At first glance, it seemed like Thutmose III was destined to become a footnote in history, just another name on a long list of kings who once ruled over Egypt. His father had been a mediocre ruler, dying when Thutmose was only three years old. Afterwards, his stepmother took power for herself and it would not have surprised anyone if the young pharaoh simply vanished without explanation.

But that did not happen. In fact, as a young man, Thutmose learned and trained in the ways of warfare, anticipating that one day he would assume the throne. And that he did, and he immediately embarked on one military campaign after another, always looking to increase the size and power of his empire.

He only stopped when it became clear that Egypt was the single most powerful nation in the region, and his empire was the largest in the world.

Rise to Power

Thutmose III was born circa 1481 BC, and was part of the 18th Dynasty of Egypt, the first one of the New Kingdom. He was the son of Pharaoh Thutmose II, and a secondary wife named Iset.

His name is alternatively spelled as Tuthmosis or Thothmes although these all appear to be Greek variants of his actual Egyptian name which was Djehutimes. But, of course, as we learned in the bio on Tutankhamun, a pharaoh did not have a single name. No, in fact, his royal titulary contained five names, and each one possessed variations found on different inscriptions.

And now, for your entertainment, I am going to attempt to pronounce all of them. The royal titulary of Thutmose III was Ka nakht kha em Waset/ Wah nesyt mi Ra em pet/ Djoser khau sekhem pehty/ Men kheper Ra/ Djehutimes nefer kheperu. Roughly translated, it meant “The strong bull arising in Thebes/ Enduring of kingship like Ra in heaven/ Sacred of appearances and powerful of might/ Lasting is the Manifestation of Ra/ Thoth is born, beautiful of forms.” So this video won’t be one hour long, we are going to simply stick with Thutmose.

Normally, the heir to the throne was the son of the pharaoh with his Great Royal Wife who, in this case, was Hatshepsut. However, the two of them only had one daughter, Princess Neferure, whose ultimate fate remains a mystery. Therefore, the throne went by default to Thutmose III as he was his father’s only son.

Speaking of Hatshepsut, we already did a full video on her where we talked about the complicated and uncertain relationship which she had with her stepson, so we are not going to rehash all that information here again. To give you the cliff notes version, Thutmose II died when his son was only 3 or 4 years old. He was too young to take over the throne so, instead, Hatshepsut served as his regent. However, after a few years, she managed to assume full power, becoming one of the few and, arguably, the most successful example of a female pharaoh.

The exact circumstances under which Hatshepsut took power from Thutmose III are still a mystery. When this event was first discovered about a hundred years ago, scholars of that time branded Hatshepsut a manipulator and a usurper. After all, following the female pharaoh’s death, someone tried to erase her from history and the most likely suspect would have been her stepson. The main reason why he would have done this would have been if he harbored deep resentment towards his stepmother, right?

Well, many modern historians aren’t completely sold on this idea anymore, mainly because there is no solid evidence to back it up. There are no ancient documents or inscriptions to suggest that Thutmose ever tried to rise up and take back power from Hatshepsut. Since he obviously outlived her, Thutmose would have had ample time to record his victory in the history books, mentioning how he won back his empire from his evil, manipulating stepmother. The pharaohs recorded all their triumphs on obelisks, stelae, and tomb inscriptions. The fact that no such proclamation exists (or, at least, has not been found yet) suggests that maybe the relationship between Hatshepsut and Thutmose III was more amicable than scholars initially believed.

Add to this the fact that Hatshepsut’s attempted erasure from history likely occurred decades after her death, so a more probably culprit would have been Thutmose’s own son, Amenhotep II, who may have done it to try and claim some of Hatshepsut’s accomplishments as his own.

Lastly, perhaps the most telling indicator that Thutmose felt no ill will towards Hatshepsut was the fact that he ultimately became a pharaoh. Rule one of the “Usurper’s handbook” is that you do not allow the person you have usurped to live. You can look at other examples in history and that person always met with an unfortunate “accident” or simply disappeared from the historical record.

What little evidence we have of Thutmose’s early years suggests that he lived a relatively happy and safe life under Hatshepsut, having been granted an extensive education in anticipation of him one day ruling Egypt. He was not even kept under tight supervision, as the young heir lived more with the soldiers than he did at Hatshepsut’s court, learning all the intricacies of warfare, plus skills such as hand-to-hand combat, horse riding, and archery. To show her complete trust, towards the end of her reign, Hatshepsut even placed Thutmose in charge of her armies, though she had little interest in conquest and mainly used them to secure the borders and protect trade expeditions. She seemingly did everything she could to ensure that, when she finally died, her empire would be left in good, strong, capable hands.

The Battle of Megiddo

So Hatshepsut died in 1458 BC, going by the conventional Egyptian chronology, and Thutmose III finally came to rule over his empire, 22 years after he actually became a pharaoh. He took a decisively different approach to governing than his stepmother, mobilizing Egypt’s armies and becoming a mighty conqueror. Of course, he had the benefit of decades of peace of prosperity which allowed the empire to flourish and get richer. Thutmose would go on to become ancient Egypt’s most formidable military leader, expanding the empire to its greatest ever territorial extent. Ancient records show seventeen major military campaigns into foreign lands starting with Thutmose’s first year as sole ruler, and this does not take into account minor skirmishes or battles to defend the borders.

While we are not going to discuss all of the campaigns, we will examine the most important ones and we start off with the first. It was against the city of Megiddo, situated in modern day Israel. It would later become a place of biblical significance because it was mentioned in the Book of Revelations 16:16 as the location of a great battle that would mark the end times. However, the city became much better known by its Greek name of Armageddon.

In the 15th century BC, though, Megiddo was part of a group of Canaanite cities which were under the hegemony of the pharaoh. They were not part of Egypt but, while Hatshepsut reigned, they paid tribute and sent over soldiers for her armies. However, as is often the case when there is a period of transition of power, Megiddo considered the death of Hatshepsut and the ascension of Thutmose as the perfect time to rebel, hoping that the new pharaoh would be less formidable than his predecessor.

That turned out not to be the case. It is likely that either Thutmose or Hatshepsut saw this move coming. The pharaoh was quick to mobilize his army to march on Megiddo and, according to his personal military scribe Tjaneni, he covered 150 miles in ten days. Add another day’s rest and, in 11 days, the Egyptian army arrived in Yehem, today called Yavne’el, near the fortress city of Megiddo.

The Egyptians were not only facing the people of Megiddo as the city entered an alliance with another ancient Levantine kingdom named Kadesh. The King of Kadesh also convinced other Canaanite settlements to help their coalition, as well as the Kingdom of Mitanni. There were quite a few states in the area who were eager to see Egypt’s power and influence dwindle, and they thought that this was the perfect opportunity now that the nation was governed by someone young and inexperienced. They planned to do everything in their power to keep Thutmose’s reign short but, in the end, they would not get their wish.

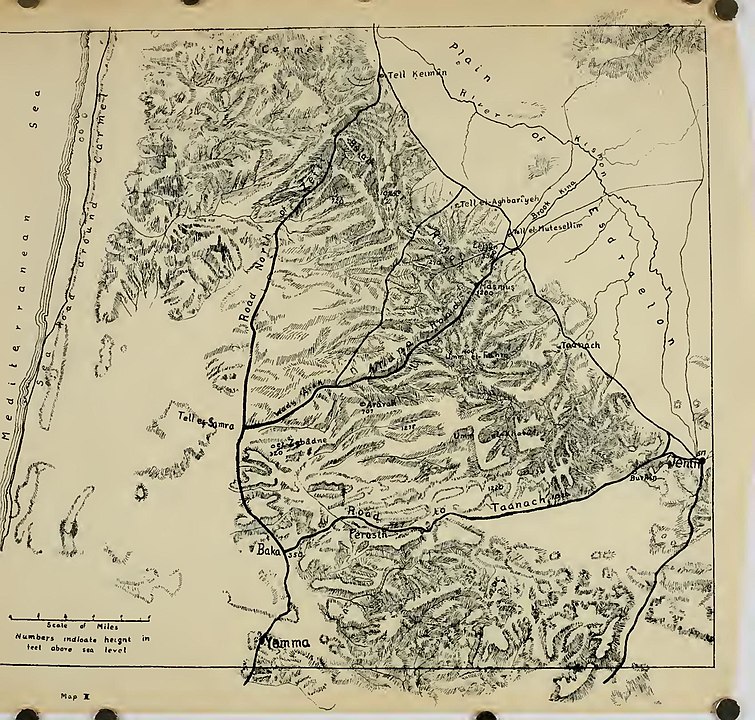

In Yehem, the pharaoh conferred with his most senior advisers because he had to make an important decision – he had to select the way by which he would approach Megiddo. He had a choice between three roads. Two of them were broad and in the open so traveling on them would be safe and fast. The third was a narrow pass where his soldiers would have to walk single file and would lead to his vanguard engaging the enemy in combat while the soldiers at the rear were still traversing the pass. As you might expect, all his advisers recommended that Thutmose choose one of the safer roads, but the young pharaoh said this to his generals:

“I swear, as Ra loves me, as my father Amun favors me, as my nostrils are rejuvenated with life and satisfaction, my majesty shall proceed upon this Aruna road! Let him of you who wishes go upon these roads of which you speak and let him of you who wishes come in the following of my majesty! ‘Behold’, they will say, these enemies whom Ra abominates, ‘has his majesty set out on another road because he has become afraid of us?’ – So they will speak.”

Unsurprisingly, after his speech, all his commanders agreed to follow their pharaoh. Thutmose then went outside and talked to his men about traversing the dangerous pass, promising them that he would be at the front of the column. So the entire Egyptian army traveled the perilous road, but this proved to be a stroke of genius. When they finally emerged on the other side of the pass, they found no enemies waiting for them. In fact, the coalition never considered that Thutmose would take this road so now the Egyptians had the element of surprise on their side.

The Battle of Megiddo most likely occurred on April 16, 1457 BC. The size of the armies can only be vaguely estimated, but historians believe each side had at least 10,000 men, probably closer to 15,000. We again have the words of Tjaneni the scribe to tell us how the battle went down:

“His majesty went forth in a chariot of electrum, arrayed in his weapons of war, like Horus, the Smiter, lord of power; like Montu of Thebes, while his father, Amon, strengthened his arms. The southern wing of this army of his majesty was on a hill south of the brook of Kina, the northern wing was at the northwest of Megiddo, while his majesty was in their center, with Amon as the protection of his members, the valor of his limbs. Then his majesty prevailed against them at the head of his army, and when they saw his majesty prevailing against them they fled headlong to Megiddo in fear, abandoning their horses and their chariots of gold and silver. The people hauled them up, pulling them by their clothing, into this city; the people of this city having closed it against them and lowered clothing to pull them up into this city. The fear of his majesty had entered their hearts, their arms were powerless, his serpent diadem was victorious among them.”

This account was clearly spruced up to make Thutmose seem as heroic as possible, but the scribe does mention a mistake on behalf of the pharaoh. Once the enemy had begun retreating, he did not press the attack immediately, instead allowing his men to plunder the battlefield. If he would have engaged the fleeing combatants, he could have ended the war right then and there. Instead, the soldiers retreated inside Megiddo, which was a fortress, and Thutmose had to lay siege on the city.

The King of Kadesh had managed to make his escape. Meanwhile, the Egyptians had no other choice but to wait until the people of Megiddo ran out of supplies and surrendered. It took seven or eight months before they finally exhausted all their food and water and had to throw themselves at the mercy of the pharaoh.

And, indeed, Thutmose was pretty merciful, by their standards, anyway. Of course, he plundered Megiddo of its valuables, taking tens of thousands of cattle, over 2,000 horses, almost 1,000 chariots, countless weapons, laborers, and suits of armor. But he did not burn the city, he did not kill its population, and he did not even execute the high officials responsible for the insurrection. He did replace them with people loyal to him, and he also took their children to be raised back in Egypt although, in reality, they were taken to act as prisoners in case their fathers got any more ideas of rebelling.

The Campaigns Continue

This was far more than a victory against one city. Besides the fact that Thutmose now held a location with important strategic value, his triumph at Megiddo instantly made him known as a force to be reckoned with in the region.

Even so, Thutmose knew that his hold on Canaan was tenuous, at best. The numerous other cities in the area might have not openly raised arms against him, but they were certainly no friends of Egypt. If he were to simply return home, it would not be long before they would renounce his authority, even openly rebel against him, especially if aided by other powerful factions like Mitanni or Kadesh.

Holding Megiddo, Thutmose did have an advantage. Besides its strategic value, the city was also a vital agricultural center which provided a lot of food for nearby cities. If the pharaoh were inclined to wait until winter, he could have simply starved them into submission. But he saw no need to delay. He still had a strong army and fresh supplies so he continued his military campaign.

It has been estimated that throughout Thutmose’s entire career, he conquered well over 300 cities, towns, and other various settlements. The others did not really benefit from a detailed account like that of the Battle of Megiddo, though, as most of them simply had itemized lists containing the spoils of war. Presumably, this is partly because most of those people chose not to fight at all, and simply submitted to the pharaoh.

Anyway, from Megiddo Thutmose traveled north, following the course of the Litani River. There were still some cities, like Tyre and Sidon, who were on friendly terms with the Egyptians, and they were glad to have them in the area, helping to minimize the influence of other nations, Kadesh, in particular. According to ancient records, Thutmose also built a fortress somewhere in this region, which was called “Menkeheperre-is-the-Binder-of-the-Barbarians.”

With the arrival of autumn, Thutmose decided that it was probably time to return to Egypt. Each new settlement he conquered meant another garrison which he had to leave behind to ensure peace so his army was starting to dwindle. On the other hand, he was returning to Thebes with over 7,000 captives. These were not strictly slaves, but rather unpaid workers, who were expected to pay part of their tribute in the form of free labor.

The following spring, Thutmose departed Egypt again with his army, but the next military campaigns mainly involved collecting tribute and only occasionally putting down a new rebellion, as a show of force was generally enough to keep most of the other cities in check.

Of course, this didn’t always work. Thutmose was faced with a crisis when the city-state of Tunip revolted, alongside Kadesh and their vassals, and also aided by the Mitanni who remained Egypt’s most powerful foe. The pharaoh had to react quickly and, this time, he was far more ruthless in his actions. Ancient records state that the settlements which rebelled were “destroyed.” The city-states of Tunip and Kadesh, however, were a bit more challenging.

In the end, Thutmose chose to attack Tunip. Kadesh was a veritable fortress and the only way to defeat it was with a long siege and the pharaoh did not have time for one when the entire region was close to insurrection. Tunip was the easier target and it ended up being even easier than Thutmose expected because neither Kadesh nor Mitanni came to its aid so the city had no choice but to surrender and accept whatever punishment the pharaoh had in store.

War with Mitanni

This made it pretty clear to Thutmose that he had to deal with the Kingdom of Mitanni one way or another. For this, however, the pharaoh needed to find a way of traveling around five hundred miles all the way from Egypt across the Euphrates River with an army while keeping it fed, healthy, and safe enough so that it would be able to fight a powerful foe at the end of the journey. This was a tough task 3,500 years ago, considering that a large army could only average around ten miles per day and that’s not taking into account minor skirmishes it would likely encounter along the way. To achieve his goal, Thutmose needed a place that he could reliably use as a forward base of operations and a faster method of transportation.

This was not something that the pharaoh achieved in one go. In fact, he fought the Mitanni for about half of his sole reign, engaging them in one way or another during, at least, nine military campaigns. He continued to build fortresses further up north into his empire. Starting with his sixth campaign, he began approaching Canaan by sea, which was faster and allowed him to submit the problematic city of Kadesh. As he slowly, but steadily built up his fleet, Thutmose also brought the Phoenician port cities under his control to gain access to their harbors.

Eventually, the pharaoh’s strength in that area grew large enough that he was able to cross the Euphrates River and launch a surprise invasion on his foe, capturing the major Mitannian city of Aleppo, located today in Syria. It was a huge blow for the Mitanni whose influence on the region decreased significantly. They weren’t wiped out completely, but it became clear who was the major power in the region. As an added bonus, the nearby kings of the Hittites, Babylonians, and Assyrians all gave gifts to Thutmose as tribute to show their submission. It was, arguably, Thutmose’s most notable military campaign and, when he returned to Egypt, he commemorated his triumph by erecting a large obelisk which can still be found today, except that it’s in Istanbul, having been moved by Roman Emperor Theodosius.

Speaking of the obelisk, we mainly focused on Thutmose’s military career, since that is what he is primarily remembered for, but we should mention that he was also a prolific builder who commissioned over 50 monuments, temples, and tombs during his reign. If nothing else, Thutmose needed all those extra walls and columns so he would have the space to record all his military victories.

The place that benefited most from his attention was the vast temple complex located today near the modern city of Luxor, best known simply as Karnak. Thutmose did not found it, but he added more constructions to it than any other pharaoh, mainly to the Temple of Amun. Even today, Karnak is famed for its giant pillars and is one of the main reasons why Luxor is dubbed the “world’s greatest open-air museum.”

Mummy Dearest

Like with other pharaohs, we like to complete Thutmose’s story by looking at what happened to him after he was turned into a mummy. Thutmose III died in 1425 BC, aged 56 years old, under unknown circumstances. His son, Amenhotep II, became the new pharaoh, while Thutmose was buried in Tomb KV34 in the Valley of the Kings. His burial location is part of the Royal Cache which is a complex of tombs that contained many pharaohs, royal wives, princes, princesses, and high priests from the 17th up to the 21st dynasties.

Unsurprisingly, Thutmose wanted to be buried there because it was the final resting place of his father, grandfather, and ancestors. The downside was that this was a very well-known area and the tombs were subjected to heavy looting and desecration. When Thutmose’s mummy was first unwrapped in modern times during the late 19th century, French Egyptologist Gaston Maspero noted that his mummy had been “torn out of the coffin by robbers, who stripped it and rifled it of the jewels with which it was covered, injuring it in their haste to carry away the spoil. It was subsequently re-interred, and has remained undisturbed until the present day.”

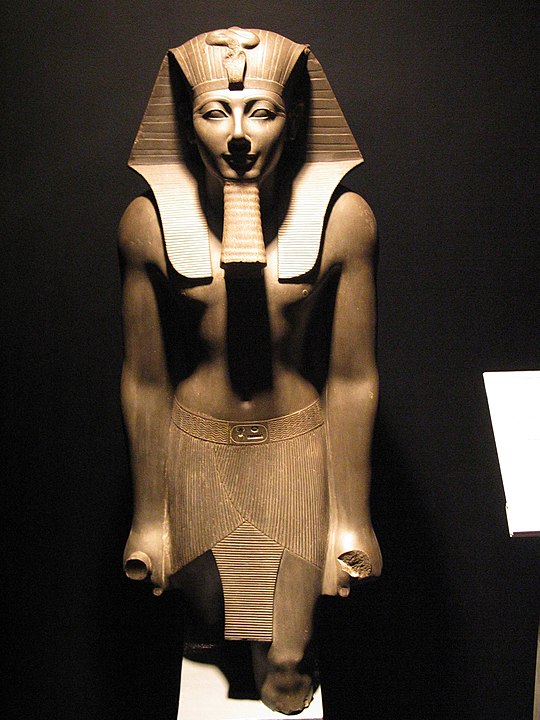

His mummy had suffered extensive damage. In fact, it was among the worst conditions for any mummy recovered from the Royal Cache. This wasn’t helped by the fact that it was removed, unwrapped, and examined using 19th century technology which probably made things worse. Only his head was intact, and remains intact at the Cairo Museum, but scholars still noted that it did not show the image of manly beauty with intelligent features depicted in his statues, but rather someone whose forehead was “abnormally low, the eyes deeply sunk, the jaw heavy, the lips thick, and the cheek-bones extremely prominent.”

But, of course, none of this mattered. At the end of the day, Thutmose made Egypt a dominant power once more, and forged the largest empire in the world, a record he kept for almost 800 years.