With the electrification of America fully underway during the late 19th century, the country had to make a choice between AC and DC. Each had its own set of advantages and disadvantages, and there was only room for one.

There was a lot of money at stake. Neither side wanted to back down, and when the opportunity arose, they were willing to play dirty. And thus, the War of the Currents began.

George Westinghouse

The War of the Currents is often touted as a fight between Edison and Tesla. That’s understandable. They were arguably the most prolific and famous inventors of their day. They had a bit of a rivalry going on, and they had clashing personalities—Edison was a public figure and a successful businessman, while Tesla was an eccentric recluse and much more of a mad scientist archetype. From a storytelling perspective, it made perfect sense to pit them against each other.

Reality, however, has little regard for good narrative structure. While Tesla certainly played a pivotal role in ensuring the supremacy of alternating current, the rivalry mainly concerned Thomas Edison and a man named George Westinghouse, or, to be specific, their companies – the Edison Electric Light Company and the Westinghouse Electric Corporation.

We’re not going to examine the early lives of Edison and Tesla because we’ve already done full-length bios on both of them that you can check out if you want to learn about what they did before the War of the Currents kicked off. We are, however, going to take a look at George Westinghouse since he doesn’t really enjoy the same kind of renown as the other two.

George Westinghouse was born on October 6, 1846, in Central Bridge, a small village in Schoharie County, New York. He was the eighth child of George Westinghouse Sr. and Emmeline Vedder. There is no doubt where George Jr. got his tinkering skills from. His father was a farmer by trade, but was deeply interested in machinery of all kinds. One day, he saw a threshing machine that his neighbor had just purchased, and immediately thought he could make it more efficient. He began writing down ideas and drawing new designs and, soon enough, took out a few patents. Although he was entirely self-taught, George Sr. became a successful inventor, so he left the care of the farm to hired hands and opened a shop to work on building machines full-time.

George Jr. took after his father, developing a passion for the intricacies of mechanics from an early age. There was nowhere else he would rather be than the family shop. School didn’t particularly interest him. Neither did sports, nor played games with the neighborhood kids. At first, his father forbade him from spending so much time in the shop, wanting him to have a more traditional upbringing. However, this did nothing to dull George Jr.’s dedication, so, eventually, Westinghouse Sr. relented.

Eventually, the family and the business got too big for Central Bridge, so in 1856, they were both moved to Schenectady. In the new factory, George had his own little workshop in the loft of the building where he tinkered away at various gadgets and gizmos that struck his fancy. When he was 13, he figured out that work isn’t free, so he asked his father for a salary. George Sr. agreed to pay him 50 cents a day, as long as he worked on stuff that was actually useful and not just his fanciful machines.

His father worried that George Jr. was too lazy and absent-minded to become a good worker. His attention often wandered, and he dropped his tasks to tinker with some model engine or intricate water wheel that sprang up in his mind, and he would get lost in this new project for hours until suddenly, he lost interest and moved on to the next thing.

In 1861, the American Civil War broke out, and George and his older brothers were struck with the patriotic urge to fight for the Union. Their father, although not opposed to the idea, believed the war would be over shortly and told them to have some patience. The older brothers did. George…did not.

One day, he hatched a plan to run away with a friend and join the army. His plans were thwarted, though, as his parents found out in time and his father caught up to him just as the train was getting ready to leave the station. He took the boy home, but to George’s surprise, there were no reprimands in store for him. Instead, his father informed him that he was free to go once he was a bit older, if he so wished. Probably because George Sr. didn’t believe the war would still be going on by then, but he was wrong.

Soldier, Inventor, Railroad Tycoon

In 1863, George Westinghouse was 16 years old and the Civil War still raged on. His older brothers had already enlisted, so, with his father’s permission, George joined the Sixteenth New York Volunteer Cavalry. His time with the unit was fairly uneventful and mainly involved scouting duty. In December 1864, he had a reunion with his brothers when all three received furloughs to spend Christmas with their family. They met up in New York City, but before they could head home, eldest brother Albert was told that he had to return to camp immediately and leave for New Orleans. A couple of weeks later, the family received word that Albert Westinghouse had been killed at the Battle of McLeod’s Mill in Mississippi.

Despite the tragedy, George was still eager to serve. He did, however, want to make better use of his engineering skills, so he transferred to the Navy and, after passing an exam, was made Acting Third Assistant Engineer and sent aboard the USS Muscoota. He was later moved to the USS Stars and Stripes, where he spent the rest of the war, blockading port cities with the Potomac flotilla.

Following his discharge, George Westinghouse enrolled in Union College but dropped out during his first term. He simply didn’t thrive in that structured environment, so he went back to work at the family factory. Soon after that, he had his first Eureka moment on a return trip from Albany, while watching a railroad crew painfully trying to get a train car back onto the track. This was a common problem back then, but Westinghouse felt that it could be solved much more efficiently by clamping another pair of rails onto the track and running them at an angle so they come up even against the wheels of the derailed car.

Westinghouse decided to create a car-replacer to do just that. His father, however, not interested in getting into the railroad business, refused to loan him the money he needed, so Westinghouse had to find additional investors. His device was successful, and he also invented a new type of frog, not the amphibian variety, but rather the crossing component that allows train wheels to move on either of two tracks while exiting a railroad switch. As a major bonus, while on one of his business trips to develop the frog, Westinghouse met the woman he would spend the rest of his life with – Marguerite Erskine Walker. The two got married in 1867, were together for 47 years, and had one child – George Westinghouse III.

Everything in Westinghouse’s life was coming up Milhouse, and things were about to get even better because in 1869, he came up with his first truly revolutionary creation – a new railway braking system.

Stopping trains back in the mid-19th century was a dangerous and arduous task. At first, it was done by hand. Brakemen would sit on top of the cars and turn control wheels, which applied the brakes to each set of wheels individually. This meant that they had to leap from one car to the next as fast as possible to turn all the wheels, and they had to do it in motion, at fairly high speeds, sometimes in bad weather. And let’s be honest – those early trains didn’t have the smoothest ride in the world. Injuries and even death from falling off the cars were a frequent occurrence.

Then the straight air brake system was invented, where compressed air pushed pistons that were linked to brake shoes that slowed down the wheels. The problem with this system was that all the pressurized air came from a compressor in the locomotive, and it had to travel from car to car through the same train line. A fault anywhere in the line caused a loss of air pressure that stopped all the brakes from working, and suddenly, you had a runaway train on your hands.

But then came George Westinghouse, whose eponymous air brake had once been dubbed “the most important safety device ever known.” At the heart of his invention was a triple control valve, which was fitted to every car and locomotive and could control the different air pressures in the braking system. Besides the valve, each rolling stock had its own air reservoir, so one fault wouldn’t bring down the entire braking mechanism. And the most clever bit – the braking was activated by a reduction in air pressure rather than an increase. This meant that, even if the braking system failed and lost pressure, instead of having a speeding train out of control, it simply slowed down to a halt.

Westinghouse’s creation immediately outclassed any alternative and became the preferred braking system for trains everywhere. In 1869, he founded the Westinghouse Air Brake Company in Pittsburgh to manufacture his invention and auxiliary equipment. Two decades later, he moved the company to Wilmerding, Pennsylvania, because he needed the extra room, and by the turn of the century, his air brake had been fitted to almost 90,000 locomotives and 2,000,000 train cars.

AC vs DC

Westinghouse’s air brake design kept him busy for a decade or so, especially since he kept improving it. Plus, he also founded an affiliated company called Union Switch & Signal that produced new systems for track switching and signalling.

But, of course, that’s not why we’re talking about him today, but rather his work with electricity. It was only normal for a man of Westinghouse’s disposition to get involved with the most exciting innovation of the day, and electricity was it, especially when it came to new lighting systems. Gas lighting was on its way out, and electric lighting was coming in. As he always did when he wanted to enter a new field, Westinghouse launched a new company to focus on his electric pursuits. In 1886, he founded the Westinghouse Electric Company, but little did he know that this endeavor would put him in the crosshairs of the most famous inventor in the country, Thomas Edison.

By the time Westinghouse got his company off the ground, Edison had already been in the game for almost a decade, and his direct current was already lighting homes in New York City using Edison’s famous incandescent bulb. Given the inventor’s reputation, influence, and financial backing, it might have seemed foolhardy to go against him.

But Westinghouse understood the limitations of direct current. In a DC system, the current flows consistently in one direction, at the same intensity. However, as the distance increases, so does the voltage drop, so direct current cannot travel very far. In Edison’s time, the operational range was about a mile, so to fulfill his vision of powering a whole city with direct current, you would have to litter it with power plants and generators. After a few years of only direct current, people began thinking that there might be a better way.

Two of those people were a French electrician, Lucien Gaulard, and an English engineer, John Dixon Gibbs. As early as 1883, they patented a system in Great Britain to distribute alternating current using transformers. Although to give proper credit, their work was based on a more primitive design made by a few Hungarian boffins – Ottó Bláthy, Miksa Déri, and Károly Zipernowsky – who worked for the Ganz Company in the Austro-Hungarian Empire.

Unlike its direct counterpart, alternating current reverses its direction…a lot…60 times per second is the standard in the United States. The transformer is the magic ingredient that allows us to take advantage of this property. One transformer at point A could increase the voltage substantially as the current begins its journey across power lines, and then a second transformer at point B could bring it back down to safe levels before the current enters your home. In practical terms, this meant that AC could travel a lot further than DC. It was also cheaper to install and maintain, since AC used overhead power lines, while DC relied on heavy copper wires that were buried underground.

With those properties working in its favor, it’s not surprising that Westinghouse wanted to get in on the ground floor of what he predicted to be an electric revolution. And he was ready to pay top dollar for it. When he sent his lawyer, Franklin Pope, to England to secure the patent rights for the United States from Gaulard and Gibbs, Pope simply asked him how much he should pay, to which Westinghouse replied: “They’ll tell you their price. Whatever it is, close the bargain, and I’ll send the money by cable to you.”

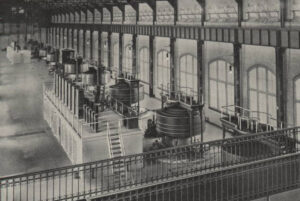

Ultimately, although the Gaulard-Gibbs transformer was a solid start, the conversion ratio still wasn’t good enough for practical purposes. It was up to Westinghouse’s chief engineer, William Stanley, to develop a transformer that could be used commercially. And he succeeded. In the spring of 1886, Stanley constructed a dozen or so transformers that reduced a five-hundred-volt main line to one hundred volts for secondary lines. And the town of Great Barrington, Massachusetts, became the first place in the world to be powered by this revolutionary new system…because that’s where Stanley’s laboratory was. DC had just made a powerful enemy, but it still had plenty of fight left in it.

Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap

By the end of 1887, the Westinghouse Electric Corporation had built over 60 AC power stations, but this was still about half what Edison had, and it certainly didn’t look like the Wizard of Menlo Park had any intention of backing down.

Edison had an ace up his sleeve, and that was the perceived danger of alternating current. All those high voltages traveling around the city were a recipe for disaster, in his eyes, and he wrote in 1886 that “Westinghouse will kill a customer within six months after he puts in a system of any size.” He likened direct current to a “river flowing peacefully to the sea,” whereas alternating current was “like a torrent rushing violently over a precipice.”

Edison and his supporters ran a propaganda campaign against AC, promoting it as the “killer current.” They even tried to turn “getting Westinghoused” into an idiom, meaning “to get electrocuted.” Their goal was to turn public opinion against AC by making them associate Westinghouse and alternating current with danger and death. In what is sometimes touted as the most shocking moment of the rivalry, no pun intended, Edison even electrocuted an elephant to show the world just how deadly alternating current truly was.

This popular “internet fact” only has a kernel of truth to it. Indeed, on January 4, 1903, a female Asian elephant named Topsy was put to death via electrocution in front of an astonished audience at Luna Park in Coney Island. And yes, people from the Edison film company were present to record the event and released a short film showing the gruesome scene titled Electrocuting an Elephant.

That’s about it, though. For starters, Edison had no involvement in the decision to euthanize Topsy, nor was he present for the execution. Men who worked for his movie company were there as part of the press, simply to record this unusual event. And it definitely did not have anything to do with the War of the Currents because it happened in 1903. The war was long over by that point, and AC had won decisively. Spoiler alert, by the way. The Edison Electric Light Company didn’t even exist anymore, as it had merged with another company to become General Electric. Thomas Edison had sold all of his company stock following the merger, so he had no interest in criticizing alternating current anymore.

No elephants might have been harmed in the War of the Currents, but other animals were. Dogs, mostly, since they were easy to come by, but also cattle and a few horses were all electrocuted to show the world the dangers of AC. Most of this ghastly work was done by a New York electrician named Harold P. Brown. He started his anti-AC crusade of his own volition, and Edison, recognizing a useful pawn when he saw one, began aiding him from the shadows.

Brown publicly staged his twisted demonstration for the first time in July 1888 at Columbia College. His unfortunate victim was a Newfoundland mix who was shoved in a cage with wet cotton and copper wires wrapped around his paws. His audience initially wasn’t sure what they were about to witness, but as Brown kept giving his spiel about the differences between AC and DC, a sense of uneasiness filled the auditorium. Then, when he had finished speaking, that uneasiness turned to horror as Brown began shocking the dog. First, he gave it a few pulses of DC current, which was not lethal, just incredibly painful, and then a jolt of AC, which killed the poor animal.

To Harold Brown, this was a job well done, and he repeated his experiment dozens of times for good measure. Eventually, he moved up to calves and even horses to drive his point home, although we all know that this did not deter the widespread adoption of alternating current.

Shocking dogs and horses was one thing, but there was an even better way to make the public associate alternating current with danger – use it to electrocute a person. Specifically, a convict who had been sentenced to death. Then came along Alfred P. Southwick, a New York dentist who developed the electric chair. Southwick had no stake in the Current Wars. He thought that the electric chair would be a faster and more humane alternative to other methods of execution, such as hanging. However, he wrote to Edison asking him for advice.

Initially, the inventor refused to have anything to do with it, being a staunch opponent of the death penalty. But then he realized that newspaper headlines all across the country would say something like “Alternating Current Kills Convict” or “Westinghouse Generator Used in First Electric Execution.” That’s the kind of publicity you can’t pass up.

With Edison’s support, the New York legislature authorized the use of electrocution in capital cases. Unsurprisingly, he advised that alternating current should be used, applied through the arms. Harold Brown’s experiments with animals were put forward as evidence of the increased lethality of AC over DC. And then, on August 6, 1890, a convicted murderer named William Kemmler had the dubious distinction of becoming the first person executed in the electric chair.

Edison’s anti-AC campaign was in full swing during the late 1880s. But George Westinghouse had a secret weapon of his own…a very clever inventor by the name of Nikola Tesla.

AC Wins

In order to remain competitive against a shrewd opponent such as Thomas Edison, Westinghouse was willing to spend, spend, spend. His goal was to own all the patents necessary to build a fully integrated AC system, so he went on a spending spree. Sometimes, when the patents were unavailable, he would purchase the entire company that owned them. That’s what he did with Consolidated Electric Light, so he could get his hands on the Sawyer-Man stopper lamp and produce incandescent lighting without infringing Edison’s patents. However, it was the patents for a polyphase AC induction motor and power transmission that Westinghouse bought from a man named Nikola Tesla that really tipped the scales in his favor.

Tesla had worked for one of Edison’s companies for a short while. He left on bad terms, although the exact reason why has never been fully established. Some say it was a disagreement over money. Others, that Edison wasn’t interested in developing Tesla’s plans related to alternating current.

Once he was solo, Tesla kept working on his ideas and, in 1887, he filed for seven patents comprising a complete system of generators, transformers, transmission lines, motors, and lighting. The following year, Westinghouse found out about this intrepid inventor and made him a very generous offer for all of his patents related to the induction motor: $60,000 in cash and stock, plus royalties, plus a hefty one-year salary as a consultant for Westinghouse’s electric company.

Tesla’s AC patents were, by far, his most profitable endeavor. Now an independently wealthy man, they allowed him to rent his own private laboratories in Manhattan and pursue his true calling as a comic book supervillain who built earthquake machines, death rays, and all that other fun stuff…Allegedly.

For Westinghouse, his lavish spending spree was a big risk, one that almost cost him his company. When the Panic of 1890 hit, his investors all rushed to call in their loans, leaving Westinghouse a temporarily embarrassed millionaire with a serious cash flow problem. It got so bad that he had to take out a mortgage on his estate to secure a new loan and keep the lights on at his electric company.

The gamble paid off, though, as alternating current emerged triumphantly from the War of the Currents. Especially after AC power lines began being moved underground, thus mitigating their danger and their biggest drawback. We’d like to end in a more dramatic fashion, but that’s simply not what happened. The reality was that more and more people, including among Edison’s supporters, saw that alternating current was the way forward…and then backward…and then forward again.

By the early 1890s, Thomas Edison wanted out of the lighting business. Ostensibly, this was because he was ready to move on to something else, but perhaps he simply saw the writing on the wall. His financial backers insisted they were losing money by sticking only with direct current. Ultimately, Edison lost control of his company, and it merged with the Thomson-Houston Electric Company to form General Electric in 1892. Now under the command of business magnate J.P. Morgan, the company switched over to AC, thus officially ending the War of the Currents, not with an all-out battle or a knockout blow, but with the stroke of a pen.