Today, we take a look at a pirate unlike any other – Stede Bonnet, the Gentleman Pirate, so called because he came from a life of luxury and leisure. He was wealthy, he was well-educated, he was influential in high society. And yet, he left that life behind and, instead, decided to become a pirate.

His motivation, whatever it was, already makes him unique among the pirates we have covered on this channel, but another original aspect of Bonnet was that he was completely ill-prepared for life as a pirate captain. He didn’t know how to sail, he didn’t know how to navigate, and he didn’t know how to fight, but that did not deter him in the slightest, although it did cause some friction with his men.

This almost makes him sort of a comical character, especially when compared to his peers but, to everyone’s surprise, he wasn’t the most terrible pirate in the world. He took his fair share of prizes, and secured long-lasting notoriety for himself, thanks mainly to his association with Blackbeard. In the end, though, Stede Bonnet proved to be a tragic figure, as the rest of the world was not impressed or amused by his antics, and, ultimately, he shared the same harsh fate as most of his confederates.

Early Years

Stede Bonnet was born in 1688, on the island of Barbados. He came from a wealthy family as his parents had a large plantation a couple of miles from the Barbadian capital of Bridgetown, and he inherited it all once his parents died. He received a good education and was brought up to be a proper and upstanding member of society.

As a young adult, Bonnet married a woman named Mary Allamby in 1709, and together they had four children. Through the years, he saw his standing in society steadily improve. His wife was also the daughter of a wealthy planter so he got a large dowry by marrying her, and his own plantation seemed to thrive. He joined the British army and served in the local militia where he attained the rank of major. In other words, Stede Bonnet seemingly had everything a man of that era could want.

And yet, he did something strange in 1717, something that puzzled his contemporaries and still puzzles historians to this day. He gave up his life and decided to become a pirate. What exactly prompted Bonnet to do this remains a mystery. The main motives why men turned to piracy in those days were because they either did not know how to make money any other way, or because they wanted to escape the oppression of their governments, or because they were forced into it.

None of the above applied to Stede Bonnet. He was considered a “gentleman of leisure and wealth,” who had the money, the influence, and the status to live out all his years in comfort. But, for some reason, this did not appeal to him. Instead, he preferred to risk his life on the high seas.

So why did he do it? Both his contemporaries and modern historians have offered their opinions. Some simply believe that he was bored and wanted a bit of excitement in his life, but, if this is true, then Stede Bonnet should be in contention for the most extreme mid-life crisis in history. Others thought that he suffered from some kind of mental illness, while Charles Johnson, in his seminal account A General History of Pyrates, claimed that Bonnet wanted to leave his old life behind due to “some discomforts he found in a married state,” implying that Stede Bonnet was doing all of this just to get away from his wife. There is also a possibility that his financial situation may not have been as comfortable as we previously suggested, as there is a record of him borrowing £1700 at the start of the year. Maybe a poor harvesting season left him in dire straits and Bonnet thought he had no alternative but to turn to piracy, or maybe he had already made his mind up and knew he would never have to pay the loan back. Ultimately, all of these hypotheses remain guesswork since Bonnet himself never gave an explicit reason.

Speaking of Charles Johnson, we often start off these pirate bios specifying that he is the main source and is not considered particularly reliable, so everything has to be taken with a grain of salt. Well, that is not necessarily true in this case because, although A General History of Pirates remains an important source, we have a more trustworthy secondary one. Because Stede Bonnet was arrested and tried for piracy, a detailed account of his trial in South Carolina was published and survives to this day, so we have corroboration on the things he did as a pirate.

A Pirate’s Life for Me

Like we said, in 1717, Stede Bonnet left his life behind and became a pirate. Unlike every other pirate captain, Bonnet did not steal his ship, he purchased it. It was a sloop which he named the Revenge and had it fitted with 10 cannons. He also hired his crew – around 70 to 80 men who received a monthly salary paid out of Bonnet’s own pocket instead of simply awarding them a share of the plunder. This was probably done more out of necessity, though. Seeing as how a pirate crew could depose the captain for being incompetent and then vote on somebody else to take his place, this was probably the only way that Bonnet could have maintained his captaincy given that he knew almost nothing when it came to sailing, navigation, or maritime warfare.

Once Bonnet had his ship ready and his crew assembled, he needed to wait for the right opportunity. The Revenge stayed quietly in the harbor for a few days, and everyone who inquired was simply told that Bonnet purchased it to start trading with the nearby islands. Then, one night, without a word to his family or friends, the captain abandoned his life of leisure and set sail on the high seas, headed for the eastern coast of North America.

You might think this haphazard approach to piracy would be a recipe for disaster, but Stede Bonnet was surprisingly successful. He took his first prizes off the coast of the Colony of Virginia, where he plundered not one, not two, but four ships in a short amount of time: the Anne, the Turbet, the Young, and the Endeavour. Two of them sailed out of Scotland and one out of England, and those were free to go after being plundered. The Turbet, however, had set sail from Barbados, and Bonnet insisted on having it confiscated and burned down. He would go on to repeat this with other ships from his native island. We’re not sure if he did this to try and prevent word of his actions from reaching back home or if he harbored some kind of resentment for Barbados.

Anyway, after Virginia, Bonnet headed for New York, where he captured another sloop and then resupplied his ship. According to his trial documents, by August 1717, the Revenge was already heading back south to the coast of South Carolina, when he captured two more ships. First was a sloop from Barbados, carrying sugar, rum, and slaves, and captained by a man named Joseph Palmer, and the second was a brigantine from New England under Captain Thomas Porter. Again, Bonnet burned down the ship from Barbados.

This initial run proved to be quite successful, although, realistically, this was more due to the skill and experience of the crew rather than Bonnet himself. By this point, most of the pirates probably figured out that their captain was a complete rookie when it came to all seafaring matters, and some discontent had already started brewing. It was decided that they would make land for a while, and go somewhere where they could actually spend some of their ill-gotten gains. The Revenge set sail for Nassau, in the Bahamas, which was a pirate haven at that time. There, Stede Bonnet made the acquaintance of numerous other sea dogs such as himself, and among them was Captain Edward Teach, better known as the infamous Blackbeard.

Bonnet Meets Blackbeard

Right off the bat, we should mention that, from this point on, the careers of Blackbeard and Bonnet intertwine for a while. We’ve already done a video on Blackbeard so, if you would like to get this story from his perspective, as well, why not give it a little look-see.

Anyway, Blackbeard was a skilled and experienced captain, not to mention that he was respected and feared by his crewmen. He was the antithesis of Stede Bonnet and yet, somehow, the two struck up a relationship and decided to sail together for a while. Many would say that Blackbeard was simply using Bonnet to strengthen his own fleet, and they would probably be right. This was before Edward Teach had gotten his hands on the Queen Anne’s Revenge, his main flagship for most of his piratical career. Having Bonnet’s Revenge on his side would have been a significant advantage.

This worked out well for the captain from Barbados, at least at first, as having someone like Blackbeard in charge probably quelled any desire to leave or revolt that might have been developing among Bonnet’s crew. So the fleet left Nassau with Stede Bonnet officially a guest aboard Blackbeard’s ship, while a Lieutenant Richards had been given temporary command of the Revenge.

They proved to be a formidable force in the waters surrounding the Bahamas, and took at least a dozen prizes on their way to the east coast of America. Again, going by court records, by the time they reached North Carolina, they had four ships in their fleet and between 300 to 400 fighting men. You might think this would be a good thing for Stede Bonnet, as he set out to be a pirate captain, not actually knowing anything about what that entailed, and was now part of one of the most powerful and feared convoys in American waters.

However, that was not the case. In fact, Bonnet was quite depressed, as he realized what he truly was – a prisoner who willingly gave up command of his ship to his own captor. Sure, on the surface, his relationship with Teach was still cordial, and he wasn’t deprived of his share of the plunder, but Bonnet understood that this would only continue as long as he played the role of the content guest. Any attempt to reclaim his authority over the Revenge would have likely put an end to all niceties and, worst of all, Bonnet would have probably discovered that most of his men preferred to sail under Blackbeard, anyway.

In private, Bonnet confessed to some of the men who were loyal to him that he felt tired and shameful for his actions and, if possible, he would have gladly left the pirate life behind, and started fresh somewhere in Spain or Portugal, as he could not bear to face a fellow Englishman. Alas, it seemed that the only way he would regain command of his ship was if Blackbeard decided to surrender it.

According to certain versions of the story, this is exactly what happened. They say that once Blackbeard captured La Concorde, which he renamed to the Queen Anne’s Revenge, he had no more need for Bonnet’s ship and let him go independent again. Once this happened, Bonnet immediately forgot any plans about giving up the pirate life and assumed command of the Revenge again. However, this newfound autonomy did not last long. His inexperience once again caused problems with the crew, after an ill-fated attempt to plunder a well-armed merchantman named the Protestant Caesar in the waters of Honduras in the spring of 1718. Not only did he fail, but Bonnet was injured in the skirmish, leaving him unfit for duty. Soon afterwards, he ran into Blackbeard’s fleet again, and his own men pleaded with the other captain to assume command of the Revenge once more…which he did, and Bonnet found himself again to be Blackbeard’s guest/prisoner. Some accounts, like that of Charles Johnson, make no mention of this brief period of independence, so whether or not it happened is a matter of debate.

Betrayal & Pardon

We do know, however, when Blackbeard and Bonnet severed their ties completely, just a few months later. In May 1718, Blackbeard used his fleet to blockade the port city of Charles Town, South Carolina, or Charleston, as we call it today. Afterwards, the ships traveled to Topsail Island, off the coast of North Carolina, which was used as a popular resting and hiding spot for pirates. There, the Queen Anne’s Revenge ran aground and became unsalvageable, as did one of the smaller sloops in the fleet. With two ships lost, Blackbeard decided that it might be a good idea to get a pardon from the Governor of North Carolina, a man named Charles Eden.

All pirates were free to do this. In an effort to make the waters of the Atlantic safer, King George I of Britain issued a proclamation “For Suppressing Pirates in the West Indies,” which became known as the King’s Pardon of 1718. Basically, it was a one-time offer available to any pirate, no matter how heinous their criminal activities were. As long as they applied before the deadline, not only would their slate be wiped clean, but they could also receive a commission to become a pirate hunter and take down their former confederates who did not accept the king’s pardon.

Blackbeard and Bonnet traveled to the city of Bath and both obtained pardons for them and their crews from Governor Eden. Blackbeard and his men then left on their way, but Bonnet stayed behind for a while, hoping to get permission to become a privateer. During the time that he had been a pirate, England went to war against Spain, so he thought that he could basically continue where he left off and be on the right side of the law by only targeting Spanish merchants. Eventually, Bonnet was told that he could go to the island of St. Thomas from where he could obtain a privateer’s commission.

When he finally returned to his ship, Bonnet discovered one last treachery from Blackbeard. The other pirate captain had stripped the Revenge of all supplies, loot, and useful materials, placed them aboard the other remaining sloop and took off. Many scholars now believe that this had been his plan all along and that he intentionally wrecked the Queen Anne’s Revenge to have an excuse to disband his large crew.

As for Stede Bonnet, he might have been stranded on Topsail Island, but at least he was in command of the Revenge again. Furthermore, his crew hated Blackbeard now, so it was decided that, once the ship was repaired and seaworthy again, they would go in pursuit of the one who betrayed them. Once they set off, they soon noticed a group of 20 or so men marooned on a nearby sandbar. Bonnet rescued them and discovered that they were part of Blackbeard’s crew, left behind because Blackbeard had too many hands on deck for just one ship. As you might imagine, they also wanted revenge against their former captain and were glad to join Bonnet’s ranks.

Bonnet was still much more inexperienced in matters of warfare than Blackbeard, but he had the bigger ship, the bigger crew, and his men were highly-motivated by their desire for vengeance. It would have been an interesting part of pirate history and a fitting end to their chapter if the two met up and engaged in one final battle. Unfortunately, this never happened. Bonnet heard word that Blackbeard had moored his ship in an estuary called Ocracoke Inlet, but by the time he got there he found it empty and he never again encountered the treacherous Blackbeard.

A Pirate’s Life for Me…Again

With revenge no longer an option, Bonnet wanted to return to his previous plan – travel to St. Thomas and receive a letter of marque to become a privateer against Spain. However, there was a problem because Blackbeard had stolen all of their supplies. They needed water, food, and liquor, but that posed another problem. They couldn’t just plunder a ship. Technically, they weren’t pirates, anymore, as they had accepted the king’s pardon. This was only a one-time deal, and if they broke it now, there would be no more turning back. They couldn’t buy anything, either, because Blackbeard also made off with all their treasure.

In the end, they encountered a merchant ship full of goods and forced it to trade with them. They made off with barrels full of pork and bread and, instead, left behind a few casks of rice and an old cable, which was the chain holding the anchor. They were probably hoping to get away with it on a technicality, since they committed an act of trade, not piracy, even though it had been, basically, forced at gunpoint and heavily one-sided.

They still didn’t have any liquor, though, and for pirates, they might as well not have had any air to breathe. That is why a couple of days later, they plundered…I mean, “traded” with another ship which provided them with two hogsheads of rum and two of molasses. It is uncertain what Bonnet planned to give them in exchange, because the other ship took advantage of an opportunity and fled before their transaction was complete.

After this, all pretenses were dropped and they became full-fledged pirates again, pardon be damned. As a precaution, though, Bonnet did change his name to Captain Thomas and the name of his ship to the Royal James, hoping that maybe this might conceal his identity.

Bonnet spent a short time as Captain Thomas, but it was his most successful. Clearly, he was no longer the same inexperienced, naive man that he was when he started. He was more respected, even more feared. Some historians claim that Stede Bonnet was one of the few real pirates to actually make his prisoners walk the plank, as this was a practice mostly popularized by the book Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson. Bonnet prowled the waters of the Carolinas, traveling up north into Virginia and Delaware, capturing almost a dozen ships, of which two he kept and added to his fleet.

Battle of Cape Fear River

After a few profitable months at sea, Bonnet needed a place to make land and careen his ship for repairs. He chose the estuary of the Cape Fear River in North Carolina. Hurricane season was also approaching, so this was intended to be quite a long stay.

Unfortunately for Bonnet, these last few successful months also increased his profile significantly. Charles Eden, the Governor of North Carolina, might have been somewhat indifferent to pirate activity, but his neighboring counterparts were not as amenable. The governors of the colonies knew they had dangerous pirates in their waters and wanted them dealt with. Consequently, the Governor of South Carolina, Robert Johnson, ordered a man named Colonel William Rhett to arm two pirate hunters and set sail to rid the colony of any pirates. The same thing happened with the Governor of Virginia, who sent out his own man to take down Blackbeard.

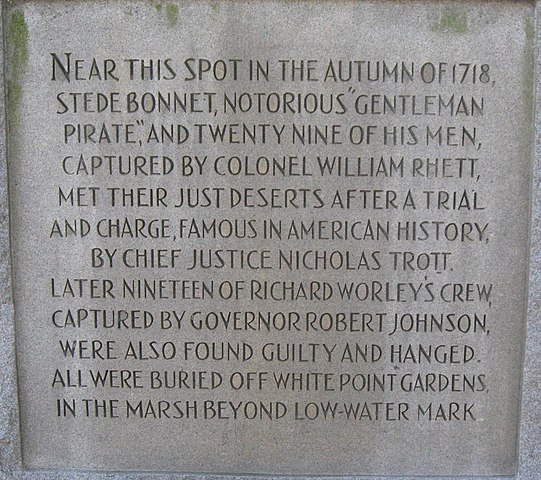

A memorial in Charleston commemorating the hanging of Stede Bonnet at White Point.

As far as Rhett is concerned, we’re not sure if he specifically targeted Stede Bonnet or if he intended to attack any pirate he encountered. Some have said that he simply stumbled upon Bonnet’s fleet while looking for Charles Vane, another infamous pirate you will likely see on this channel one day. Either way, Rhett set out in September, 1718, in two sloops, the Henry and the Sea Nymph, and soon received word of several pirate ships anchored at Cape Fear River.

Colonel Rhett reached Bonnet’s location on the night of September 26. The fight commenced the next morning, as Bonnet wanted to sail past the pirate hunters and head for the ocean. However, the river was not wide enough, and during the chaos, both of Rhett’s ships, as well as the Royal James, were grounded in shallow water. After hours of fighting, the South Carolinians started to gain the upper hand. At one point towards the end, Bonnet allegedly wanted to blow up his ship rather than be captured, but he was stopped by his men who decided to surrender. Ultimately, Stede Bonnet and 33 of his men survived the battle, were arrested and taken to Charles Town.

As a gentleman, Bonnet was given preferential treatment and was allowed to stay in the house of the provost marshal. On October 24, he actually managed to escape, but was only at large for four days before being captured again.

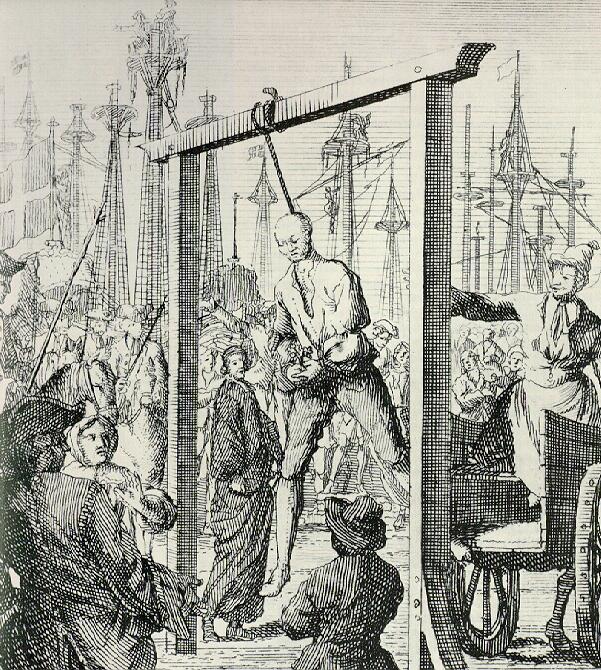

His men didn’t have it so good. Of the 33, 29 were found guilty of piracy and sentenced to death, and they were all hanged on November 8. A few days later, Bonnet’s trial took place and he, too, was found guilty and sentenced to die.

His date of execution was scheduled for December 10, so Bonnet still had some time to try and evade his ghastly fate. He begged, he argued, he pleaded, he tried blaming Blackbeard, he wrote letters to anyone who would listen in an attempt to get his sentence commuted. He managed to gain a lot of public sympathy, and even his captor, Colonel Rhett, was moved to the point that he offered to travel with Bonnet to England for a new trial. The gentleman pirate used his pleas and his tears to move everyone, except for the one person who mattered – Governor Johnson.

Despite public pressure, the governor remained steadfast in his decision, arguing that Bonnet had already broken his word once. So on December 10, an almost insensible Stede Bonnet was dragged to the gallows and, in front of a crowd that exhibited more pity than contempt or hatred, he was hanged. Nowadays, a historical marker is all that remains of the spot where the “notorious gentleman pirate and twenty-nine of his men” met their end.