Manifest Destiny – a term coined in 1845 which endorsed the idea that God destined the United States to expand its dominion and spread its values of capitalism and democracy from the Atlantic to the Pacific. This triggered a massive westward migration, as scores of pioneers left the safe and familiar surroundings of the Eastern United States to stake their claim on a piece of land out west. And, of course, the California Gold Rush spurred things on significantly.

Just a year later, in 1846, 87 American settlers went into the Sierra Nevada mountains, looking to cross them and make their way to California. Only 48 made it out alive. Trapped in the snow with not enough food and supplies, many of the settlers perished, falling victim to disease, starvation, and freezing temperatures. Others decided that they were willing to do anything to survive. To ward off the grim specter of death, they engaged in the ultimate taboo – cannibalism.

A Plan Takes Shape

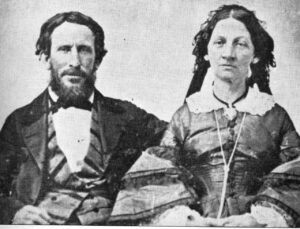

In 1845, an Irish immigrant named James Frazier Reed grew discontent with his life in Springfield, Illinois. Born in 1800 in County Armagh, Reed came to America as a young boy alongside his widowed mother. As an adult, he worked hard and steadily grew his fortunes, so that by the time he was in his mid-40s, he was a successful businessman with a large family and a prosperous farm.

He was also pretty bored in Springfield. Most other people would have been over the moon if they had everything Reed had, but for him, life simply lacked that certain something that gave it pizzazz. But Reed knew where he would find it – California.

Long-distance migrations were all the rage in America back then. First, there was the Great Migration of 1843, when a thousand pioneers hitched up their wagons and left Missouri to settle in the Oregon Territory. Then there was also the Mormon migration, which saw the Mormons flee from the Midwest to escape persecution and find a new home in the Salt Lake Valley, in Utah. And last, but certainly not least, there was the Gold Rush, which prompted scores of “miners forty-niners” to make their way down “Californee way” in the hopes of striking it rich.

James Reed intended to be one of these settlers who ventured into the dangerous unknown, looking for fame and fortune. But he had a tough task ahead of him. Back then, those who wanted to reach the Pacific Coast had two basic ways of getting there and neither one was particularly enjoyable nor fast. The first was by sea. But this was before the Panama Canal was built, so those who attempted this journey had a long voyage ahead of them, as they had to round Cape Horn, the southern tip of South America, and then sail back up north.

The other option was by land but, again, this was before the transcontinental railroad, so travelers had to resort to overland trails through the treacherous, mountainous regions of the American frontier. The Oregon Trail was the preferred route for this method of transport. It was well-traveled, but, as its name suggested, it took you to Oregon. There was also the California Trail, but this one was still being developed and pioneers had not found the optimal route yet.

But James Reed was not concerned with such minor details. You see, he heard of a guy named Lansford Hastings, an early pioneer who traveled to Oregon and California in 1842 and then wrote the book The Emigrants’ Guide to Oregon and California. He presented the Hastings Cutoff, a “shortcut” that supposedly shortened the trip by 300 miles and had it join the California Trail towards the end so that travelers finished their journey in Northern California instead of Oregon.

There was just one problem, though – Hastings was talking out of his ass. Not only was his cutoff longer than the regular, more established trail, but it went through rough mountain terrain and the Great Salt Lake Desert. Hastings had never done that route when he wrote about it. Nobody had. He traveled only a portion of it, on horseback, with other men who were traveling light. He didn’t have a full wagon train in tow with women and children. If such a caravan were to attempt to cross the Hastings Cutoff, it would be a guaranteed recipe for disaster.

Westward Ho!

Despite the perils and uncertainties, James Reed had found a pair of like-minded individuals who wanted to make the trip with him – brothers George and Jacob Donner. Like Reed, they were prosperous farmers, so what exactly possessed them to pack up their whole families and march through the untamed wilderness we’ll never know. They were also significantly older than the middle-aged Reed. George Donner was 60, his brother was 56, and, of course, both of them had large families, mainly consisting of children under ten.

And so, on April 14, 1846, the Donner-Reed Party left Springfield, Illinois. The initial group numbered 31 people and consisted of James Reed, George and Jacob Donner, their entire families, plus a dozen or so employees and teamsters (which were animal drivers). They made their way to Independence, Missouri, nicknamed the “Queen City of the Trails” because it was the departure point for many of the trails to the Pacific Coast. In early May, the party reached the city, but they were already cutting it pretty close. You might think that they had all the time in the world since it was still spring, but travelers on these trails were on a pretty tight schedule to ensure that the pack animals found plenty of grass to eat on the way.

That’s why late April was the standard cutoff for starting these trips. Fortunately for the Donner-Reeds, they arrived in time to join the last wagon train of the season. It would be a close shave, but good conditions should get them to California in four months. Of course, as we all know by now, the journey they were about to undertake was anything but good conditions.

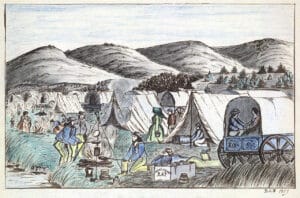

To be fair, the first part of the voyage was pleasant and easy-going. Everyone was left awestruck by the many wonderments of nature that they encountered daily, and the nights were filled with singing, dancing, games, “and the kindliest feeling (of) good-fellowship.”

There were around 50 wagons in the party, although suffice it to say that none of them were quite like “Reed wagons” which James Reed had custom-built. Clearly, he spared no expense, as evidenced by the description provided by Reed’s stepdaughter Virginia. She wrote:

“Our wagons, or the Reed wagons as they were called, were all made to order and I can say without fear of contradiction that nothing like our family wagon ever started across the plains. It was what might be called a two-story wagon or Pioneer palace car, attached to a regular immigrant train…The entrance was on the side, like that of an old-fashioned stagecoach, and one stepped into a small room, as it were, in the center of the wagon. At the right and left were spring seats with comfortable high backs, where one could sit as on the seats of a Concord coach. In this little room was placed a tiny sheet-iron stove, whose pipe, running through the top of the wagon, was prevented by a circle of tin from setting fire to the canvas cover. A board about a foot wide extended over the wheels on either side the full length of the wagon, thus forming the foundation for a large and roomy second story in which were placed our beds. Under the spring seats were compartments in which were stored many articles useful for the journey.”

Although they sounded fancy, not everyone was a fan of the “Reed wagons.” In fact, the other people resented them for two reasons. One – they were quite show-offish, as if James Reed was constantly saying “Look at me! I’m richer than you!” And two – they were heavy and slowed down the whole wagon train. They needed an extra pair of oxen to pull them, and this was on relatively even ground. Just imagine how much of a burden they would become if they had to travel over rough, mountainous terrain. But don’t worry. They probably won’t have to do that…Probably.

Mild inconveniences aside, the first six weeks of the trip went smoothly and the group managed to traverse 650 miles of country, crossing most of what’s now southeastern Wyoming until they reached Fort Laramie. This leg of the journey was the same regardless of whether you intended to take the Oregon Trail, the California Trail, or some crazy, new experimental trail that was supposed to be the best of the bunch. But eventually, they reached the crossroads and it was decision time: did they stay on the well-traveled path and follow the Oregon Trail to Fort Hall in modern-day Idaho? Or did they take the unknown Hastings Cutoff and supposedly shave a few hundred miles off their route, while also ending up in northern California? They chose…poorly.

A Fatal Mistake

On July 20, most of the wagon train went on its merry way to Fort Hall, leaving behind the members of the ill-fated Donner Party. Their numbers had swelled well past the original 31 who left Springfield, Illinois. The party now included 87 people who were convinced by Reed and the Donners that they knew what they were doing. We’re obviously not going to mention everyone. We’ll just say that notable additions included the Graves family, the Breens, the Murphys, the Kesebergs, the Eddys, the McCutchens, and a few bachelor men who either traveled alone or tagged along with the aforementioned families.

They elected George Donner as their leader, which is why the group is remembered as the Donner Party. Reed might have been the driving force behind the trip, but it seems that people simply didn’t like him that much. They found him too ostentatious and autocratic compared to the more calm and more peaceful Donner.

Anyway, their first stop was Fort Bridger, a trading post that represented not only the beginning of the Hastings Cutoff, but also the party’s last chance to restock on supplies before coming out on the other side. This was the moment that the group truly became doomed. Unbeknownst to Reed or any of the other travelers, a journalist named Edwin Bryant had already scouted Hastings’ shortcut on horseback and concluded that it was a terrible route that should not be undertaken in wagons under any circumstances. He even wrote back to warn everyone, but nobody in the Donner Party ever saw the letters. Reed later accused Bridger and his partner, Vasques, of withholding the letters on purpose, to get them to go through with the trip. If the Hastings Cutoff were to become the new standard route for settlers headed to California, that would have meant a lot of extra business for their trading post.

On July 31, the party set off on their fateful journey through the Hastings Cutoff, heading towards the southern end of the Great Salt Lake. After only a few days, it became apparent that this new route was not all it was cracked up to be, but the group pressed on. At least, until they reached the Wasatch Mountains. Up until this point, Reed had acted as a guide, following directions carved into trees by none other than Lansford Hastings himself, the guy who got them into this mess in the first place. Initially, Hastings promised to join the group, but he hooked up with a different party at Fort Bridger and left a few weeks ahead of the Donner-Reed group. That faction was known as the Harlan-Young Party, and the reason you’ve never heard of them was that they actually arrived at their destination, albeit sick from thirst and exhaustion.

Although this is speculation, it wouldn’t be outlandish to suggest that Hastings might have been using these groups as guinea pigs, trying to discover the best route through his eponymous shortcut. Because even though he had found a viable route through the mountains with the Harlan-Young Party, he left instructions for Reed to travel a different way with his group, promising him that it was the better solution.

It wasn’t, you’ll be surprised to hear. The Donner Party traveled at a snail’s pace, covering less than two miles a day, and this while all the healthy men in the group worked ‘round the clock to clear the road of debris for the wagons. On August 25, the party had its first casualty – 25-year-old merchant Luke Halloran. Halloran was one of the bachelors who joined the trip and, realistically, there were slim chances of him ever making it to California since he was suffering from consumption, or tuberculosis, as we call it nowadays.

It took the Donner Party 18 days to travel 30 miles, but in late August they were out of the mountains and, finally, had nothing but smooth sailing until they reached their destination. Just kidding! They now had to cross the Great Salt Lake Desert, one of the most inhospitable areas in the United States, devoid of drinking water or grass to feed the animals. Oh, and as an added bonus, the ground was moist and brittle, making it very easy for the wagon wheels to sink into the salt crust.

It was just happy days all around for everyone involved. But, at least, by this point, everyone realized that they had been sold a bum steer with the Hastings Cutoff. But don’t worry, things were about to get worse.

The Trail of Death

On September 26, 1846, the Donner Party reached the Humboldt River, completing the crossing of the Hastings Cutoff. No other people died during the ordeal, but they lost dozens of animals and were forced to leave many wagons behind. At this point, they rejoined the traditional California Trail, but the situation was far from sunshine and rainbows. They were a month behind schedule and the Donner Party was now trapped in a race against time, needing to cross the Sierra Nevada before the weather turned sour.

Tensions were hot and they boiled over on October 5, when a fight broke out between James Reed and a teamster of the Graves family, John Snyder. Everyone had different opinions on who started it and why, but the result was the same – Reed plunged his knife into Snyder’s chest, killing him in minutes. There was some discussion of hanging Reed right then & there but, eventually, the group decided to banish him, letting him fend for himself. Reed agreed to his punishment as long as they continued to take care of his family.

At this point, we can firmly say that the Donner Party had disintegrated. They weren’t one cohesive unit anymore, just a bunch of people who happened to share the same misfortune. Their survival instincts kicked in, so they splintered off into smaller groups, looking out only for themselves and to hell with everyone else.

Case in point: On October 8, Lewis Keseberg kicked an older Belgian companion named Hardkoop out of his wagon, telling him he needed to either walk or die. None of the others wanted to take him, so the old man fell behind the group and was never seen again. A few days later, another man named Wolfinger was killed ostensibly by Paiute Native Americans, who regularly raided the party for their livestock, although he might have been murdered by two of his traveling companions. And then a week after that, a member of the Murphy family, William Pike, was shot and killed in an accident. That’s four deaths in less than a month and before the group even entered the Sierra Nevada.

It was becoming increasingly clear that many of them were not going to make it to California. But just when things were at their bleakest, a tiny speck of hope pierced through the dark shroud. It was Charles Stanton, one of the men who rode ahead of the group in search of help. He had reached Sutter’s Fort and had returned with seven pack-mules loaded with food, as well as two Miwok helpers named Luis and Salvador. This gave everyone enough confidence that maybe, just maybe, they could make one last push and cross the mountains before getting snowed in.

A Frightful Feast

Initially, snowfall wasn’t expected until the middle of November, but hey – everything else had gone to the dogs, why would this be any different? The snow came in early, and when the group reached Truckee Lake, they encountered a blocked pass that had been completely snowed in. They had no choice – they had to winter in the mountains. Both the pass and the lake were later renamed after Donner to commemorate the fact that half the party never made it out of there alive.

Around 60 people camped by Donner Lake, taking advantage of some rundown cabins that had been built there by earlier travelers. The remaining 20 or so, consisting of the Donner families and their helpers, had to make camp further down the trail, by Alder Creek, because the axle on their wagon broke.

By December, food supplies were almost exhausted. People began dying of malnutrition, while others survived by boiling oxhide and horse bones. Every now and then, catching a mouse or some other small rodent represented a veritable feast. William Eddy was briefly the hero of the camp when he hunted a bear, but even that was quickly devoured until there was nothing left.

Something needed to be done, or else everyone would starve to death by springtime. In mid-December, a group was formed. They were called the Snowshoe Party because they improvised some snowshoes out of oxbows and hides, but historians later bestowed upon this group the more appropriate name “Forlorn Hope.” It consisted of 17 of the most resilient people in the camp – men, women, even a few children. They were going to try to make it over the pass on foot and get help.

It was a desperate plan, but one that was destined for failure. Nobody in the group had the strength, experience, or supplies to make such a journey. They got lost in the snow and after two days with no food, a man named Patrick Dolan was the first to say it – they needed to eat someone otherwise they would all die. The question was – who?

They talked about drawing lots to see who would be the unlucky sacrifice, or maybe about having a duel. Eventually, they reasoned that one of them would drop dead of natural causes soon enough, and they would not have to kill anybody. And it was true. A teamster named Antonio died not long after that, followed by the Graves family patriarch, Franklin Graves, but a blizzard forced the others to leave their bodies behind. Then Patrick Dolan died after running naked into the snow, delirious from hypothermia. And then the youngest of the group, 13-year-old Lemuel Murphy, also perished. The survivors held out as long as they could, but after five days of starvation they were mad with hunger, more animal than human. And so they crossed that line that most people would find inconceivable and ate Patrick Dolan, averting their gaze from one another as they cut off strips of his flesh and roasted them on the fire.

The two Miwok guides, Luis and Salvador, were the only ones who refused to partake. Oddly enough, this turned them into targets that could be killed for food. After all, even in the deepest reaches of despair, racism was alive and well, so the group reasoned that, if push came to shove, it was better to kill two Native Americans than two whites. William Eddy was the only one not ok with this, so he warned Luis and Salvador and told them to run away. They did, but without any food, they didn’t make it very far. A few days later, the Snowshoe Party, which now consisted only of two men and five women, came upon the Miwok guides, still alive, but hanging on only by a thread. One of the two surviving men, William Foster, killed both of them. Now, the group weren’t just cannibals, they were murderers…

Relief & Rescue

Their actions, heinous and gruesome as they may be, worked, and on January 19, what was left of the Snowshoe Party reached the Johnson ranch in the Sacramento Valley. After regaining his strength, William Eddy continued to Sutter’s Fort, where he informed everyone of their plight. He discovered that James Reed had also made it out of the mountains and attempted to organize his own rescue, but both men encountered the same problem. In another example of spectacular timing, in April 1846, right after the Donner Party left Illinois, the Mexican-American War had started and California back then was still a part of Mexico. The colonel at Sutter’s Fort needed all his soldiers and it wasn’t until February that he could spare a few men to launch a rescue operation.

And, of course, that wasn’t all. It was still winter and Donner Lake was snowed in so rescuers couldn’t use any wagons. Instead, they had to hike and climb, bringing only whatever supplies they could carry. And they couldn’t take back everyone so they would have to do it in stages.

The first relief team, consisting of seven men led by William Eddy, reached the camp on February 18. They found at least a dozen dead and most survivors were in a state of shock or delirium. There was evidence of cannibalism here, as well, although the survivors gave conflicting accounts over who ate who. Same thing at the Donner camp near Alder Creek. It seemed that the Donners suffered the most losses out of everyone: both Donner brothers died, as did their wives and a few of their children. The only adult who made it out of there alive was a teamster named Noah Jones. The relief team took 23 people with them, leaving food for the others to be rescued later. Even so, they weren’t out of the woods yet. Some of the evacuees died en route, and other campers perished while still waiting to be rescued. It wasn’t until April and three additional relief teams later that all the survivors were extricated from their camp of death.

The last rescue party found only one person still living – Lewis Keseberg, allegedly surrounded by human parts in a sight “too dreadful to put on record.” Even though the previous team left him plenty of food, he was suspected of murdering Tamsen Donner and not just eating, but also robbing her. And although many, if not all the survivors ate human flesh, the newspapers turned Keseberg into the true villain of the story. But just like the rest of the Donner Party, he faced no legal consequences for his actions, and lived out the rest of his days as a free man, albeit one with the reputation of a killer cannibal.

So, 89 people went into those mountains…48 people come out, the snow and the famine took the rest, December 1846. Anyway, we delivered the bio.