Officially, they were the 1st Demolition Section of the Regimental Headquarters Company, 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division. But the world soon knew them under a different name – the Filthy Thirteen, the biggest troublemakers in the United States Army.

Their story became famous two decades after the war, in 1967, when The Dirty Dozen was released in cinemas. The movie, itself based on a novel written two years earlier by E. M. Nathanson, told the tale of a group of military convicts who were sent on a suicide mission deep into enemy territory to blow up a chateau full of German officers before D-Day. The book was already a bestseller, but the film became an even bigger hit, and today it is regarded as one of the quintessential war movies.

When Nathanson wrote his novel, he had heard the story of the Filthy Thirteen, supposedly from his friend, producer Russ Meyer, who worked as a combat photographer during the war. But the version he knew came strictly from word-of-mouth, and, despite years of research, he could not corroborate what had really happened and ended up writing a mostly fictionalized account. Suffice it to say that things worked out for him in the end, but today we’re going to try to set the record straight and present the true story of the real Filthy Thirteen.

Who Were They?

Okay, let’s get some of the biggest differences out of the way to avoid confusion. Unlike their movie counterparts, the Filthy Thirteen were not criminals. They were just a group of ragtag troublemakers who knew that they were too valuable to be punished too severely regardless of what they did. Plus, they knew many of them were likely to die in combat anyway so it’s not like the army could threaten them with anything. What would their officers say? “Behave yourselves or you don’t get to go on this suicide mission?”

Here is what the group’s unofficial leader Jake McNiece aka “McNasty” had to say about the types of shenanigans they got up to:

“We never took care of our barracks or any other thing, or sanitation, and we were always restricted to camp…But we went AWOL every weekend that we wanted to and we stayed as long as we wanted till we returned back because we knew they needed us badly for combat. And it would just be a few days in the brig. We stole jeeps. We stole trains. We blew up barracks. We blew down trees. We stole the colonel’s whiskey and things like that.”

It’s not very surprising that the group was labeled “arguably among the most difficult, insubordinate, and undisciplined individuals in the U.S. Army while in garrison. From today’s perspective, McNiece and his gang of delinquents were out of control and lacked the discipline ingrained, required, and expected of individuals belonging to the profession of arms.”

As for the “Filthy Thirteen” designation, we’re not sure who came up with it originally, but it caught on after reporter Tom Hoge used it in an article for Stars and Stripes in the June 1944 issue. Supposedly, the gang of miscreants earned this moniker while training in England because they refused to bathe or shave, instead preferring to use their daily water rations to cook wild game which they poached from a nearby manor house.

But while “filthy” they may have been, “thirteen” they were not. At least not for long. Counting alternates and substitutes, over two dozen men were part of the group at various points throughout the war. But ultimately, what truly mattered was that they were heroes…albeit unwashed and undisciplined heroes. When the chips were down, they fought bravely, risked their lives and, in some cases, even sacrificed them in battle.

Like many other paratroopers, the members of the Filthy Thirteen first received their training at the Jump School at Fort Benning in Georgia. After that, those who qualified were sent on to Camp Mackall in North Carolina where they were officially assigned to the 101st Airborne Division and continued their training. Then it was off to Fort Bragg and, from there, the entire regiment was shipped to England on September 5, 1943, aboard the SS Samaria.

That is where the Filthy Thirteen formed in earnest. Originally, it was just McNiece and a couple of other troublemakers like Maw Darnell, Max Majewski, and Louis Lipp aka LouLip, but once they began gaining a certain unwholesome reputation, other sergeants started dumping their problem soldiers in that unit and, before you knew it, the Filthy Thirteen had assembled. Men with colorful names such as Jack “Hawkeye” Womer, George “Googoo” Radeka, Robert “Ragsman” Cone, Roland “Frenchy” Baribeau, Johnnie Hale better known as Peepnuts, and William Green aka Picadilly Willy. Then there were also Joe Oleskiewicz, Jack Agnew, and Chuck Plauda, but they didn’t get cool nicknames. And while they had several section leaders while in England, the one who led them into D-Day was Second Lieutenant Charles Mellen who was one of the few officers who got along okay with the rambunctious unit.

On June 5, 1944, allied forces everywhere were gearing up for the invasion of Normandy. All the training and the planning were over and now it was time for action. The soldiers knew that many of them would not be coming back home, but McNiece came up with a way to boost the morale of his unit by embracing his Choctaw heritage – he shaved everyone’s head into a mohawk and applied war paint on their faces. The image of the men donning mohawks and warpaint became iconic after being featured in Stars and Stripes, thus cementing the legacy of the Filthy Thirteen as the most rebellious unit in the war.

Douve Bridge on D-Day

On D-Day, the entire 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment was tasked with securing the Douve River, ideally by blowing up all the bridges below the canal and seizing control of the main one. The plan, however, quickly went pear-shaped and the paratroopers sustained heavy casualties. The Germans expected this airborne assault and had created a grid over the landing zone by crisscrossing cables from telephone poles to catch the incoming parachutes and gliders, just like flies in a spider’s net. The paratroopers unfortunate enough to get stuck in the nets became easy targets for the Nazi soldiers below.

The plane carrying the Thirteen got shot up to hell before they could jump. That sounds bad…and, yes, it wasn’t ideal, but it did mean that the aircraft went off-course, so when the paratroopers finally jumped, they avoided the nets. When they landed, they were about eight miles from the bridges they were supposed to blow up.

Already, some of the men were missing in action and others had been killed, including the section leader Lieutenant Mellen. McNiece landed on his own in an open field and started making his way towards his destination, hoping to run into a few friendly faces and avoid the German patrols.

Initial signs were not encouraging. The first person he came across was LouLip, who had broken his back during the fall and could not move. He kept moaning “baseball and Bill Lee” over and over again, which was what they had been taught to yell when jumping instead of “Geronimo.”

After about two hours of dodging and fighting German soldiers, McNiece started to run into other American troopers. There were about ten of them by the time they unexpectedly stumbled unto a German headquarters, opening fire and killing everyone inside.

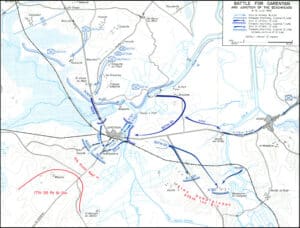

About three in the morning, the group reached the Douve Canal. Their mission was to blow up the two smaller, wooden bridges, and to hold the main bridge that led to Carentan, if possible. They were only supposed to blow up that one if the Germans began crossing it with tanks, to prevent them from sending reinforcements to the beachhead. The squad had about 15 men at this point and most of them were either demolition or mortar men, so rigging up the explosives wasn’t difficult. By daybreak, they had finished, but then came the hard part – holding the line.

It wasn’t long after they had finished setting up the explosives that the Germans opened fire on them from the other side of the canal. They tried crossing it with infantry once, but the Americans gunned them down to the very last man and neither side tried crossing it again. Instead, the Germans relied on mortar and sniper fire to keep them at bay. One particularly nasty sniper managed to kill four or five of the American soldiers before Jack Agnew took him out.

The fight went on like this for days. Stragglers from other paratrooper units kept showing up to bolster the American ranks, so that by the third day, there were around 50 of them fighting to hold the bridge. Meanwhile, McNiece and his gang had no idea what was happening with the war outside the canal, but they found out on the fourth day when four P-51 Mustangs flew overhead and blew up the bridge.

Basically, what had happened was that the American command had no idea they had a group of surviving soldiers fighting to hold the bridge. Instead, they had given the bombers orders that, after hitting their primary target, to expend all remaining ammunition on secondary targets…which the bridge happened to be.

On one hand, this was good because it meant the Allies were pushing the Germans back. On the other hand, it also meant that McNiece and the rest fought for nothing for three days. And it was about to get a lot worse because the Mustangs didn’t know they had Americans below them. They just thought they were all enemy soldiers…so they opened fire on them. According to McNiece’s estimate, fifteen of their own men were killed by friendly fire before the Mustangs flew back home.

After that fiasco, the question for the survivors was what to do now. They didn’t have any other orders. Hell, the high command didn’t even know they were there. Eventually, they figured that, since the Allies had captured the beachheads, they would be pushing retreating German troops towards them, so they hunkered down and prepared for another fight, this time on the opposite side.

They were right. On the afternoon of the fifth day, a German battalion reached them. Although heavily outnumbered, the Americans had time to get into a good position and waited until the enemy soldiers got trapped between two ditches before opening fire, turning the canal into an absolute bloodbath.

Fortunately for McNiece, the Americans chasing the Germans towards them recognized that they were dealing with friendlies and didn’t open fire on them this time. After five days of guarding the Douve Bridge, what was left of the Filthy Thirteen plus the other paratroopers were relieved of their duty and made their way to regimental headquarters.

Operation Market Garden

They got some well-deserved rest plus some decent food courtesy of the local French villagers who, according to McNiece, made the best soup he’d ever tasted in his life. He even got to enjoy a thick, juicy steak since so many cattle had been killed by gunfire and artillery, but after that, it was time to head once more into the breach.

There weren’t enough paratroopers left to form their own unit, so the survivors of the Douve Bridge now joined the Regimental Headquarters Company. They were sent right back to Carentan to help take the town, which they did after a couple of days of fighting.

After that, finally, there was a bit of downtime where the paratroopers were given fresh new clothes and shiny medals and sent on a seven-day pass to England. This allowed McNiece to take stock of what had happened to his men since he had no idea at the time. He and Jack Agnew were the only two of the original Filthy Thirteen who fought to hold the bridge. He knew that their section leader, Lieutenant Mellen, had been killed during the jump, but he also found out that Peepnuts, Googoo Radeka, and Frenchy Baribeau were also dead, while Ragsman Cone and Maw Darnell had been taken prisoners. He met again with Jack Womer, Oleskiewicz, Majewski, and Chuck Plauda when he rejoined his company.

Majewski had been reassigned to staff, so it was only McNiece, Agnew, and the other three left out of the original Filthy Thirteen, which meant they needed another eight replacements to fill their ranks. We’re not going to give you all the names, we’ll just mention John Dewey and William Coad, for now, since they would stick around for a while.

Once the squad was full again, it was back into the fray, this time as a part of Operation Market Garden, a plan by Allied forces to invade Nazi-occupied Netherlands in September 1944. This was a two-pronged attack – first, American and British airborne units were to take control of several key bridges over the Nederrijn, followed by a land invasion over said bridges.

The Filthy Thirteen, as part of the 101st Airborne Division, jumped into Eindhoven. It was September 17, on a Sunday afternoon. Even before the jump, they were one man down. Chuck Plauda’s parachute was defective, so he had to return to England and that was the last time that the others saw him during the war.

The entire 101st landed within a square-mile area about ten miles north of Eindhoven. The jump certainly went smoother than D-Day, but the division was surrounded by tanks in every direction. Even though the Allies had taken extensive reconnaissance photos of the area, some of the top brass were convinced that the tanks were fakes, inflatable props put there to deter such an attack. The Allies did this sort of thing, too, most notably a United States deception unit known as the Ghost Army – stay tuned for a bio on them in the near future. These tanks, unfortunately, were the real McCoy, and the 101st immediately found itself embroiled in a bitter fight for survival. Here’s how McNiece tells it:

“We landed in a square-mile area and man, there were tanks thirty yards in any direction we looked. In fact, they were so stinking thick in there that they really could not maneuver. They were fully armed and went to work on us. We immediately went to work on them. It took us probably two hours to clean out that whole area. It was pretty rough. We lost a lot of people to those tanks but we got organized after we knocked all of them out…The 101st was really very, very lucky to come out of that fight.”

That initial dust-up was bad, but things went smoother from then on. Once the division was in the city, they went from house to house to clear them but didn’t encounter much German resistance. Instead, they mostly ran into grateful Dutch people who greeted them with a chunk of cheese, black bread, or a glass of gin. The main bridge over the Wilhelmina Canal had been rigged with charges to explode, but they were unmanned so the demolition boys had no trouble dismantling the explosives and securing it. In just 36 hours, Eindhoven was under Allied control.

On the third day, the land forces entered the city. Most of the 101st joined them as they kept marching on the highways and pushing back the enemy, but McNiece and his demolition platoon were left behind to guard the bridges in Eindhoven. Unfortunately for them, the Germans had a little bombing run in mind for them, and they sent four Messerschmitts to attack the bridges that same night. They managed to destroy one bridge and kill two sergeants, leaving McNiece as the only section sergeant in the platoon.

The Filthy Thirteen stayed in Eindhoven for five days total before getting the word to move on up and join the rest of the division. They were caught in an ambush in Veghel and engaged in another brutal fight with the Germans in the city streets that lasted for several days and got a lot of the demolition boys killed, including another original member of the Filthy Thirteen, Joe Oleskiewicz.

In total, the demo unit spent 78 days in the Netherlands during Operation Market Garden and the fight in Veghel was the worst of the lot. After that, they mostly did guard duty and line repair. But just to end things on a lighter note, let’s recall one of the funnier moments of the campaign involving two of the new Filthy Thirteen recruits, Dick Graham and Dinty Mohr. One day, shortly after Veghel, Graham got shot in the butt. McNiece ordered Dinty to use his trench knife and dig it out but Mohr, being a “big ole stout country boy,” reckoned he could just push it out with his finger…which he did.

Dick got patched up and was fine after that, but clearly that kind of experience stuck with him. When the three of them met up again 50 years after the war, Dinty jokingly kept pointing his finger at Graham, causing the latter to exclaim:

“If you point that finger at me you lousy rat, I will break your arm clear off of you!”

The Pathfinders

The Filthy Thirteen might have had it pretty rough so far but it was about to get a lot worse in the Pathfinders. Ostensibly, during World War II, Pathfinders were special Airborne units that jumped shortly before the main body to deploy navigation aids for the drop zones. Although, in reality, as McNiece put it: “the purpose of pathfinding service was to jump anywhere at any time for any plausible causes.”

With an 80 percent mortality rate, it was one of the deadliest jobs in the world. In fact, it was so dangerous that the top brass were not allowed to assign men to the Pathfinders. Only paratroopers who volunteered for it were accepted.

And McNiece volunteered…sort of. He did it thinking that he wouldn’t have to do any actual jumps. He figured the war was nearing its end and the Allies had total aerial supremacy, so he would spend what was left of it at Chalgrove Air Force Base near Oxford where the pathfinding headquarters and training area were located. No more slop and meager rations. Instead, he would dine on fancy Air Force food and make quick trips to Oxford for all the women and the whiskey he wanted. Plus, he could stay there for some postgraduate work after the war. In his mind, after the hell he went through, McNiece was signing up for paradise.

To his credit, McNiece refused to encourage any of his Filthy Thirteen brethren to join him, just in case things didn’t work out as he figured, but four of them did it anyway: Max Majewski, Jack Agnew, William Coad, and John Dewey. A lieutenant named Williams also joined them, so that night the six of them packed their bags and headed for England.

At first, things looked like what McNiece had hoped. He even got promoted to acting first sergeant and all the boys received three-day passes to London. Unfortunately for the Pathfinders and the Allies, in general, the Germans had one last major push in them – a surprise attack in the Forest of Ardennes, known as the Battle of the Bulge. Just ten days after arriving in England, on December 23, 1944, the Pathfinders were getting ready to jump.

McNiece had a team of 20 men and they were tasked with a resupply mission to Bastogne where Allied soldiers were trapped by Germans on all sides. He thought he would need a miracle to make it through this one, but somehow he got it – out of 20, there was only one casualty. The others landed safely, found shelter, and deployed something called CRN-4 sets, which were beacons that sent signals with their exact position to resupply airplanes. Within the hour, C-47s were littering the skies with airdrops. McNiece and his men stayed on those sets for five days, guiding over 600 deliveries of ammo, gas, and equipment. Most of that time was spent in the basement of an old house alongside two Belgian women, a teenage boy, and a dozen chickens. They only ate three. Chickens, we mean, not Belgians, but the women used the bones, some potatoes, and some green vegetables to make, according to McNiece, the best soup he had ever eaten…again. Better than the French villagers, apparently, or maybe McNiece just really, really liked soup.

After seven days of fighting, the Armored Division arrived and drove the Germans back after they had failed to take Bastogne. That was it. The Pathfinders had succeeded in their mission and each received two bronze stars back in England for their efforts.

And that was about it for the Filthy Thirteen. After that, the ones in the Pathfinders were returned to their old demolition unit, but the cleanup duty they did in Germany and Austria was just a casual stroll through the park compared to the missions they already had in their back pocket. And then the war ended and McNiece and the rest of the Filthy Thirteen went back home to their old lives, with only memories of the time they spent as one of the most unruly gangs of GIs ever assembled in United States military history.