In late 1859, a recruiting poster appeared on billboards and street posts throughout the American Western frontier. “Wanted,” it read. “Young, skinny, wiry fellows not over eighteen. Must be expert riders, willing to risk death daily. Orphans preferred. Wages $25 per week. Apply Pony Express Stables, St Joseph, Missouri.” With such encouragement, one of the most fabled and shortest-lived adventures of the American West sought riders to carry the mail on horseback in a series of relays that stretched from Missouri to California. The route crossed over 1,900 miles of mostly unsettled territory, much of it populated with indigenous tribes hostile to white men crossing what they viewed as their lands.

The Pony Express was born out of the need to improve communications with the state of California and the wealthy mine communities of the Nevada Territory in the months preceding the Civil War. At the time, a journey from New York to San Francisco via ship around Cape Horn took months, subject to the foibles of the weather. It could be shortened by disembarking along the Isthmus of Panama, crossing to the Pacific via steamship and wagon, and joining another ship near present-day Panama City. Such a journey was fraught with peril, not the least of which were yellow fever and malaria.

Another option for the journey was overland via stagecoach. Coaches ran on a more or less scheduled basis, usually connecting with towns located near Army posts. They were subject to attacks from bandits and Indians, and even if a traveler avoided those perils, the journey was slow, with weeks required to travel from St Joseph, in Missouri, to Sacramento, California. A third option was joining one of the wagon trains that slowly plodded westward along the well-worn trails. They too were slow, taking months to make the journey, if they made it at all. None of the available options were reliable, and none were suitable for rapid communication via mail and newspapers.

The Pony Express was a solution to that problem, though it was a short-lived one. It was in operation for just 18 months, and in that time it became a legend of the American West. The romantic image of a lone rider, facing and triumphing over the dangers posed by vast distances, inclement weather, hostile Indians, and roving bandits is part of Western mythology. In truth, it was a massive undertaking, a business that ultimately failed when it proved unprofitable. Still, it is part of American history as an attempt to overcome the imposing geography of the continent in the days before its settlement.

The Growing West

California was a little-known land of myth to most Americans when gold was discovered there in 1848. The Gold Rush triggered by that discovery led to a rapid expansion of its population from arriving gold seekers and other entrepreneurs and settlers. About half of these arrived in California by sea, disembarking in San Francisco, which became a boom town. From there, they traveled up the Sacramento River to the gold fields. The other half, more or less, traveled west via wagon trails which included the Oregon Trail to Fort Bridger in the Wyoming Territory, the Mormon Trail to Salt Lake City, and the route across the Nevada Territory, known by various names. Their terminus was also in the region of Sacramento.

The overland route established by the gold seekers, who became known to history as the 49ers from the peak year of the Gold Rush, was later used as the favored route by the Pony Express.

California became a state in 1850, part of the Compromise of 1850, as yet another attempt to stave off Civil War over the issue of slavery. The new state remained largely isolated because it was far distant from the eastern states. Yet over the ensuing decade, its importance to the nation grew. It was vastly rich, in far more than just gold. Due to the nature of its rapid settlement, it was populated with both pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions. Communication between California and the east grew more and more critical as the nation careened toward secession and war. Neither the telegraph nor the railroads had spanned the distance across the west. Towns and settlements located in the territories were isolated from both coasts, as well as each other. Military outposts dotted the territories and required shipping companies to supply them.

Creating the Pony Express

One such shipping company was the Russell, Majors, and Waddell firm, which serviced military outposts in the Wyoming and Colorado Territories. In 1859, its three principals, William Russell, Alexander Majors, and William Waddell formed a new concern, intended to carry mail and freight between California and the new settlements in the Rocky Mountains spurred by the discovery of gold near Pikes Peak. They named the new company the Central Overland California and Pikes Peak Express Company, which was known as the CCO & PP Express. The company also operated routes to outposts in the Wyoming Territory.

Although it carried mail, the service was necessarily slow, with mail waiting until full freight loads were ready, and then moving at a plodding pace. Which of the three partners first hit upon the idea of a fast-moving mail service is uncertain, but it was Russell who first mentioned one, in a letter dated January 27, 1860. Russell wrote, “Have determined to establish a Pony Express to Sacramento…”, adding his belief that such an endeavor could be in operation by April.

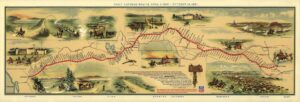

The three partners had considerable experience in organizing shipping routes, which also required way stations for fresh horses, as well as stables, reliable water supplies, feed, and drivers. Their first step in the new project was selecting the best possible route connecting St. Joseph, Missouri, where the railroad ended, and Sacramento. They divided the route between St. Joseph and Salt Lake City, which was fairly well-known, into three divisions; St Joseph to Fort Kearney in Nebraska; from there to Horseshoe Station, Wyoming Territory; and thence to Salt Lake City.

The route from Salt Lake City to Sacramento was then known only to explorers and hunters. The CCO & PP established two divisions along the route. In 1859, the three partners had begun building a road to haul freight between Sacramento and Salt Lake City across central Nevada. Throughout 1859, the company built the road and stations along it. There were two types of stations, way stations and home stations. The way stations were simply brief stops, where riders would change horses. They contained a residence for the station master and any employees, corrals, stables, and water and feed.

Home stations changed horses and riders, providing facilities for both. Riders completing their leg would rest at the home stations before beginning a leg in the opposite direction. Thus, riders remained within a portion of the same division during their service, becoming well-known to the stationmasters and their fellow riders.

The CCO & PP established the Pony Express as a separate, wholly-owned company in early 1860, with headquarters on Montgomery Street in San Francisco and in St. Joseph, Missouri. Branch offices were established in New York, Philadelphia, Washington, and other eastern cities. Mail delivered to the offices in the east was shipped by train to St. Joseph, where it was transferred to the riders. Mail heading eastward followed a reverse path.

To carry the mail, the company hired between 80 and 100 riders, but riders were far from the only personnel needed. Each of the nearly 200 stations required a station master to operate it. Corrals were needed for horses, and wranglers and stockkeepers were needed to man the corrals and stables. Stations required supplies, delivered by the CCO & PP’s wagons, which required drivers and loaders. Over 60,000 oxen and mules were purchased to haul the wagons. About 500 horses were purchased and distributed to stations along the route. By April 1860, when the Pony Express first opened, 186 stations were in place, averaging about 15 miles apart, with 80 riders ready to carry the mail.

The Riders

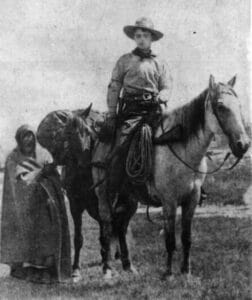

In addition to being young and wiry, the riders were required to swear an oath in which they promised to forsake liquor, profanity, and fighting, sworn before “…the Great and Living God.” Most of the riders were young and inexperienced, and many were indeed orphans or runaways claiming to be orphans.

Mark Twain personally observed the Pony Express in operation, and described the riders in his memoir Roughing It as “…a little bit of a man.” The riders were necessarily small, since the company mandated the combined weight of rider, saddle, accouterments, and mail would not exceed 165 pounds. The mail, carried in a specially designed leather pouch, weighed twenty pounds. Most riders carried nothing else beyond a pistol and a canteen. The weight restriction meant most riders weighed 125 pounds or less. Most were teenage boys, motivated by the relatively high pay for the day and the sense of adventure.

To earn that pay, which exceeded $100 per month at a time when the average laborer earned less than $20, riders covered an average of 75 miles per shift, changing horses at each way station. Since the riders simply “swung through” them, they were also called swing stations. They rode day and night, seven days per week. Like the riders, the horses were small, averaging just over 14 hands at the withers, roughly 4 feet 8 inches in height at the top of the front shoulder. Though most were not ponies in strictly technical terms, they were more or less pony-sized.

The saddles were specially designed, made with lightness and durability in mind. Covering the saddle was a device called a mochila, which was held in place over the saddle by the rider sitting on it. The saddle horn protruded from the front of the mochila, and the rear of the saddle, called the cantle, protruded from the back. The mochila draped over the sides of the saddle. Along the sides of the mochila were four containers of hard leather called cantinas, two in front and two in back, which carried the mail. When the rider arrived at a station he would dismount, grab the mochila, sling it over the saddle on a waiting horse tended by the stationmaster, mount, and continue on his way. If he was at the final stop for his leg, he gave the mochila to his relief rider.

Between stations, the riders did not proceed at a full gallop, as often depicted in film, unless they were being pursued or were badly behind schedule. The standard gait for each leg, which was between 10 and 15 miles, was a brisk trot. As the rider continued on the journey, the stationmaster tended to the newly arrived horse and ensured a horse was ready for another arriving rider in either direction. Since the express was a 24-hour-a-day operation, most stationmasters employed one or more assistants to aid them in their duties.

The riders were exposed to the ravages of the Paiute Indians during the Paiute War in Nevada, from May through July 1860. So were the station masters and other personnel. In fact, the Paiute War demonstrated that working at the stations was more dangerous than carrying the mail. Stations were raided for their valuable livestock, the stations themselves burned, and their occupants killed usually in gruesome ways as a warning to future trespassers. The Pony Express lost over $75,000 in property during the Paiute War, and at least 16 employees were killed, all but one station employee.

Only once was a rider killed by Indians in transit, but the Paiute had no use for the mail he carried and left it behind when they fled. The rider was 14-year-old Billy Tate. Tate’s body was found unscalped, an indication that he had earned the respect of the Paiutes who killed him. Two years later his mail pouch was discovered, and dutifully delivered to its destination, though by then the Pony Express had ceased to exist.

James Butler Hickok, known as Wild Bill, long claimed to have been a rider for the Pony Express. He wasn’t. Hickok, however, did at least work for the company, briefly, as a stockkeeper, meaning he managed a stable, feeding and watering livestock, and mucking out stalls. As such, it was a considerably less glamorous position than that of a rider. Buffalo Bill Cody greatly exaggerated his stories of being a rider for the Pony Express, as he did with many of his claims of achievements in the West. However, Cody did ride for the Pony Express, at the age of 15. Cody claimed one ride of 322 miles, which took over 21 continuous hours in the saddle, using 21 horses, which he called the longest ride in the history of the Pony Express. His claim is unsupported by company records but added to his considerable reputation.

Cody’s claim to have made the longest ride is also disputed by the reports of another rider, Jack Keetley. Keetley rode for the Pony Express for the entirety of its existence. Keetley is reported to have ridden some 340 miles in 30 hours, stopping only to change horses, having doubled back over his own route when a rider scheduled to travel in that direction failed to materialize. He was said to be asleep in the saddle when he arrived at his destination. Yet Keetley himself disputed that report, claiming his longest ride was “…said to be 300 miles and was done a few minutes inside of twenty-four hours.” Keetley claimed his ride took place between Fort Kearney and St. Joseph.

Although the topic is debated from time to time, company records do not support the feminist notion that some riders were female, disguised as boys.

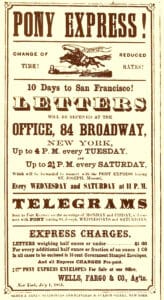

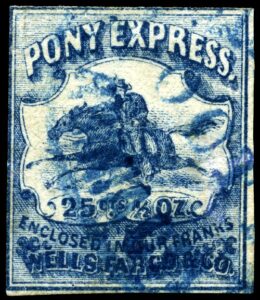

The Mail

The Pony Express offered speedy delivery, but it was expensive. Rates were based on weight. At the beginning of service in April 1860 a half-ounce letter cost five dollars, equivalent to roughly $175 in today’s money. By contrast, a letter weighing four times as much could be posted via the US Mail for two cents. The cost meant that the primary source of customers for the Pony Express were businesses. Business customers allowed the Pony Express to manage costs by providing its own lightweight paper and envelopes to customers, saving weight and thus saving costs, as well as making money by selling stationery.

According to the Smithsonian, the Pony Express, though it existed for just 18 months, went through four distinct rate periods. The first period, from April to July 1860, was the most expensive. That summer, the company attempted to reduce rates in the hope of increasing its customer base. The company began measuring weight by quarter ounce rather than half ounce, whereas before it had simply rounded up to the next half ounce. These rates remained in place until April 1861. That month, Wells Fargo and Company took over management of the routes and reduced rates to two dollars per half ounce, the third period. Finally, in July 1861, Wells Fargo reduced the rates to one dollar per ounce, which still greatly exceeded the rates charged by the US Post Office.

Because of the rates, the Pony Express was never popular for personal mail and remained mostly what would be considered a business courier service in modern parlance. Business communications and news, including stock market information, was a common source of mail for the express. Shippers could notify customers of shipping dates, as well as estimated dates of arrival. By June 1860, mail was routinely transiting between Sacramento and St. Joseph in nine or ten days, most of it business-oriented. From those cities, it continued on to its destination via the US Mail, telegraph, or private couriers.

The Pony Express lobbied hard to obtain a contract to carry US Mail along its route. Its failure to do so helped contribute to its early demise. Congress awarded the lucrative mail contract to the Overland Stage Route, in a series of deals involving bribes, kickbacks, and other extralegal machinations. The history of the American West is rife with corrupt contractual arrangements, bribes, and other such activities happily endorsed by some of the politicians of the day.

By late summer, 1860, the telegraph was encroaching upon the Pony Express. Fort Kearney, Nebraska was the westernmost telegraph station reachable from the east, while in the west the telegraph had reached Fort Churchill in the Nevada Territory. Efforts to connect the two outposts continued throughout the summer and autumn of 1860. Once connected, a faster means of communication would render the Pony Express, not yet one-year-old, obsolete.

The Election of 1860

The Presidential election of 1860 was the most consequential such event in American history. Several southern states had threatened to secede from the Union over the issue of slavery if the Republican candidate, Abraham Lincoln, succeeded in winning the Presidency. William Russell, one of the three principals in the Pony Express and its largest investor, wanted to use the election to emphasize the speed with which the service could disseminate the news to California and the western territories. He hired additional riders and positioned them at stations between Fort Kearney and Fort Churchill.

Lincoln was elected on November 6, 1860, though the victory wasn’t known until the early morning of November 7. It was immediately sent by telegraph to Fort Kearney. From there, word of Lincoln’s victory was carried by Pony Express riders to Fort Churchill, despite much of the trail across Nevada being covered in freshly fallen snow. From Fort Churchill, the news was telegraphed to Sacramento and San Francisco. Just under eight days after the Washington newspapers announced Lincoln’s victory, the news was reported in San Francisco, Virginia City, and other western cities still not connected directly to the east by telegraph. In the previous election, in 1856, just four years earlier, word of the results did not reach the West Coast until over two months had elapsed.

The election of 1860 was a clear indication of how the Pony Express had linked the nation, but it was also the beginning of the end. Southern states became clamoring for secession conventions, Missouri among them. In the end, Missouri did not secede but became a border state torn by factional strife for most of the Civil War.

The Ride Comes to an End

In March 1861, the Pony Express ceased operations between St. Joseph and Salt Lake City. Its stations and other infrastructure were taken over by stagecoach operations run by Benjamin Holladay, known in the West and among the congressmen he bribed as the Stagecoach King. With the new mail contracts, mail to Salt Lake City from the East was delivered by stage. The Pony Express continued to operate between Salt Lake City and Sacramento through the summer of 1862, carrying the US Mail. In October of that year, the telegraph finally connected Omaha, Nebraska with Sacramento, via Salt Lake City. Two days later, on October 26, 1862, the Pony Express ceased operations. Holladay quickly acquired its remaining assets. In the roughly 18 months of operation, the Pony Express had generated losses of $200,000, about $6.2 million today. It had simply been an unsustainable endeavor, its costs far outweighing its benefits to consumers, but it had been a romantic adventure for many.

Buffalo Bill Cody stressed that romanticism in his Western shows which became wildly popular in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, stressing, of course, his own involvement. Soon the Pony Express became a popular subject for dime novels, pulp magazines, and popular fiction. The film industry took up the mantle in the 1930s and 1940s, and as recently as 2012, with the documentary Spirit of the Pony Express. Television also celebrated the Pony Express including episodes of the long-running western Bonanza, and the 1989-92 series The Young Riders, which featured Stephen Baldwin as William Cody long before he was known as Buffalo Bill. It also featured Josh Brolin as Wild Bill Hickok.

Most of the route followed by the Pony Express is accessible today, with much of it controlled by the federal Bureau of Land Management. In 1992, Congress designated much of the route as a National Historic Trail. It passes through eight states, can be covered by automobile, and includes reconstructed stations as well as the ruins of some of the originals. Over four dozen such stations can be visited along the more than 1,800 miles of the route.

The western end of the original route is located at the Pony Express Terminal, at the BF Hastings Bank in Old Sacramento State Historic Park, Sacramento, California. The eastern terminus is at the Patee House Museum in St. Joseph, Missouri. When the Pony Express was running, the Patee House was a hotel, one of the largest in Missouri, and the site of the company’s eastern headquarters. The actual end of the ride for those arriving in St. Joseph was at the nearby Pike’s Peak Stables, named for the CCO & PP Express which operated it, and today is a museum dedicated to the Pony Express. The building was the site of the beginning of the first ride on the Pony Express on April 3, 1860.

Though the Pony Express failed as a business, for numerous reasons, it remains an important and remembered part of American history. It was one of several attempts to figuratively unite the sprawling country in the mid-19th century. Before it began operation, the idea of covering the distance between western Missouri and the California coast in just 10 days was considered madness. It achieved that goal on its first run, and continued to achieve it despite the obstacles for the short time it remained in business. Nothing surpassed its speed in delivering the mail over that distance until the opening of the Transcontinental Railroad in 1869.

Like much of the history of the American West, the Pony Express is shrouded in myth and romanticism. Most of its nearly 100 riders, its station masters, and the many hundreds of employees who made it work, even for just a short time, are forgotten to history. But the Pony Express lives on. In 2006, the United States Postal Service announced they had trademarked the name, Pony Express. Whether they intend to use it remains, to date, unknown.