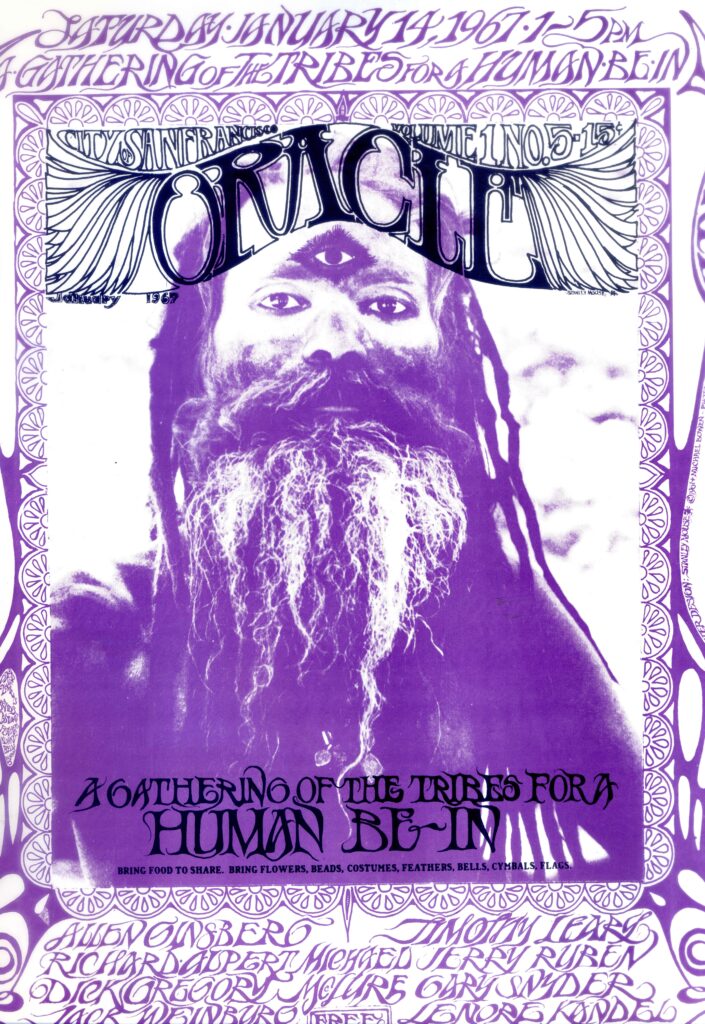

He was the person Richard Nixon once called the “most dangerous man in America,” a symbol of the counterculture who encouraged the country to “Turn on! Tune In! Drop Out!”

Trippy stuff, for sure, and that’s how Timothy Leary is largely remembered. While he definitely was a proponent of noshing on shrooms and tripping on psychedelic drugs, Leary was unique in that he gave a bit of professional creedence to the idea that opening your mind with LSD was a perfectly acceptable way of life and self-exploration… at least, he did at first.

Often cited as a Harvard professor — even though he wasn’t — Leary is a figure almost as surreal as the drugged-out trips he and his devotees endured throughout the 1960s and 1970s. He was so much more than a psychiatrist-turned-hippie-icon, leading a life filled to the brim with experiments well outside the norm of mainstream academia, in addition to the establishment of a controversial community and an escape from prison. Eventually, Leary claimed that his frequent use of hallucinogenic drugs gave him the ability to — among other things — commune with his ancestral past.

Enemy of the state or harmless hippie? You decide.

Getting in shape for the psychedelic revolution

Leary was born on October 22, 1920, and it was a simple case of perfect timing. He took a rather indirect route through school to graduate from the University of Alabama in 1943. Seven years later, he earned his doctorate in psychology from the University of California-Berkeley, which set him up nicely to have an established career by the time the counterculture movement of the 1960s was kicking off in earnest.

Before Leary ever became a figurehead for the drug culture of the 60s, he was shaped by the circumstances of his childhood and young adult life. A member of the so-called Greatest Generation — defined by growing up during the Depression and being sent to the front lines of World War 2 — Leary managed to dodge both of the traumas that shaped the rest of his generation.

His father was a dentist until, driven by alcoholism, he abandoned his family in 1934 for life as a merchant marine. Leary’s mother was fiercely devoted to him, and he was a handful. His education was a journey that criss-crossed schools; in 1938, he enrolled in the College of the Holy Cross, which is where he got an education of a different kind — he learned enough about life and religion to push him into giving up Catholicism. His second semester there became less about learning and more about hitting the bars, picking up girls in his newly purchased car, and running poker games.

After a year under the steeple, Leary set his sights on West Point. Withdrawing from Holy Cross after passing his West Point entrance exam, it wasn’t long until he was court marshalled for lying. The whole thing was hushed up so as not to bring dishonor to the school, but Leary was ostracized by his classmates and ultimately resigned.

From there, it was on to the University of Alabama, where he was expelled after being caught spending the night in the women’s dorm. He ended up at the University of Illinois, and was — as unlikely as it sounds — drafted into the Army. The details of his time as an enlisted man are a little sketchy, but we do know he spent some time working at a rehabilitation clinic in Pennsylvania, and was, perhaps unsurprisingly, suspended. He continued his training, though, marrying Marianne Busch in 1944 and talking his way back into the University of Alabama with the understanding that he would finish his degree via correspondence courses. He did.

From there, he worked his way through a Washington State University master’s degree, and a Berkeley doctorate. By this time, it was the 1950s, and an important shift was happening in the field of psychology.

Psychoanalysis was huge, driven by the need to find a reason why people were suffering from various mental illnesses, from depression to antisocial behavior. This was the post-war boom, after all, and America was riding high on a wave of victory and prosperity. But if Americans had served an instrumental role in defending the world from the most terrible threat to liberty that anyone had ever seen, then why were so many people unhappy?

This was the question that many mid-century psychologists were eager to solve. Many began preaching that the answer was all in a person’s head. It was taught that they were faulty, that there must be something wrong with them, that they were the ones failing to adapt to a changing world. By the middle of the 1950s, half of the country’s hospital beds were occupied by patients who had a diagnosis of mental illness.

This was the field that Leary entered. At first, he subscribed to all the typical ideas of the day. Psychology was about normalization, about “curing” someone by getting them to fit in better with what was viewed as normal society. But even then, there were dissenting opinions that decried this idea as a sort of coercion, rather than treatment, and some of the details of Leary’s personal life helped guide his shift away from the mainstream.

It was a rough decade for Leary. In 1955, his first wife committed suicide. She took her life on Leary’s 35th birthday, not long after confronting him about an affair — to which he reportedly told her, “That’s your problem.” Leary ended up marrying his mistress, but that marriage soon ended after the police were called by a landlady who heard him hit her. He reconnected with his estranged father, but that reunion was followed closely by his father’s death in 1956. Then, when a former male colleague was arrested after looking for illicit liaisons in public men’s rooms, Leary suffered a nervous breakdown. An extreme reaction? Perhaps — it was speculated that he and his married colleague had been involved in an affair of their own.

Leary needed to get out of town for a while to escape all the depressing elements in his life, so he headed to Europe. It was there that he met David McClelland. McClelland, who worked as the director at Harvard’s Center for Personality Research, became Leary’s new career opportunity. Just as important was his summer trip to Mexico, where he tried mushrooms for the first time. The result of these two coinciding events was the Harvard Psychedelic Project — a radical experiment fully sanctioned by the University executives.

Shrooms for science

Now, it’s important to note that Leary wasn’t the only academic interested in the effects — and possibilities — found in LSD. From 1953 to 1973, there were a series of psychedelic programs and studies run by various organizations across the United States. In fact, it’s estimated that the US government spent somewhere around $4 million dollars funding 116 studies that would look very similar to Leary’s most notorious experiments. Some studies were completely respectable, too, looking at whether or not LSD and mushrooms — both of which were perfectly legal at the time — could be used to manage things like depression, schizophrenia, and the pain of terminal cancer patients. Somewhere around 1,700 subjects participated, and those are just in the studies that have been made public.

Plenty of others weren’t public or as laudable, including the CIA’s attempts at using LSD as a truth serum during interrogations.

And this is important. When Leary got into the field, there was nothing illicit or controversial about it. Actor Cary Grant had a psychiatrist who treated him with LSD to great success, and author Ken Kesey credited his time as an LSD test subject for pushing him to write One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest. Leary simply tried it, liked it, and wanted in.

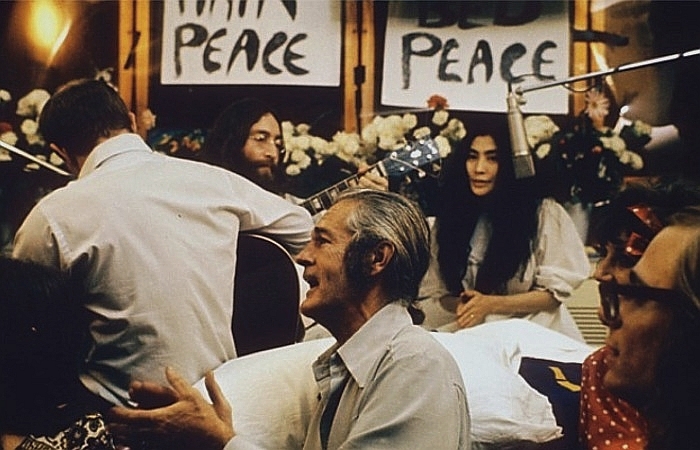

Leary had noble aspirations for his work. Not long after he first tried mushrooms, he read Aldous Huxley’s The Doors of Perception, which was written under the influence of mescaline. Huxley was conveniently lecturing at MIT, and when the two met over lunch at the Harvard Faculty Club, they came up with the idea that research into psychedelics would eventually lead to a kinder, gentler world filled with peace, prosperity, and an increased sense of contentment.

While that might not sound like a bad idea at all, it quickly proved to be, well, a very bad idea. The problem with studying subjects on LSD is that they’re absolutely out of their minds, and it’s very difficult to conduct thoroughly scientific research on subjects tripping out of their minds. So, Leary’s experiments were less than scientific.

Take the Concord Prison Experiment. That ran from 1961 and 1963, and involved administering psychotherapy to 32 prisoners in an attempt to see if treatment with hallucinogens would reduce prisoner recidivism. The idea was that using psilocybin — the active ingredient in shrooms — would allow subjects to have an experience that would teach them something about themselves or the world that they wouldn’t have learned with more mainstream therapies. It was suggested this could lead to a more successful integration into society.

Sessions were held in bi-weekly groups, with four subjects and two researchers, and after a series of prep sessions and evaluations, drugs were administered for a day-long trip. The group would discuss the experience, and subjects would be reassessed. According to Leary, the results showed promise. After the majority of the subjects were released, Leary initially reported that recidivism was well below the average, expected percentage.

Then, in a 1964 follow-up, Leary found that recidivism in his experimental group had regressed to the norm — in part, he said, because his team hadn’t actually provided the post-release support they had been planning. Still, Leary found something to lean on: the subjects that found themselves back in jail were there because of less serious offenses than they had originally been convicted of. He chalked that up to a win.

At the same time he was working with prison inmates, there were plenty of other less-than-scientific experiments going on under the guise of the Harvard Psychedelic Project. They were even less formalized, with many of the researchers simply opting to conduct experiments on themselves. In other words, they dropped a lot of acid.

Harvard wasn’t happy with the way things were going, especially when news about rampant drug use broke in the press. It went all the way to the FDA, who decided it was about time to start regulating just how these drugs were used. Leary’s program was shut down, and his term as a lecturer wasn’t renewed at the end of the 1963 school year. While he was preparing for his departure, one of his colleagues — an assistant professor named Richard Alpert — had a break with Harvard that was more dramatic. The media picked up the story that Alpert was fired when he was found trading LSD for sexual favors from undergrads. The mainstream press painted both Alpert and Leary as too much for Harvard to handle, and that’s not the kind of publicity that makes anyone look good.

Leary, on the other hand, didn’t actually leave Harvard because of the rampant drug use. Officially speaking, the college declined to invite him back because he’d abandoned his class. Instead of teaching he’d had his secretary give his students a list of required reading while he headed off to California.

Bringing LSD into the Mainstream

Leary and Alpert drifted a bit after leaving Harvard, heading to Mexico for a short-lived attempt at promoting LSD as a way of magnifying religious experiences. The Mexican government didn’t appreciate it, and had them shipped back to the States. Fortunately for Leary, he had come to the attention of a rich stockbroker named Billy Hitchcock, who just happened to own the 2,500-acre Hitchcock estate a few hours outside of New York City in Millbrook. At the behest of his sister Peggy — who also happened to be a former lover of Leary — he extended an invitation, and Millbrook became the center of Leary’s work and 1960s drug culture.

In spite of assuring the locals their days of experimenting with drugs were over, it was soon made painfully clear that wasn’t the case. Why painfully? Because any doubts about whether or not there was some serious drug use going on there were extinguished when Alpert — high and convinced he could fly — jumped out of a second-story window and broke his leg.

That particular incident came after another that illustrates just how crazy things got. When a vial of liquid acid had broken in Alpert’s suitcase on their way back from Mexico, well, that’s valuable stuff, indeed. Not about to let that go to waste, Alpert passed his clothes around to let people lick off a high.

The shenanigans that residents and visitors got up to at Millbrook exist somewhere between truth and legend, but there was a goal. Leary and Alpert were trying to find a way to create a road map for an LSD trip. They wanted to find that place of perfect clarity and understanding, and develop a way for practitioners to get to that point on a regular basis. In the beginning, they held workshops, gave lectures, and wrote almost as much as they tripped, but it didn’t take long for the FBI to come knocking.

On April 17, 1966, officers found 12 children and 29 adults, but none of the drugs they were looking for — only a bit of marijuana. Still, roadblocks were set up, and anyone who wanted to go into their free-wheeling compound was strip searched by law enforcement. Another dream was dead.

Reading it for the articles

In 1966, Playboy ran an interview with the rogue psychiatrist where they talked about what he’d learned from taking LSD 25 — a substance touted as 100 times stronger than the shrooms he’d first eaten six years prior. At the time, he said he had undergone 311 “psychedelic sessions”, and he went on to talk about how the sessions had revitalized him — adding that he believed a 15-year-old would be precisely the right age to make the most of an LSD experience.

It wasn’t the only iffy proclamation he made, either. The so-called “psychedelic dropouts” — those who checked out of mainstream society to spend much of their time tripping — shouldn’t be considered a problem, he said. Instead, they should be lauded for their devotion to discovering ancient wisdom. He described mainstream society as “an air-conditioned anthill,” and likened his LSD activists to history’s greatest thinkers.

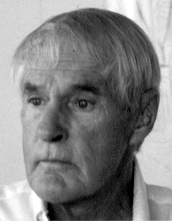

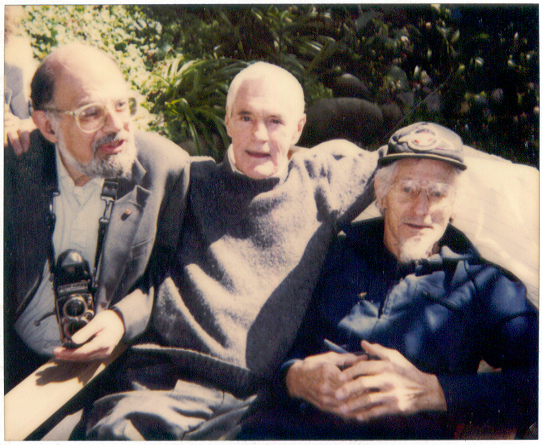

Credit: commons, CC BY-SA 3.0

To be fair, Leary also called for special legislation to be put in place around the use of LSD. Why? Because a bad trip could go horribly wrong, and it took experience to guide someone through the drug-induced haze. In order to guide someone, he believed, a person should have to apply for a license — which they would only get after study, preparation, and passing a series of physical and psychological tests. He argued this was much more responsible than doing something like outlawing it altogether. Without a legitimate way of getting and using this substance — one he defined as a form of energy, rather than a narcotic or a type of medicine — he thought the industry would become lawless and underground, much like what happened to alcohol in the years during Prohibition.

He also made some wild claims about what he’d discovered on his hundreds of trips, telling them he had managed to move his consciousness into the pre-cellular level. What exactly is that? He described it as becoming one with the cosmic beat of the universe, and he even claimed to be able to tap into his own DNA to relive the experiences his ancestors had generations ago. He described particular people he saw again and again, scenes of chaos and crisis, all laid bare by so-called “ancient energies”.

When asked about the most important lesson he’d learned on his trips, he gave an insightful answer. He said, “[The] only real issue, when you come down to it, in the evolutionary cosmic sense: whether to make it with a member of the opposite sex and keep it going — or not to.” Everyone had to make a choice: to have children and attain immortality or, as he put it, “step off the wheel.”

And that’s a big part of why we remember Leary today, and why he made such a sweeping impact on the culture of his time. While experimentation before him focused on making LSD a psychological weapon, Leary argued that it could lead to vast insights not only into the self, but into the cosmos and into parts of the world larger than any human could ever imagine… unaided, of course.

The long arm of the law

It’s not surprising that law enforcement had Leary on their radar. He’d already been arrested on federal drug charges in 1965, and was handed a 30-year sentence, but was still allowed to go free on appeal. He was arrested again after the raid at Millbrook, then again in 1968. It was that arrest that got Leary’s wife, Rosemary, a 6-month sentence while Leary was transferred to the California Men’s Colony Prison. And this is where the tale takes a turn worthy of one of his LSD sessions.

Leary managed to escape from prison with the help of a militant activist group called the Weathermen. The Weathermen — who became the Weather Underground when they went into hiding — started out as part of the campus-run Students for a Democratic Society. Their peaceful protests against the Vietnam War were getting little in the way of results, and some members splintered into the Weathermen and turned more violent. In October of 1969, they kicked off the “Days of Rage” by marching through a Chicago shopping district armed with lead pipes and a lot of anger. They later bombed the headquarters of the National Guard and had plans to bomb other high-profile targets around the country, and in the meantime, they gave Leary a way out of jail.

Leary and his wife were smuggled out of the US and into Algiers, where they stayed with the minister of defense for the Black Panthers, Eldridge Cleaver. Cleaver and Leary didn’t see eye-to-eye on things, particularly Leary’s continued drug use. It was, after all, an Islamic country with a tendency to go hard on drug offenses, so Cleaver essentially pushed Leary and Rosemary out of town. From there, it was on to Switzerland, where they hooked up with arms dealer Michel Hauchard. They made an agreement: Hauchard would protect them, as long as he was given 30 percent of the royalties from the books Leary planned to write.

And here’s why you should never get involved with high-profile arms dealers. Hauchard knew that the more books Leary wrote, the more money he’d get, and decided his cash cow would be more productive in a place where he had no distractions. And that was jail. Hauchard turned him in, and he spent a month in solitary confinement before Rosemary was able to get him released.

After that, Rosemary left him. It’s not long before he found someone new in Joanna Harcourt-Smith Tamabacopoulos D’Amecourt, and he found something else — heroin. From there, Leary and his new lady departed for Austria, where he lauded the country as “a beacon of compassion and freedom.” They weren’t nearly as fond of him as he was of them.

In January 1973, Leary’s son-in-law was in town, and they decided to head out and meet up with the hashish suppliers of Afghanistan. Unfortunately for Leary, it was all a set-up. He was handed over to law enforcement, returned to Los Angeles, and dropped into a Folsom Prison cell — which, interestingly, made him Charles Manson’s new neighbor.

Oh, to be a fly on the wall for those conversations.

Timothy Leary: informant, spaceman, game designer

Leary never quite adopted a totally clean and entirely wholesome life, but he did begin cooperating with authorities. He informed on old colleagues and his ex-wife Rosemary, who had seemingly dropped off the face of the earth after leaving him in Europe. He did some jail time, but was free and in Witness Protection by 1976. That didn’t last long — he was soon hanging out at the Playboy Mansion and contributing to Hustler.

He also found a new philosophy, one that looked less to the past and more to the future. While he was in prison, he came up with a new theory: SMI2LE, which stands for Space Migration, Increased Intelligence, Life Extension. Essentially, Leary outlined what he believed was the next necessary step for mankind; as our ancient ancestors once evolved to walk on land, Leary believed we needed to evolve to travel the stars. Without expanding our physical horizons, he thought, it was pointless to expand our mental ones.

Credit: Tex Brook – Flickr: Max Parrish as Eli / Bud / Fritz and Timothy Leary as Mr. Jones, CC BY 2.0

It wasn’t the only late-20th century technological advancement he was interested in, either. He also tried his hand at developing video games, including one called Mind Mirror and another, sadly unfinished game called Neuromancer: Mind Movie. That foray into technology and gaming wasn’t short-lived, either, and by the ’90s he had declared that “the PC is the LSD of the 1990s”. HIs new philosophy was “turn on, boot up, jack in,” and, strangely, widespread use of technology, computers, and games took off in much the same way Leary had once hoped LSD would.

In 1995, Leary was diagnosed with inoperable prostate cancer. Initially, he insisted that he wanted to meet death on his own terms, and claimed he had plans to commit suicide and broadcast the act live on the Internet. Instead, he passed peacefully in his sleep. according to friends and family that were with him, and his last words were, “Why? Why not.”

Leary was cremated, and his ashes have had a journey just as bizarre as the one he took through life. Part of his remains were given to actress Susan Sarandon, who has since talked about how she and a group of friends had taken the ashes to the Burning Man festival, where they added some to their beverages and drank him in a toast. Another 7 grams of his ashes were blasted into space in a cylinder that contained the remains of several others, including Star Trek creator Gene Rodenberry.

Leary may not have seen the rest of the world take on the final frontier, but it’s fitting that he did.