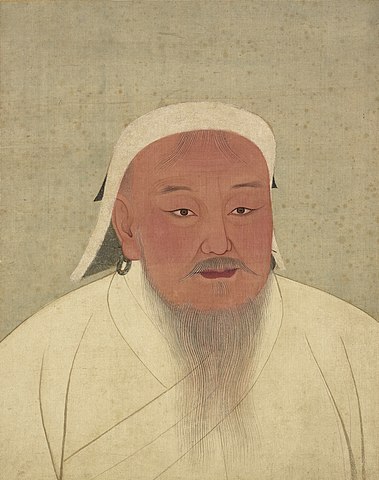

It’s one of the most chilling passages in military history. In the 13th Century Secret History of the Mongols, Genghis Khan’s quartet of elite generals are described thus: “They are the Four Dogs of Temujin. They have foreheads of brass, their jaws are like scissors, their tongues like piercing awls . . . In the day of battle, they devour enemy flesh. Behold, they are now unleashed, and they slobber at the mouth with glee.” Coming from an empire as bloody as the Mongols, these passages fairly drip with horror. But even among the Dogs of Temujin, one stands out as more-cunning, more sadistic, and more-terrifying than the others. His name was Subutai, Genghis Khan’s Dog of War.

A non-Mongol who joined the Khan’s tribe aged 14, Subutai blossomed into a master of battle. The Mongols’ greatest general, Subutai rode further, and conquered more than any other man in history. It was thanks to him that Russia was brought into the Mongol fold; that the Mongols reached Central Europe; that they came this close to taking Vienna. Yet despite being both brilliant and vicious, Subutai now is mostly forgotten. In today’s video, we’re looking back on the greatest, deadliest general to ever live.

The Cur

Although he would become the Mongols’ greatest general, Subutai was never destined to be one of Genghis Khan’s people. When he was born, around 1175 AD, it wasn’t onto the endless plains of the Mongolian Steppe, but into the dense, dark forests on the Western shores of Lake Baikal.

His tribe were the Uriangkhai, sometimes inaccurately known as the “Forest Mongols”. Inaccurate, because the Uriangkhai had almost nothing in common with their southern neighbors. Where the Mongols could ride day and night, the Uriangkhai used sledges. Where the Mongols were masters at weaponry, the Uriangkhai were better known for their metalwork.

But that’s not to say the two had nothing in common.

Every year, when the snows finally melted, the Mongols and the Uriangkhai would meet to trade. It was during one of these meetings that Subutai’s fate was sealed.

The story goes that Subutai’s father often traded with a Mongol known as Yesugei. Subutai’s dad wound up owing Yesugei a favor, and promised him his firstborn son. 18 years later, the Uriangkhai trader returned to the Steppe with Subutai’s older brother, Jelme, in tow, ready to fulfill the bargain.

But when he reached the Mongol camp, he discovered that Yesugei had died many years before. In his place was now his son, the outlaw Temüjin.

Rejected from his own clan, Temüjin was a nobody at this time. But a deal was a deal, and so Jelme joined him. Not sixteen years later, Temüjin would acquire a different name: Genghis Khan. And Jelme would make sure his younger brother got to join the Great Khan’s conquests.

Sadly, this neat origin story may be just that: a story. Fiction.

But what is true is that Jelme – for whatever reason – wound up joining Temüjin around 1187. Just three years later, he invited his younger brother Subutai. Subutai was by now 14. As was the custom, he was supposed to train in his father’s business, become a blacksmith, and take over as man of the house.

But Subutai clearly yearned for adventure. For a life like the one Jelme was leading, out on the endless, romantic plain. So, in 1190, he left the Uriangkhai behind. Abandoned the thick forests of his ancestors, and headed south, to where the action was.

And boy, what action it was.

In 1190, Temüjin was just setting out on the path that would soon see him unite the Mongols. But Subutai wasn’t yet a fighter. He still needed to learn the skills the Mongols valued in a warrior.

Luckily, his brother was by now one of Temüjin’s most-trusted advisors. Jelme ensured Subutai got the chance to learn horsemanship, how to ride day and night nonstop, and how to survive the alternating ice and fire of the Mongol plain.

By 1197, Subutai was ready for battle.

His first assignment was to help Temüjin wipe out some long-term rivals.

Back then, the Mongol steppe was still a fractured collection of tribes who enjoyed nothing more than bashing one another’s heads in and making off with their wives. One of these tribes, the Merkits, had done exactly this a while back with Temüjin’s wife, and now Temüjin never missed an opportunity to attack them.

Only this early version of Genghis Khan wasn’t just a rush in and kill them guy. He prefered stuff like spies and infiltration.

And that’s how Subutai came to appear in the Merkit camp, claiming he’d defected from Temüjin, offering his hosts intelligence on his former tribe’s movements.

“Merkit” apparently being Mongol for “gullible buffoons”, the tribe believed him, and Subutai lead them right into an ambush.

It was Subutai’s first serious taste of blood. It certainly wouldn’t be his last.

War Pigs

While Genghis Khan is mostly remembered today as a conqueror, he was also a great innovator. One of those innovations was the idea of promoting his generals based on skill, rather than kinship.

It was this enlightened policy that would allow the non-Mongol Subutai to rise to the very top. Not that progress was fast. In Temüjin’s clan you earned your stripes the hard way: through years and years of constant, bloody warfare.

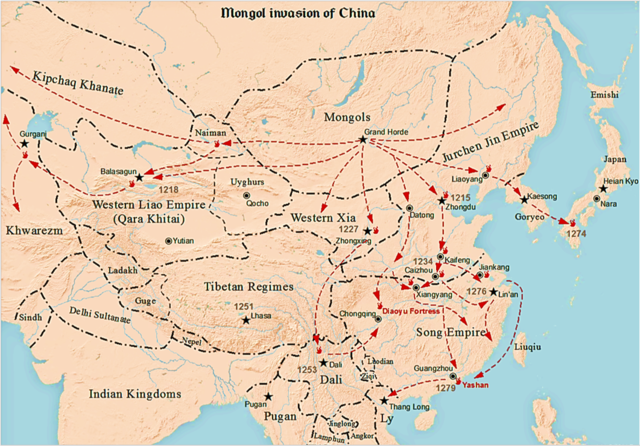

Subutai’s early adulthood was spent doing stuff like helping unite the Mongols, culminating in 1206 with Temüjin being proclaimed Mongolia’s “universal ruler” or Genghis Khan. He was part, too, of the subsequent assault on the Xia Xia kingdom, the first time the Mongols fought as a united force outside their homeland.

Importantly, he was also part of the gigantic war the Mongols undertook against the Great Jin dynasty of northern China. We say “importantly” because it was during this epic war that Subutai showed the first glimmerings of the great general he would become.

In 1211, Genghis Khan cooked up a plan to deliver an early body blow to the Jin armies with a surprise attack. Subutai’s role was to lead an army of 30,000 toward Jin territory from the north. When the Jin forces massed, Genghis Khan would attack with a larger force from the west, smashing them apart.

At first, the plan worked. Subutai rode down from the north, paraded his army around, all while doing his best to look nonchalant.

The Jin took the bait, massed their forces, and then were duly surprised when Genghis Khan came charging into their flank.

But then things started to go wrong.

The Jin put up an unexpectedly strong fight, refusing to give ground. Then Subutai’s army vanished from the field, allowing the Jin to focus on Genghis Khan. Had Subutai just bottled it? Had he fled? Since this video isn’t title “Subutai: the dude who ran away from battles” you can probably guess the answer to that question.

Rather than flee, Subutai had rode south hard, pushing his horses to the limit. Now, his army was swinging back up north, circling around the Jin, coming at them from behind.

The Jin never knew what hit them.

There was simply no way Subutai should’ve been able to ride that far and that fast. Yet here he was, suddenly leading thousands of Mongols in a surprise attack from the rear. It’s a mystery whether Subutai and Genghis Khan planned this beforehand, or whether Subutai took a gamble in the heat of battle.

Either way, the sneak attack made possible only by an impossible ride would become a Subutai hallmark.

Over the next few years, the Mongol conquests rampaged on. In 1214, the Jin were driven out their capital of Zhongdu – now Beijing – and the city burned to the ground.

Five years later, in 1219, Genghis Khan attacked the Central Asian Khwarezm Empire, beginning a war that would see his empire stretch from the Caspian Sea to the Sea of Japan.

Not that Subutai would witness this.

In 1221, Genghis Khan selected his loyal general for a special task. As the war raged in Khwarezmia, Subutai would take 20,000 cavalry west on a reconnaissance mission. It was the beginning of a process that would soon see Mongol hordes sweeping into Europe, destroying everything in their path.

It was also the beginning of Subutai’s rise from mere general to the greatest conqueror in history.

From Russia, with Bloodlust

Try to picture, just for a moment, what it must’ve felt like to be an Eastern European in the early 1220s.

Up till now, your comfortable worldview has essentially extended no further east than Jerusalem. China and the far east are vast, blank nothings where you suspect no humans really live. And then it happens. The first Mongol raiding party comes sweeping through the Caucasus and up into your backyard, bringing unprecedented devastation in their wake.

It must’ve been the 13th Century equivalent of a Martian invasion.

And Subutai was the mighty Martian warlord.

The speed of his invasion was shocking. In 1222, Subutai’s army reached Georgia, where they wiped the floor with their army. That done, they pushed west, reaching Crimea by early 1223.

It was at this point Europeans first made contact with the Empire that would nearly destroy them. As they reached Crimea, Subutai’s army had sliced their way through the nomadic Cumans.

But the Cuman leader had managed to escape, and gone running to his son-in-law, Prince Mstislav of Galich. And Galich in 1223 just happened to be part of the fabled empire of Kievan Rus. The forebears of modern Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus, the Princes of Kievan Rus were a loose alliance who together were one of the great forces of Europe.

So when Mstislav heard about these barbarians hammering at his gates, he forged a pan-Russian army to go teach them some manners. At first, Subutai seems to have realized he’d made a mistake. His forces fell back before the vast Slavic army.

For nine whole days, the Princes of Kievan Rus chased the Mongols east. They chased them all the way to the Kalka River, now thought to be the Kalchik River in Donetsk Oblast, Ukraine. Finally, in late May, Prince Mstislav forced a battle. His forces attacked the Mongol rearguard, annihilating them.

As the panicked Mongols retreated over the river, the Prince followed, determined to finish these heathens off once and for all.

At this point Subutai presumably gave a truly terrifying smile.

It had been a trap, of course. The moment the Russian armies were pinned with their backs against the river, the Mongols stopped their retreat, turned around…

…and that was it for the Princes of Kievan Rus.

It’s estimated that 90% of the Rus force was annihilated. 40,000 soldiers, 70 nobles, and six princes fell before Subutai’s sword. Among those captured was the Prince of Kyiv, who suffered the worst fate of all.

Rather than simply kill him, Subutai arranged to have him placed under floorboards, on top of which the Mongols held their victory party. A night of thousands of men franticly dancing atop him was enough to slowly crush the prince to death.

Yet this would be the finale of Subutai’s first journey west.

Despite the damage they’d unleashed, the Mongol army was a mere 20,000 strong, far too small for a serious campaign of conquest. So, after a journey that had taken them 8,850 km from their homeland – or about the distance from Anchorage, Alaska to Bogota – Subutai and his men turned around and rode home.

You can almost imagine the relief in Europe as this unstoppable new threat receded. A slow exhale of breath as people realized they weren’t doomed after all.

But this was a dangerous misreading of the situation.

Subutai might be gone, but he hadn’t forgotten those who’d tried to fight him. He would soon return.

When he did, it would be game over for Europe.

The Dog of War

For the next 13 years, Subutai stayed near Mongolia, witnessing the empire transform. First came Genghis Khan’s death in 1227, followed by the elevation of his son Ögedei to leader.

Then came the consolidation of power, as Ögedei imposed taxes and bureaucracy on conquered peoples.

As all this was going on, Mongol ambitions stayed small. Although it was in this period that Jin Northern China was finally smashed, more remote conquests were postponed. Finally, though, the empire was stable enough that Ögedei told Subutai to head west again.

Enerelt at English Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0

It was music to the old War Dog’s ears.

By now, the legendary general was a man of sixty. His days of riding were over, and he’d grown so fat he had to travel in a carriage. Yet the tactical genius that had served him so well had only improved with age. When Subutai returned to Europe, it would not be on a mere reconnaissance mission, but a full-blown campaign of conquest.

Incredibly, in the 13 long years since the Mongols first appeared, Europe still hadn’t got its defenses sorted. The Russian princes were busy squabbling among each other. While a united force might be forged, it would take time.

So Subutai simply decided he wouldn’t give them even a spare second to think about it.

That same year, 1236, the Mongol army crossed the Volga River .

Its head was nominally Batu Khan, grandson of Genghis. But the one in charge of strategy, in charge of terror tactics, was Subutai. And if there was one thing Subutai excelled at, it was terror.

The first year of the invasion was spent mopping up the semi-nomads of Europe’s far east, the Volga Bulgars, Kipchaks and Alans. As one by one Europe’s satellite tribes fell, Subutai sent ambassadors to the princes of Kievan Rus, telling them to surrender without resistance, or watch their whole world burn.

When the princes refused, we can only imagine Subutai smiled his terrible smile.

On 21 December, 1237, the city of Ryazan, some 200km from Moscow, became the first to fall to Subutai’s forces.

Women were dragged, screaming through the streets. Children were shot full of arrows and thrown into burning buildings. Men were disemboweled while their families watched. At the end of the slaughter, Ryazan was no more. Only a handful were left alive, spared by Subutai so they could spread the tale of his savagery.

It was a tale that would soon acquire many more chapters. After Ryazan, the Mongols moved northeast. Kolomna fell, then Suzdal, then Moscow.

Yet even as Moscow burned, the Russian princes still couldn’t coordinate a defense. Still couldn’t forget their petty rivalries long enough to defeat the Dog of War.

On February 7, 1238, the War Dog fell upon the city of Vladimir.

Its grand prince, Yuri II, fled the carnage, assembling an army to fight back. He returned to the smoking city, only to get pinned down by a blizzard. As Yuri and his army waited for the weather to lift, they wondered where the Mongols were. If they were hiding to the North, to the East, or somewhere else entirely.

Finally, the storm lifted enough for Yuri to send out scouts. They came back with a horrifying answer.

The Mongols were hiding to both the North and East. And the West and South. Their 200,000 strong force had completely surrounded the Russians.

In the subsequent battle, Subutai systematically slaughtered the entire Russian army. At its end, he had Yuri dragged before Batu Khan and ordered to kneel.

When the Grand Prince refused, his head was sliced clean off.

By April of 1238, Subutai had done the impossible. He’d invaded Russia. In winter. And he’d won. 12 cities were in ruins, the northern principalities had been laid waste to.

But this, incredibly, was just the warm-up act.

Before Subutai was done, the whole of Europe would cower before him.

Apocalypse Europa

In late 1240, the first Mongol warriors were sighted from the walls of Kyiv. In those days, Kyiv was the center of the Orthodox faith, one of the three great cities – along with Rome and Constantinople – of Christianity.

Well, it was until December 6, anyway.

That day, the Mongols breached the city walls. Everyone inside was killed, leaving such a pile of corpses that the streets were still littered with bones nearly a decade later. Yet Kyiv’s fall was just the opening salvo for the next act of Subutai’s invasion.

Subutai’s plan was to attack the Kingdom of Hungary, home to one of Europe’s greatest armies. But rather than just go charging in, he split his forces in two, sending 30,000 north under a warrior named Kaidu.

It was Kaidu’s forces that torched Krakow, and drove the citizens of Wroclaw into flight. It was Kaidu’s forces who killed the Silesian king Henry the Pious, and so effectively destroyed his army that they were able to fill nine sacks with the severed ears of the dead.

But it would be Subutai alone who annihilated Hungary.

In spring of 1241, Subutai divided his forces into four columns, and marched on the kingdom.

As this Angel of Death approached, King Bela IV summoned an army 100,000 strong. They amassed on the swollen shores of the Danube just as Subutai’s party appeared.

But if Bela thought he had the situation under control, he was badly mistaken. As Bela marched out east to fight, the smaller Mongol army fell back. They retreated for 9 whole days, until they had crossed the one small bridge over the wide, unfordable Sajó River.

If this sounds familiar, it’s because these are the exact same tactics Subutai had used against the Princes of Rus nearly two decades earlier. But Bela wasn’t an idiot. He waited across the stone bridge, refusing to take the bait. Daring the Mongols to come to him.

So they did.

On April 11, 1241, the Mongol force attacked across the bridge at daybreak. Although the Hungarians were taken by surprise, they weren’t broken. They managed to rally. It even looked like a Hungarian victory might be on the cards.

But if Bela had had any advisors from Jin China, they would’ve been able to tell him what a grave mistake he was making. They would’ve been able to ask the question that would soon doom the whole of Hungary:

Where was Subutai?

It turned out the general had found a way to ford that “unfordable” river they were all fighting on, making one of his trademark impossible cavalry rides to cross via some far-off marshland. Now 30,000 bloodthirsty Mongol warriors were bearing down on the Hungarian flank, their teeth bared; War Dogs ready to devour their prey.

The impact shattered the Hungarian army. As the Mongols closed in, Subutai kept a gap in the ranks, almost daring the enemy to escape.

It was an obvious trap. But the panicked Hungarians had no other option.

They fled through until a column of screaming, terrified refugees was pouring off the battlefield, their weapons discarded. Finally, when the army was in complete disarray, the trap sprang shut.

Two columns of fresh Mongol horsemen appeared, charging down the fleeing soldiers.

One by one they were slaughtered. When the soldiers were all dead, the Mongol forces then rode into nearby villages and put everyone to the sword.

By the end of the massacre, up to 70,000 Hungarian bodies lay strewn across the plain.

With them had fallen Europe’s last great line of defense. There was now nothing between the Mongols and the Atlantic, nothing between Subutai and the complete conquest of Europe. But the old War Dog would never get to fulfil his dream. The Mongols would never conquer any further west than Hungary.

Even at the pinnacle of his triumph, Subutai’s war days were nearly over.

The Last War Lord

The early winter of 1241 was spent teaching the Hungarians a bloody lesson. Subutai rode from end to end of the kingdom, destroying any settlement in his path. Buda and Pest were both burned. The town now known as Esztergom went up in flames.

By the time December came, it’s been estimated up to 50 percent of Hungary’s population had been massacred.

And still Subutai’s thirst for blood hadn’t been quenched.

As that dark December of 1241 gave way to a January that was bleak and gray, the Mongols began to push west again. Subutai sent a column down into northern Italy, and instructed reconnaissance units to scout the Danube valley.

All across Europe, petrified peoples waited for the hammer to fall. As Mongol raiders were spotted from the walls of Vienna, it must’ve felt like the continent’s time had come.

And then, Subutai’s army just stopped.

As Europe watched and trembled, the Mogol armies halted their advance. Fell silent for weeks on end. At the end of that, they suddenly packed up, turned their horses around and – incredibly, unbelievably – rode back home.

Today, what caused the Mongol retreat is a source of controversy.

The main theory is that news of Ögedei Khan’s death on December 11, 1241 finally arrived, necessitating a long ride home to help elect the new Khan. However, there are other theories linked to the miserable weather that decade, or the unavailability of food in famine-stricken areas.

But whether it was protocol or rain, turn back the Mongols did.

It’s said Subutai didn’t want to go. That the Dog of War gnashed his teeth and begged to finish his mission, the thing he was born to do. But Batu Khan ordered him. And, like a good dog with its master, Subutai eventually obeyed.

Not that the ride back was exactly peaceful.

On the return journey, the Mongols swept down through Croatia, Bosnia, Albania, and Bulgaria, doing their usual slaughtering. On the fringes of Central Asia, Batu Khan stayed behind to establish the Golden Horde, the Khanate that would be one of the world’s great powers for centuries.

But these were just distractions, postscripts to the great adventure. It was time to go home now, time for the story to end.

At last, after a ride many thousands of kilometers long, Subutai returned to Mongolia.

And so his life of adventure gave way to a singularly unadventurous retirement. Oh sure, he was still respected. When a Franciscan monk visited the Mongol court in 1247, Subutai was practically royalty.

One year later, in 1248, Subutai drops out the historical record.

One story says he spent his old age helping to raise his grandchildren. Another says he accompanied one of his sons back west to the Golden Horde, where he lived out his last days on the fringes of the continent he’d once come so close to conquering.

The date of Subutai’s death, or even how he died, is unknown. But what’s not in doubt is his legacy.

It’s said that Subutai in his long career conquered 32 nations. That the land distance he covered with these conquests was nearly 10,000 km, enough to put any other great conqueror to shame. Alexander the Great, Julius Caesar, Napoleon… all these guys are mere pygmies next to Subutai.

Yes, he was a sadist, a killer, and a bloodthirsty maniac. Yes, he used his gifts in the service of a brutal empire.

But Subutai was never destined to be a great thinker or artist. He wasn’t made to be a peacemaker. Subutai was built to accomplish one thing only: to fight. To fight so hard that he’d become the greatest warrior the world had ever known.

On that count, at least, the old dog succeeded.

Sources:

Link to the only major book on Subutai: https://www.amazon.com/Genghis-Khans-Greatest-General-Subotai/dp/0806137347

Detailed article from Military History: https://www.historynet.com/right-hand-khan.htm

Longer-form biography, two parts: https://www.camrea.org/2016/10/24/subutai-dog-of-war-sophisticated-military-strategist-behind-genghis-khans-conquering-empire-part-i/

https://www.camrea.org/2016/10/31/subutai-dog-of-war-silent-insatiable-and-remorseless-part-ii/

Sketch of life: https://mongolhistorypodcast.wordpress.com/subutai/

Another brief sketch: https://www.warhistoryonline.com/war-articles/subatai-dog-of-war-mongol-empire.html

Some details of his invasion of Europe: https://www.ancient.eu/article/1453/the-mongol-invasion-of-europe/

As above: https://www.ancient.eu/Batu_Khan/

Brief overview of the western campaign by Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/place/Mongol-empire/The-period-of-relative-unity-1227-60#ref341054

Genghis Khan’s life: https://www.history.com/topics/china/genghis-khan#section_2

The Mongol Empire in retrospect: https://www.historyextra.com/period/medieval/the-brutal-brilliance-of-genghis-khan/