, but the sequel proved to be a complete disaster for Tokugawa, like Jaws: The Revenge levels of bad. Takeda did not take his betrayal lying down, so in 1572 he gathered a large army and marched into Tokugawa’s territory, intending to capture his main castle at Hamamatsu.

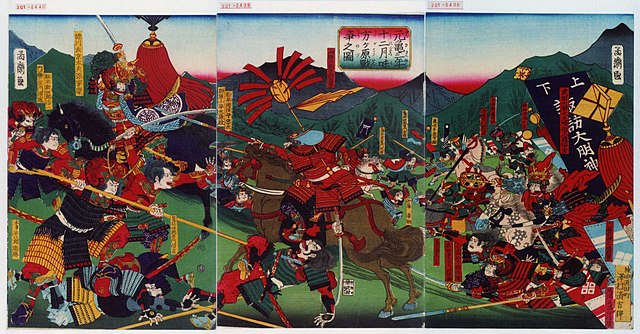

Their battle took place in January 1573, outside of Hamamatsu at Mikatagahara. Tokugawa had around 8000 men, plus another 3000 from Oda. Takeda Shingen had triple that, including a very strong cavalry, plus nobody would deny that he was the superior military strategist given the 20-year age gap between him and his enemy.

Takeda ignored Tokugawa’s forces at first, sending his vanguard to hit Oda’s troops and hit them hard and fast. Chaos ensued among Nobunaga’s forces and they quickly retreated, leaving Tokugawa on his own. Then, superior numbers allowed Takeda to bring back his first line and let them rest while others entered the fray against Tokugawa’s army. It was an absolute bloodbath and Tokugawa’s forces were wiped out completely. According to tradition, he returned to Hamamatsu Castle with only five men.

It was, without a doubt, the most conclusive and humiliating loss that Tokugawa would ever experience, but somehow, he still managed to survive and hold his castle. Whether it was dumb luck, clever strategy, or divine intervention, you be the judge. So as to avoid a full-on panic inside Hamamatsu, Tokugawa ordered the complete procedure for his retreating army – castle gates left wide open, braziers lit, war drums beating, the whole shebang – even though the retreating “army” could fit inside a midsize family sedan. When Takeda’s troops arrived at Hamamatsu and saw this spectacle, they suspected they might be walking into a trap, so instead of charging the almost-defenseless castle right away, they decided to make camp. During the night, a small band of Tokugawa soldiers infiltrated the camp and launched a surprise attack, causing confusion among the enemy ranks. Takeda feared that Tokugawa might have some trick up his sleeve he had not foreseen and that reinforcements from Nobunaga might trap his forces between two armies so, even though he had completely annihilated his foe, he played it safe and lifted the siege and retreated back to his own territory.

Takeda Shingen fully intended to try again later, but that opportunity never came. He was injured in another battle and died just a couple of months later, leaving his clan in the not-so-capable hands of his son Takeda Katsuyori who was definitely not a chip off the old block. He lacked his father’s experience and skill and was soundly defeated by the combined forces of Nobunaga and Tokugawa at the Battle of Nagashino in 1575. He lived for another six years after that, launching minor incursions against his enemies, but the Takeda clan was no longer a serious threat to Oda’s ambitions.

Over the coming years, Tokugawa redeemed his humiliation at Mikatagahara and became one of Nobunaga’s most trusted advisors. We’re not going to go into every battle because we did that for our Oda Nobunaga bio, which is just sitting there, in case you’re interested. The short of it is that Oda had completely overthrown the shogunate and was on his way to uniting Japan when he was betrayed in 1582 and assassinated in what became known as the Honno-Ji Incident. With Oda Nobunaga gone, a new question arose – who would take his place?

Not the Right Time

There was a large power vacuum left by Oda’s death and, unsurprisingly, several people rushed to fill it, even though there was only room for one. A patient and cautious man, Tokugawa was not one of them. Even though Nobunaga had already designated his heir – his eldest son, Nobutada – he had died alongside his father at Honno-ji, so the warlord’s former daimyos were divided over who should take the reins. Tokugawa understood that things were about to get chaotic and violent, and that he would have to tread carefully if he wanted to keep his head, let alone remain in a position of power.

Ultimately, though, he had to make a choice, and he threw his support behind Oda Nobukatsu, Nobunaga’s eldest surviving son. However, it soon became evident that he had hitched his horse to the wrong wagon, as Toyotomi Hideyoshi, Nobunaga’s strongest general, was emerging as the odds-on favorite to claim the crown. On paper, Hideyoshi was supporting Nobunaga’s grandson, Hidenobu, to assume control of the Oda clan, but since the grandson was still in diapers, everyone understood that Hideyoshi would be the one calling the shots. And he had a lot of support, too, from other clans, but now that Tokugawa made his choice, he was stuck with it.

An inevitable conflict arose between the two sides, which met in battle several times during the Komaki Campaign in 1584. But neither group could score a decisive win, and each man recognized that eliminating the other one permanently would have been a costly and bloody endeavor that would leave him vulnerable to his enemies. Therefore, Hideyoshi and Tokugawa sat down at the negotiating table and reached a compromise: Tokugawa withdrew his support of Nobukatsu and formally agreed to become a vassal of Hideyoshi and, in exchange, he was given command of five provinces and left to his own devices.

Since Tokugawa was the last thorn in Hideyoshi’s side, his submission made it official that Toyotomi was now the man in charge. No more hiding behind Nobunaga’s progeny and pretending that the Oda clan was still running things. The Toyotomi clan had taken over.

Hideyoshi ruled for a decade-and-a-half, picking up where Nobunaga left off and continuing his conquest of Japan. If you want the full picture, check out the bio we did on him, but while all of this was going on, Tokugawa was busy in his little corner of the world. As we said, he was a patient man, and he knew that Toyotomi wouldn’t rule forever.

In 1590, the Hojo clan in the Kanto region of Japan was the last major holdout yet to submit to Hideyoshi so he invaded and, for the first time, requested Tokugawa’s help. The two of them made short work of their enemies and, as a reward, Hideyoshi granted Tokugawa the eight provinces they had just conquered from the Hojo clan in exchange for the five he already controlled in central Japan. Now, eight is greater than five, so, on paper, this was indeed a reward since Tokugawa would gain a lot of new territories. However, he also had to relocate from an area where he was well-established to one where he had no traditional connections, which was also much further away from Toyotomi’s capital of Osaka. In reality, this move was probably a clever way for Hideyoshi to limit his vassal’s power without giving him any reason to complain. In the end, Tokugawa accepted, since refusing would have meant war with Hideyoshi again, and he chose as his new headquarters the small town of Edo, which would later become better known as Tokyo.

Most of what we said so far painted Hideyoshi as a shrewd and calculating strategist, but he completely chucked that image in the bin during the 1590s with two disastrous invasions of Korea. Wisely, Tokugawa managed to stay away from that hot mess completely and spent those years consolidating his power in his new region.

In 1598, Toyotomi fell ill and established the Council of Five Elders who were supposed to rule as regents until his young son, Hideyori, came of age. He died soon after and Tokugawa decided that he had waited long enough. It had been 38 years since he first pledged himself to Oda Nobunaga. Now, he was older and wiser, he controlled the best-organized territory and commanded the strongest army in Japan. It was finally his time.

The New Shogun

The other four elders proved more loyal to Toyotomi, so in order for Tokugawa to assume power, he had to take them all out. Conveniently, one of them died of natural causes less than a year later, so one down and three to go. Weirdly enough, even though the other elders all rallied their armies against Tokugawa, his biggest threat was a fourth daimyo named Ishida Mitsunari. Even though Toyotomi didn’t see fit to include him in his little council, Mitsunari was a skilled commander who was the one to actually lead boots on the ground against Tokugawa.

This conflict wasn’t some drawn-out affair that went on for years and years. Quite the opposite in fact. The result was pretty much decided in a single battle that only lasted for a few hours. On October 21, 1600, a little village called Sekigahara in central Honshu bore witness to one of the most defining battles in Japanese history as both sides gathered the bulk of their armies and just went to town on each other. It was a resounding victory for Tokugawa, as a large portion of the enemy forces defected to his side after he promised them leniency, as well as generous rewards should he become the new leader of Japan.

And that was exactly what happened. Mitsunari and several other prominent daimyos who were loyal to Toyotomi were captured and executed days later. As for the remaining elders, two of them surrendered to Tokugawa following the loss at Sekigahara. They were spared their lives and even allowed to continue serving as daimyos, although their holdings were substantially reduced. The third went into hiding and he managed to elude Tokugawa for a few years. He, too, was spared the death penalty when he was found, and instead was simply exiled.

With nobody left to offer any resistance to Tokugawa, he took the opportunity to completely overhaul the power structure of Japan. He was sitting at the top, of course, and he radically redistributed the land the way he saw fit. Some loyal clans gained a lot of territory and influence overnight. Others were neutered by losing most of their land, while some clans, which Tokugawa considered implacable, were wiped out completely. The Toyotomi clan was allowed to stick around for now, and even permitted to remain at Osaka Castle, but with greatly reduced territory.

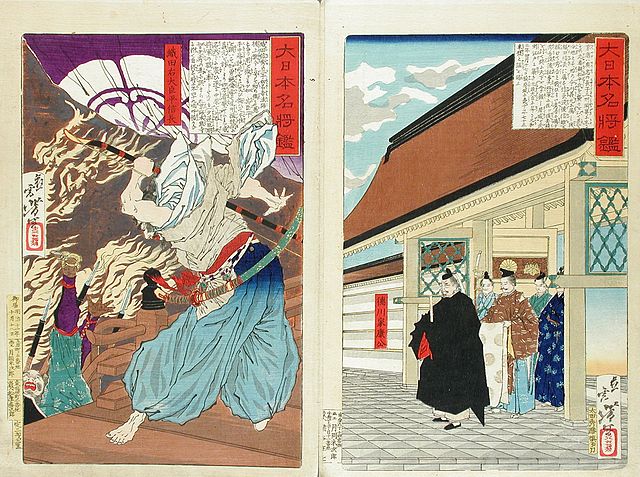

Everyone was at Tokugawa’s mercy so, in 1603, he decided to make it official. He went to the emperor and had himself appointed as the new Shogun of Japan, triggering the start of the Tokugawa Shogunate, the military government that would rule the country for the next 265 years until the emergence of Imperial Japan in modern times.

He had finished the job that Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi had started, which is why the three of them are known as Japan’s “Great Unifiers,” even though it wasn’t exactly what you would call a team effort.

But Tokugawa was 60 years old by the time he had finally assumed control and being shogun was a young man’s game. That’s why he retired just two years later and named his son, Hidetada, as the new shogun. But don’t be fooled. Tokugawa’s word was still the law, regardless of his title. The reason he did this was to ensure a smooth transition of power while he was still alive and avoid the mistakes made by Oda and Toyotomi.

Speaking of Toyotomi, the clan was now led by Hideyoshi’s original heir, his son Hideyori. Although at first Tokugawa spared him, he had second thoughts as the boy grew up into a young man who still commanded the loyalty of some daimyos who considered him the rightful ruler. Tokugawa decided to put a definitive end to such silly notions and laid siege to Osaka Castle in 1615, killing Hideyori and his family. Afterward, the shogun dissolved the Toyotomi clan, showing everyone else that he was absolutely ruthless when it came to any threats to his authority.

One of Tokugawa’s biggest efforts as shogun was to oversee major construction projects at Edo, transforming the settlement from a village into a burgeoning metropolis that serves as the heart of Japan even today. Hence why the Tokugawa Shogunate is also commonly referred to as the Edo Period.

Tokugawa’s feelings towards foreigners changed with the years. At first, he was happy with the trade they brought in, especially those fancy arquebuses and other firearms that proved invaluable in his quest to become shogun. But he had a change of heart towards the end of his life. He became particularly wary of all the Christians who came to his country to proselytize, so he put a sudden halt to their efforts by expelling all Catholic missionaries from Japan in 1614. From then on, he placed his country on a path of isolationism that Japan maintained for centuries.

With his rule firmly secure and his clan at the head of the entire country, Tokugawa Ieyasu considered his mission finally accomplished. He died on June 1, 1616, aged 73, and was deified as Tōshō Daigongen or “Great Deity of the East Shining Light”.