For those of us who weren’t alive during the Cold War, it is difficult to understand the unique climate of fear and suspicion that seemed to pervade all of America in the first decade after the end of World War II in 1945. The Soviet Union had emerged from the war as a world power, seemingly ideologically opposed to everything the US and its allies stood for and just as determined to influence the course of world events. A conflict between them seemed inevitable, but when the USSR developed their first atomic bomb in 1949, it raised the terrifying possibility of a war between them leading to the complete destruction of civilization itself.

As a result, both sides turned to more covert means to gain an edge on each other, including espionage. When Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were arrested in 1950, accused of being the ringleaders of a Soviet spy ring in the US, it confirmed many Americans’ worst fears: that American citizens were so devoted to the philosophy of Communism that they would betray their country to do so. The response of the American justice system was swift and unmerciful: the couple was duly convicted of espionage in federal court, and three years later, they were executed for their crimes in the electric chair.

For many, that was the end of the story: they patted themselves on the back for a job well done, the country had been saved from the menace of Soviet spies. But as the years passed and the Red Scare died down, people began asking questions about the Rosenberg case. A review of documents pertaining to the investigation and trial revealed a litany of malfeasance, dirty dealing, and outright deception on the part of people who prosecuted and executed the Rosenbergs, leading to speculation that they had been framed. It certainly raised questions about whether they deserved to die for what they’d supposedly done: after all, they were the ONLY people in the entire Cold War period who were executed for espionage in the United States.

The tale of the Rosenbergs is a classic case of what can go wrong when people adopt the philosophy “the ends justify the means.” It is a story without heroes on either side: a potent mix of villains and victims, of idealism mixed with blatant self-interest. The end result was the destruction of an entire family, the orphaning of two small children, and a lot of questions about whether it is acceptable to deny civil rights to a group of American citizens because of their actions, or worse, simply because of their political beliefs.

Early Days

Both Ethel Greenglass, born in 1915, and Julius Rosenberg, born three years later, came from similar, unremarkable backgrounds. Both came from working-class Jewish families who immigrated to New York City from Eastern Europe to escape the crushing poverty and horrific anti-Semitism that were widespread at the time. Both were raised in New York’s Lower East Side, at the time one of the largest concentrations of Jews anywhere in the world. Both were clearly intelligent, and doing well in school. Julius studied electrical engineering at the City College of New York (CCNY), and Ethel would probably have done well at college as well, had she been allowed to attend (her mother Tessie believed that the only proper role for her daughter was to marry a Jewish man and bear his children). And both were politically active in left-wing causes in the 1930s, growing attached to the philosophy of Communism that the Soviet Union was espousing.

They were by no means the only people in America who were, mind you: the political philosophies of Marx and Lenin were popular among New York’s Jewish community, particularly those who were well educated, and it isn’t hard to see why: a utopian world where distinctions of social class, race and religious prejudices, and wealth inequality all vanished was an attractive one, particularly among those who had to overcome hardships like childhood poverty bigotry against Jews, and the massive reduction in jobs caused by the Great Depression. The draconian means by which Joseph Stalin was transforming his country into a socialist paradise was largely hidden from the outside world, allowing people to look at it through rose-colored glasses.

Julius and Ethel met in 1936 and quickly became inseparable. Their similar backgrounds, intellectual capabilities, and interest in left-wing politics complimented each other perfectly, and it didn’t take them long to fall deeply in love with each other. They wanted to get married almost immediately, but the Rosenbergs wanted their son to finish college first. Their wedding was held in June 1939, not long after Julius, known to friends and family as “Julie,” had received his diploma.

Julius took a job with the US Army Signal Corps in Fort Monmouth, New Jersey as an engineer, an essential occupation that exempted him from the draft when the US entered World War II in December 1941. From the outside, the Rosenbergs appeared to be a classic example of a successful American family. Julius had a good-paying job, while Ethel stayed home to look after the couple’s two sons: Michael born in 1943, and Robert, born in 1947. It was a peaceful life that wasn’t to last.

A Secret Double Life

In order to secure the job with the Signal Corps, Julius Rosenberg had to lie on the application, claiming to have never been a member of the Communist Party, which he was. Investigated and cleared in 1941 by the FBI, his past activities came back to haunt him in January 1945, when he was fired from the Signal Corps as a “potential security risk.” The US government didn’t know it at the time, but it was already too late.

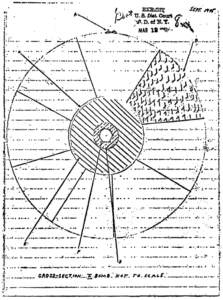

It has been established that Julius Rosenberg had been acting as a spy for the Soviet Union since at least 1942, passing on classified technical information from his workplace to his handlers, who were agents of the NKVD posing as Soviet diplomats. What’s more, he was actively recruiting others into his spy ring, including his wife’s brother, David Greenglass, a soldier who was stationed at Los Alamos, where the top secret project to develop the atomic bomb was being worked on. Greenglass was not an engineer, and so the information he delivered to his brother-in-law to pass on to his Soviet handlers was rudimentary at best since he didn’t understand the complex physics that went into the creation of the bomb. Other spies recruited by Julius included three college classmates of his: Morton Sobell, William Perl, and Joel Barr, all engineers who passed on information about the defense projects they were working on. Rosenberg hardly took any money from his Soviet contacts for his work, he was instead motivated by his sincere belief that advancing the cause of world socialism was the right thing to do.

After the war ended, the Rosenbergs struggled to make ends meet. There were no more government jobs on offer after Julius was fired by the Signal Corps, and when he went into business for himself with a machine shop, it quickly floundered. He also had no more classified information to pass on to the Soviets, so his spy ring also dried up. This must have been a double blow for Julius, no longer able to provide for his family OR to engage in the cause that had consumed his life. But at least he could take solace in the fact that he hadn’t been caught. But that too, wasn’t to last.

In the summer of 1949, the American government was alarmed to discover that the Soviets had detonated their first atomic bomb, years ahead of when they were expected to. For many, including FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, the only explanation for this premature end to America’s nuclear monopoly was that spies had passed on American nuclear secrets to the Soviets. But what started as a hunt for spies quickly descended into hysteria.

It All Falls Apart

Things began to unravel for the Rosenbergs in February 1950, when the German-born British scientist Klaus Fuchs was arrested by MI5. Fuchs was a physicist who had been intimately involved with the Manhattan Project, but he was also a Soviet spy who’d been passing on information on what he and his colleagues were working on throughout the war. He soon confessed as much to his interrogators, and the authorities on both sides of the Atlantic began a hunt to round up Fuch’s associates.

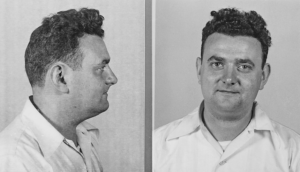

First to be arrested was Fuch’s courier, a man named Harry Gold. Gold, in turn, implicated David Greenglass as another spy who he collected information from. Greenglass was arrested in June 1950, and he too confessed to his involvement. There were also indications that David’s wife, Ruth, was also in the FBI’s crosshairs. After consulting with his lawyers and his family, David decided the best way to save himself and his wife was to help the FBI convict somebody else, namely his brother-in-law, Julius Rosenberg.

Julius was arrested in July, but unlike the others that had been implicated in the net so far, he refused to talk, refused to confess, or implicate others. The FBI searched around for anything they could leverage against Rosenberg to get him to cooperate, just as they had successfully done with David and Ruth Greenglass. When threats to impose the death penalty didn’t work, their next tactic was to threaten to prosecute Ethel Rosenberg, hoping that he’d cooperate to save his wife. But that didn’t work either, perhaps Julius knew as well as the FBI did that they had no evidence to charge Ethel with. Nevertheless, after testifying before a grand jury on two separate occasions in connection with her husband’s and brother’s cases, Ethel was arrested in August 1950.

To better explain (but not to justify) what happened next, it’s important to understand the geopolitical situation America found itself in at this point in time. The entire country was in a panic over the seemingly unstoppable march of communism all over the globe. The US and her allies had just ended a 15-month-long standoff with the Soviet Union over the fate of West Berlin, narrowly avoiding war. Mao Zedong had won the Chinese Civil War in October 1949, putting one of the largest nations in the world under a communist government. Mere weeks before the Rosenbergs were arrested, North Korea launched an invasion of its southern neighbor, triggering the Korean War.

And to top it all off, now the Soviets had “the bomb.” Any full-scale confrontation between the two superpowers, which many people believed to be inevitable, would now involve nuclear weapons, with all the wholesale destruction that came with it. The American public, whipped into a frenzy by reactionaries like FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover and Senator Joseph McCarthy, demanded strong action against communists both at home and abroad. The government was under enormous pressure to act, and the Rosenbergs came into their crosshairs at the exact wrong moment….for them, anyway.

Betrayal

The trial against Julius and Ethel Rosenberg began on March 6, 1951. The prosecution’s case rested on the testimony of David and Ruth Greenglass, who testified under oath that both Julius and Ethel were involved in espionage activities. This was a marked change from their earlier testimony when they said that only Julius had participated and that Ethel had not. Fifty years later, in 2001, David Greenglass would admit in an interview that he’d lied at the Rosenberg trial about Ethel’s involvement, that he’d been “persuaded” to change his testimony by the authorities in exchange for clemency for himself and his wife. “My wife was more important than my sister,” he said, also stating that he didn’t believe that they’d sentence her to death.

Julius and Ethel didn’t receive any support from the rest of the Greenglass family either, including from Ethel’s mother Tessie, who was quoted describing her own daughter as “a soldier of Stalin,” and that she had betrayed the United States their family so dearly loved. She did not have such harsh words for her son David, however, who was given a 15-year prison sentence for his role in the spy ring, being released in 1960.

The prosecutorial misconduct in the Rosenberg case went beyond merely encouraging the Greenglasses to betray their own family, however. The presiding judge, Irving Kaufman, had pulled several favors in order to be assigned to the trial, hoping to use the notoriety it garnered as a springboard to higher office: he made no secret of his desire to one day sit on the US Supreme Court. Meanwhile, chief prosecutor Irving Saypol’s deputy was 23-year-old Roy Cohn, an unscrupulous and ambitious character who was determined to win the case no matter the cost to further his own ambitions. According to Cohn, he had some private conversations with Judge Kaufman about the case throughout the trial, a highly unethical practice because the presiding judge is supposed to be impartial: that alone would have been grounds for a mistrial had it come out at the time.

With the deck stacked as it was, the Rosenbergs stood little chance of getting an acquittal. Their attorney, Emmanuel Bloch, was passionate, but he was a civil attorney who had little experience with criminal cases. He made a number of mistakes during the trial that later legal experts would point out may have contributed to the Rosenbergs’ conviction. Julius and Ethel didn’t help themselves during their testimony either, repeatedly pleading the Fifth Amendment against self-incrimination to avoid answering questions asked by the prosecutor: which even today makes people believe that the witness has something to hide and “must be guilty.”

The Rosenbergs were both convicted of all charges against them. When it came time to pronounce sentences on them, Judge Kaufman dropped the hammer. Declaring that their crimes had been “worse than murder,” Kaufman claimed that the Rosenbergs were to blame for the Korean War because of their delivery of the atomic bomb to the Soviets and that all the casualties that had been sustained were thus on their heads (an assertion that most people found ludicrous even at the time). He sentenced both of them to death in the electric chair, a harsher sentence than even J. Edgar Hoover wanted, particularly for Ethel: they wanted the Rosenbergs to name names, not to die. Hoover also worried that it would make the US government “look bad” to execute a young mother.

“Let Them Fry!”

For the next two years, Julius and Ethel sat on Sing Sing Prison’s Death Row while their appeals worked their way through legal channels. Manny Bloch and other attorneys pulled out all the stops to gain clemency for their clients, appealing all the way to the Supreme Court, and to Presidents Harry Truman and Dwight Eisenhower. But everywhere they turned, they were rebuffed: no one could find anything wrong with how the trial had taken place (the irregularities would not be exposed until much later) and no one wanted to go against the prevailing public opinion that the Rosenbergs should “fry.”

Overriding everything was a blinding fear of communism, which reached its zenith in the years after the Rosenbergs’ conviction in the Red Scare when thousands of people were harassed, investigated, prosecuted, or publically humiliated and fired from their jobs because of suspected communist sympathies. Roy Cohn was right in the middle of this effort, serving as Senator McCarthy’s right-hand man, trying to prove that communists had infiltrated every level of the US government to bring down the country from within.

All of this fear and panic shouted down the people who believed that the Rosenbergs had been railroaded, or that the sentence imposed on them was too harsh. Protests at embassies around the world and in front of the White House were ignored. On June 19th, 1953, first Julius, and then Ethel were led out of their cells and executed in Sing Sing’s electric chair. She was 37, and he was 35. More than 10,000 people turned out for their funeral in Brooklyn and burial in a Long Island Jewish cemetery.

The question remained what should become of the Rosenbergs’ two sons, Michael and Robert, who were 10 and 6 when their parents died. All of their relatives refused to take them in, claiming that they were ill-equipped to do so, but more likely trying to distance themselves from the infamy of raising two convicted spies’ children. The boys received hate mail from their foster home, with one letter writer demanding that they “change their names and become Christians,” hinting at an odious undercurrent of antisemitism that pervaded throughout the affair that American Jews were inherently disloyal. Eventually, the boys were adopted by the Meeropol family, and took their surname as a way to allow them to grow up out from under the shadow of the Rosenberg case.

Aftermath

The Rosenberg case has been controversial almost since the moment the trial was over. Many argued that the Rosenbergs had been innocent and were framed by their relatives and by the government. Others thought them guilty but believed the sentence was too harsh (the Rosenbergs were the only two people executed for espionage in America during the whole course of the Cold War). Michael and Robert Meeropol have been trying since the 1970s to exonerate their parents, and even as recently as September 2024 have petitioned the government for documents pertaining to the case.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the 1990s ushered in a period of retrospection about what the US had done during the previous four decades. In this light, the Rosenberg case has been re-evaluated. New information has come to light: decrypted Soviet diplomatic cables during World War II that were kept secret by the US government until 1995 show that Julius Rosenberg WAS a Soviet spy, passing on military and technical secrets, though as to the allegation that he was chiefly responsible for delivering the secrets of the atomic bomb to the Soviets, most historians find that incredulous: the material provided by Klaus Fuchs was far more damning than anything the Rosenberg spy ring offered up. In any case, his sentence for what he had done was far harsher than for other convicted spies: Aldrich Ames, a CIA analyst known as one of the most compromising Soviet spies in US history, received a life sentence for crimes considered much worse than what Julius Rosenberg had done.

The case of Ethel Rosenberg is particularly tragic: the same records that show Julius was a spy also show that Ethel was not an active participant in his activities and that the testimony from David and Ruth Greenglass that said she was had been a lie. Records of meetings from high-level Justice Department officials showed that they all knew the case against her was shaky at best, but they all felt they needed to put her on trial in order to pressure Julius into flipping for them. The problem was, Julius didn’t do what he was supposed to, and Ethel never made any appeals to save herself either, essentially calling the government’s bluff and daring them to actually execute them. Despite numerous appeals from her children and from others, Ethel’s conviction still remains on the books to this day, and it seems unlikely that’s going to change anytime soon.

Many of those who contributed to the death of the Rosenbergs met ignominious ends themselves: Irving Saypol died in 1977 under a cloud of suspicion involving allegations of bribery and corruption, while Roy Cohn, who has become one of the most infamous names in American history, died of AIDS in 1986, having been recently disbarred after one too many ethics violations. As for Judge Kaufman, he never made it onto the Supreme Court, and when he died in 1992, his long legal career was overshadowed by the cloud that came with sentencing the Rosenbergs to death.

Today, it is hard to imagine a case like the Rosenbergs playing out similarly in America: there are far more eyeballs on the operation of the justice system supposedly to prevent abuses from happening, after all. But the truth is, when faced with a supposedly existential threat, it is too easy to put aside the rule of law in order to keep the country “safe.” It is the same impulse that drove the US government to detain Japanese-Americans in internment camps during World War II and to detain suspected terrorists without trial in places like Guantanamo Bay and torture them for information in the wake of the 9/11 attacks. One can only hope that, if a similar instance crops up in the future, those in charge will remember the Rosenbergs, to prevent a similar miscarriage of justice from happening again.