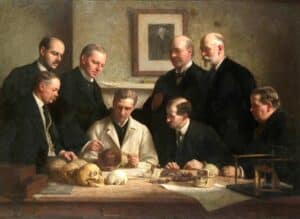

It was December 18, 1912, and a very exciting meeting was about to take place in London that would soon send the world into a frenzy. Before the Geological Society stood two men – amateur archaeologist Charles Dawson and paleontologist Arthur Smith Woodward, the Geology Department of the Museum of Natural History curator. The duo had something quite captivating to present to the scientific community – the reconstruction of a skull believed to have belonged to a human ancestor from 500,000 years ago.

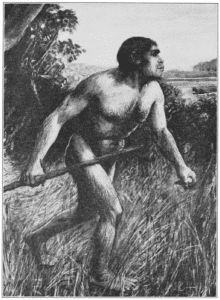

It was named Eoanthropus dawsoni after its discoverer, but most people referred to it by its other name – Piltdown Man. Soon enough, newspapers worldwide heralded it as the much sought-after “missing link” – an ancient ancestor whose existence had been theorized for decades, ever since Charles Darwin made evolution the hot topic of the natural sciences. The British media, in particular, was enthralled with the discovery and proudly labeled Piltdown Man as the “Earliest Englishman.”

Both the scientific community and the public at large accepted Piltdown Man as what they perceived it to be – a crucial discovery and a pivotal moment in the study of life on Earth. There was just one problem, though, and spoiler alert here – Piltdown Man was one of the greatest hoaxes the world had ever seen.

Discovery

On the morning of February 15, 1912, Arthur Woodward entered his office at the British Museum of Natural History where he found an intriguing letter at his desk. It was from an acquaintance named Charles Dawson, who was known in the profession as a skilled amateur fossil hunter. The letter mentioned various talking points such as discussing expenses for a dig the two had recently undertaken together and speculation over the new book Arthur Conan Doyle was working on, The Lost World. But it was near the end of the letter that Woodward’s interest peaked when Dawson informed him that he might have found an ancient human skull of great importance. He wrote: “I think portion of a human (?) skull which will rival H. heidelbergensis in solidity.” Heidelberg Man had been discovered in 1907 in Germany and created a big sensation and, clearly, Dawson hoped the same thing would happen with Piltdown Man in England.

A few months later, in May, Dawson paid a visit to Woodward in London and showed him his find – three different fragments of a skull which, even at first glance, appeared to show characteristics of both man and ape. According to Dawson, he obtained the first piece of the skull a few years earlier from some workers digging in the Piltdown gravel pit in East Sussex. Since then, he had spent his time searching for more fragments. After finding two more, he thought it was finally time to share his little project with others.

Woodward was intrigued. Although hearing bizarre claims from the general public came with the job, he had no reason to dismiss this one. Dawson, although he was a lawyer by trade, had a decent track record in paleontology. There was no doubt that the fossils he brought Woodward were unusual and the two had known each other for decades, so the museum curator didn’t suspect that any kind of skulduggery was afoot. It was settled – Woodward would travel with Dawson to Piltdown (specifically, at Barkham Manor) and they would dig together.

Once the necessary permissions were obtained, the two were off. They enlisted the help of a local laborer to do most of the grunt work, a chap named Hargreaves who was also known as Venus. As it turned out, they had another amateur paleontologist on hand to assist them – a French Jesuit priest by the name of Pierre Teilhard de Chardin.

On the very first day, the men found a small chunk of human skull bone and a tooth from a Stegodon. They kept coming back to dig every weekend, except for Teilhard who was busy with his clerical duties. Eventually, in June, their efforts were rewarded when they discovered a broken jaw, and then another piece of skull bone that joined up with the one they found on their first day. They recovered a few more skull fragments after that, enough for Woodward to begin work on the reconstruction of the ancient human head.

Despite their efforts to keep their digging hush-hush, word still got out. By the fall of 1912, there was this buzz in the British scientific community that Dawson and Woodward were doing some digging in East Sussex and that they were onto something big. Other scholars were already sending them letters of congratulations even though they still didn’t know what exactly they were congratulating them for.

On November 21, The Manchester Guardian published the first article covering the story. The discovery could be kept a secret no longer. Fortunately, by December, Woodward had finished reconstructing the skull. On the 2nd, he held a private showing for one of the country’s leading anthropologists, Arthur Keith, the director of the Hunterian Museum. After all, Woodward was an expert on ancient fish, not ancient humans, so this was the first time that a true specialist in the field set his sights on Piltdown Man. It seemed to pass muster. Keith wrote in his diary:

“The simian character of the lower jaw surprised neither of us; if Darwin’s theory was well founded, then a blend of man and ape was to be expected in the earliest forms of man. I was shown the reconstruction that had been made, giving Piltdown man the large canine teeth of an anthropoid ape. The hinder part of the skull, to my passing glance, seemed to be wrongly put together. I left the museum in no doubt that a discovery of the highest importance had been made in the unlikeliest of places – the Weald of Sussex.”

Keith’s diary entry listed multiple mistakes that he believed Woodward had made during the reconstruction, mistakes which Keith vigorously intended to pursue and expose. He later made no secret of the fact that he was incredibly jealous that someone else, someone who wasn’t even an anthropologist, had made the discovery of a lifetime that could completely rewrite human history, so he wanted to rain on Woodward’s parade a little bit if he could. But even so, Keith made no mention of suspecting a fraud and, given how he felt about the whole thing, he would have been the first to say it in every newspaper in the country.

The Big Reveal

Finally, the big moment had arrived. It was December 18 and most of London’s scientists had gathered at Burlington House in Picadilly to witness the unveiling of Piltdown Man. First to the stage was Dawson, who proceeded to tell the story of how the entire event unfolded, from finding the initial fossil to bringing in Woodward and, finally, to the moment they were all witnessing in person. He then went into some technical detail, explaining the various tests performed on the skull to determine the extent of the fossilization. Dawson asserted there was “no gelatine or other organic matter present. There is a large proportion of phosphates (originally present in the bone) and a considerable proportion of iron. Silica is absent.” This indicated that the fossilization process was almost complete, with no discernible traces of animal matter left.

Then came the big question – how old was it? Based on the depth of the earth in which the fossils were found and the presence of certain animal fragments found in the same gravel bed, Dawson estimated that Piltdown Man came “from the first half of the Pleistocene epoch.” According to the conventions of the day, this meant he was 500,000 years old if not one million.

This was like a mic drop in the room. Afterward, Dawson left and Woodward took to the stage before a stunned audience to give a technical presentation of the skull and its reconstruction. A third speaker, eminent neurologist Grafton Elliot Smith, gave a final lecture on the brain of Piltdown Man. Afterward, there came a period where the attendees were allowed to inspect the skull up close and have a chat among themselves. The night ended with some of the scientists offering their own opinions on the subject and already it had become evident that Piltdown Man would be a controversial topic.

There were two major talking points: the age of the fossils and the assembly of the skull. Nine men spoke up, all of them distinguished names in their field, be it anthropology, geology, anatomy, or paleontology. On the age of Piltdown Man, five thought that more data was needed to make the call; one gave no opinion, another agreed with Dawson’s estimation, and two believed that Piltdown Man was probably even older than that.

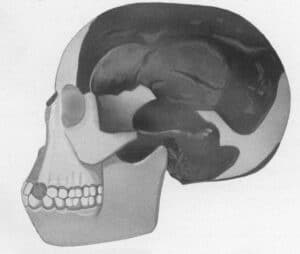

As it turned out, the reconstruction of the skull, not the age of Piltdown Man proved to be the more contentious point. Again, eight of the nine gave non-committal opinions, but one man – anatomist David Waterston – called shenanigans on the whole thing, as he stated that the jaw and cranium belonged to two different species. In Waterston’s view, the braincase “was human in practically all its essential characters” while the jaw “resembled in all its details the mandible of the chimpanzee.” He was certain that the skull of Piltdown Man was a composite and not the “missing link” that everyone was hoping for and reasserted his claim in a paper published in Nature the following year. But just like Keith, he made no accusations of forgery; merely human error.

Despite Waterston’s dissenting view, most of the audience left the conference room that night hopeful that they had been present for a major event in the history of mankind. Arthur Keith still proclaimed Piltdown Man to be “beyond doubt the most significant fossil discovery yet made in England, equal in importance to any fossil ever found in any country.”

Canine Chaos

With 1912 at an end, Piltdown Man was officially out in the open, exposed to the many accolades that hailed it as one of the greatest scientific finds in history, but also to the criticisms that questioned its accuracy.

The biggest challenge came, again, from Arthur Keith because, even though he constantly talked up the importance of the discovery, he was also convinced that Woodward screwed up the reconstruction. So he spent the first half of 1913 working on his own version of Piltdown Man which was more human in appearance and brain size. By mid-summer, word had reached Woodward of what Keith was doing and the two got into a bit of a feud over who was right and who was wrong. Only one way to settle this – Hell in a Cell; but that hadn’t been invented yet so, instead, they agreed to state their case before a panel of experts during the International Congress of Medicine in August.

On the day of the showdown, August 11, 1913, the London Times explained to its readers exactly what was at stake: “If Dr. Smith Woodward is right, we have to seek the beginnings of our modern culture and civilization at the middle of the Pleistocene period; if his opponent’s reconstruction is well founded, we have to go a whole geological period further back – perhaps a million years – to find the dawn of modern man and his culture.”

Around forty scientists, most of them from Continental Europe, arrived in London to attend the congress and judge the face-off between Woodward and Keith. They first traveled to the Natural History Museum, where Woodward held a two-hour presentation that was mostly an expanded version of the one he originally gave back in December. After that, the entire group piled into carriages and drove across town where Arthur Keith was waiting for them in the lecture room of the Royal College to give the presentation for his Piltdown Man, no longer called Eoanthropus dawsoni, but Homo piltdownensis.

The name alone indicated that Keith considered Piltdown Man a species of the genus Homo instead of its own genus as Woodward did so, from the outset, he clearly came in ready to lay the smackdown. So Keith proceeded, point by point, to identify all the mistakes that Woodward had made in his reconstruction and to show the panel of judges how it should have been done. One particular bone of contention was the canine – Woodward was convinced that Piltdown Man had a long, projecting ape-like canine, even though no such teeth had been found with the fossils. Keith, on the other hand, insisted that this was impossible because there simply would not be room for it.

Overall, it was clear that Keith had the better presentation and all that Woodward could do was sit there humiliated while his opponent verbally dismantled his work. Once it was said and done, Woodward had no choice but to make concessions, admitting that there might have been some errors in the original reconstruction. But he steadfastly refused to admit fault on the canines. He insisted they were correct which meant that Piltdown Man had the ape-like jaw that he envisioned which, in turn, meant that his original designation of Eoanthropus dawsoni was justified and should be upheld in favor of Keith’s Homo piltdownensis. To be honest, he came off like a desperate man clutching at straws…If only he could find that damned canine…

Piltdown 2: Paleo Boogaloo

Ask and you shall receive. While Woodward was defending his Piltdown Man from challenges from the scientific community, he and Dawson returned to the excavation site to do more digging. They were joined by Teilhard de Chardin, who didn’t stay long, but just long enough to mark the next major step in the Piltdown saga. Just a few weeks after Keith gave Woodward a metaphorical spanking in front of their colleagues, Teilhard de Chardin struck gold…well, enamel, but you get the idea. He had found the canine tooth.

Long and ape-like, it was everything that Woodward had hoped for and allowed him to put on his best “I told you so” face in September when he announced the discovery at a meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. He asserted that this find proved, without a doubt, that his original model was correct, barring only some minor adjustments, and that Arthur Keith was a liar, liar, pants on fire. Although he might not have used those exact words, we can’t be entirely sure.

Woodward certainly regained some credibility, but Keith refused to back down. The two spent the rest of the year and part of 1914 still going at each other, although this time they mostly did it in the pages of scientific journals instead of mano a mano. With each party convinced they were right, there was not much to do until another discovery was made. Fortunately, that didn’t take long.

In July 1913, Woodward and Dawson found something new at the dig site – a tool or a weapon made out of bone. Here’s the account straight from Woodward’s diary:

“…Searching the spot with my hands, pulled out a heavy blade of bone…It was much covered with very sticky yellow clay, and was so large as to excite our curiosity. We therefore washed it at once, and were surprised to find that the damaged end had been shaped by man and looked rather like the end of a cricket bat…

Mr. Dawson…soon pulled out the rest of the bone, which was still more surprising. This piece was also covered with sticky yellow clay but when we had washed it we found that it had been trimmed by sharp cuts to a wedge-shaped point.”

Later studies showed the bone to have come from the thigh of an extinct elephant species named Elephas meridionalis. It was considered, at the time, “by far the oldest undoubted work of man in bone.” So yet another accolade for Piltdown Man who had become the global rockstar of the paleontological world. For the first time ever, though, tiny whispers began spreading that Piltdown Man might have been a hoax. Up until now, even the critics only asserted that Woodward and Dawson were incorrect in their findings. Nobody claimed any deliberate attempts to trick or mislead. But now the possibility was raised, although not in any scientific journals; it was more like gossip and innuendo.

However, mere hearsay and tittle-tattle were not enough to derail the popularity of Piltdown Man. It had become way too big and, at that point, Woodward didn’t have to bother defending his ancient buddy. Other scholars did it for him and they all quickly shut down the idea of a hoax. American geologist William Gregory wrote in the American Museum Journal that there was no doubting the genuineness of the discovery or the character of the men involved. British biologist Ray Lankester proclaimed Piltdown Man to be the “missing link” and heralded the discovery of his jaw as “the most startling and significant fossil bone that has ever been brought to light.”

And, believe it or not, it was about to get even bigger because, in January 1915, Dawson wrote Woodward to tell him that he had unearthed something incredible at a new site – a second Piltdown Man. This time, he had found “a fragment of the left side of a frontal bone with a portion of the orbit and root of the nose.”

Dawson was playing coy this time, refusing to disclose the exact location of the dig, even to Woodward. All the latter knew was that it was a few miles away from the original site, somewhere around Sheffield Park. Then, six months later, Dawson wrote again, this time informing his colleague that he had uncovered a molar tooth belonging to their primitive friend. Things were heating up again as Woodward was preparing to unveil Piltdown II to the world and soak up more accolades. And then…Charles Dawson died suddenly of septicemia in August 1916, at 52 years of age.

The scientific world mourned the loss of a giant. Woodward had a more personal reason to lament the death of his colleague – he had no idea where Dawson dug up the fossils. He delayed the presentation of Piltdown II as he tried to find the site on his own, but with no luck. Eventually, he gave a brief speech at the Geological Society in London on February 28, 1917. This presentation was much more subdued than the first one. For starters, Woodward didn’t have much to say and only a few bone fragments to show. And there was still a somber atmosphere due to Dawson’s recent passing, so only a few speakers rose to say a few things and they were all understated and agreeable.

Piltdown II didn’t have the impact that Woodward had wanted, but at least now almost everyone was inclined to accept his Eoanthropus dawsoni as an ancient ancestor of man. He had cemented his name in the history books…At least, for a while…

Fraud Exposed

We told you at the start of that Piltdown Man was a hoax, so you knew this was coming. However, it took its time to get here. Basically, whatever suspicions and criticisms people might have had weren’t enough. They had to wait for technology to catch up and reach a point where it could conclusively prove that Piltdown Man was nothing but grade-A humbuggery.

It certainly was suspicious that after Dawson’s death, not another single fragment of the archaic man was ever found. And it wasn’t for lack of trying because Woodward lived for almost another three decades and he kept on looking in vain for something that was never really there in the first place.

More suspicions were raised during the 1920s and 30s when the fossils of other prehistoric men started being found in Asia and Africa and, although they shared similarities between them, not so much with Piltdown Man. But it wasn’t until 1949 that geologist Kenneth Oakley exposed the Piltdown fossils as fake with a new dating method that used fluorine. According to his test, the bones were only 50,000 years old, a far cry from the 500,000 to one million that people previously asserted.

This was a heavy blow for Piltdown Man, but it still could have been a simple mistake, not necessarily a forgery. But Oakley wasn’t finished. He then teamed up with anthropologist Joseph Weiner and anatomist Wilfrid Le Gros Clark to deliver the knockout punch. In 1953, they published a paper that showed that not only was Piltdown Man much younger than originally thought, but it was a composite like Waterston asserted decades earlier. The skull was human and it had been boiled and stained to give it the right color. The jaw, however, belonged to an orangutan whose teeth had been filed down to give them a human-like wear pattern. Now there could be no doubt – somebody faked the whole thing. Once word got out, the London Star proclaimed Piltdown Man to be “the biggest scientific hoax of the century.”

To be honest…pretty impressive. Anything that becomes the “biggest blank in blank” deserves some props, right? But who should get those kudos? Just because people proved Piltdown Man was fake didn’t mean they also knew who did it.

The suspect list included people like Arthur Conan Doyle at one point, but only four names had some significant merit. One of them you haven’t heard – Martin Hinton. He was a volunteer at Woodward’s museum and was later found to have stained fossils in his collection. He hated his boss so it’s possible he planted some bones out of a desire to embarrass or frame Woodward, but there’s no way he was responsible for the main fossils. Then there was Woodward himself, of course, and Teilhard de Chardin. Both discovered some of the fossils and benefited from it, especially Woodward. However, the French priest was out of the country for many of the finds, and if it was Woodward, he probably wouldn’t have spent the second half of his life looking for bones he knew were not there.

But come on…let’s be honest – it was Charles Dawson. It had to be him. He had the knowledge and opportunity to pull it off. Plus, remember, he was the only one who knew about the location of Piltdown II since, you know, he chose it, and that the finds stopped once he died. Recent tests on both Piltdown fossils showed that they had been stained and modified using the same technique. According to the testers, paleoanthropologist Isabelle De Groote:

“The science showed us these hominin specimens are all connected. They carry the signature of a single forger…There is only one person associated with the finds at Piltdown II, one man with means, motive, and opportunity to commit the infamous hoax: Charles Dawson…I think we can show with a very high degree of certainty that he possessed the orangutan jawbone that created the fakes at both sites. It’s got to be him.”