It’s a rare work of art that comes to represent the entire movement that birthed it: Monet’s Water Lillies and Impressionism, for example, or Millai’s Ophelia and the Pre-Raphaelites. In today’s case, nothing represents Surrealism quite like the image of a melting clock, and no artist better encapsulates the feel of Surrealism more than Salvador Dali.

If you know nothing about art — if you grew up inside that compound from The Village and have never even seen pencil put to paper — you know that melting clocks probably mean things are about to get weird. One of the most referenced images in the modern canon, inspiring jokes in everything from The Simpsons to Looney Tunes, The Persistence of Memory is the brainchild of none other than our boy Salvador, the genre-defining multi-media artist best known for living a life that was almost as weird as the subjects he painted.

Depending on the source, the melting clock represents either the impermanence of time, or the melting of cheese. It’s a deeply ironic image, but the greater irony lies in the fact that, during his life, the man who would come to represent Surrealism found himself kicked out of the movement by the very friends and colleagues who rose to fame with him.

Portrait of the Young Artist as a Portrait Artist

Born in 1904 to a middle class family, Dali began painting early, showing a formidable command of Impressionism, and had his first public gallery show at the age of 14. He was, by all accounts, a shy and introverted child, who spent much of his time playing around the rocky coast of Cadaqués, in Spain. It was a favorite vacation spot for his family, and the eventual site of his first and best-loved house.

While he and his sister were close, both of them often felt overshadowed by the ghost of their parents first child, who died at the age of 2 shortly before Dali’s birth. He would later paint a portrait of his brother, and often described him as “the first version of myself, but conceived too much in the absolute.”

It’s impossible to overstate the impact Cadaqués had on Dali’s development as an artist. The alien, rocky shores visible on so many of his canvasses, the washed-out beaches populated by lone bathers, all of these trace back to the days he spent wandering around the tide pools, gazing in awe and horror at the full mystery of undersea life, amorphous jellyfish and radial sea urchins which he and his father loved to eat.

The figure of the sleeping head, referred to as The Great Masturbator, is rumored to have been inspired by one specific fallen boulder, arched like a kidney bean and pitted with a spongelike array of holes. One can easily envision a young Dali staring at this rock, imagining it some fantastical monster cowering over in the fetal position. Maybe he imagined it as himself, hiding from his father’s wrath.

Even during his youth, their relationship was rocky. His father’s stringent discipline was softened by his mother’s dutiful coddling, though she died when he was only 16. He described it as “the greatest blow I had experienced in my life.” His father married his mother’s sister barely a year later, but this relationship did not seem to trouble Dali.

As disagreeable as they might have been, Dali’s father was an ardent supporter of his son’s artistic development, paying for books of Impressionist paintings and personal tutors. He even went so far as to arrange a gallery showing for his 17 year old son. The location was the Municipal Theater in Figueres, which would later become the Dali Theater and Museum, the very building he would eventually die in.

If Dali ever remarked upon the irony of dying in the place which birthed him as an artist, it was never recorded. As it would eventually be Dali’s controversial art which drove them apart, one must wonder if his father ever regretted supporting his creative endeavors in the first place.

So much drama and strife, birthed from a single act of support! Let this be a lesson to the fathers listening today: Never support your children, lest they become the next Salvadore Dali.

The Art of Confidence

In college, Salvador Dali studied at the San Fernando Royal Academy of Fine Arts. There, he made friends with artists like Luis Buñuel and Frederico Garcia Lorca, the latter of whom held a deep and unrequited passion for the Dali.

Now, it’s easy to start from the popular image of adult Dali as an exuberant anteater-owning weirdo and simply make it smaller to represent youth, but he was actually quite shy in school. Among his friends he was considered to be bad with girls, a trait which would very much resolve itself with sufficient fame.

He and his friends studied the art movements emerging in Barcelona and Paris, as well as the new and controversial theories of academics like Freud. Dali would go on to paint some of the first Cubist works ever produced in Madrid, starting with the geometric Cabaret Scene. Though it often takes over a thousand words to describe a picture, it’s easy to say this one like if Keith Harring did the cover art for a smooth jazz album sold exclusively at Starbucks.

After accusing his professors of being unqualified to judge him, he dropped out shortly before his final exams in 1926. Normally, that kind of stunt lands you in a factory sewing belt buckles onto hats. But when you’re already friends with Pablo Picasso, all that was left for Dali to do was to grow a mustache and start blowing people’s minds.

The Secret To Good Art Is Artistry

By the time he failed to graduate, Dali had already cultivated an image of an eccentric dandy, dressing in stockings and knee-breeches, like he was a lesser aristocrat waiting in line at the guillotine. It’s somewhat refreshing to know that art school kids remain unchanged across history and geography, with the notable exception that the weirdly dressed art school dropouts you know never went on to become Salvador Dali. His secret, and in fact, the unspoken rule across all artistic pursuits, is that you can get away with being a weird, pretentious dork as long as your work is very, very good.

In all accounts, young Dali’s work is that good. His absolute mastery of representationalism can be seen in Basket of Bread 1926, where he managed to lend an air of stark drama to a painting of a few slices of buttered bread. That painting is over 90 years old, and it’s still fresher than anything served at the Olive Garden. One almost gets the sense that he is mocking his teachers and peers, showing off by putting so much effort into such a simple scene. It sounds ridiculous to say that an oil painting of bread feels sarcastic if you look at it too long, but just try it. Look at it too long. Tell me if it doesn’t eventually feel insulting, how accurately this bread is painted.

A common criticism of modern art is that it’s deliberately weird and incomprehensible to cover for a lack of foundational skills, and to be fair, it often is. For every actually talented eccentric, there’s twenty Piero Manzonis pooping into a can and daring you to buy it. Dali was not this. He was a popular, charismatic young fellow who knew the breadth of his skills and pushed himself beyond what his conscious mind could envision.

Paranoia and Friends

To that end, he studied Freud heavily, seeking to unleash the full weight of his creative forces from the shackles of formal logic. At that time, the surrealist movement was lost in a directionless mire, preoccupied with automatic processes of creation, and to this mix Dali added his Paranoiac-Critical method.

By focusing on abstract threats to the person in order to induce a paranoid state, Dali was able to draw up fantastical images from the deepest recesses of his mind, delivering “hand-painted dream photographs” by filtering the real world through that lens of absolute paranoia. In much the same way that humans see faces in toast or wood grain, Dali could envision armies of ants, giant eggs, elephants with impossibly stretched limbs, and bulbous protrusions of flesh held up by crutches.

This period is marked by the frequently recycled image of a child and parent on the coastline, one inspired by a childhood photo of Dali himself. Where human figures are depicted, they are small and face away from the viewer. Geometric shapes stack piled atop each other in defiance of balance and gravity, early works like The First Days of Spring and Apparatus and Hand show the clear influence of his contemporary and friend Yves Tanguy, whose art also heavily features indecipherable objects and vague, rocky coasts. Yves was also known for eating live spiders at parties. Earning a reputation as an artist has never been easy.

According to the niece of Yves Tanguy, Dali once said to her “I pinched everything from your uncle Yves.” Of course, being part of an artistic movement means influencing and being influenced by others in turn. If it wasn’t for his early studies of Cubism, Dali wouldn’t have been inspired to experiment with form, is he a plagiarist for borrowing the techniques of his friend Picasso? Would Dali have been Dali had he not drawn from the influences he did?

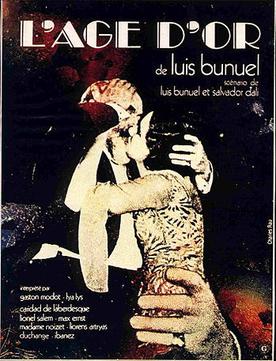

During the debut of a film Dali wrote, Age of Gold, the right-wing radical group League of Patriots disrupted the screening, attacked the audience, and smashed artworks by Yves and other collaborators, decrying the film and Surrealism in general as a poison designed to corrupt the people. The Surrealists responded to this criticism, as all great artists do, by getting much weirder.

Dali’s fascination with Freud took the forefront. As his reputation grew, he found himself liberated to commit his illicit desires to canvass, drawing nude forms tortured beyond recognition. Sex became a curious kind of obsession, something he could have gained very easily which yet was denied through a complex web of invisible hangups.

Maybe he hoped if he delved deep enough into his own subconscious, he could find the source of those hangups and allow himself to pursue his desires, rather than exorcise them upon the canvas. Thankfully for us, he didn’t!

Time Keeps On Slippin’

Indulge me for a moment in a bit of postmodern analysis, for it seems irresponsible to talk about an artist without talking about his art.

As you’re probably aware, it depicts a number of soft, melting watches, draped over a variety of shapes such as a tree, sleeping figure, and odd rectangular protrusion. The background is just a distant coastline, complete with shadowy Cadaqués cliffs.

It’s easy to read the soft watches as a commentary on the malleable nature of time, given Dali’s public appreciation of Einstein’s theories. Lacking rigidity and internal structure, devoured by a thousand tiny ants, the ultimate symbol of structure and order finds itself besieged by the forces of decay.

Of course, Dali denied all that, saying instead the image was a surrealist interpretation of runny Camembert cheese he saw at a picnic. The man loved food! He even wrote a cookbook, which has recently been reissued. In addition to being both large and expensive, many of the recipes are deliberately difficult to prepare and assemble.

Either way, The melting clock is a motif he would revisit decades later, during his Nuclear Mysticism phase, in The Disintegration of The Persistence of Memory, where the previously solid shapes have been replaced with a matrix of smaller cubes, referencing the empty space between atoms. Even the ocean in the background finds itself peeled upwards like a pancake mid-flip.

The realization that everything solid is made up of empty space clearly held a place of prominence in Dali’s mind. The trees in Disintegration are marked by prominent gaps in their own continuity. Everything coherent has been replaced by a grid of tiny versions of themselves, a perfect approximation of atomic representationalism.

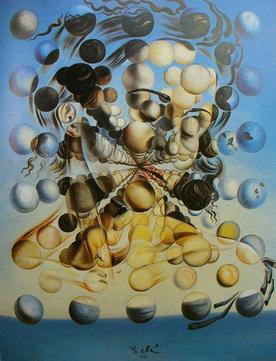

What subconscious desire was to Dali’s old work, atoms were to the Nuclear Mysticism phase. One prominent example, Galatea of the Spheres, features a deep field of orbs which resemble, when taken as a whole, a bust of his muse Gala. The spheres themselves seem to whirl and dance across the canvass, recalling how hair moves in wind, or electrons spin around a nucleus.

If you asked him, Dali would have denied the existence of any messages in his work. In the Dick Cavette interview where he unleashed an anteater on the host, he answered that the melting clock had “no meaning,” that his paintings were “hypnogogical images” drawn from the subconscious five minutes before waking.

That conflicts with the theories of Freud, which would posit a great deal of meaning in the sometimes graphically sexual imagery Dali used in his work, like the condom-shod loaf in Catalan Bread, complete with a lovingly draped melting clock.

Obviously, it’s a phallic representation. But the point of Surrealism is that what an object represents is not fixed, a rotting donkey can mean sexual excitement if you happen to be a swarm of flies. When Dali once famously asked at a restaurant, “When I order lobster, why do you not bring me a telephone?” He wasn’t just being precious, he was asking us to evaluate our assumptions about the meaning of images. What authority gets to define the significance of a melting clock? Or a randy loaf of bread?

The point of Surrealism is to bring forth a solid dream into the waking world, and what authority assigns meaning to dreams? Dali explained that to him, the crutch symbolizes impotence, that it supports softness which cannot stand on its own. But to someone with one leg, a crutch might represent the difference between helplessness and agency. Is that interpretation less valid because it disagrees with the artist?

Dali & His Muse

It’s in 1929 that Dali’s upward trajectory becomes undeniable, namely through meeting his future wife, manager, and co-conspirator, Gala Diakonova. Already married to Paul Éluard, a poet and co-founder of the Surrealist movement which gave Dali his signature flair, Gala was everything Dali was not. Confident in her body and sexually accomplished, a passionate affair soon arose between the two, and Gala’s marriage to Paul ended shortly thereafter. Womp womp!

The nature of their physical relationship remains an issue of discussion- for perverts. Dali was known to say that Gala was the only woman he made proper love to throughout his entire life. Maybe a lifelong predilection with Catholicism prevented an exploration of his natural instincts; either way, neither of them were content with a vanilla sex life.

They were both unfaithful to each other, in an oddly inclusive sort of way. He would watch her with other lovers, pleasuring himself. Other times, Dali would indulge in dalliances with his models and hangers-on, by pleasuring himself. The circle of admirers they cultivated prized ambiguity and androgyny, seeking a beauty unchained by social expectations of physiology. When it came to choosing dance partners, Gala had her pick of the ball.

Things Get Out of Hand

During the artistic process, Dali would frequently masturbate over his subjects, a habit which would later prove problematic. Gala maintained the occasional tryst, though both were discrete in their indiscretions. Dali joined at least one of his proteges in a “spiritual marriage” on a mountaintop, and Gala managed an affair in her mid 70s to the singer who played Jesus in Jesus Christ Superstar. Dali, bombastic in his Catholicism, could only have been thrilled.

Dali treated controversy as just another color on his palette. During one of his first public speeches as part of the surrealist group, he insulted the audience and Catalonia as a whole. During a later presentation, he arrived wearing a full diving suit, and almost suffocated. He was only freed when a companion found a wrench outside and detached the helmet. In his defense, Dali claimed he wanted to show he was fully submerged in the subconscious.

Controversy was no stranger to his home life, either. His parents were skeptical of his relationship with Gala, who was 10 years older and abandoned a husband and child to be with him. While his connection to his father had never been particularly stable, Dali found himself excised from the family after producing a painting which was an outline of Jesus, into which were written the words “Sometimes, I spit for fun on my mother’s portrait.”

His father never forgave him after that. Despite living within sight of each other, none of Dali’s family ever visited the house he shared with Gala. The loss of his sister was an especially deep wound.

Image and Artist

If it’s not yet clear, Dali is not a reliable authority on the subject of Dali. Being such a keen expert of self-promotion, he used every interview as an opportunity to sell a vision of himself as the artist-genius. For example, he probably never spat on his mother’s portrait for any reason. He denied supporting Hitler even as he included his face in major works.

He never clearly denounced Fascism, and instead described himself as a monarchist-anarchist. In his system, the king should rule absolutely, under which the people could enjoy the freedom of absolute anarchy. Is that contradictory? Of course. It’s Salvador Dali — why would you expect trenchant political commentary from the madman who glued a lobster to a telephone and sold it for a million dollars?

It’s also exactly the sort of philosophy which would appeal to the debauched ultra-rich, used to experiencing life as an extended orgy, so expect a revival of Monarchist-Anarchism on Goop any day now.

When the other surrealists dragged him before a kangaroo court and accused him of fascist sympathies, he feigned illness and showed up wearing too many sweaters. He would pause his self-defense to take his own temperature, shed layers, don or doff socks, do whatever it took to highlight the farcical nature of these proceedings.

His politics remain a major point of contention for both fans and detractors. Fascism would have interrupted his ability to enjoy himself, so it’s easy to read his comments insincerely. Maybe they were proto-trolling, saying the opposite of what his lefty friends were saying just to get attention. However, later in life, Dali would voice support for General Francisco Franco, the brutal Spanish dictator, calling him “the only intelligent man in politics.”

When he said this, Franco was busy killing two hundred thousand of his own citizens while imprisoning five hundred thousand more. That’s not even defensible as satire. Pablo Picasso turned his back on Dali and refused to speak of him again. The Surrealists issued a pamphlet denouncing Dali, and he became a persona non grata in the movement.

An epic troll, indeed.

Things Get Weirder

Curiously enough, his most controversial act is one you’re least likely to hear about. As we mentioned, Dali had unconventional sexual practices. Being rich and famous, he had no shortage of willing partners, with one tragically notable exception.

In 1945, Dali was introduced to the model Constance Webb by a mutual acquaintance, and he was instantly charmed. She agreed to model for him, providing inspiration for some figures in the film Spellbound. She described him as a “perfect gentlemen” during their sessions together, slowly coaxing her into working with less and less clothing.

After their final session, however, as she was relaxing with her arm over her eyes, he jumped upon her stomach and ejaculated upon her breasts, which he began licking up. She quit modeling for him immediately afterwards, only divulging the fact of her assault in interviews after the artists’ death.

This wasn’t even his first time crossing that kind of physical line. As a young man, a woman complimented his beautiful feet, so he responded by trampling her and only stopped when his friends pulled him off of her.

If there was a MeToo movement in the 40s, maybe Dali would be remembered differently. Instead, he’s much more likely to be rebuked for selling out, as if the greatest moral failing of his life were the advertising campaigns for things like leg-ware and lollipops. He was the one who designed the current Chupa Chups logo, and even insisted on displaying the logo at the top of the pop, to ensure that it’s correctly represented.

Salvadore C.K.

The question of separating the art from the artist is ultimately one of measuring exactly how much misery we’re willing to tolerate from creators in exchange for entertainment. The justification being that this sort of abuse is the price of genius, rather than the side effect of privilege. Or maybe we all just want to believe that we can get good enough at something that the laws of society no longer apply. Either way, there’s no better place to be an inscrutable genius than the United States, so off he went!

After moving to America to escape the second World War, Dali found great success in New York, but this proved insufficient to satisfy his hunger for fame. He had his eyes set on Hollywood. Having already made a name for himself in cinema circles with the famous eye-slitting scene from his first movie, Un Chien Andalou (An Andalusian Dog), it was easy for Dali to meet people who could open doors for him. He was welcomed to California with open arms, eyes, and wallets.

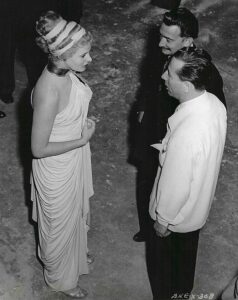

After painting a few portraits for rich well-connected socialites, he was introduced to Alfred Hitchcock, who enlisted Dali’s help for the elaborate dream sequences in the noir thriller Spellbound. Sadly, only two minutes out of twenty made it into the final cut of the film, and the rest of the footage has since been lost to time.

Hitchcock sought out Dali not for the press, but because according to him, no one could better represent the vividness of dreams. Prior to Dali, cinematic dream sequences were misty, vague affairs where themes and motifs were hinted at from behind a layer of plausible deniability.

Sequence designing for Hollywood is quite the step up from instigating arthouse riots in Paris, even if the final project failed to deliver the artist’s full vision. In 1976 Dali would write and direct Impressions of Upper Mongolia, a mockumentary about the search for an enormous psychedelic mushroom.

The climax of the film involves an elaborate flyover of an impossibly colored alien landscape which, upon a slow zoom out, is revealed to be a tarnished brass band on a pen Dali had spent a week peeing on. It is, likely through no small coincidence, the ideal film to watch while on mushrooms.

The Clock Melts Down

The end of Dali’s life was marked by a tragic fleecing. Of the millions he earned in his life, precious little remained of his estate near the end. He was investigated by the American IRS for tax absurdities. His hands started to shake so much he was often unable to perform the exacting strokes he based his work upon.

After Gala’s death, her body was smuggled back to Pubol wrapped in a blanket in the back of a car, and interred in the castle she spent so much of her life in. As his own health started to fail, some opportunists in Dali’s social circle seized the opportunity to pilfer whatever they could. Money went missing. A border in his childhood home walked off with briefcases full of personal papers and sketches, claiming they were to be documented and photographed in Paris. Of course, they were never to be seen again.

Delirious, Dali would sign whatever canvases and lithograph sheets were pressed in his hands, and the market was flooded with forged art. To this day, rumors of newly discovered Dali masterpieces are usually just convincing fakes drawn on a pre-signed sheet. Up to 50,000 such works may have been created, and the bulk still remain at large.

Instead of consigning the works to Spain through his foundation in the Dali Museum, as he declared earlier, Dali signed papers ceding copyright to a corporation owned by a long-time business partner.

Even in death, Dali’s life was marked by irony. His initial plan was to construct a tomb adjacent to Gala’s resting place with a hole between them, such that they could hold hands in the afterlife. Instead, the mayor of Figueres intervened just hours before Dali’s death and claimed that the artist had charged him with moving the final resting place to the Dali Theater and Museum, conveniently giving it a huge tourist attraction.