According to legend, Spartacus’s wife walked in on her sleeping husband one night to find that a snake had wrapped itself around his face. Instead of being alarmed, she took this as a prophecy. Just like the serpent surrounded itself around the warrior’s head, so shall Spartacus be enveloped by a “great and fearful power”. One thing the woman could not see, however, was if this power would lead her husband to glory or disaster.

In the end, you will have to decide for yourself what the outcome was. Spartacus might have lost the war, sure, but not before making the all-powerful Roman Republic tremble at his feet. At a time when the might of Rome was continuously expanding all over the Mediterranean, a mere slave led an uprising the likes of which the world had never seen. He defeated wave after wave of Roman armies and looked, for a while at least, powerful enough to march on Rome itself.

His actions turned Spartacus into much more than a warrior. He became a symbol in the fight against oppression. A symbol which is still pervasive today, over 2,000 years later.

They say that history is written by the victors so, in that case, Spartacus’s omen was, indeed, one of glory. Nobody mentions the success of Crassus in putting down a slave uprising. Instead, they talk about the triumph and the bravery of Spartacus.

Early Years

Unsurprisingly, details are scarce regarding Spartacus’s life before he rose up and became the bane of Rome. Even the particulars we do know cannot be taken for granted because different ancient sources give varying accounts.

Everyone seems to agree that Spartacus was a Thracian born sometime around the year 111 BCE. Plutarch, one of the main sources for the “War of Spartacus”, as he called it, referred to the warrior as having “nomadic stock” and described him as being sagacious and culturally superior, practically “more Hellenic than Thracian”. Some modern scholars have speculated that the word “nomadic” was a mistranslation made later and that Plutarch, actually, referred to Spartacus of being of “Maedi stock”. The Maedi were a Thracian tribe from those times which existed in modern-day Bulgaria.

Eventually, Spartacus ended up fighting in the Roman army as an auxiliary unit. At one point, the Thracian earned the scorn of the Romans who captured him and sold him into slavery. Again, sources vary as to the reason why – some say that Spartacus deserted, others that he led raiding parties, or, perhaps, both.

Life as a Slave

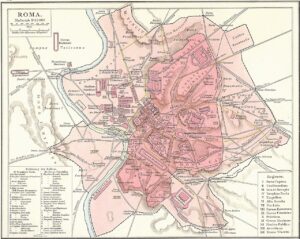

As a slave, Spartacus caught the eye of one Lentulus Batiatus, a Roman who owned a gladiator school called a “ludus” in Capua. He was always on the lookout for strong Gauls and Thracians who could shed some blood for the pleasure of the crowd.

In the arena, Spartacus took on the role of a heavyweight gladiator called a “murmillo”. The look of this warrior is a Hollywood favorite and will be familiar to anyone who saw or played anything set in gladiator times. The murmillo wore a full bronze helmet and heavy arm, leg, or shoulder guards. However, he kept his chest bare which often allowed warriors to display the tattoos or battle scars they accrued over the years. The gladiator typically wielded a large shield called a “scutum” and a straight broadsword called a “gladius”.

Although Spartacus has always been depicted in movies and TV shows as a prodigious fighter, we actually do not know anything about his success in the arena. Since these battles were usually to the death, he was, presumably, skilled enough to survive until the uprising started. Either that or he was entertaining enough to convince the crowd to spare him, even if he lost.

The Start of the Uprising

In the year 73 BCE, Spartacus was part of a plot to escape Batiatus’s gladiator school. The number differs – Plutarch says 78 slaves armed themselves with utensils from the kitchen, defeated the guards and made a run for it. During their escape, they ran into carts full of gladiator weapons being sent to another city. They plundered the wagons and armed themselves properly.

The former slaves decided to seek refuge on Mount Vesuvius which offered a stronger defensive position. On their way there, they recruited other slaves, as well as freemen who wanted to join their cause.

Ancient sources never really made it clear what exactly Spartacus did or said to the other slaves to convince them that he should be their leader. One factor which certainly played a part was the fact that the men split all their plunder equally. But it should be mentioned that historians also named two Gauls – Crixus and Oenomaus – as leaders of the revolt. While some described them as being the equals of Spartacus, others like Appian referred to them as subordinate officers.

The Battle of Mount Vesuvius

It is fair to say that when the Roman Senate heard about Spartacus and his little uprising, they did not take it too seriously. We may mock them for it now but, back then, this made some sense. Rome had quite a few other problems on its hands that required its attention and, more importantly, its soldiers.

In the Iberian Peninsula, Rome was engaged in the Sertorian War against Quintus Sertorius, a former Roman statesman who chose the losing side during the Second Civil War of the Roman Republic, but refused to concede defeat.

Over in Asia Minor, Rome was fighting the Third Mithridatic War against the Kingdom of Pontus led by Mithridates VI. This eventually resulted in a decisive victory for Rome and the end of the Pontic Empire, but not until ten more years of vicious battles.

As you can see, Rome had its plate full. Therefore, the revolt of the gladiators was dismissed as nothing more but a crime wave that could be solved with a cohort or two. In charge of this force was a praetor named Gaius Claudius Glaber of which we know almost nothing. His name suggests he could have had some kind of distant connection with the influential Claudii family, but, really, his only appearance in the history record is his battle against Spartacus. He is never mentioned again – whether this means he died in battle or he never did anything else of note, we just don’t know.

Anyway, Glaber’s army consisted of approximately 3,000 militia, not proper Roman legionaries. Again, the fact that the Senate sent an unproven military commander leading untrained militia revealed how little they were concerned with this uprising.

Glaber and his units chased the gladiators to their camp on Mount Vesuvius and laid siege on the only road down the mountain. His plan was to simply wait for the insurgents to starve to death. It seemed like a fine strategy, albeit a tad unoriginal.

Spartacus did not have this problem. In fact, his side deployed a much more novel game plan. He knew that Glaber was only paying attention to the side with the descent because all the others consisted of steep cliffs which were, seemingly, impassable. However, he and his men made rope ladders out of wild vines that were plentiful in the area and rappelled down undetected by the Romans. They then surrounded Glaber’s camp and easily defeated his forces in a surprise attack.

In the end, all this expedition managed to do was to supply the rebels with better weapons and armor and to help bolster their numbers as more people heard of their exploits.

The Second Expedition

On the second attempt, Rome sent another praetor named either Publius Varinius or Publius Valerius. There are no juicy details to share regarding these fights. Just the fact that Spartacus and his men triumphed again. First they defeated one of the praetor’s lieutenants named Furius who had two thousand soldiers with him. Then, another praetor called Cossinius who had been sent out with another large force to offer support to Varinius. He was almost taken prisoner by the insurgents as the gladiators caught his camp off-guard while the praetor was bathing.

Lastly, the rebels defeated Varinius and, as a symbol of his victory, Spartacus took the praetor’s horse.

Now, the gladiator army was free to raid the countryside of Italy unopposed as more and more men from the region swelled their ranks. According to Appian, Spartacus’s army boasted over 70,000 soldiers. Presumably, Oenomaus died around this time, possibly in battle, as he is no longer mentioned by historians. Spartacus and Crixus are referred to as the commanders of the rebel army.

At this point, the insurgents reached a possible crossroads in their journey, one which still divides both classical and modern scholars. According to Plutarch, Spartacus wanted to traverse the Alps and escape Roman territory. In his view, the Thracian planned to disband the army once it had secured freedom. However, Spartacus could not convince his men who were feeling cocky enough that they wanted to continue raiding. Other sources claimed that the plan was (and had always been) to march on Rome.

The notion that there was some dissension in the ranks regarding their next move was strengthened by the fact that, at one point, the rebels split into two armies – one was led by Spartacus, the other by Crixus. Whether this division was strategic so they could cover more ground or it was caused by disagreements, we cannot say with any certainty.

The Death of Crixus

By this point, the Senate realized that the little uprising caused by the escaped slaves was no laughing matter and it was only growing in power. Some have argued that the Roman leaders were reticent to unleash the true might of Rome because it would have been an admittance of defeat, in of itself. Just the idea that a few enslaved Thracians, Germans, and Gauls could threaten the Roman Republic was an embarrassment.

But after a year of the rebels running wild, the Senate had had enough. In 72 BC, it tasked two consuls, Gellius and Lentulus, to put an end to the uprising, and each one commanded a Roman legion.

The exact size of a legion actually varied throughout the history of Rome. According to Livy, during the Republic, the Senate set the size at the start of the year based on availability and circumstances. Although typically a legion contained around 4,000 infantry and a few hundred cavalry, it would vary anywhere between 3,000 and 6,000 soldiers.

Regardless of how many men the legions had, they were still vastly outnumbered by the insurgent forces. However, what they lacked in manpower, they more than made up for with strict military training and top-of-the-line equipment. Spartacus’s forces, on the other hand, consisted mostly of peasants, deserters, slaves, and shepherds. Very few of them stood a chance against a Roman soldier in combat.

Here we arrive at a bit of a contentious moment because the two main sources, Plutarch and Appian, give differing accounts on the battles between Spartacus and the consular armies. They do not necessarily contradict each other, but they each mention events that the other ignores.

As I said previously, the rebel forces split into two armies. Both historians agree that Gellius and his legion fought Crixus who commanded around 30,000 men near Mount Garganus. This encounter resulted in a decisive victory for the Romans. The rebel army lost around two thirds of its troops, including Crixus who was killed in battle. When hearing of this, Spartacus allegedly sacrificed 300 Roman soldiers in his honor.

Fighting the Consular Armies

Both sources also agree that Spartacus and the main insurgent force faced the army of Lentulus while heading for Cisalpine Gaul and triumphed. Afterwards, however, they start to differ. We have to remember that even the best sources we have for the War of Spartacus wrote their accounts over 150 years after the uprising had taken place. Many details could have been altered or forgotten.

According to Appian, Gellius and his men headed towards Spartacus after defeating Crixus. His hope was that he would reach the Spartacan army in time and trap it between the two legions commanded by him and Lentulus. He was too late, though, and the Thracian had time to best the other consul, turn his soldiers around and defeat Gellius in combat, also. The two consular legions retreated and regrouped back in Rome. They then united as a single army and made a third attempt against Spartacus at Picenum. They were defeated, once again.

Plutarch makes no mention of Spartacus’s fight against Gellius or the Battle at Picenum against both consuls. Instead, he says that, after the Thracian bested Lentulus, he engaged in combat with an army of 10,000 men led by Gaius Cassius Longinus, the governor of Cisalpine Gaul. Once again, he was victorious.

There is also some confusion regarding what happened after Spartacus defeated the consular armies. While Plutarch offers no concrete information, Appian, more or less, places Spartacus on the warpath to Rome. Maybe it was the death of Crixus, or maybe he thought himself invincible in battle, but Spartacus seemed determined to pillage mighty Rome itself. He killed all his prisoners and his pack animals and set fire to any useless materials that might have burdened and slowed him down. He marched on the capital with an army of 120,000 footmen.

Despite his gung-ho attitude, Spartacus had a change of heart on the way and realized that, perhaps, his army was not strong enough just yet. Instead, he took over the city of Thurii and the surrounding mountains and conducted raids for bronze and iron to forge weapons and equip his troops.

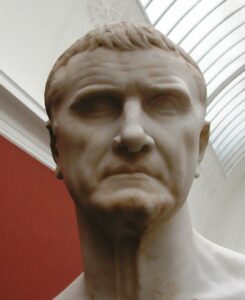

Marcus Licinius Crassus

The Senate dropped any pretense that the Spartacan rebellion was anything else than a major threat that endangered the Republic itself. It gave the task of putting down the uprising once and for all to Marcus Licinius Crassus.

Crassus is primarily remembered today for, allegedly, being the richest man in Roman history. The true extent of his wealth is impossible to gauge with accuracy, but it could have been up to $20 billion in modern currency. The number most commonly used is 200 million sestertii, an estimation provided by Pliny. Plutarch used gold talents to quantify Crassus’s wealth and placed it at over 7,100 talents which would mean, in modern terms, 213 metric tons of gold.

Crassus’s fortune came from “fire and war, making the public calamities his greatest source of revenue”, as Plutarch put it. Some of his lucrative businesses included a fire department that arrived at a burning home and only extinguished the flames if it negotiated a generous bargain with the owner. Otherwise, the men simply looked on as the home burned to the ground. Afterwards, Crassus even offered to buy the property (at a significantly-reduced price, of course).

Another one of his schemes was a school for slaves. By taking cheap, unskilled labor and giving them training, he increased their value significantly and then sold them on for a tidy profit.

The bulk of Crassus’s wealth, however, came from real estate. He was an ally of Sulla, the Roman general who prompted a Civil War that involved the aforementioned Quintus Sertorius. After his triumph, Sulla enacted proscriptions, meaning that all of his powerful enemies were either put to death or banished and their possessions confiscated and put up at auction. This allowed Crassus to purchase massive amounts of land and property for next to nothing.

Going back to the war, Crassus was not only rich, but also had high political aspirations. He knew that putting down this rebellion would secure his position in the Senate. He used his own money to equip and train new troops. He was made a praetor and was granted command of six new legions, plus what was left of the two consular armies.

The Decimation

At first, it looked like this military expedition would end like all the others. While Crassus and the bulk of his army waited for Spartacus on the borders of Picenum, he sent his legate, Mummius, with two legions to circle around and approach the rebellion army from behind. Crassus gave explicit orders not to attack the insurgents or even to engage in skirmishes. Mummius disobeyed, feeling like he had an advantageous position. He attacked and he lost.

Clearly, Crassus needed to teach some discipline, something he accomplished with an extreme measure. He revived a punishment that had not been used for almost 200 years – decimation. The soldiers were divided into decades – a decade, here, simply meaning a group of ten. They drew lots and the losing soldier from every decade was executed.

Again, there is a bit of disagreement over who Crassus decimated, exactly. Plutarch said it was only one cohort of 500 or so soldiers. Appian, however, believed it was either the two consular legions or his entire army after a defeat. This is a pretty big detail because it makes the difference between the execution of 50 soldiers, more or less, and the execution of thousands. Either way, the tactic seemed to work, and Crassus showed his men that he was “more dangerous…than the enemy”.

Victories for Both Sides

Crassus’s methods might have been harsh, but they yielded results. The following times that the armies met in battle, the Romans were victorious. Spartacus was forced to retreat to a region in southern Italy called Lucania. Plutarch reports that the Thracian planned to take over the island of Sicily and regroup there. For this, he negotiated passage with a group of Cilician pirates. However, with pirates being pirates, they double-crossed him and sailed away after being paid.

Spartacus had his back against the wall so he fell back to the peninsula of Rhegium. Crassus felt that he had victory in his grasp, but he was wise enough not to underestimate the Thracian as many had done before him. Instead of forcing a battle, he built fortifications across the isthmus to the peninsula so that the rebels would be cut off from any provisions.

Indeed, this tactic split the rebellious fighters into two groups. One of them broke through the siege and started their own raiding campaign. Crassus fell upon them swiftly and destroyed them in battle, but he was disheartened to see that their fighting spirit had not been extinguished. Although he killed over 12,000 insurgents, upon inspection, only two of them had wounds in their backs. All the others had died facing their enemy, fighting until their last breath.

Meanwhile, Crassus sent another army led by one of his officers, Quintus, to pursue the Spartacan forces which fled to the mountains. The gladiator turned his troops around and met the Romans in battle and was triumphant. Bolstered by this recent victory, the rebels wanted to take on the main army of Crassus.

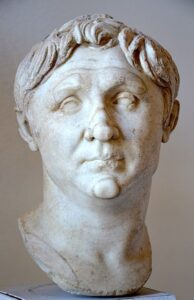

The Arrival of Pompey

One final, decisive battle suited Crassus just fine. Although at first he seemed content with weakening the insurgents as much as possible, now he was fighting against the clock as he received news that Roman reinforcements were on the way. Pompey the Great had managed to put down the Sertorian rebellion in the Iberian Peninsula and had redirected his forces to take on Spartacus. Another commander named Lucullus was also coming with additional soldiers.

You would think that the arrival of reinforcements would be good news for Crassus, but he had no intention of sharing credit with anyone for putting down the largest rebellion in Roman history. Before making his last stand, Spartacus actually tried to call a truce with Crassus, but the Roman praetor rejected it categorically. To fulfill his ambitions, nothing but the absolute obliteration of the revolt would have sufficed.

The armies met at the Battle of the Silarius River. The Spartacan troops fought hard, but were soundly defeated. Around 36,000 of them died in battle. Around 6,000 more were taken prisoner by Crassus and were all crucified along the Appian Way. About 5,000 rebels managed to flee the battle, but they were met by Pompey who cut them to pieces.

Triumph

Pompey told Rome that, even though Crassus won the battle, he “extirpated the war”. Accordingly, for this and his victory in Hispania, he was given a major triumph upon his return and made consul. In this case, a triumph is a Roman ritual which celebrates a general’s successes in battle.

Crassus was later made a censor with Pompey’s support. He also won over the masses of Rome by using his money to throw a giant feast in honor of Hercules and paying for everyone’s grain allowance for three months. The two of them later formed an informal alliance called the First Triumvirate alongside another Roman up-and-comer named Julius Caesar.

The Fate of Spartacus

It would have been nice if we could have ended with one final anecdote about Spartacus since this bio is about him, after all. Unfortunately, history is seldom that accommodating. He died in battle – killed at an unknown time by an unknown soldier – and his body was never recovered.

Even though he had no possible way of knowing this, Plutarch thought to provide a more fitting end for the Thracian who tried to bring Rome to its knees. He claimed that, during battle, Spartacus cut his way through the enemy ranks and tried to reach Crassus himself, but was stopped when two dead centurions fell upon him. He was then completely surrounded and cut down while fighting to the bitter end.