History is a delicate endeavor. It tends to remember those who make a lasting impact as larger-than-life figures, defined by their contributions, as well as the effects that ripple and unfold after the fact. It’s easy to forget that many of the people who shaped our world started out just like everyone else. They had to obey their parents, for better or worse. They played — and argued — with their siblings. They got into trouble in school. They struggled to find a direction in life.

The Wright brothers were two such ordinary figures. They weren’t born into wealth or power; they didn’t have clear goals in life for a long time; they didn’t even graduate from high school, because of circumstances beyond their control. But after their first flight on December 17, 1903, they set in motion a series of events and advancements that had a profound effect on the world.

At first, no one believed the Wright Brothers had developed an aircraft powered by an engine and controlled by human drivers… yet just 38 years later, the Avro Lancaster — the plane that would become one of the Allies’ most successful weapons during World War II — rolled off the assembly line.

Before flight became a revolutionary development in travel, diplomacy, logistics, or warfare, it was the obsession of two brothers — fueled by curiosity, and powered by the influence, love, and encouragement of an entire family.

A Pair of Happy Childhoods

It was Wilbur Wright who once said, “If I were giving a young man advice as to how he might succeed in life, I would say to him, ‘Pick out a good father and mother, and begin life in Ohio.'”

To truly understand Wilbur and Orville Wright, we’re going to need to start with their parents, because in another environment, or in another family, governed by other parents, it’s entirely possible these two gentlemen would have been uninspired church janitors.

The patriarch of the Wright family was Milton, or as he was known to his brethren, Bishop Wright. Born in 1828, he grew up working on his parents’ Indiana farm, where he practiced his public speaking skills as he toiled away in the fields, reading every book he could find, and developing a firm belief in the evils of slavery. It was also in those fields that the 15-year-old Milton had something of a religious epiphany, one that he later explained like this:

“It was not by forces, visions, or signs, but by an impression that spoke to the soul powerfully and abidingly… There was no sudden revolution from great anguish to ecstatic joy, but a sweet peace and joy [which I had] never known before.”

It wasn’t until 1847 that he joined the Church of the United Brethren, rising quickly though the hierarchy in an organization that recognized his gift for giving sermons and relating to people in an unprecedented way. He was eventually made a circuit preacher, which means he traveled from church to church across the state. One of the towns on his circuit was Hartsville, where he not only visited the church, but also saw a woman he had courted in college. They had separated after he developed a serious illness, but he had never forgotten her. When the church reassigned Milton to the wild frontier and gold mining towns of Oregon, he asked her to marry him. She agreed that she would wait for him to return, and if they still felt the same, they would marry. Two years later, he returned to Indiana and married Susan Koerner.

Their first and second sons, Reuchlin and Lorin, came along in 1861 and 1862. It was another five years before Wilbur was born and, after the birth of twins who died in their infancy, Orville was welcomed into the family in 1871. Three years later, the family was completed with the arrival of a sister, Katharine. For their entire lives, the siblings — particularly Wilbur, Orville, and Katharine — remained incredibly close. It was Katharine who once described their childhood in terms that would make anyone envious, saying,

“No family ever had a happier childhood than ours. I was always in a hurry to get home after I had been away half a day.”

Changing the course of the world… one child at a time

The daily life of the Wright siblings was strict and disciplined, but it was also a warm, loving environment with parents who encouraged their children’s individual talents. In some ways, Milton was staunchly conservative, but he was also very progressive in his views on things like the abolition of slavery and other social issues. He did meet his wife while she was studying for a literature degree from Hartsville College, and in the mid-19th century, that wasn’t exactly normal for women.

Milton continued to travel with his church job and was away from the family for long periods, but he made sure to stay active in their lives; he sent them regular letters, gave them complete access to his extensive library, and brought them gifts… including one that sparked an interest in Wilbur and Orville that wouldn’t truly develop for many years.

They called it “the bat,” and it was a toy helicopter that Milton gave the boys in 1878. It was based on the design of a French aeronautical pioneer named Alphonse Penaud, and it was essentially a rubber band attached to a propeller that would send the toy shooting up into the sky. Wilbur and Orville — then 11 and 7 years old, respectively — attempted to make their own, larger versions of the toy, and while they never quite pulled it off successfully, it did kickstart a fascination with machinery. They never forgot this gift, either. Decades later, they would write about how that one simple toy, that one small gift from a loving father, eventually guided the course of their entire adult lives.

Their mother, too, had a huge impact on their love of all things mechanical. Susan Wright had grown up working alongside her father in his carriage shop, where she, too, nurtured a lifelong love of machines and gadgets. Wilbur and Orville grew up watching her design and build small appliances for use around the house; they also played with toys she had built for them. As adults, the brothers recognized the influences their parents had. Orville once said,

“We were lucky enough to grow up in an environment where there was always much encouragement to children to pursue intellectual interests; to investigate whatever aroused curiosity. In a different kind of environment, our curiosity might have been nipped long before it could have borne fruit.”

That’s not to say everything was easy. Because Milton’s position in the church involved so much travel, the whole family often found itself uprooted as well, moving alongside him as he established training schools for those interested in learning the church’s theology. At one point, Milton even helped found a seminary college.

But all was not well within the church, and in the years after Katharine’s birth, a schism developed between those who wanted the church to stay the same as it had always been, and the more liberal-minded folks who were looking to change the church’s stance on everything from social issues to secret societies. Milton was on the side of the conservatives, but he was in the minority. By 1881, he had been removed from his position as bishop and returned to the same Indiana circuits he had preached on when he first courted his wife. Yet even as a church drama played out on a national scale with him directly in the center, something far more dramatic was happening in the Wright household: Susan was diagnosed with tuberculosis.

By this time, the precocious boys who had been captivated by a flying toy were in high school. Orville was gravitating toward science and technology — he was known for being equal parts clever and mischievous, yet when he was around those he didn’t know, he was almost painfully shy. Like many brilliant students, he had trouble applying himself to a curriculum, so instead of going through his required, junior-year classes, he opted for college prep courses. Unfortunately, that disqualified him from getting a high school degree, so he decided he simply wasn’t going to bother with school anymore.

Wilbur didn’t graduate high school, either. The family moved again before he could finish. He eventually skipped the end of high school and went straight into college prep classes, with the hope of going to Yale and becoming a teacher, but fate had other things in mind. Where Orville was the shy one who loved practical jokes, Wilbur was confident, eloquent, and always level-headed… until the winter of 1885.

That unfortunate season saw Wilbur playing ice hockey with a group of friends when he was hit in the face by a rogue stick. He lost most of his upper teeth and was housebound for weeks. The untimely accident would only get worse — complications from the injury turned into digestive issues, heart palpitations, and long bouts of depression that made him abandon his hopes of Yale. Instead, he spent the next few years of his life caring for his already-ill mother, until her death in 1889.

Now, history is a strange thing, interconnected in ways that are nothing short of bizarre… so here’s where it’s worth taking an aside. The boy who hit Wilbur was named Oliver Crook Haugh, and while it’s unclear whether it was an accident or on purpose, we can say that he was known as a neighborhood bully. Haugh — who was working at a local drug store — later became addicted to one of the most typical medicines of the era: Cocaine Toothache Drops. The combination of drugs, alcohol and erratic behavior saw him committed to an asylum, and when he got out, he ended up reading Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. At first, he identified with Jekyll, believing his newly earned medical degree was going to help him in finding a great cure-all. But as his cocaine habit continued, he wrote that he was becoming more like Mr. Hyde.

Oliver’s true descent into darkness started six years after that 1885 incident on the ice; between 1891 and 1905, it’s believed he killed at least sixteen people — starting with his fiance’s father, and including his own mother, father, and brother. In 1907 — the same time Wilbur and Orville were trying to get people to take their inventions seriously — he was executed for his crimes.

Finding purpose in each other

The passing of a beloved parent spawns grief well beyond words, and everyone deals with that grief in their own way. Within days of burying Susan, Milton was back at work. Wilbur and Orville attacked work as well, embarking on a journey to start a publishing business and newspaper. Wilbur was to serve as the editor and Orville as the publisher. It was called the West Side News, and it wasn’t as much of a familial departure as you might expect — their father had been the editor of a publication called the Religious Telescope, and while they were still in school, they had printed their own newsletter called The Midget. While it had honorable beginnings — the idea was that they were going to advertise a fledgling printing business — their parents quickly put them out of business when they found out they intended to run a column called “The Inherent Wickedness of Schoolchildren” with a byline attributed to one of their teachers.

So after the death of their mother, Orville and Wilbur set about building a new printing press. Well, it was “new” to them, anyway — it was made from a broken tombstone, parts from an old buggy, and other miscellaneous bits and bobs. The brothers were immediately successful, thanks in part to their prior knowledge of the industry, but also because they had an immediate injection of regular business. Buoyed by a partnership with the Church of the United Brethren, they expanded their printing house, built a second press, and accepted at least one contract to build a similar press for another business. With commerce booming, the young entrepreneurs began billing themselves as the “Wright Brothers.”

This was about the same time a new transportation craze was sweeping across the US. It was called “wheeling,” and it came about with the invention of what was then called the safety bicycle. It’s basically the bicycles we know today, with two wheels of similar size. Wilbur and Orville were both passionate cyclists, regularly going on long trips and even winning cycling races.

Their mechanical aptitude allowed them to do what many people can only dream of: turn their passion into their livelihood. After friends and fellow cyclists started asking them for help in repairing their bikes, the Wright brothers realized they could build something better. So they did. In addition to their old printing press and their new repair business, they started building two models of bikes, each named after early Ohio pioneers. The Van Cleve was their high-end model, named for their great aunt, Mary Van Cleve, who had been the first person to set foot on the land that would become Dayton, Ohio. They also had a St. Clair model that was more accessible.

The Wright Brothers were again successful, but it was just one more stepping stone in their life’s pursuits. That next step is the logical continuation of an adventurous biker’s mindset. Hopping on your bike, heading off on a grand trip, cresting a hill and speeding downwards… well, it’s a little bit like flying, isn’t it?

Aerodromes and dirigibles and ornithopters… oh, my!

The Wright Brothers were far from the first people to fly, to look down and see the ground passing far beneath their feet in what had to be an experience both exhilarating and terrifying. Even as they were busy designing and building their own bicycles, the headlines were captured by news from the burgeoning world of aeronautics. At the time, it was all highly experimental, and there were a lot of failures, but none captured the Wright Brothers’ imagination like that of Otto Lilienthal.

Lilenthal was a German aeronautical engineer responsible for developing groundbreaking theories, like the idea that a curved wing shape would provide more lift than a flat wing. He wasn’t just a theorist — he designed 16 different versions of gliders and took them on almost 2,000 flights… albeit, brief flights. It was cutting-edge work for the time, but the limitations of the gliders became tragically clear on August 9, 1896. Lilienthal was flying in one of his monoplane gliders when it was caught by a sudden gust of wind. The nose was pushed upwards, his forward momentum was stalled, and he died the following day after breaking his spine in the ensuing crash.

As newspapers reported on the death of the aviation pioneer, Wilbur sat vigil beside his brother. Orville had contracted typhoid fever — bedridden for several months, it wasn’t until October that he was lucid enough to understand what his brother was telling him about Lilenthal’s death and the engineering mysteries behind it. The crash illustrated just how vital it was to maintain control over a flight path, limiting the impact of external factors like rogue wind gusts.

While Wilbur had nursed his brother through his potentially deadly illness, he had returned to that forgotten interest they’d had as children. Wilbur headed to the library to find books on the principles of flying, and when Orville was once again coherent, they agreed: it was a lack of control that had led to Lilenthal’s death. That was something they might be able to work on.

As it turned out, the timing was fortuitous. The popularity of bicycles meant more and more companies were beginning to mass-produce them, and smaller businesses like the Wrights’ were being boxed out of the market. Even though Orville assured his father they were doing fine and business was booming, they saw the writing on the wall. So when word got out that the US government was throwing obscene amounts of money at the research of manned flight, it became clear which project deserved their attention.

It was Wilbur who came up with the idea of adjusting the wings of a craft to capture wind and guide it, leading them to design a kite with controls that allowed them to twist the wings. It worked exactly like they’d planned, and Wilbur — who hadn’t been able to wait until Orville returned from a camping trip to try their kite — hopped on his bike, headed out into the woods, and told his brother they’d cracked it.

Off to Kitty Hawk

Anyone who has been to Ohio knows that it’s pretty flat, making it an inelegant location to test experimental aircraft. The Wrights needed another plan, so they reached out to the US Weather Bureau and asked for test locations that could give them elevation, wind, and preferably a soft place to land. Among the suggestions was Kitty Hawk, North Carolina: a village that had a decent average wind speed, high dunes to launch from, and — because the brothers had no illusions about what they were attempting — sand that would offer a much more forgiving landing than most other surfaces. So they headed off to Kitty Hawk, and yes, their family was understandably worried — so worried that their father made them promise to never, ever, both get into the plane at the same time. A crash in which he lost one son would have been tragic; losing both sons would have been too much to bear. The brothers ultimately kept their promise, only taking one single flight together in 1910.

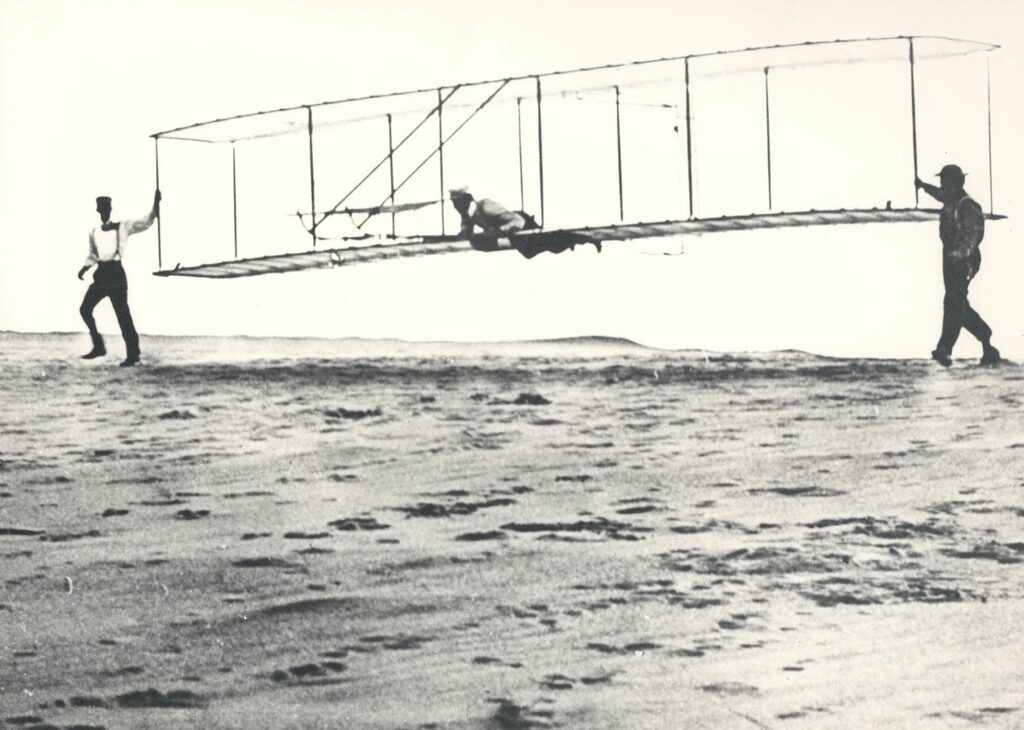

Their first biplane lifted off in 1900, but this attempt was more of a kite than a manned glider. Flying it unmanned allowed them to make observations and adjustments, and in 1901, the new and improved model was ready to go. Four miles outside of Kitty Hawk, the brothers flew between 50 and 100 glides, but still weren’t happy with the progress they’d made in the area of control.

Realizing they needed more information, the brothers constructed their own wind tunnel to test various shapes, sizes, and wing configurations. Their third glider really was spectacular, and they flew hundreds of manned flights, built a control system, and added a rudder. Finally, it was time to throttle up on the power.

The Wright Brothers recruited a machinist who had worked with them on their bicycles, a man by the name of Charles Taylor. Together, they built a combustion engine and propellor system, and it was this first powered, manned, fully-controlled flight that changed the world. The first flights lasted less than a minute, but by 1905, they had perfected not only their technology but their own skills to the point where they could stay in the air for a maximum of 39 minutes.

It wasn’t long before they realized that solving those first mysteries of flight wouldn’t even be the most difficult challenge they would face. The brothers had trouble convincing people to believe their flights were even possible. The brother set off on a series of demonstrations, securing funding from the US Army and a group of French investors for continued experiments. In 1908, the US Army offered them $25,000 for a plane that could fly at least 40 miles per hour, and carry a passenger as well as a pilot. They got to work.

The Wright Brothers’ success came fast, and in the following years, Wilbur flew demonstrations for audiences across Europe and America. By 1909, they incorporated the Wright Company, and the Wright Exhibition Company came a year later. Innovation and hands-on development soon gave way to other matters, ones that had become more pressing: Wilbur was soon more occupied with protecting their intellectual property and the rights to their invention, involving the company in scores of lawsuits; much later, they would be accused of delaying the advancement of the very science they worked so hard on.

Only three years after the establishment of the Wright Company — on May 30, 1912 — Wilbur suddenly passed away. He had contracted typhoid fever and was exhausted by the toll the company had taken on him. Orville only remained with the firm they had established for another three years; he sold his portion of the company to investors. Not long after — on April 3, 1917 — Milton Wright died in his home, peacefully, at 88 years old.

Orville continued to remain active in the field, consulting with the government throughout the world wars, and serving with organizations like the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics and the Daniel and Florence Guggenheim Fund for the Promotion of Aeronautics. It wasn’t the preferred life of the brother that had once been known as the shy practical joker, and for much of his remaining years, he chose to spend the majority of his time with friends and family in Ohio, or in his Ontario vacation home.

Orville also embarked on a long-standing feud with the Smithsonian, who had publicly claimed in 1914 that it wasn’t the Wright Brothers after all who had conducted the first manned flight, but Samuel Langley. Determined not to allow their achievements to be overshadowed, Orville fought not just for the retraction that came in 1928, but for an apology — one that wasn’t given until 1942.

Six years later — on January 27, 1948 — Orville had a heart attack. He died three days later, on January 30. By then, he had seen incredible things: their invention, beginning with their first experiments in controlling a kite over their sleepy hometown, had taken on a life of its own. By his final decade, the bombers of World War Two were changing history yet again.

For all the impact Susan Wright had on her children, she never lived to see them change the world, or even fly. Milton did, and he, like his children, eventually took to the skies; he was 82 years old when he got into a plane, for the first and only time, with Orville behind the controls. As they took off, he shouted from the passenger seat: “Higher, Orville, higher!”

And they went higher.