It’s one of the worst diseases in history. Smallpox spent millennia as the scourge of mankind, inflicting death wherever it reared its ugly head. In the 20th Century alone, it killed some 300 million people, almost as many as Spanish Flu. But while survivors of the Flu returned to normal, survivors of smallpox were left damaged for life. Blindness, infertility, and hideous disfigurement were frequent outcomes; ones that affected people from all segments of society. Princes, pharaohs, emperors, queens, artists, warriors, workers… all found themselves struck down by a disease that felled empires and annihilated cities.

Until, one day, it stopped. In the mid-20th Century, a push by the World Health Organization saw smallpox become the first disease to ever be completely eradicated. The last natural case was recorded in 1977. After thousands of years of suffering, humanity was finally free.

But what was this virus we drove to extinction? Where did it come from, and how did it affect the story of humanity? Today, we’re delving into the life of one of history’s great plagues… and how it created our modern world.

An Ancient Curse

Of all the nasty viruses that have afflicted mankind, few have been as nasty as smallpox. Once inhaled into your system, it stays hidden for around 12 days – almost like an army laying the perfect ambush.

In that time, your life carries on as normal. You go to work, hang out with friends, never knowing that your death warrant has already been signed. Then, on day 13, it happens. The first symptoms are headaches, back pain, chills, vomiting.

At first, you pray that you’re mistaken. That it’s just a bad dose of the flu.

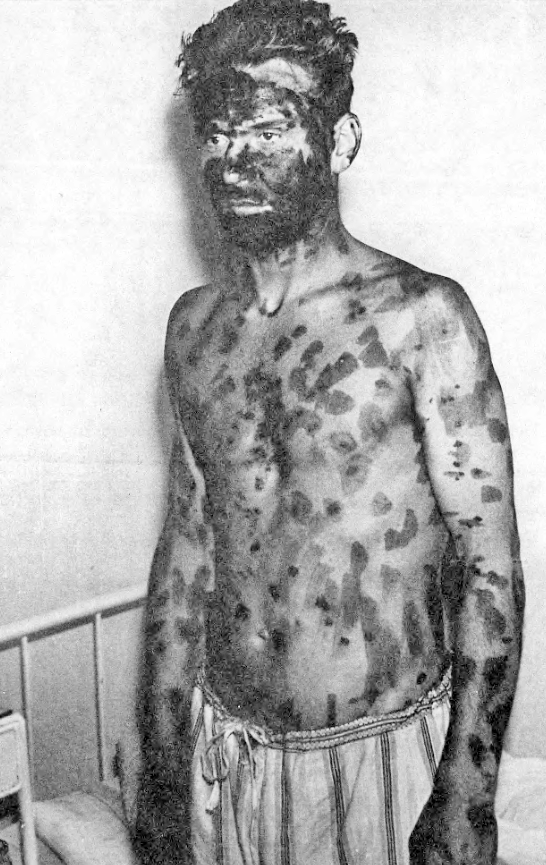

But, as the 17th day approaches, you discover the awful truth. Pustules start to appear inside your throat, then spread out like an army marching across your skin. Every inch of you this army touches breaks out in a hard, pus-filled lump with an indentation in the middle.

After that, you’re on a rollercoaster of pain.

Depending on which version of the virus you’ve caught – Variola minor or Variola major – your chances of death could be anywhere from a mere three percent, to a staggering 30 percent. But surviving might be even worse. Once smallpox has finished ravaging your system, the pustules on your face, feet, and hands scab over and fall off, leaving behind hideous, pitted scars that will stay with you for life.

Even once you recover, you may be left blind and infertile.

Sounds awful, right? Almost as if a writer with a particularly twisted imagination sat down and tried to dream up the nastiest science fiction disease they could. But smallpox isn’t science fiction. It existed during the lifetime of anyone in their mid-forties or older.

And prior to that, it had been around for centuries.

The exact origins of smallpox are a mystery. Some have suggested it may date back as far as 10,000 BC; when the Neolithic Revolution brought us into sustained contact with livestock.

On the other hand, research in 2016 concluded it may have appeared as late as the sixteen century AD.

For this video, though, we’re just going to go with the majority opinion, which says all we know is that smallpox had appeared by 1570 BC.

That’s because 1570 BC is the start date of Egypt’s New Kingdom, and a handful of mummies from the era still show telltale signs of infection. This includes Rameses V, who has a swathe of long-dead pustules dried out on his cheeks. Likely the first-known instance of smallpox killing a leader.

Not that most victims were anybody you’d have heard about.

Although smallpox afflicted adults, the majority of those it killed were children. And the majority of those were kids who lived in cramped quarters were the virus could spread.

And spread it did. Although smallpox was relatively non-contagious compared to stuff like measles; once it got hold, it really got hold.

There’s a 14th century BC Hittite tablet describing what may be the disease sweeping their lands. The pandemic raged for twenty years and carried off two rulers before finally fading. But if that sounds bad, just know there is far worse to come. Across the history of Eurasia, there would barely be a single empire that didn’t come into contact with smallpox at some point or another.

In some cases, this brief brush would be enough to bring their civilization crashing down.

The Fall of Empires

If you ever find yourself in possession of a time machine, be sure to follow our advice.

Whatever you do, do not set the controls for 430 BC Athens. That’s because Athens in 430 BC was in the grip of a pandemic that would make CoVid-19 look like an outbreak of rainbows and puppies.

During the second year of the Peloponnesian War, a disease arrived in the port of Piraeus.

Known as the Plague of Athens, it killed around a third of the population in horrifying fashion. The historian Thucydides – who himself contracted the virus – described it thus:

“Violent heats in the head; redness and inflammation of the eyes; throat and tongue quickly suffused with blood; breath became unnatural and fetid; sneezing and hoarseness; violent cough, vomiting; retching; violent convulsions; the body externally not so hot to the touch, nor yet pale; a livid color inkling to red; breaking out in pustules and ulcers.”

Pustules and ulcers. Sound familiar?

We don’t actually know what caused the Plague of Athens, but smallpox is a major contender; alongside measles and Bubonic plague. Especially when you read that many survivors were left blind.

Whatever it was, the Plague left Athens badly weakened. It carried off the great leader Pericles, and contributed to Athens ultimately losing the Peloponnesian War.

But while the jury is out on whether smallpox was the culprit, the same can’t be said of one of the ancient world’s other great plagues. The Antonine Plague landed nearly six centuries after the Plague of Athens, arriving in Ancient Rome around 165 AD.

In all likelihood, it was brought from China, traveling along the Silk Road; carried into Europe by the very traders trying to escape it. Where the Plague of Athens would kill tens of thousands, though, the Antonine Plague would kill millions.

Two weeks after contact with an infected person, the victims would come down with fevers, diarrhea, vomiting, coughing.

Shortly after that, their skin erupted in pustules which soon formed scabs that covered nearly the entire skin. And if you think that sounds gross, wait till you hear this: the worst affected would even cough up scabs that had formed inside their bodies.

Yuck.

At the plague’s height, over 2,000 people were dying each day in the Eternal City; a number that eventually included Emperor Marcus Aurelius. The final death toll was a staggering 3.5 to 7 million. It may have contributed to the military’s inability to defend Rome’s German border.

Naturally, people had all sorts of wacky theories about its cause.

Some said a Roman general opened a forbidden door while sacking Seleucia, releasing the plague. Others that a soldier opened a casket in Babylon’s temple, and the Gods sent the plague as punishment. It’s only with hindsight that we can call the Antonine Plague what it most likely was: Smallpox.

Yet while smallpox devastated Eurasia’s early empires, it also gave them a strange kind of gift.

With each new pandemic, Eurasian resistance to the pox grew. While that might not sound so great, it would soon become a valuable asset. Some 1400 years after the Antonine Plague, a group of Europeans would arrive on a continent that had never seen smallpox before.

It would be thanks to this tiny virus that they soon became that continent’s masters.

From the New World

The next few centuries were an era of migration for smallpox.

At some point before the 6th Century, the virus got its tendrils into India and China, where cults devoted to smallpox deities sprang up.

By the 6th Century, it had reached Japan; alongside the weird, cross-cultural belief that it could be stopped by the color red. Come the 11th Century, the Crusades spread the disease far and wide, afflicting corners of Europe that had never been hit before.

Not long after, Portuguese colonists were introducing it to parts of Africa, making smallpox a truly global scourge. But the biggest, most-dramatic migration came in the early 16th Century.

A decade or so after Columbus discovered it, smallpox finally set foot in the New World.

By now, it was more feared in Europe than even the Black Death. Yet it was destined to give the Europeans a helping hand. In 1520, a ship carrying someone infected with smallpox – often said to be a slave – landed on the shores of Mexico. This was the year of Hernan Cortez’s expedition into Mesoamerica’s heartland, into the Aztec Empire.

As the Europeans marched on, the pox trailed in their wake.

It wasn’t long before it was wreaking havoc. Smallpox was unlike anything the indigenous peoples’ immune systems had ever encountered before. It overwhelmed them. Devastated them.

If smallpox was a nightmare for Europe, then for Mesoamerica it was nothing short of the apocalypse. That October, 1520, smallpox ravaged the great Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan.

Up to 40 percent of the population died. As the Aztecs recorded it:

“The plague lasted for 70 days, striking everywhere in the city and killing a vast number of our people. Sores erupted on our faces, our breasts, our bellies; we were covered with agonizing sores from head to foot.”

The Europeans were more detached:

“As the Indians did not know the remedy of the disease,” wrote one of Cortez’s team, “they died in heaps, like bedbugs.”

However you look at it, smallpox was devastating for the Aztecs. When Cortez conquered Tenochtitlan in 1521, it was in large part because European germs had already killed so many of its citizens.

Nor would the Aztec Empire be the only one torn down by the virus. In the Andes, smallpox arrived ahead of the Europeans.

In 1528, the Incan ruler, Wayna Qhapaq, was carried off by it.

His death sparked a civil war between his two heirs that helped spread smallpox across the Inca lands. In some places, it killed between 65 and 90 percent of the population.

By the time Francisco Pizarro arrived in 1532, the empire was barely clinging on. Pizarro just delivered the killing blow. But it wasn’t just in South America that smallpox made its presence felt. Not just below the border where it changed history.

Up in the north, the colonists would even find a despicable use for it.

Blankets and Bullets

Contrary to what you may have heard, smallpox wasn’t deliberately introduced into the Native American population by colonists.

In fact, it had already swept the Americas like wildfire, passing from indigenous group to indigenous group like a really crappy game of pass the parcel where every single prize is over half your population dying horribly.

The year before the Mayflower arrived, an epidemic in what is now New England killed up to 90% of the locals.

Yet even if the colonists weren’t standing outside their cabins, cheerfully handing out infected blankets, they were still on the pox’s side. When an outbreak hit Massachusetts in 1633, plenty of Puritans believed the grim Native death toll was a gift from God.

But let’s back up a moment and discuss those blankets.

There’s a good chance you clicked on this video expecting to hear tales of colonists deliberately giving smallpox to Natives. It’s one of the iconic images in the giant picture book titled How the Native Americans Got Screwed Over.

Despite its vast reputation, though, this scene only played out a single time. The year was 1763, the last year of the French and Indian War.

That spring, Shawnee and Mingo warriors laid siege to Fort Pitt, in what is now Pittsburgh.

Smallpox was already inside the fort, and the commander wrote to his superiors, worrying it would spread. So his superior wrote back saying why left all that good smallpox go to waste? Across two letters, Sir Jeffery Amherst, commander in chief of the British forces in North America, wrote:

“Could it not be contrived to Send the Small Pox among those Disaffected Tribes of Indians? We must, on this occasion, Use Every Stratagem in our power to Reduce them… try Every other method that can serve to Extirpate this Execreble [sic] Race.”

Interestingly, we don’t know if Amherst’s instructions were actually followed.

What we do know is that a militia captain at the fort – one William Trent – had already tried giving diplomats from the attacking tribes a couple of blankets infected with the pox.

And that was it. The one documented time that colonists tried to deliberately give Native Americans smallpox.

To be brutally honest, it probably didn’t make a difference.

Smallpox was already in the Native American population. There were already major outbreaks happening around Fort Pitt.

The moment European germs touched America’s shores, the Natives were already doomed. But while it had been Europeans who spread smallpox to the New World, it would also be a European who finally stopped it in its tracks.

It’s time to meet Edward Jenner.

“The Greatest Gift of Our Time”

By the time the 18th Century rolled around, smallpox had become a gross fact of life.

In Europe alone, it killed 400,000 people a year, including some at the very top of society. Peter II of Russia, Mary II of England, and Louis XV of France were all carried away by the disease. It had also acquired its name. “Smallpox” was meant to differentiate it from the “great pox”, or what we’d now call syphilis.

Yet even as Europe suffered, other continents were already bringing smallpox under control.

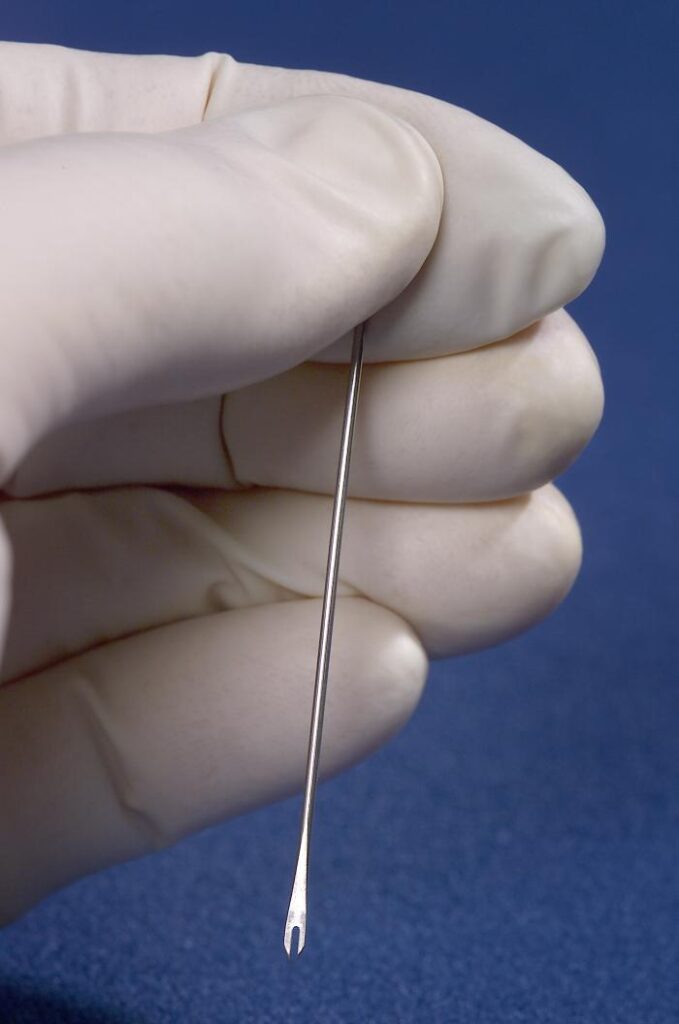

Variolation is thought to have started in 10th Century China and India, before spreading west, into the Ottoman Empire.

The process was as low-tech as it was barf-inducing.

Basically, you’d take the pus of someone infected with smallpox, then make a load of cuts in the arm of a healthy person and insert the pus inside them.

A couple of weeks later, the healthy person would come down with a mild case of smallpox, recover, and have lifelong immunity.

Broadly speaking, this worked. While the normal risk of death with smallpox was around 30%, only around 0.5% died from variolation. But the method wasn’t perfect. Although variolated people rarely died, they were infectious. They could easily pass on a much more serious case to those around them.

It also required you to have a constant supply of patients with smallpox, whose pus you could take and insert into healthy people. So, great as variolation was compared to just, y’know, dying of smallpox; it could still be improved.

Luckily, someone was about to do just that.

Edward Jenner was a surgeon living in Gloucestershire, a bucolic slice of England famed for its dairy industry.

It was also famed for its cowpox – a virus that tended to affect the hands of milkmaids, leaving their fingers covered in unsightly pustules. But here’s the thing. None of these cowpox infected milkmaids ever seemed to catch smallpox.

The popular version of this story is that Jenner was the first person to notice this, but that’s not true.

Pretty much all the locals were aware cowpox meant no smallpox. A farmer called Benjamin Jesty had even used cowpox material to deliberately innoculate his sons against smallpox in 1774, but then forgotten to tell anyone about his world-changing breakthrough.

So it was left to Jenner to discover it independently.

In 1796, Jenner asked a family he knew if he could borrow their 8-year old son – James Phipps.

He then took some cowpox pus from a milkmaid named Sarah Nelmes and inserted it into Phipps’s skin. After Phipps had recovered from a mild case of cowpox, Jenner then exposed the boy to smallpox. Repeatedly. But nothing happened.

James Phipps was immune to the virus.

Today, hearing that story mostly makes us think “Holy crap, that dude literally tried to give a child smallpox. What the Hell, olden times?”

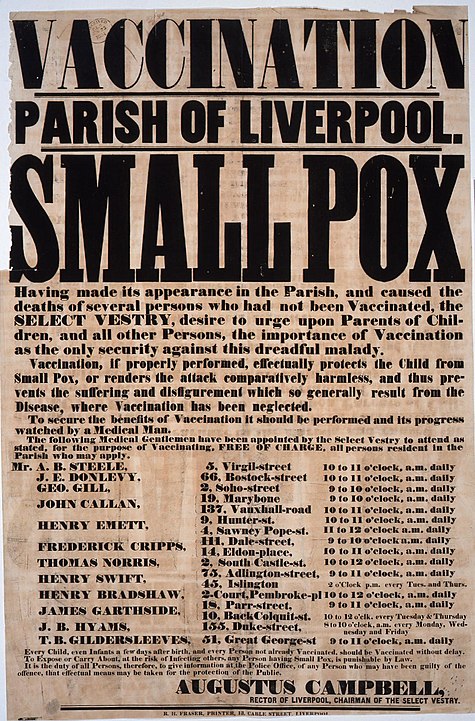

But make no mistake. This was a breakthrough that put variolation to shame. Jenner named his new technique “vaccination”, after the Latin for cow.

Barely had he coined the term than the first anti-vaxxers came crawling out the woodwork. The Royal Society told Jenner he shouldn’t “promulgate such a wild idea if he valued his reputation”.

Yet promulgate Jenner did. In his 1798 treatise on vaccination, he declared:

“the annihilation of the smallpox, the most dreadful scourge of the human species, must be the final result of this practice.”

His words landed like a bomb.

Napoleon called vaccination “the greatest gift of our time”. Thomas Jefferson told Jenner “mankind can never forget that you have lived.” By 1810, both Bavaria and Denmark had made vaccination mandatory. In the following decades, the vaccination slowly spread around the globe.

But Jenner’s dream of a world without smallpox would never materialize. Even as cases plunged, the virus still stubbornly clung on. Still ruined lives, even as the 20th Century reached its mid-point.

But not for much longer.

The Disease Defeated

By the beginning of the Cold War, much of the West had already defeated smallpox. The last US case was in 1949. Three years later, North America was declared smallpox free. A year after that, Europe followed suit.

But even as parts of the world defeated the virus, others were still in its lethal grip.

As late as 1967, there were still some 10 to 15 million smallpox cases globally, with parts of Latin America, Africa, and Asia hit badly.

But 1967 was also smallpox’s last hurrah. That same year, the World Health Organization – or WHO – announced a plan to eradicate it completely. It was an immediate, unqualified success. The speed at which smallpox was brought to heel seems dizzying today. By 1971 – just four years after the program began – it had been eradicated in Latin America.

This success was due to new techniques that emphasized contract tracing and mass vaccination; and new tech that included a freeze-dried, heat-stable virus to use in vaccinations.

In late 1975, the final case was reported in Asia.

Rahima Banu was a three year old girl living in Bangladesh when she contracted Variola major.

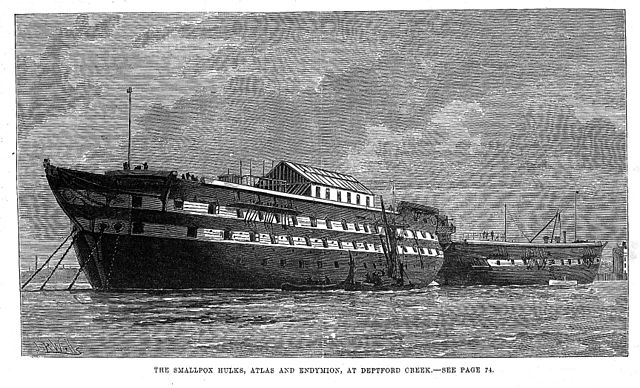

A local 8-year old reported her to the WHO, who responded with a massive lockdown.

Rahima Banu was isolated at home under 24 hour surveillance. Every household within 2.5km was mass-vaccinated; and every public space within 8km disinfected. It sounds like overkill, but it worked. When Banu recovered, variola major was dead in the wild. Two years later, variola minor struck for the last time.

Ali Maow Maalin was a hospital worker in Somalia, tasked with looking after Africa’s last smallpox patients.

On October 22, 1977, he himself came down with the disease and was quarantined. He recovered that November, and that was it for smallpox in Africa. But the last ever case of smallpox in human history wouldn’t happen in rural Bangladesh, or out in Somalia.

It would happen in England.

The summer of 1978, hospital photographer Janet Parker began suffering a headache and bad muscle pain. Shortly after, red welts appeared across her body. Stumped, her doctors tried all sorts of diagnoses.

It wasn’t until she’d been ill for two weeks that someone realized it was smallpox.

By then, it was too late.

On September 11, 1978, Janet Parker became the last person in history to die from smallpox. Although smallpox wouldn’t kill anyone else in Birmingham, the tragedy still claimed additional victims.

The sight of Parker covered in pustules caused her father to have a fatal heart attack. When the source of the outbreak was traced to a lab in the university building Parker worked in, the head of the microbiology department slit his own throat.

Finally, on May 8, 1980, the WHO declared the planet smallpox free. After millennia of terror, humanity’s worst plague had been defeated.

Today, the disease exists only in two carefully guarded labs – one in Atlanta, and one in Siberia. Critics say these last samples should be destroyed, lest they escape into the wild. But supporters say the samples may one day become necessary – like if a new strain of pox similar to smallpox evolves naturally.

But rather than focusing on the negatives, let’s end this video on a high note.

For three decades, smallpox stood alone as an anomaly, the only disease in history we’d ever managed to eradicate.

Then, in 2011, it was joined by another.

Bovine Rinderpest was called “the measles of cattle,” killing entire herds until we finally managed to stamp it out – we like to think as a late ‘thank you’ present to cows for cowpox.

And Rinderpest may not be the last.

Currently, Guinea Worm is the target of an intense eradication campaign. When the program started in 1986, there were over 3.5 million cases a year.

In 2019, there were fewer than 60.

The story of smallpox, then, is both a terrifying story of death and destruction… but also one of hope.

For the first time ever, in the face of a disease almost as old as civilization itself, humankind was able to come together and not just combat it, but wipe it out. Barring an accident at one of those labs, no-one will ever again know the pain of losing someone to smallpox.

While CoVid-19 has showed us that disease is still something humanity has to fear, the eradication of smallpox is evidence that we really can overcome it. Given enough cooperation, given enough funding, it really is possible to rid the world of a monster.

Smallpox’s tale may have lasted millennia and cost millions of lives, but it is now finally over. The last chapter has ended.

And this time, happily, there won’t be a sequel.

Sources:

History, the Rise and Fall of smallpox: https://www.history.com/news/the-rise-and-fall-of-smallpox

Britannica: https://www.britannica.com/science/smallpox

CDC: https://www.cdc.gov/smallpox/history/history.html

Timeline: https://www.cdc.gov/smallpox/history/smallpox-origin.html

Edward Jenner: https://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/empire_seapower/smallpox_01.shtml

In Our Time on inoculation: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p003c19q

Cowpox or horsepox? https://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/mysterious-origins-smallpox-vaccine-180970069/

Smallpox and the Aztecs: https://theconversation.com/how-smallpox-devastated-the-aztecs-and-helped-spain-conquer-an-american-civilization-500-years-ago-111579

Fall of the Inca Empire: https://www.ancient.eu/article/915/pizarro–the-fall-of-the-inca-empire/

Smallpox and Native Americans: https://books.google.cz/books?id=v0zEiM_hijsC&pg=PA26&lpg=PA26&dq=1633+smallpox+epidemic&source=bl&ots=z6tmAw2L4q&sig=ACfU3U3sOq2q72GGdEBYXdoRuYMYsoQXEw&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwjpp5m52tHpAhUYHcAKHa93DFoQ6AEwDnoECAcQAQ#v=onepage&q=1633%20smallpox%20epidemic&f=false

Infected blankets: https://www.history.com/news/colonists-native-americans-smallpox-blankets

Smallpox in labs today: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20140130-last-refuge-of-an-ultimate-killer

Some notes on vaccination: https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(10)60689-7/fulltext

Antonine Plague: https://www.ancient.eu/Antonine_Plague/

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/what-rome-learned-deadly-antonine-plague-165-d-180974758/

Plague of Athens: https://www.ancient.eu/article/939/the-plague-at-athens-430-427-bce/

Smallpox in the Hittite Empire: https://books.google.cz/books?id=z2zMKsc1Sn0C&pg=PA16&lpg=PA16&dq=hittite+tablets+smallpox&source=bl&ots=-f2gtPvtk_&sig=ACfU3U1zwDDda1xc4MqvULXCR-ttJtHBHg&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwiBmbDHqdHpAhWOQUEAHVwyDFkQ6AEwAHoECAgQAQ#v=onepage&q=hittite%20tablets%20smallpox&f=false

Does smallpox actually only date from the 16th Century? https://www.nationalgeographic.com/news/2016/12/mummies-smallpox-virus-dna-lithuania-health-science/

1978 Birmingham outbreak: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-birmingham-45101091

Notes on wiping out Guinea Worm: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-02921-w

Notes on malaria eradication: https://www.vox.com/future-perfect/2019/9/10/20857132/malaria-eradication-2050-gene-drive-lancet-study