The “Spanish” flu pandemic was the single worst disease episode in modern world history. In the space of eighteen months in 1918-1919, its four epidemic waves killed tens of millions of people around the globe, ravaging a population that had already been exhausted by the mass killing tactics of the War to End All Wars.

In today’s video we will look at the Spanish flu from three perspectives: first, how did it spread across the world and what was its impact on the every day lives of ordinary individuals; then, we will profile this invisible killer, seeking to understand its origins and murderous methods; finally, we will assess the death toll it inflicted on the human species and see what can we learn from the experience.

And with that, let’s get into it.

Part I: Long March of the Invisible Tyrant

A Mysterious Origin Story

The term ‘Spanish’ is of course a misnomer, it would be more appropriate to call it ‘The Great Influenza Pandemic of 1918-1919’, so I will use both terms. This epidemic did not originate in Spain, it received this honorary citizenship only because Spain was a neutral country in WWI and its press was free from censorship to report first about this mysterious disease.

The origins of the pandemic lay elsewhere.

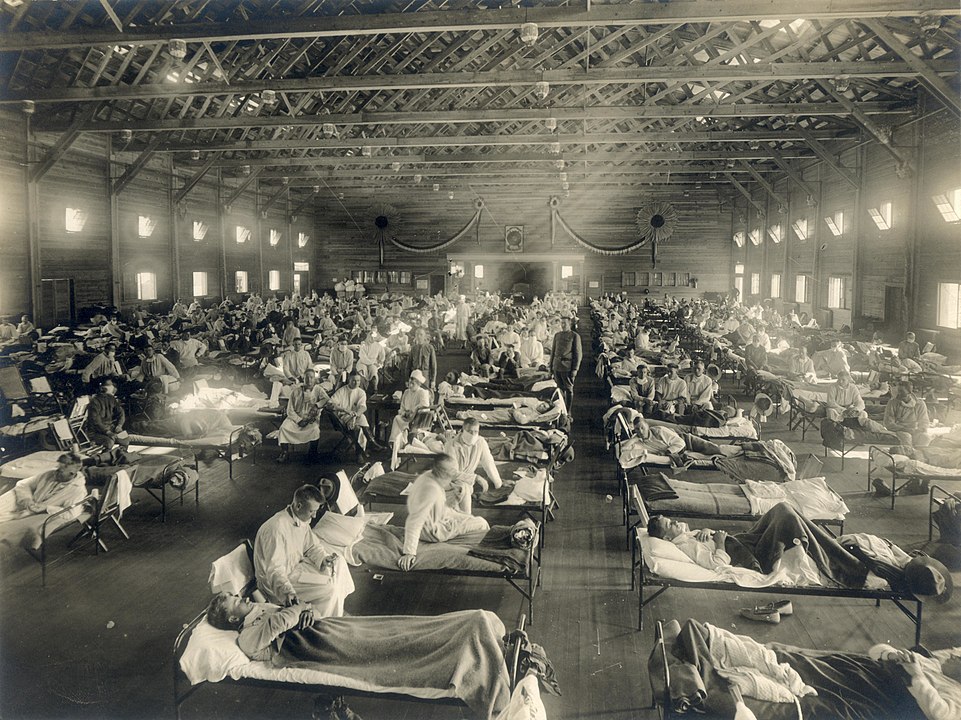

Most contemporary accounts place the first outbreak at a US Army training base, Camp Funston, in Kansas, in mid-March 1918. It is here that this flu virus reaped its first 48 victims.

But we will never know for certain if that was the true starting point.

The Online Archive of California holds in their Spanish Flu section a letter written by a young recruit, Roy, from Camp Logan, Texas. On the 1st of March 1918 he laments:

“We played another funeral today, one of the lads from Company 1 died, I knew him real well.”

‘Another’ funeral on the 1st of March? It seems like young soldiers had been dying throughout February then. But the origins of the great flu can be traced back even earlier than 1918.

As early as 1916 and 1917 army camps in Étaples, France and Aldershot, England had been ravaged by an unknown respiratory disease. At the time it had been described as ‘purulent bronchitis’, but its symptoms resembled those of the Spanish flu. However, these outbreaks did not spread beyond the two military bases and had died down by April 1917.

Historian Mark Humphries of Canada’s Memorial University of Newfoundland in 2014 proposed another origin story. Humphries found archival evidence that a respiratory illness that struck northern China in November 1917 was identified a year later by Chinese health officials as identical to the Spanish flu.

From China, British officials organised the transport of 94,000 labourers to the Western Front, via North America, as part of an auxiliary corps in charge of digging trenches and maintaining supply lines. The labourers were sailed to Vancouver on the Canadian West Coast, then loaded onto trains to Halifax on the East Coast, from which they could be sent to Europe.

The press was forbidden from reporting on these transports and the trains had been sealed: both were meant as a precaution, to protect the labourers from widespread anti-Chinese sentiment. But the un-intended effect may have been to further contagion amongst the auxiliary’s ranks.

Some 3,000 of them, while travelling through Canada, were quarantined with flu-like symptoms. And of course, newspapers could not publish a single word about it, meaning the infected trains could continue their eastwards run.

The Chinese laborers arrived in southern England by January 1918 and were sent to France, where a Hospital at Noyelles-sur-Mer recorded hundreds of their deaths from respiratory illness.

Whether because of the Chinese Labourers, or US Army recruits, large movements of troops were accountable for the rapid diffusion of the virus. Between May and July the Great flu had spread across virtually the whole of North and Central America, Europe, and Asia.

The Pravda in Russia wrote that ‘The Spanish Lady’ had thrown a whole town, Murom, into disarray. The Times of India reported that

“Nearly every house … has some of its inmates down with [influenza] fever and every office is bewailing the absence of clerks,”

The epidemic had an obvious impact on the war, which was still raging especially on the Western Front. German General Erich Ludendorff complained that

“It was a grievous business having to listen every morning to the Chiefs of Staff’s recital of the number of influenza cases, and their complaints about the weakness of their troops.”

He would later even blame the failure of his Spring Offensive on the virus. This was the First Wave, which seemed bad at the time. And it actually was pretty bad. But it was nothing compared to what was to come.

Voices in The Second Wave

During the first sweep of the Spanish Lady, the influenza virus probably went through a mutation process which made it much deadlier. This enhanced killer made its first appearance in late August of 1918, when the Second Wave took off almost simultaneously from three major wartime ports: Boston, USA; Brest, France; and Freetown, Sierra Leone.

Form the three ports, thousands of sailors, soldiers and civilian travellers became vectors for the virus. Aboard their ship, in a matter of weeks the infected spread the disease across the four corners of the Globe, with only a handful of remote locations being spared the ordeal.

The Second Wave dragged down throughout the whole of Autumn and into early Winter of 1919. The end of the war, on the 11th of November 1918, did not mitigate the onslaught, arguably it made it worse: millions of soldiers were demobilised, hundreds of thousands of PoW’s returned home, carrying an unwanted stowaway inside their lungs.

A whole generation of young men had been decimated by artillery, weaponised gas, machine gun fire … and those who survived were likely to die because of a single droplet of saliva. It took only one single virus, inside a single droplet out of 40,000 ejected by a single sneeze … and like that, you were infected.

The feeling of the fragility of life in those times is captured by the every-day correspondence of ordinary people.

In September 1918 a Post Office worker in Plymouth, Massachusetts wrote to his wife about the gruelling conditions he worked in to ensure a continuing service, amidst the constant death caused by the flu:

“I have some more very bad news to write you and I guess if things keep on that by the end of the year there will be nobody left in town. Harold Ashley died yesterday …Harold will be buried just as soon as his body arrives and there will be no funeral. On Friday we had seven funerals and Saturday about as many, so you see what we are up against. In Brockton three days last week there was one every hour”

On the 11th of October, a recruit in training in Michigan wrote to a friend that in his camp ’50 die every day from it’

From the 16th to the 27th of October, a series of letter from Mrs Alma Sr to her daughter Alma Jr show how unbreakable can a mother’s love be. Writing from Rochester, New York, Mrs Alma worries that her daughter is safe and healthy, in her college in Ontario, Canada. Some of the motherly advice may resonate with what you hear these days:

“Was just wondering how you were getting in these days of epidemic – in the Country it is fierce and so many dying …

Over here is something awful people are dying and it’s awful …

Don’t worry or fret because you only can walk in the yard – be glad you can do that … keep in fresh air all you can … and keep warm put your bathrobe on at night … hot lemonade at night is excellent for influenza.”

Mrs Alma then laments that she cannot help her other daughter with her little baby, Jane because she is invalided at home, and that it is “impossible to get nurses”

While worrying about the well-being of her daughters and doing what she could to help her granddaughter, Mrs Alma was ill with cancer. Maybe unable to access medical care earlier because of the pandemic, she was eventually hospitalised on the 27th of October, and died on the 6th of November.

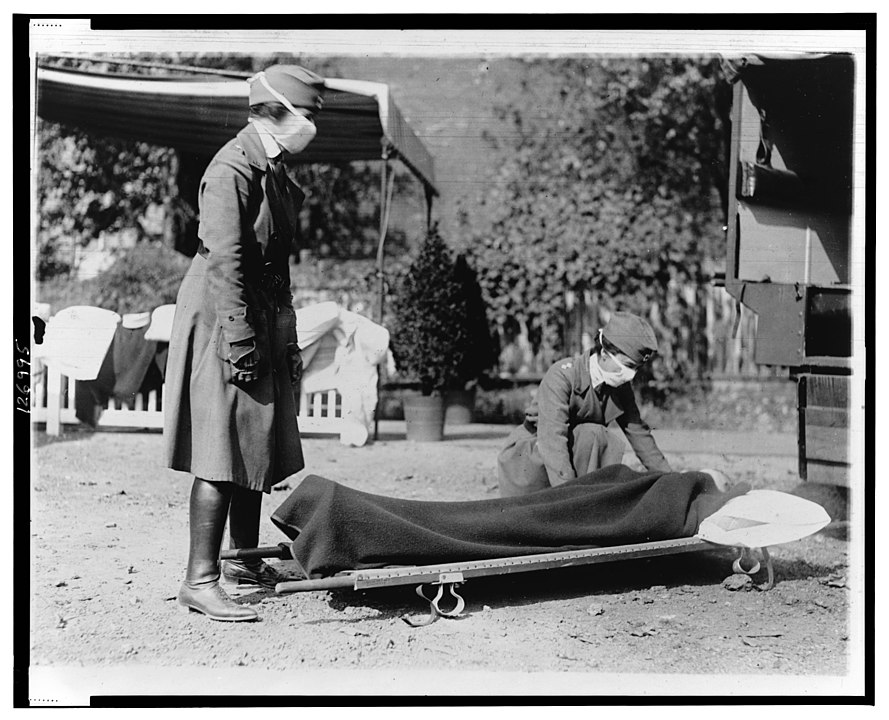

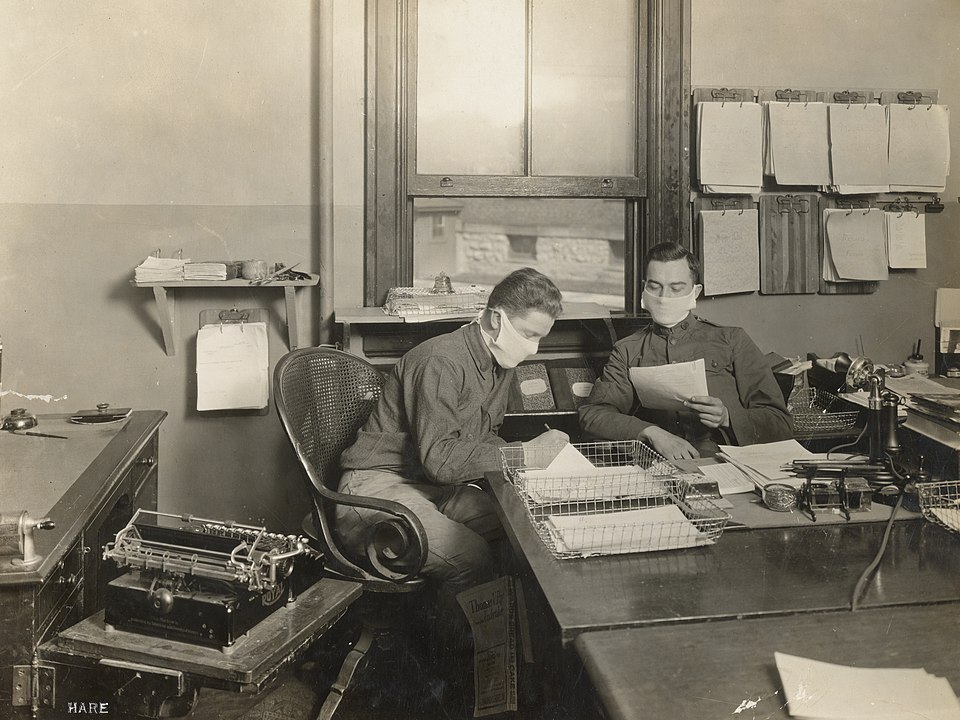

On the 31st of October, an official at the Mayor office of San Francisco took the initiative to notify his counterpart in Santa Barbara, about effective public health measures in his city.

“Sending this for your information because I have seen the whole terrible effect of epidemic here, because masks have saved untold suffering and many deaths, and because Santa Barbara is my old home city”

The measure in place was simply the universal wearing of masks. Three days after the use became general, new cases in San Francisco dropped by 50%, but the daily death toll was still above 100.

On the other side of the pond, London was being stricken as hard as New York State, California and Ontario. On the 28th of October 1918, one Mrs Bennett wrote “Things here are in a terrible state, this new flu … taking people off as they walk along the streets. In fact, the undertakers can’t turn the coffins out or bury the people quick enough. There’s families of 6 & 7 in one house lay dead.”

On the same day, an American soldier stationed in France wrote to his mother, reassuring her that the situation where he was stationed was not as bad as it was at another base, Camp Sherman. He also mentioned that “The French people have a way of treating [the flu], they make some kind of tea of some kind of leaves….”

Unfortunately, he did not provide the recipe.

The Last Waves

Another series of letters from an American private provides a good example of acquired immunity. Martin Aloysius Culhane, known as ‘Al’, was stationed at Camp Forrest, Georgia, form where he wrote to his brother and to his best friend. While he mourned the death of his ‘bunkie’, Thomas, he was in relative high spirit: he had survived the Great pandemic, not once, but twice!

“I am still in quarantine but will be released today. I am feeling great and the two day’s rest has done me a world of good”

His main concern was that while in quarantine he had been

“neglecting the ladies”.

So he asked his friend Cliff to check on Ursula, Ella, Ida, Mary Rose, Mary English and Mary Anne.

So, was ‘Al’ simply lucky, in love and in health? There is strong evidence suggesting that exposure to previous waves of the Spanish flu could generate acquired immunity in those who had been infected, but had survived.

A research led by Dr JM Barry from Tulane and Xavier Universities, Louisiana, highlighted how the First Wave of the Spanish Flu was characterized by a high number of cases, but had a lower fatality rate than the Second Wave. By looking at medical records of US soldiers, he estimated that the fatality rate during the lethal Autumn sweep was 4.7%. In the Spring, it had been only 1.1%.

However, the deadly barrage of the Second Wave had largely spared those who had been previously exposed in the Spring! The case of Camp Dodge illustrates this perfectly: Here, one regiment of troops had experienced the First Wave, while another regiment had escaped it. Among those exposed in the Spring, only 6.6% became sick with flu in the Autumn.

In contrast, among the troops not exposed in the spring, a staggering 48.5% fell ill during the Second Wave!

Now, the witness accounts and the research mentioned so far may refer to America or Europe, but this should not give the impression that other continents were spared.

Let’s go back to September 1918. This is when Indian troops who had served on the Western front returned home. The first outbreak took place in Bombay, where mortality rate was more than 5% of all population. The Spanish Lady had now access to access to a huge new territory, densely populated, serviced by a large railway network. The perfect storm, in other words. In just a month, the flu had spread to Sri Lanka and to the Northern provinces, reaping an estimated 14 to 18 Million lives, the highest death toll recorded in a single country.

Also in September, a troop transport ship sailed off Bombay to Mombasa, Kenya. Of course, the virus was a stow away. The infection spread to members of the Kenyan Carrier Corps, who were just about to be demobilised. As they returned home, they carried the contagion inland, adding to the death toll caused by the other two major African outbreaks, originating in Sierra Leone and South Africa.

Most of Africa had been spared the First Wave, meaning that the Autumn burst had cruelly scorched through the continent: towns like Kimberley, Addis Ababa, and Windhoek lost over 4 percent of their populations to flu. The bulk of the victims were aged between 18 and 40: so, the effect on society was disastrous in terms of loss of labour, reproductive capacity, and family structures. It was a sudden demographic, social and economic catastrophe without precedent.

Back in India, by November the rate of contagion had largely subsided. It is speculated that this was due to the onset of the monsoon season, as humid climates are not favourable to flu viruses.

The march of the invisible tyrant, nonetheless, continued eastwards, reaching China. Until now, the majority of the victims worldwide had been aged 15 to 34, an age bracket unusual for influenza pandemics. We’ll find out later why this group was particularly targeted. In China, the Second Wave preyed on an even younger cohort, children aged 11 to 15.

Overall, however, the mortality rate here was much lower compared to India and other Countries. Researchers from the Hong Kong Institute of Chinese Medicine theorize that traditional Chinese medicine may have played a part.

Remedies put in place by local government included spraying houses with limewater, or burning rhubarb and root stalks of the Atractylodes flower to disinfect the air. For prevention, villagers were advised to drink mung bean soup and rock sugar.

Another explanation is the one hinted at earlier: since the pandemic had originated there, Chinese citizens had already developed an immunity to it.

By the early months of 1919 the rage of the pandemic was relatively tamed, and I stress relatively. The early Spring of the year saw a third wave making the rounds throughout the globe. Although it did not match the speed, reach and virulence of the Autumn wave, it was still deadly. On March 5th 1919, a young Canadian man, Harold, wrote to a friend in Illinois:

“There are an awful lot of people dying just now on account of the flu. A little girl next door was buried today and there is a lady up the street that is pretty sick and my little sister is just getting over it … So I guess it is pretty near my turn …”

We don’t know if Harold made it or not.

The third sweep was followed by a Fourth Wave, less severe, which lingered on in locations such as Scandinavia, the South Atlantic and Sicily. It is still debated whether this was a mutated strain of the original virus, or a new one altogether.

One of the last documented victims of the Fourth Wave was a little girl from Palermo, Rosalia Lombardo. She had been born on the 13th of December 1918, at the height of the Autumn flu in Europe, and passed away aged only two, on the 6th of December 1920.

Her father, aggrieved by such a sudden and meaningless death, asked for her body to be preserved as if she were still asleep. One century later, Rosalia can still be seen sleeping in the Capuchin Catacombs of Palermo. This unwitting memorial to the Great Pandemic is now known as ‘the most beautiful mummy in Europe’.

Part II: Profiling the Killer

One of a Kind

At a high level, flu viruses are divided into four types, from A to D. And type A’s can be divided into further sub-categories, depending on the subtypes of two proteins present on their surface: hemagglutinin, ‘H’, and neuraminidase, ‘N’.

The influenza virus responsible for the 1918 pandemic was identified as being a Type A, H1N1 subtype.

Viruses of the A, H1N1 type are actually quite common amongst humans. But we’ll find out later what made this specific virus so special – and so lethal.

A 2001 study suggested that the 1918 virus may have originated in swine hosts, before moving onto humans. But another investigation in 2005 suggested a more likely source: birds. The enteric tracts of waterfowl such as ducks and geese are known to be the reservoirs for all known influenza A viruses.

For those of you not au fait with physiology or anatomy, the enteric tract is the nervous system that regulates digestion. Within the original host, let’s say a duck, the virus may mutate over time: either independently, or by recombination with a gene segment from a different virus.

Now that the pathogen is mutated, it is ready to jump species, usually from avian to mammal,

and attack a new type of cells, for example those lining the lungs.

This is almost certainly what happened to the Spanish flu strain, and I should stress almost.

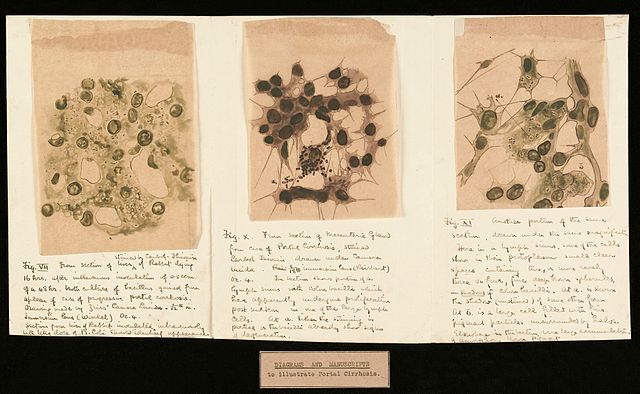

In two separate studies of 1999 and 2005, Oxford University and the Atlanta Centre for Disease Control were able to reconstruct the genome of the original virus.

What they found is that the 1918 influenza was composed of 8 gene segments, all distinct from any of the hundreds of both avian and mammalian viruses collected since 1917. This … little fella… was literally one of a kind! This unique quality made it impossible to ascertain who or what could have been the original host of the virus, and how it had evolved into its lethal final form.

Another clue: normally, outbreaks of viruses with an avian origin are preceded by large die-off of poultry or other bird population … but this was not the case for the 1918 pandemic.

The initial animal host, the patient alpha, is still unidentified.

Modus Operandi

One thing was clear about the 1918 H1N1 virus: its virulence and pathogenicity were unrivalled, compared to other viruses which both preceded it and followed it.

To clarify these points:

Pathogenicity is defined as the ability of an infectious agent to cause disease or damage in a host.

Virulence, on the other hand, is a measure of the severity of said disease. A microorganism can be pathogenic, or not. If it is pathogenic, its virulence can vary from mild to fatal.

Let’s look at pathogenicity first. Contemporary, ‘normal’ flu viruses require the presence of the enzyme trypsin in their human host, in order to replicate. The 1918 virus instead could proliferate even in the absence of trypsin, making it more pathogenic than other viruses.

The Spanish flu also displayed a unique capacity to proliferate at high rates inside human bronchial cells – and that explains its virulence. Little by little, a picture of the killer was emerging, thanks to modern researchers in the role of crime scene investigators, or criminal profilers. The next step was to understand how Mr Type A H1N1 of the 1918 class actually killed: what was its modus operandi.

Enter Dr David Morens of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in Maryland. In 2007 he reviewed autopsy records for influenza casualties in the 1918-1919 period and identified two overlapping syndromes which caused the death of the infected hosts.

In at least 85% to 90% of cases, patients suffered from an acute viral infection, that spread down the respiratory trait, causing severe tissue damage inside the lungs. The damaged tissue was then invaded by a so-called secondary invasion. Not viruses this time, but bacteria: pathogens like Streptococcus Pneumoniae or Staphylococcus aureus would invade the damaged lungs, causing cases of aggressive bronchopneumonia.

In other words, the killing virus did not act alone, but had accomplices. The actions of these cohorts eventually led to severe pulmonary haemorrhage and necrosis – or tissue death – within the bronchi.

The remaining 10 to 15% of fatal cases suffered from ARDS, or ‘acute respiratory distress—like syndrome’. Patients with this syndrome could be easily identified by their peculiar blue-grey facial discoloration: a typical sign of drowning. Because that’s essentially what was happening: the virus caused the pulmonary blood vessels to exude huge amounts of thin, watery droplets, which clogged the lung tissue. In other words: these patients were drowning in a liquid created by their own bodies.

Now that we have clarified the modus operandi of this killer, we have to understand its peculiar choice of victims. Normally flu epidemics claim most of their victims among the elderly, but the Spanish Flu had a clear predilection for a younger demographic, those aged between 15 and 34.

A lower than expected mortality among the elderly may have been explained by acquired immunity. Individuals aged 40 and over, may have been exposed to one of the three flu pandemics of the 19th Century, in 1830, 1847 or 1889. Although not everybody agrees: unlike the 1918 strain, these previous viruses did not cause aggressive bronchopneumonia nor lung haemorrhage.

We may have more convincing answers explaining why the death rate was higher among the young ones.

Dr Robert Snelgrove from Imperial College London, among others, has theorised the notion of the so-called ‘cytokine storm’. Cytokines are proteins released by cells to interact with each other and to trigger specific processes. For example, internal inflammation – a common reaction of the body against infections. A younger organism would naturally release more cytokines than and elderly one. In the case of the Spanish flu, the cells of infected younger patients released a deleterious excess of cytokines, leading to excessive inflammation of the lungs, and more importantly, tissue necrosis.

Ironically, younger, fitter organisms deployed a stronger reaction to protect themselves – a reaction which eventually claimed their lives.

Part III: Assessing the Damage

A Pale Rider

Shortly after the last wave had died down, the scientific community tried to take stock of the magnitude of the disaster. American bacteriologist Edwin Oakes Jordan was one of the first to calculate the death toll, which he estimated to be in the vicinity of 21.5 million.

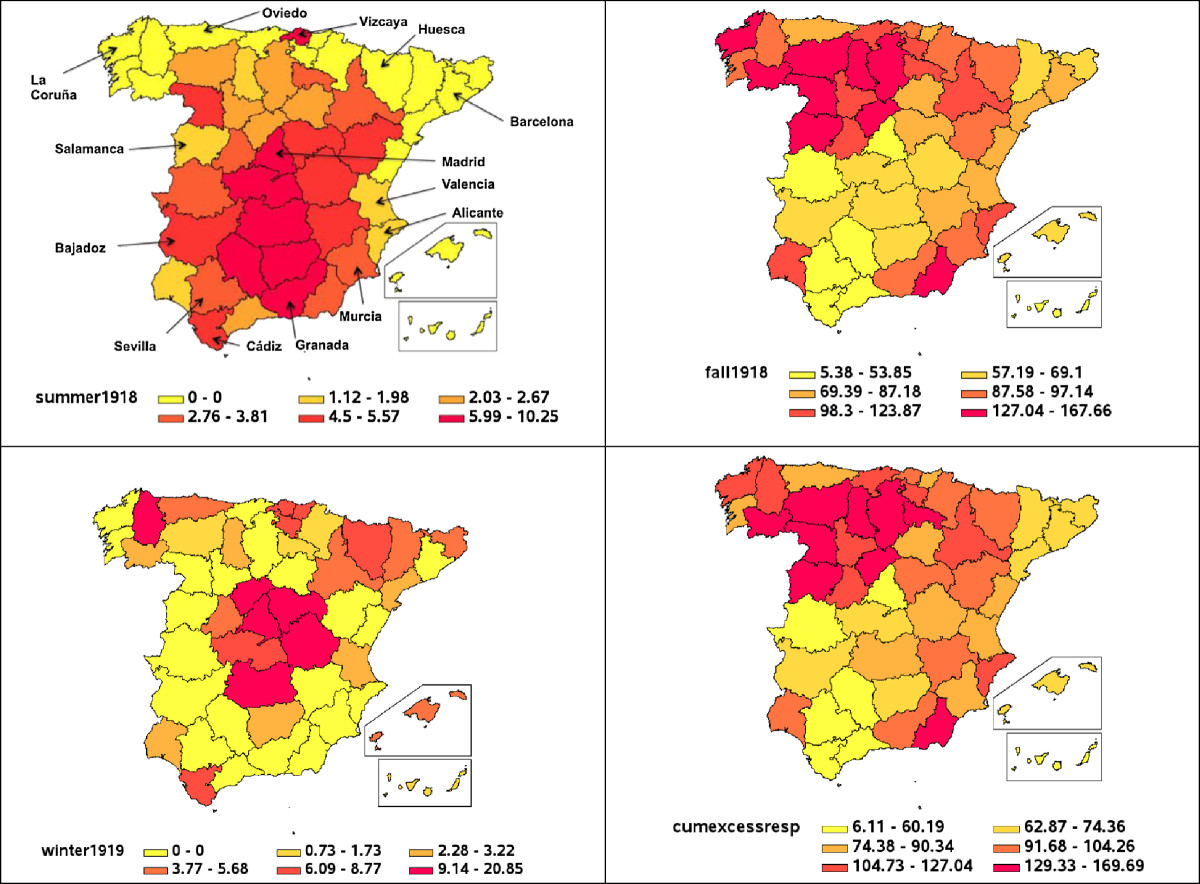

Credit: Gerardo Chowell, Anton Erkoreka, Cécile Viboud and Beatriz Echeverri-Dávila – http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2334/14/371#, CC BY 4.0

This number in itself is staggering. Compare it to the casualties of the Great War: about 10 Million dead soldiers, killed over a period of four years and a half. The Spanish Flu killed twice as many people over little more than a year.

Now let’s compare it to the world’s population in 1918. At that time there were 1.8 Billion on the planet. The Spanish flu killed 1.2% of them. If we apply that ratio to today’s population we would have a death toll of more than 93 million.

Oakes Jordan’s estimate stood for decades, but it was later challenged as being too low. First, a 1986 publication calculated the mortality in India alone to be at 18 million. Subsequently, in 1991 authors David Patterson and Gerald Pyle proposed another estimate, placing the death toll between 25 and 40 million victims.

Was that the definitive number?

Probably not. A 2002 study by Dr Niall Johnson and Dr Juergen Mueller suggested that previous numbers may have been underestimated due to common issues such as missing records, misdiagnosis or death certificates compiled by non-medical personnel.

Not only that: deaths among indigenous populations in colonial dominions may have been overlooked, ignored or simply not reported by colonial authorities. Also, most of the reports collected at the time of the pandemic referred to deaths taking place during the major wave of Autumn-Winter. Influenza mortality before and after that wave may have been ignored or reported under other causes of death, such as pneumonia.

All in all, considering all these instances of under-reporting, Johnson and Mueller placed their estimate in a range from 50 up to 100 million dead.

Let’s stop for a second to consider that. 100 million dead. The entire population of the US at that time was just 108 million. The whole of Latin America only had 57 million inhabitants.

Sometimes numbers may not be enough to represent the sheer scale of a tragedy, so think about it this way:

in a matter of few months, one USA or two Latin Americas had been completely wiped out by a microscopic being which had likely originated in the bowels of a duck.

In all honesty, the more we researched the death toll, the more we found conflicting accounts, ranging from the top count of 100 million, down to the no less tragic 18 million. We will likely never know how many people did not get to see their next year because of the Great killer of 1918 and 1919.

A Tragedy of the Unborn

In our grim research we also came across an even bleaker notion: how many victims didn’t even get to see their first day of life. In other words: the impact of the Great Influenza on unborn children.

Dr Bloom-Feshbach of Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, and her team have examined the relationship between influenza and birth rates during the Great pandemic in the US, Denmark, Sweden, and Norway.

The analysis showed a decline in birth rates for all examined populations in spring of 1919. This decline represented a 15% drop below baseline levels recorded before the pandemic. This ‘natality depression’ reached its maximum levels about 6 months after the pandemic peak of the previous autumn.

This suggested that the decline in birth could be attributed to a surge in first trimester miscarriages, which affected about 10% of all women who were pregnant at the peak of the pandemic. The conclusion of Bloom-Feshbach and team is that the virus was directly responsible for the miscarriages. And the 10% incidence rate may have been an underestimation. As they point out, a 1919 report of 1350 pregnant women with influenza, showed how more than a quarter of them had miscarried.

The concept of so many babies not even being born is hard to accept. But the same study revealed another finding, which shows that regardless of the disaster, our species is always capable of bouncing back up.

The dip in birth rates in spring of 1919 was followed by ‘a compensatory natality increase in late autumn 1919 and early spring 1920, when natality significantly exceeded the expected rates.’

The resurgence of births confirmed that fertility was not permanently impacted. Humanity could slowly rebuild itself, lick the wounds inflicted by the double tragedy of the Great War and the Great Pandemic, and slowly return to normal.

Return to a daily life, and a historical period that was going to be devoid of war, famine and disease, at least according to some leaders … a period which turned out to be only a 20-year truce. But that’s another story.

Could It Happen Today?

Back in 2004, a team at the Harvard School of Public Health had modelled the transmissibility patterns of the 1918 virus, more precisely they calculated its reproductive number, ‘R’, in relation to its serial interval, ‘v’.

The ‘R’ number tells how many secondary patients are produced by each primary patient. The ‘v’ value is the average time – expressed in days – between a primary and secondary case.

The team evaluated that the 1918 virus had an ‘R0’ value of 2 to 4. In lay terms: an infected patient could infect four more patients in less than a day. This may sound like a high rate of contagion, however the researchers pointed out that this was not that high, in relation to other influenza subtypes.

In their estimation, a similar pandemic could be prevented by vaccinating or administering antiviral prophylaxis to 50–75% of the population.

Sounds easy, right? Well, this depends on how well prepared a national health system is, when it comes to facing such emergencies. Stockpiles of vaccines and antivirals may or may not be enough – or these drugs may not be available at all, still progressing through the early stages of a clinical trial.

There is the added problem that flu viruses may be transmitted before the onset of defining signs and symptoms. In other words: people infect each other even before they appear to be sick.

So, what is left to do? I will quote directly from the clinical paper:

“This implies that measures that generally reduce contacts between persons, regardless of infection status, may be our most powerful protection against a pandemic until adequate vaccine and antiviral medicines can be produced, at which point mass-vaccination and prophylaxis may be more effective than targeted approaches.”

I hope that by the time you watch this video the current Covid-19 pandemic is a thing of the past. If it’s not, well I hope that this message resonated with you. You have heard it a million times, we all have heard it. Until we are through this emergency, staying at home is our most powerful protection. Stay at home, stay safe, and thank you for watching.

SOURCES:

Voices from the Pandemic

http://edition.cnn.com/2009/US/04/29/wwi.spanish.flu.letters/index.html

https://www.daileyint.com/mytimes/20ctry.htm

http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/firstworldwar/transcripts/aftermath/influenza.htm

https://www.gazettenet.com/Letter-Cheryl-Howland-33378371

https://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt2t1nf4s5/entire_text/

History of the Pandemic

https://books.google.co.uk/books?hl=en&lr=&id=ceZvDwAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PA9&ots=SisC2SI0-R&sig=8VePH_F4tN5RQuri3bjsXTjWa54&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2014/1/140123-spanish-flu-1918-china-origins-pandemic-science-health/

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1201971207000355

https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/influenza_pandemic

https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/influenza_pandemic_africa

https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/war_losses

Profiling the killer

https://www.cdc.gov/flu/about/viruses/types.htm

https://academic.oup.com/jid/article/195/7/1018/800918?searchresult=1

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11546876

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16208372

https://science.sciencemag.org/content/310/5745/77.long

https://academic.oup.com/jid/article/194/Supplement_2/S127/850776?searchresult=1

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15482206

https://academic.oup.com/jid/article/198/10/1427/856581?searchresult=1

Assessing the damage

https://muse.jhu.edu/article/4826

https://www.jstor.org/stable/201369?seq=9#metadata_info_tab_contents

https://academic.oup.com/jid/article/204/8/1157/816427?searchresult=1

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7095078/