In 1996, the FBI apprehended a man that alluded capture for nearly two decades. His homemade letter bombs struck fear across the country — mostly targeting airlines and universities — earning him the nickname, “Unabomber.” All told, he killed three people and injured 23 more. He took great care not to leave a trace of evidence and unlike other serial murderers, he didn’t seek glory and fame for his killings. If it wasn’t for his “Manifesto,” the publication that outlined his disdain of technology and modern society, he may have never been caught.

After his arrest, the world was shocked this backwoods hermit, living without electricity or running water, could be the man responsible for such sophisticated killings. Today we explore the man, domestic terrorist and “lone wolf” killer, Ted Kaczynski.

Early Life

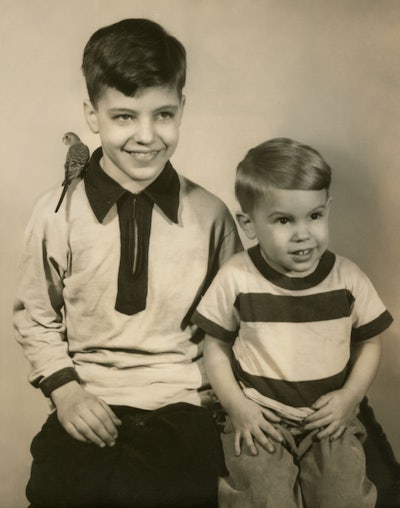

On May 22, 1942, Theodore John Kaczynski was born in Chicago to blue-collar, second-generation Polish Americans, Theodore “Turk” and Wanda Kaczynski. Seven years later the Kacynski’s had a second son, David.

Little is written about Ted’s early years except for one incident that may have been the impetus to the boy’s tendency to alienate himself (according to his mother and brother). When Ted was a nine-month-old baby he developed a severe case of hives that required him to be quarantined for ten days in the hospital. Afterwards, Wanda reported it took a long time for son to return to his normal, happy self. Worried about his shyness and social development, Wanda claimed she considered putting her young son into studies for autistic children but ultimately decided against it. At least one neighbor remembered him as “strictly a loner.”

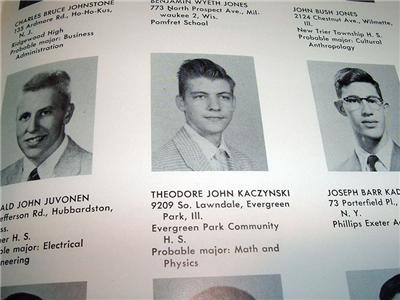

When Ted was ten years old the Kaczynski family moved out of Chicago to the southwest suburb of Evergreen Park — at the time a neighborhood predominantly made up of Irish, Italians, Czechs, and Poles. Ted’s parents would later say the move out of Chicago was so the boys could enjoy a better class of friends.

At Evergreen Park, Ted thrived and seemed like a normal kid to most people with one exception — his remarkable intellect. In the fifth grade, Ted was labeled a genius after he scored 167 on an I.Q. test. His high marks put him in the same I.Q. range as theoretical physicists Stephen Hawkings and Albert Einstein. Ted skipped sixth grade and then at the urging of school administrators, his junior year of high school.

Ted would later claim his parents pushed him too hard and being younger and smaller than his classmates made it difficult for him to fit in with his peers. Still, he had some friends and was the “ringleader” of an outcast cliche known as “the briefcase boys” at Evergreen Park Community High School. Ted was especially adept in mathematics and science and spent hours working out advanced problems. In high school he joined the chess, biology, German and mathematics clubs. He played trombone in the marching band, explored the music of Bach and Vivaldi, and wrote compositions for himself, his younger brother David, and their father to perform at home. His physics teacher Robert Rippey, described him as “honest, ethical, and sociable.”

Ted attended summer school and was able to graduate at the age of 15. That year, he was one of five National Merit Finalists at his high school. One former classmate said Ted was, “never really seen as a person, as an individual personality … He was always regarded as a walking brain, so to speak.” Ted seemed aware of how others viewed him. He later said, “By the time I left high school, I was definitely regarded as a freak by a large segment of the student body” and he felt, “a gradual increasing amount of hostility” from the other kids.

In 1958, Ted was accepted into Harvard. As part of the recommendation letter, his high school counselor Lois Skillen wrote:

“I believe Ted has one of the greatest contributions to make to society. He is reflective, sensitive, and deeply conscious of his responsibilities to society. … His only drawback is a tendency to be rather quiet in his original meetings with people, but most adults on our staff, and many people in the community who are mature find him easy to talk to, and very challenging intellectually. He has a number of friends among high school students, and seems to influence them to think more seriously.”

During this period of his life Ted held immense promise for his future but he may not have been ready to leave home. One friend remembers urging Kaczynski’s father not to let the boy go, arguing, “He’s too young, too immature, and Harvard too impersonal.”

Harvard

As an incoming Harvard freshman, Kaczyniski was 16 years old. The health-service doctor who interviewed him as part of the routine screening process noted, “Good impression created. Attractive, mature for age, relaxed. … Talks easily, fluently and pleasantly. … likes people and gets on well with them.”

Being among the youngest and brightest freshman, Ted was housed at 8 Prescott Street, a three-story Victorian house just outside Harvard Yard. That year, the dean of freshman Skiddy von Stade Jr. decided to use the residence specifically for less-mature boys who needed a more intimate, nurturing environment. It was a place where these boys would not get lost in the larger, impersonal dorms. Some have come to the conclusion that while the dean’s plan was well-intentioned, putting all the fragile young men together had the opposite effect. It isolated them, making adjusting to Harvard more difficult. One student living at 8 Prescott said later, “It was not unusual to spend all one’s time in one’s room and then rush out the door to library or class.”

After his arrest, Kaczynski’s housemate Gerald Burns wrote that he “was as normal as I am now: it was [just] harder on him because he was much younger than his classmates.” Despite the adversity, he took up swimming and wrestling, played trombone and pick-up basketball. He had a few friends.

Kaczyniski’s sophomore year marked the beginning of — in his words — “the worst experience of my life.” Together with 21 other undergraduate students, Kaczyniski was a participant in an unethical study conducted by Henry A. Murray, the Harvard professor and psychologist best known for pioneering personality tests. Before Harvard, Murray had been a colonel in the U.S. Army and an agent for the Office of Strategic Services (OSS; what later became the CIA) during World War II. According to his colleagues at OSS, Murray was obsessed with mind-control and used LSD, among other drugs, to determine how to brainwash subjects. There is no evidence to suggest Murray used LSD on his experiments with Kaczyniski.

The study was officially named “Multiform Assessments of Personality Development Among Gifted College Men” and its purpose was to measure how the students reacted under stress. Subjects were told they would be debating personal philosophies with other students and to write essays detailing their beliefs and aspirations. The essays were then turned over to anonymous attorneys who conducted “vehement, sweeping, and personally abusive” interrogations. The participants wore electrodes to monitor their physiological response and the sessions were filmed. Later, subjects’ expressions of rage during the interrogations were repeatedly played back to them. Some sources have suggested that Murray’s study was part of the federal government’s research on mind-control known as Project MKUltra. Author Alton Chase questioned whether the “purposely brutalizing psychological experiment” contributed to the making of Kaczyniski, the “Unabomber.” However, by no means can Kaczyniski’s bombing campaign can be, “laid at Harvard’s door” though his staunch, anti-technological views are recognized, in part, to Harvard’s curriculum in the late 1950s.

Kaczyniski earned his Bachelor of Arts from Harvard in 1962, finishing with a 3.12 GPA. In his own words, Ted later recalled his experience overall at Harvard as “a tremendous thing for me.” He thrived on the hard work and self-discipline and “became enthusiastic about will power.”

Mathematics Career

Kaczyniski enrolled at the University of Michigan In 1962 at the age of 20 and spent the next five years of his life in Ann Arbor. He earned his master’s degree in 1964 and his doctoral degree in 1967. Michigan was not his first choice school — he would have preferred the University of California at Berkeley or the University of Chicago. He was accepted to all three but Michigan offered Kaczyniski a teaching position and financial aid package. At Michigan, Ted received $2,310 annually, roughly the equivalent of $19,000 today. During his time there he specialized in geometric function theory and completed his dissertation Boundary Functions to great acclaim. His doctoral advisor Allen Shields called it the “best I have ever directed,” winning the Sumner Byron Myers Prize for Michigan’s best mathematics dissertation of the year. Kaczyniski published five journal articles based it — two while at Michigan and three after.

Despite Kaczyniski’s academic success (he earned 12 As, and 5 Bs over 18 courses) and his student’s rating him an above-average instructor, he didn’t enjoy Michigan. He thought the standards were wretched and the professors were mostly “sloppy, careless, and poorly organized.” And he said,“…most instructors and most students did only what they had to do — there was no interest or enthusiasm or even any sense of responsibility about doing a good job.”

The mathematics department was enthusiastic about him but many others didn’t seem to notice him. Underneath the quiet and studious demeanor, no one suspected his rage was building, his ideology was forming, and he made the conscious decision to start killing. Kaczyniski later said, “I thought ‘I will kill, but I will make at least some effort to avoid detection, so that I can kill again.”

According to Sally Johnson who conducted a psychological profile on Kaczyniski during his court proceedings, it was during his fourth year at Michigan that he began to fantasize about breaking away from society. She wrote, “he decided that he would do what he always wanted to do, to go to Canada to take off in the woods with a rifle and try to live off the country. ‘If it doesn’t work and if I can get back to civilization before I starve then I will come back here and kill someone I hate.’” Kaczyniski also shared with Johnson that he suffered from nightmares and sexual repression during this time. He began fantasizing about being female and reasoned the only way he would ever be able to touch a woman was to become one. Kaczyniski went so far as to make an appointment with the university’s health center to discuss a possible sex change but he had a sudden change of heart in the waiting room. He shared with Johnson his feelings of humiliation and disgust, and then suddenly felt better when he thought about murdering the psychiatrist. “Just then there came a major turning point in his life,” he later told Johnson. “Like a phoenix, I burst from the ashes of my despair to a glorious new hope.”

In late 1967, Kaczyniski became the youngest assistant professor of mathematics in the history of U.C. Berkeley. He was 25 years old. He stayed on for less than two years teaching undergraduate classes in geometry and calculus before a “sudden and unexpected” resignation. No one knew at the time that Kaczyniski never intended to launch his career at Berkeley. He only wanted to earn enough money to fulfill his plan of checking out of the modern world and into the wilderness. By the mid- to late-1960s Kaczyniski had concluded mathematics was too close to the evils of technology which he despised. In 1971, Kaczynski wrote an essay, it began, “it is argued that continued scientific and technical progress will inevitably result in the extinction of individual liberty.” It was imperative that this juggernaut be stopped, Kaczynski went on. This could not be done by simply “popularizing a certain libertarian philosophy” unless “that philosophy is accompanied by a program of concrete action.”

Montana

After leaving Berkeley, Kaczyniski lived with his parents for two years before building his remote cabin outside of Lincoln, Montana on land he purchased with his brother’s help. The cabin was a simple structure with no electricity or running water. At first, he survived by working odd jobs; using an old bicycle to get to and from the town. He taught himself survival skills such as tracking game and edible plant identification and organic farming. He visited the library and read classic works in their original languages.

In 1975, he started to see the impact of real estate development on the Montana wilderness and it enraged him. He had considered living peacefully but now all he wanted was to “get back” at the system by acts of revenge and carry out his earlier fantasies of killing.

Bombings

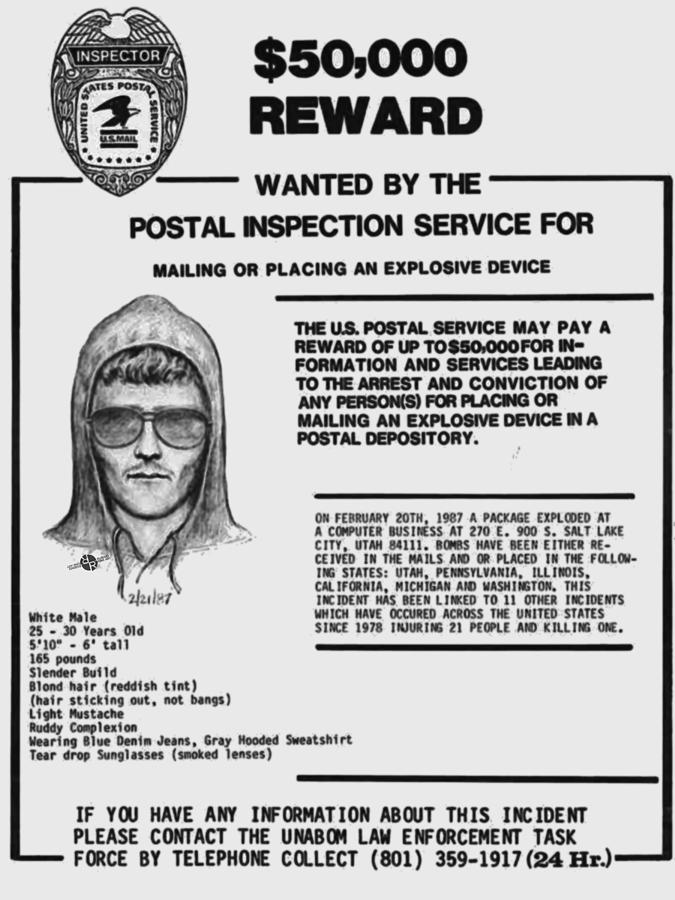

From 1978 to 1995, Kaczyniski mailed or hand-delivered a series of homemade bombs of increasing sophistication. He took great care not to leave any fingerprints behind and he purposely left misleading clues to confuse authorities.

His first bomb was meant for Buckley Crist, a professor of materials engineering at Northwestern University. Crist was suspicious of the package and called campus police. Officer Terry Maker opened it the package and it exploded, injuring Maker’s left hand. A second bomb in May, 1979 was sent again to Northwestern — this time it was graduate student John Harris who suffered minor cuts and burns when it exploded.

Kaczyniski’s next bomb was intended to blow up a Boeing 727, American Airlines flight 444, traveling from Chicago to Washington, D.C. The bomb was placed in the cargo hold and thankfully, a faulty timing mechanism prevented it from igniting. It did release smoke, forcing an emergency landing. Authorities said it had enough power to “obliterate the plane” had it exploded. It was then that the FBI opened the UNABOM case and led a task force made up of the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives and U.S. Postal Inspection Service. Analysis on the bomb materials proved fruitless — Kaczyniski’s homemade explosives were made with scrap materials found almost anywhere. Four more bombs caused unsuspecting victims burns and cuts from 1980-1985. The first serious injury occurred on May 15, 1985 at Berkeley when graduate students and captain in the U.S. Air Force John Hauser opened the package. He lost four fingers and vision in one eye. This bomb was followed by two more bombs in 1985 and then on December 11 of that year, the blast from a nail-and-splinter loaded bomb killed Sacramento computer store owner Hugh Scrutton. It was the first of three “Unabomber” casualties. Kaczyniski targeted another computer store owner, Gary Wright, in 1987 who suffered nerve damage when the bomb went off.

After nearly a decade, the FBI was nowhere close to catching the “Unabomber.” And then, he stopped sending bombs for a period of six years, from 1987 to 1993. The authorities thought he was gone — they surmised he died by accidental death or natural causes, or maybe he had a change of heart.

Kaczyniski’s reign of terror wasn’t over. He mailed four more bombs from 1993 to 1995 murdering two more people including Thomas J. Mosser, an advertising executive and Gilbert Brent Murray, a timber industry lobbyist. His other two bombs severely wounded and disfigured David Gelernter, a computer science professor at Yale University and Charles Epstein, geneticist at the University of California, San Francisco.

Kaczyniski’s bombs were often stamped with the letters “FC” and the FBI noted the theme of nature and trees since he often included bits of bark and branches in his explosive packages.

Manifesto

In 1995 Kaczyniski contacted the media; blackmailing the New York Times and Washington Post into publishing his 35,000 essay Industrial Society and Its Future. The FBI and media dubbed this the “Unabomber Manifesto” and in exchange for its release, word-for-word, he would “desist from terrorism.” In his Manifesto, Kaczyniski asserts the downfall of the human race can be attributed to the industrial revolution and modern, technological society. He claimed widespread psychological suffering had taken place because of technology’s destabilizing effect and he argues people spend too much time engaged in useless pursuits, such as consumption of entertainment.

“…our society tends to regard as a “sickness” any mode of thought or behavior that is inconvenient for the system, and this is plausible because when an individual doesn’t fit into the system it causes pain to the individual as well as problems for the system. Thus the manipulation of an individual to adjust him to the system is seen as a “cure” for a “sickness” and therefore as good.”

Kaczynski saw the only way of returning to “wild nature” and freedom was to destroy progress, which he believed was possible.

The Manifesto’s reception was regarded as a work of genius by some and entirely sane by others. It has been compared to Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World and George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four. UCLA professor James Q. Wilson, wrote it was “a carefully reasoned, artfully written paper … If it is the work of a madman, then the writings of many political philosophers — Jean Jacques Rousseau, Tom Paine, Karl Marx — are scarcely more sane.”

Arrest & Conviction

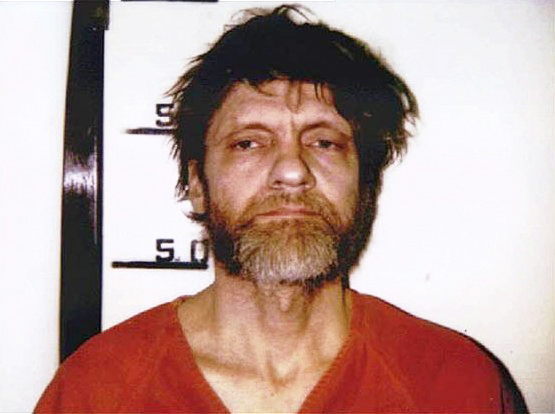

Following the publication of the Manifesto, David Kaczynski and his wife Linda noticed chilling familiarities between his brother’s letters and an earlier essay Ted wrote. For three weeks they poured over years of correspondence looking for tell-tale clues before contacting the authorities. Once convinced the Unabomber could be David’s brother, they hired an attorney who contacted a criminal profiler to analyze the letters and contact the FBI. At the time, agents were actively following up on over 2,000 tips and a recluse living in the backwoods of Montana didn’t seem to match their expectations — not until expert linguists analyzed the letters and essay and determined they were most certainly the same man.

FBI agents arrested Kaczynski on April 3, 1996, at his cabin, where he was found in an unkempt state. A search of his cabin revealed a cache of bomb components, 40,000 hand-written journal pages that included bomb-making experiments, descriptions of the Unabomber crimes and one live bomb, ready for mailing. They also found what appeared to be the original typed manuscript of Industrial Society and Its Future. By this point, the Unabomber had been the target of the most expensive investigation in FBI history.

A federal grand jury indicted Kaczynski in April 1996 on ten counts of illegally transporting, mailing, and using bombs, and three counts of murder. Kaczynski’s defense had attempted to use the insanity defense to avoid the death penalty but Kaczynski refused. He tried to fire his attorneys and attempted suicide by hanging on January 9. On the judge’s order, Kaczynski underwent a psychological evaluation by Sally Johnson who gave him a provisional diagnosis of paranoid schizophrenia. Regardless, he was determined to be fit to stand trial and instead pleaded guilty to all charged on January 22, 1998 in exchange for avoiding the death penalty. At the sentencing, Kaczynski displayed no emotion or remorse for his heinous crimes. The contents of his cabin were sold at auction and netted $232,000 for Kaczynski’s victims.

Today Ted Kaczynski is serving eight consecutive life sentences in a maximum-security prison in Florence, Colorado where he spends 23 hours a day in his cell. He maintains an oddly active connection to many people on the outside through letters and contacts the media with regularity. The Labadie Collection, correspondence since his arrest with over 400 people, is housed at the University of Michigan’s Special Collections Library. And his Montana cabin, seized by the U.S. government, is currently on display at the Newseum in Washington, D.C.