American short-story writer O. Henry wrote about his years spent living in Texas as “fearfully dull, except for the frequent raids of servant girl annihilators who make things lively in the dull hours of the night.” And just like that, the author gave a name to one of America’s first boogeymen.

So who was the Servant Girl Annihilator? He was undoubtedly a monster, but one of flesh and bone, who prowled the streets of Austin, Texas, during the mid-1880s, armed with an axe, looking for fresh victims.

This was a new problem for America. The term “serial killer” wouldn’t even exist for over half a century. This was even before the infamous Chicago murder spree of H. H. Holmes, often incorrectly touted as “America’s first serial killer.” Neither the police nor the public knew how to respond to a madman who was going around seemingly chopping people up at random, just for the hell of it. And the Annihilator took full advantage of their confusion as he killed with impunity and then, when he had enough, he simply disappeared, never to be heard from again…

New Year’s Evil

During the early 1880s, the city of Austin, Texas, was considered a great place to live. What started as a modest cattle town with only a few thousand residents ballooned into a thriving and sprawling metropolis in just a few decades following the Civil War. But this would all change on New Year’s Eve, 1884.

It was the early hours of the morning, and somebody desperately started banging on the door of local insurance agent William Hall. He wasn’t at home, but his brother-in-law, Tom Chalmers, was, and he resented being dragged away from his warm bed. At the door, Chalmers saw Walter Spencer, a local laborer who was the partner of the Halls’ live-in maid, 23-year-old Mollie Smith.

It was clear that someone had viciously attacked Spencer. He was barefoot, his nightshirt ripped, and he was gasping for breath and struggling to stay on his feet, with a deep gash pouring blood from his head. He said that a stranger broke into their room, beat him unconscious, and took Mollie. He begged for help, but he found none. The Civil War might have ended slavery, but this was still Texas in the 19th century and both Walter Spencer and Mollie Smith were Black. To Tom Chalmers, the idea of going out in the dark and freezing cold to look for a missing Black girl was ludicrous. He didn’t even want to help the man slowly bleeding to death in front of him. He simply told Spencer to go get bandaged. Afterward, he escorted the injured man back outside and returned to bed. Whatever happened, it could wait until daylight.

Except that it couldn’t. By then, it was already way too late. The body of Mollie Smith was found near the outhouse. Her head had been hit with an axe so hard that it almost split in two, and the rest of her body was covered in stab wounds and cuts. There were ungodly amounts of blood, both where Mollie Smith was dumped and in the servants’ quarters where the initial attack took place. The murder weapon had been discarded in a pool of blood on the floor by the bed, and the killer left a bloody handprint on the wall by the door.

On the scene were the local physician, Dr. Steiner, and the Austin Police Department led by Sergeant John Chenneville, or “Ronnie O Johnnie” as he was known by the locals, a mountain of a man “built like an upright piano” with a booming voice, a thick mustache drooping over his upper lip, and a handshake strong enough to crack corn.

Although most of his days were spent dealing with drunk troublemakers who got a little too rowdy in the town saloons, Chenneville was also the one who investigated the few murders that did occur in Austin every year. He had seen his fair share of dead bodies, but even he was completely gobsmacked by the sight that waited for him at the Hall household. What had been done to Mollie Smith, Chenneville had never before seen done to another human being, only to cattle in slaughterhouses. Not even his trusty bloodhounds were of any help. The smell of blood so overwhelmed all other scents that they could not pick up any trails.

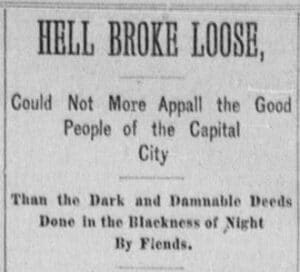

A few hours later, the newsmen started showing up after someone tipped them off about a dead body. Many Texas newspapers kept a bureau in Austin to cover state politics, so a media storm descended upon the Halls’ backyard, but that storm soon turned into a light drizzle when they laid eyes on what was left of Mollie Smith. Just like the rest, they had never seen anything so horrifying. Everyone just stood silent, with a few journalists even stepping away from the scene to avoid becoming physically sick. The Daily Statesman went on to describe this crime as “a deed almost unparalleled in the atrocity of its execution,” while another journalist called it “one of the most horrible murders that ever a reporter was called on to chronicle.” And little did they know that this was only the beginning.

A String of Attacks

The concept of a “serial killer” was foreign to people back then, so nobody thought at first that this could be some demented psycho who took pleasure in torture and murder. Everyone’s first suspicion turned to the most obvious candidate – the lover. Could Walter Spencer have killed Mollie and then tried to make it seem like they were both victims? This seemed unlikely. For starters, Spencer could have died from his head wound. Plus, everyone who knew him insisted that he was law-abiding, hard-working, non-violent, and completely dedicated to Mollie Smith.

Ok, so Spencer probably wasn’t the guy, but what about William “Lem” Brooks, Mollie’s ex-boyfriend? He had followed her to Austin, and when she rebuffed his advances, he almost got into a fight with Walter Spencer. He seemed like a much better suspect, so Chenneville gave the order to have him arrested. Eventually, Brooks was released due to a lack of evidence, but by then, everyone had already forgotten about the case. The sad reality was that, no matter how gruesome Mollie Smith’s death was, most people in Austin did not care about a poor, Black servant girl getting killed. They read about it in the paper once, gasped in horror, exclaimed out loud, “What is this world coming to?” and then went on with their day.

Clearly, this laissez-faire attitude toward murder emboldened the killer because, after a brief cooling-off period of a couple of months, he returned in full force, starting in March 1885. His next victim was another servant girl, a recent German immigrant who woke up one night to find a stranger staring at her before whacking her in the head with something hard. Fortunately for her, she had a good set of lungs on her, and her screams woke up the whole house and forced the man to leave before he could finish what he had started.

A few nights later, two other servant girls were woken up by the sound of somebody trying to force open the door of their quarters. In perhaps the stupidest move possible, one of them actually got up, unlocked the door, and went outside to see who it was. She was immediately grabbed by someone from behind, but again, the screams from her and the other girl caused her assailant to run away. Too scared to go back to bed, the two young women spent the night in the kitchen. When they returned to their quarters the next morning, they saw that someone had broken inside and ransacked the place. Clearly, their attacker had returned and became frustrated when he found the room empty. It seemed that the servant girls had evaded a grisly, painful death not just once, but twice in one night.

The next attack came just two nights later when the mysterious man broke into the home of a tailor named Abe Williams and assaulted his housekeeper. But, for whatever reason, he disappeared after striking her in the head a few times, leaving the woman with a few cuts and bruises, and shaking like a leaf, but alive.

He did escalate the violence on March 19. As per his modus operandi, he targeted a big, fancy mansion, this one belonging to a cotton planter named Colonel J. H. Pope, who had two teenage servant girls, Clara and Christine, both of them Swedish immigrants. Like before, the unidentified attacker went behind the main house where the servants’ quarters were located, but this time he did something different – he came armed with a pistol. When he couldn’t break inside the room, he shot through the window, hitting Christine near her spinal column, but missing any vital organs. The noise brought out Pope and his men, so, once again, the predator had to scurry back to his burrow without a kill.

So far, the attacks had been ascribed to thieves on a rampage. Nothing certain was known about them other than the fact that they had to be Black. But this was just due to prejudice, not any kind of evidence. Despite multiple women surviving their encounters, none of them could say with any accuracy what their attacker looked like. Some said he was Black, but the German immigrant thought her assailant was white, while another woman thought that he could have been light-skinned, but that he painted his face coal black as a disguise.

Nor was there any certainty that he targeted Black women. Most of his murder victims would end up being Black, but not all of them. They wouldn’t even all be servant girls, despite his malicious moniker. Three of the women he attacked in March were white European immigrants, so it is more likely that the annihilator didn’t know or care what skin color his victims were. He just saw servant girls as convenient targets since they were unarmed, easy to overpower, and usually slept in remote quarters away from the main houses.

April was a quiet month in Austin. In late March, Chenneville and his men had arrested two Black men for separate, unrelated offenses, and, since the attacks on servant girls had stopped, they were hoping that they might have captured the culprit or culprits. However, the true Annihilator was just getting warmed up, and now it was time for his killing spree to begin in earnest.

The Killing Spree Resumes

On May 6, the Annihilator struck with the same kind of ferocity we saw in his first kill, targeting the home of Dr. Lucian Johnson or, more exactly, the little cabin in the backyard where his 31-year-old cook, Eliza Shelley, lived with her three young children. Like Mollie Smith, she had been the victim of an almost unbelievable level of violence. Not only was she hit in the head repeatedly with an axe, but she had also been cut and stabbed up and down her body, and had some sort of piercing metal implement like an iron rod impaled in her skull between her eyes. And to make matters worse, all of this had been done to her in front of her helpless children, who had been far too traumatized by their ordeal to be of any help to the investigators.

Once again, such malevolent and destructive barbarity was almost beyond the comprehension of local law enforcement. They desperately clung to their idea of the culprits being thieves who took things too far, but Dr. Johnson, a former state legislator, was the first to voice a fairly obvious concern: If this was, indeed, the work of thieves, why the hell would they target poor servants who barely had a dollar to their name instead of breaking into the main houses?

Still, that was their theory, and they were sticking to it. Bloody footprints revealed that the killer wasn’t wearing any shoes, so, with no other ideas, the police went out looking for the closest barefoot Black man they could find. They settled on 19-year-old Andrew Williams, described as a half-witted boy who once got arrested for stealing buttons. Fortunately for him, his feet were the wrong size, so the police had to let him go.

Two weeks later, the scenario repeated with different names. This time, the victim was 33-year-old Irene Cross, the Black cook of shoemaker Robert Weyermann. She had not been attacked with an axe, just with a knife, but her assailant cut so deep that her right arm had nearly been severed. Curiously, the Annihilator left her still alive, although it was pretty obvious that she was not long for this world. Miraculously, she stuck around enough to receive visits from the police and even reporters, but she could not do anything other than groan as she used up her last drops of life.

Austin went quiet again in June. The same goes for July. During that time, the city police were mostly preoccupied with arresting and beating Black men for minor offenses, hoping that one of them might spontaneously confess to a few gruesome murders just because they were caught stealing a chicken or something like that. But the people of Austin were not interested in methods; they were interested in results. For over two months, the city’s servant girls were free from attacks. Since not many people believed in the first place that all the killings were the work of the same sick and twisted individual, this must have meant that the police’s draconian techniques chased off the criminal element, who might have thought it prudent to relocate to another city. And, thus, Austin was safe again. That is…until the Annihilator committed his most heinous crime yet.

A Month of Terror

On August 30, 1885, the Annihilator visited the home of businessman Valentine Weed, just a block away from where he murdered Eliza Shelley. He found the servant quarters empty. Like many others, Weed’s maid, Rebecca Ramey, had taken to sleeping on pallets in the kitchen inside the main house, considering it a safer alternative than her own bed. But on that fateful night, this strategy offered little protection. For the first time, the Annihilator broke into the main house and entered the kitchen. He delivered a blow to Ramey’s head that knocked her unconscious. She was completely at his mercy, but then the Annihilator turned his attention to an even more alluring target – Rebecca’s 11-year-old daughter, Mary Ramey. The killer grabbed her, then dragged her outside to a washroom where he raped her, and then stabbed her in both ears with an iron rod. She was still alive by the time Weed had found her and called the doctor, but nothing could be done. The rod had pierced through her brain…twice. All she could do was make mumbling sounds as blood dripped out of her ears and nose with every breath. She died soon after.

This murder deviated from the others in two ways. It was the first time that the Annihilator went inside the house, and the first time he targeted a child. Was this a new way for him to inflict terror on the city of Austin, by showing them that nowhere is safe and that there is no depravity he wouldn’t sink to? Or was it done out of practicality? He had to go inside because many servants started sleeping in the kitchen, and he chose the smaller, weaker Mary Ramey because her mother was a fairly large woman who would have been hard to drag outside.

As before, the police of Austin had no interest in answering these questions. The era of profiling killers to understand their motives was still a century out. Most people still assumed this was the work of Black criminals, likely a gang, and wanted more officers to patrol Austin at night. Some locals even talked about forming vigilance committees to prowl through the city themselves, which, realistically, would have endangered lots of innocent Black men who would have been in the wrong place at the wrong time.

As for the real Annihilator, he did not seem intimidated by these propositions. If anything, they emboldened him, because his next attack was his most audacious. On the night of September 27, less than a month after the wicked murder of Mary Ramey, the killer broke into the servants’ quarters of the Dunham residence, where he found not one, not two, but four people. The Dunhams’ cook, Gracie Vance, normally lived there with her boyfriend, Orange Washington, but on that particular night, two other servant girls were staying with them, Patsy Gibson and Lucinda Boddy. The bitter irony is that the young women grouped themselves up for safety, but whether the Annihilator just picked them at random or specifically targeted them, to show that nobody could escape him, we cannot say.

Either way, as soon as he was inside the room, he got to work. Orange Washington was, obviously, the biggest threat, so he was the first target, receiving multiple fatal axe hits to make sure that he stayed down for good. The women were all incapacitated with swift hits to the head, and then the Annihilator picked the person who would feel the true extent of his sadistic wrath.

Gracie Vance was the unfortunate one. She was dragged outside into a bush near the stable, where she was first raped and then had her head crushed with a brick so viciously that the newspaper later reported that she was “almost beaten into a jelly.” Gibson and Boddy survived their encounter with the Annihilator, but Washington and Vance weren’t so lucky. It was the first time that the Midnight Assassin, as some papers took to calling him, killed two people in one night. But it would not be the last…

A Christmas Double

It had been another couple of months without any new attacks from the Annihilator. Despite this, every day, more and more servants packed up their bags and left the city, preferring to take their chances anywhere else. The mayor was finally forced to acknowledge the killings in public. Every newspaper in the state and quite a few national ones were covering the murders. The killer had made everyone so paranoid with fear that one elderly Black woman known as Aunt Tempy accidentally burned herself alive by sleeping with a burning oil lamp every night and setting the bed on fire. Maybe seeing the terror he had instilled in Austin was enough to keep him going, at least for a short while. Or maybe the Annihilator really did plan on leaving the city, but before he did, he had one final and bloody goodbye planned for Austin.

December 24, 1885 – ‘Twas the night before Christmas, when all through the house/Not a creature was stirring…” except for an extremely deranged and dangerous man armed with an axe. And he had paid a visit to the Hancock residence that night, but this time he didn’t target a servant girl. His victim was the lady of the house, 43-year-old Susan Hancock, who had been killed with two vicious axe blows to the head and a puncture with an iron rod to the ear. It won’t surprise you to discover that the city was far more outraged at the death of a wealthy, respectable white woman than all the previous servant girls put together, but their horror and fury would only grow because the Annihilator had another twofer planned for that night.

Just an hour later, while the police were still out with the bloodhounds, looking for the killer of Susan Hancock, they were alerted to another body, found lying on top of the woodpile of the Phillips household. It was Eula Phillips, widely regarded as one of the most stylish and most beautiful women in Austin. She had also been killed with several axe hits to the head, but the Annihilator did something new this time – he posed the body, placing her on top of the woodpile with her arms outstretched and three small pieces of wood on top of the stomach and breasts. Reporters at the time drew comparisons to a crucifixion.

These last two murders whipped Austin into a frenzy. The city was sitting on top of a powder keg with a lit fuse. Curfews were enforced. Vigilante groups were being formed. Some pressured the mayor to bring back the “lynch law,” which would have allowed vigilantes to do anything to suspects without consequences.

There was an attempt to pin the crimes on Walter Spencer, the partner of the first victim, Mollie Smith. The district attorney claimed there was enough evidence to suggest that Spencer killed Mollie, and if he killed her, then he probably killed some or all of the other victims, as well. But it soon became clear that there was no case here, just an unscrupulous DA looking for a scapegoat. In an unexpected, but pleasant move, the grand jury sided with the poor man getting railroaded and acquitted Spencer after just one day of testimonies.

Two other arrests occurred, and these were surprising, to say the least. In January 1886, both Jimmy Phillips and Moses Hancock, the husbands of the two dead white women, were charged with their murders. The idea was that they both killed their respective wives and pinned the blame on the Annihilator. Eula Phillips, in particular, was likely having an affair with a mystery man, and her husband was a violent drunk. Jimmy Phillips was actually found guilty and convicted of uxoricide, which is our word-of-the-day and means the killing of one’s wife. He was the only person convicted in the servant girl killings, but his conviction was later overturned, and Moses Hancock’s trial resulted in a hung jury, and neither one was ever tried again.

And the true identity of the Annihilator remains a mystery to this day. A popular theory points the finger at a Black cook with a violent temper named Nathan Elgin. One day in February 1886, a deputy tried to arrest Elgin while he was drunkenly beating up a woman. The cook resisted arrest and struck the deputy, at which point the latter pulled out his gun and shot Elgin dead.

Could this be why the Annihilator stopped killing? Or did he even truly stop? Some would say that the Annihilator simply packed up shop and traveled across the pond, beginning a new killing spree a few years later, in London’s Whitechapel. That’s right. There is a notion that’s been around for a long time that the Annihilator kept on killing in England, where he became known as Jack the Ripper.