If you ask British schoolchildren, ‘what happened in the year 1066?’ they will undoubtedly answer ‘the Battle of Hastings’. Fought on October 14, it marked the successful invasion of England by the Duke of Normandy, William the Conqueror.

But earlier that year, another pivotal event took place.

Nine months earlier, on January 5, an elderly King died in the Abbey he had built, Westminster. His reign had been largely peaceful, stable, and prosperous, but he passed away without heirs, leaving the Kingdom in a chaotic mess with four different contenders laying claim to the throne.

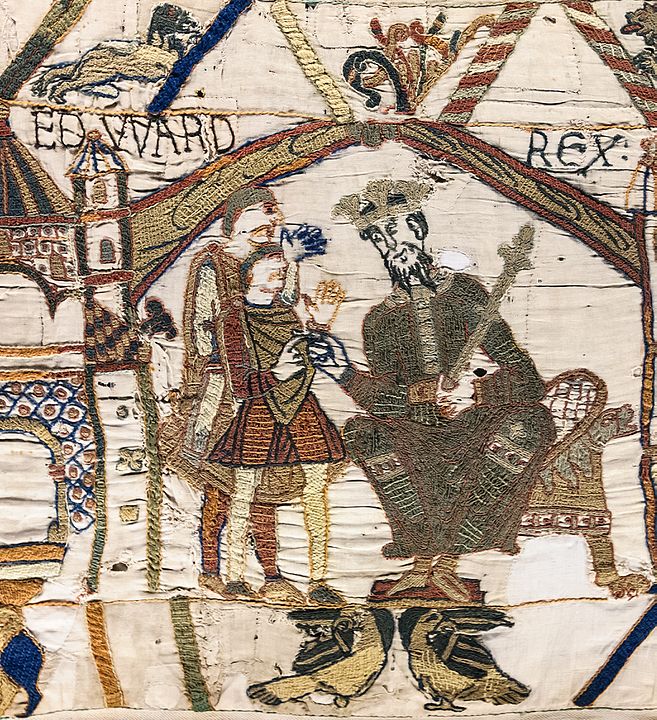

This is the story of that King, considered by supporters as a fair and pious monarch. He was slandered by his critics as weak and ineffectual, yet also prone to violence. He went down in history as both a King and a Saint — Edward the Confessor, the last Saxon King of England.

‘A Time of Evil’

If you know your history, you know that William the Conqueror defeated King Harold Godwinson at Hastings. So … Harold should be considered the last Saxon King, correct?

Well, yes and no.

As we’ll learn later, the legitimacy of Harold’s reign was contested from the start. And in any case, his tenure on the throne lasted only 10 months.

So, it may be more correct to say that Edward was the last real Saxon King of England, whose legitimacy was not disputed and who sat on the throne for a reasonable amount of time.

The claim of Edward as last Saxon King was upheld by none other than Winston Churchill. In his History of the English-Speaking people, Sir Winston thus describes the final moments of Edward:

“The lights of Saxon England were going out, and in the gathering darkness, a gentle, grey-beard prophet foretold the end. When on his deathbed, Edward spoke of a time of evil that was coming upon the land. His inspired mutterings struck terror into the hearers … Thus on January 5,1066, ended the line of the Saxon kings”

Churchill wrote this passage in April 1940, when Britain faced the serious threat of a German invasion. We can therefore understand if he foreshadows the Norman conquest as ‘a time of evil’.

We can also forgive that he overlooked an important fact about Edward: that he was half-Norman by birth, and culturally Norman by his upbringing. This is why we have placed a nice question mark in our title.

Last of the Saxon Kings – question mark.

A Kingdom Smote Asunder

Edward was born sometime between 1002 and 1005 at Islip, in Oxfordshire. His parents were Emma of Normandy and King Aethelred II of England, belonging to the noble house of Wessex. Aethelred was christened as ‘the Unready’, a styling that is more accurately interpreted as ‘the Unwise’ or the ‘one without counsel’.

As a King, Aethelred found it difficult to defend his lands from frequent raids by Danish Vikings. Aethelred tried to keep the Danes at bay by allying himself with the Normans. He cemented an alliance by virtue of his marriage to Emma, daughter of the Duke of Normandy.

This was Aetherlred’s second marriage. He had already fathered six children from a previous wife, of which the eldest, Edmund, was next in line to the throne. Emma gave two children to ‘the Unready’, Edward and Alfred.

An early biography of Edward claims that all English nobles already hailed him as their next king while still unborn. The same text mentions that, upon his birth, Edward was entrusted by his parents to the care of a monastic order.

This text may have been hagiographic, or intentionally aimed at celebrating Edward as a saint. Nonetheless, it sets the tone for two important forces that drove Edward’s future life: his desire to take the throne as a legitimate heir, and his deep religious beliefs.

During Edward’s early childhood, his father struggled to keep England free of Danish raids. He resorted to paying what we could define as ‘protection money’ to the Danes. This was ultimately money that Aethelred extracted from his subjects via a heavy tax known as ‘the Danegeld’.

The Vikings pocketed the money, of course. But according to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

“[they] went about as they pleased.” In other words, the bribe money hadn’t really altered their behavior all that much.

This was so true that, in 1013, Danish King Sweyn Forkbeard invaded England and laid siege to London. Aethelred initially mounted a successful resistance, but English nobles nevertheless took the occasion to oust him from power. They had been exasperated by his ineffective rule and by the burden of the Danegeld, so why not give the throne to that Danish fellow?

Aethelred, Emma, and their two children fled to safety in Normandy, where Edward was first exposed to Norman cultural influence.

Sweyn Forkbeard was crowned King of England on Christmas Day, 1013, but his reign was short-lived, as he died only five weeks later.

Aethelred the Unready returned on the throne, after he was recalled from Normandy by the Witan – the council of English noblemen. Aethelred sent ahead some ambassadors, led by his son Edward. He couldn’t have been more than 11 or 12, but he acted as a consummate diplomat, reassuring the nobles that his father would rule them fairly and protect them against further Danish offensives.

The Unready returned during Lent of 1014 and he immediately had to prepare to face Cnut, the son of Sweyn, who had very aggressive intentions. The new King of the Danes led raiding parties into much of Southern England throughout 1015 and 1016, plundering and slaying with gusto. His army had grown stronger, thanks to an alliance with Edric, the powerful Earl of Mercia, which is roughly equivalent to today’s Midlands.

All the while, Aethelred lay ill in the town of Corsham, and the marauding Vikings were opposed only by his son Edmund, nicknamed ‘The Ironside’.

On April 23, 1016, St George’s Day, Aethelred died. His people shed few tears, as the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle records that

“He ended his days … having held his kingdom in much tribulation and difficulty as long as his life continued.”

The Witan elected Edmund as King and the Ironside continued the fight. It appears that his half-brother Edward was by his side.

At this point, our protagonist must have been around 14 years of age, and he had displayed religious and diplomatic qualities so far.

That didn’t stop the young Prince from proving himself as one beast of a warrior. According to a Scandinavian source, during a battle with the Danes for the control of London, Edward came within striking distance of King Cnut. He then delivered a formidable downward blow with his sword. One of Cnut’s lieutenants, Thorkel the Tall, shoved his King out of harm’s way. But the force of the blow was such that it

‘smote asunder the saddle and the horse’s back’

So … mummy Emma may have raised him as a monk, but he turned out as an honorary Clegane.

After a defeat at Ashington, in the county of Essex, Edmund agreed to an alliance with Cnut. Under these terms, the Danes would retain control of Mercia and much of the north of England, while Edmund would rule over Wessex – which corresponds to South-Western England, from London to Cornwall.

In November of the same year, Edmund died of natural causes, and Cnut declared himself King of the whole of England, supported by a large part of the Witan.

Cnut-ling with the Enemy

To ensure the stability of his throne, Cnut set about to get rid of potential rivals.

First, he ordered the killing of Eadwig, younger brother of the late King Edmund.

Then, he exiled the two infant sons of Edmund to Sweden, arranging for them to be assassinated. Fortunately, this did not happen, but the two princes would not return to England for decades. The same fate could have befallen Edward and his brother Alfred, so they left the country for a second, voluntary exile in Normandy.

While there, Edward learned that in July 1017 his mother Emma had married Cnut.

That was a blow capable of breaking a horse in two!

Why had Emma of Normandy married a sworn enemy of their own family?

The marriage was, in fact, an astute political move, aimed at smoothing the transition from the old rule of the Wessex Saxons to the new reign. Emma was also aware that her own children were too removed from the line of succession, and that she risked deportation or even assassination if she did not accept the offer to marry Cnut. Lastly, Emma took the occasion to soften the otherwise harsh rule of Cnut, especially in the first years of his reign.

While Cnut travelled extensively back and forth between England and Denmark, Emma acted as de-facto ruler of the Country, reducing when possible the heavy taxes imposed by her husband. She also reimbursed Church property out of her own pocket after it was damaged by the rowdy Danish armies.

So, all in all, Emma’s second marriage was less an act of betrayal than a calculated move to protect herself and her adopted country. However, her distant teenage sons may have not understood this notion at the time.

Edward spent his formative years in Normandy, gradually turning to the Church and religion for comfort, support, and advice. In keeping with his ‘origin story’, the prince developed piety and devotion worthy of a Bishop, yet he maintained ambitions worthy of a King. He vowed he would return to England one day, as the rightful ruler.

But succession was not an easy affair.

First of all, Cnut already had a male heir earmarked to take his place — this was his son, Harold Harefoot, conceived from a previous marriage.

Edward’s ambitions were further frustrated when he learned that Emma and Cnut had sired another son, Harthacnut. As we say in England, they had an ‘heir and spare’, leaving very little chance for Edward to return to the throne.

The estranged siblings Edward and Alfred were forced to watch from afar as Emma groomed Prince Harthacnut for succession. No wonder, then, that Edward turned to his more distant Norman relatives for familiar comfort and support.

Over the years, Edward cemented his relationship with Norman aristocracy, bringing them to his cause. The Duke of Normandy himself, Robert I, attempted an invasion of England in 1034, with the goal of attempting to restore Edward to his rightful position. The expedition was thwarted by unfavourable winds, and the whole project was abandoned when Robert died the following year.

In November of 1035, another funeral took place, on the other side of the Channel: King Cnut had died. His son by Emma, Harthacnut, was declared King of Denmark, while Harold Harefoot stood in as regent for England.

Now, the de-facto King Harold had no reason to show any loyalty to Emma, his dad’s second wife. He could have gotten rid of her at any moment. Emma needed protection, and it may be for this reason that she invited her two sons back to England from Normandy.

Shortly after their arrival, Alfred was quickly captured by the opportunistic Godwin, Earl of Wessex, who wanted to ingratiate himself with the Harefoot.

Godwin slew most of Alfred’s party and then handed him over to Harold. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle describes what followed as such:

“A deed more dreary none in this our land was done,

since Englishmen gave place to hordes of Danish race.”

Harold’s men blinded poor Alfred with red hot pokers, and then left him to die inside a monastery.

Edward had to escape back to Normandy once again, adding Godwin to his list of enemies. Without support from her sons, Emma was eventually expelled by Harold and forced to live in Bruges, modern day Belgium. From there, she once again appealed to Edward, begging for his help in securing the succession in Harthacnut’s favour.

Understandably, Edward refused to provide any help. He was pious and religious and all that, but this was taking things a bit too far. In any case, Emma’s wishes came true even without help from Edward. When Harold Harefoot died in 1040, Harthacnut was able to take the throne in England.

The following year, Harthacnut proved to be a more magnanimous monarch than his father. He did not exile or assassinate potential threats to the throne. Actually, he did the opposite! Upon Emma’s insistence, he invited Edward back to England and designated him as his successor.

Suddenly, Edward was just a few months away from the goal of a lifetime.

In fact, on June 8, 1042 Harthacnut died in a way befitting of such turbulent times. He died by poisoning. Alcohol poisoning, to be exact.

In other words, he drank himself to death. Bless him.

King at last!

Even with Harthacnut’s blessing, Edward still needed the Witan, the council of nobles, to support his ascension. This was not a given, but he did enjoy their support thanks to the lobbying of the three most powerful Saxon Earls: Leofric, Siward and – wait for it – Godwin, Earl of Wessex.

Yes, the same guy who had played lackey to Harold Harefoot and who had caused the gruesome death of Edward’s brother, Alfred. It may sound strange, but Edward and Godwin did forge an uneasy alliance, borne out of political opportunism. Thanks to the Witan’s support, Edward was crowned King of England on April 3, 1043.

One of the first recorded actions taken by the new King took place on November 16, 1043. Edward, supported by Godwin and his retinue, paid a surprise visit to mother Emma, in Winchester.

In a swift action, Edward took revenge upon dear mum.

As I explained earlier, her actions after the death of Aethelred may have been politically justifiable. And she had insisted that Harthacnut invited Edward back to England. But on a personal level, it is understandable if Edward felt very little affection toward his mother.

The King seized all her lands, properties, and jewels. He even had her evicted from her official residence at Winchester castle. Emma died some nine years later, in virtual poverty and obscurity.

After this incident, Edward’s reign was fairly stable. As described by biographer William of Malmesbury

“There was no foreign war; all was calm and peaceable, both at home and abroad … he conducted himself so mildly that he would not even utter a word of reproach to the meannest person”

Malmesbury clearly appreciated Edward’s rule, as he praised his domestic policies:

“In the exaction of taxes he was sparing, as he abominated the insolence of collectors … This good king abrogated bad laws, with his witan established good ones, and filled with joy all that Britain over which … he ruled”

Nonetheless, Edward had to deal with internal conflict. The same Earls who had supported his claim, soon grew suspicious of Edward’s pro-Norman leanings. These were reflected in his administrative and ruling style. More visibly, the Norman influence was evident in the new abbey he ordered to be built: Westminster Abbey, the first English church in the Norman Romanesque architectural style.

Edward knew that of the Earls of the Witan, the most powerful was Godwin. He sought to prevent any conspiracy by becoming a relative of his: in January of 1045, Edward married Godwin’s daughter Edith.

Godwin may have twirled his moustache at the thought of becoming grandfather to a future King … except Edward, constantly torn between political power and religious pursuits, made a vow of chastity.

Edward’s demeanour was increasingly priestlike. He was popular among his subjects for his piety and devotion, soon developing a reputation as a holy man.

According to several biographers, God glorified King Edward with the gift of miracles. Chronicler Osbert of Clare tells a story of how the King helped a blind man from Lincoln to recover his sight, for example.

Or how about another anonymous biographer who wrote about a young woman who was plagued by a nasty infection of the throat and glands. The disease worsened so much that

“worms together with pus and blood came out of various holes”

One night, the woman dreamt that she would be healed if the King washed her face. Edward heard about her and agreed to carry out the treatment.

“Hardly had she been at court a week, when, all foulness washed away, the grace of God moulded her with beauty.”

This anonymous writer specifies that these prodigies left the English in awe, but also that Edward had been performing routinely similar miracles as a young man in Normandy.

Duel with Godwin

The Normans haven’t quite left the story just yet, which seems like a recurring theme for the life of Edward the Confessor. Edward’s mother was Norman, his upbringing was Norman, his most trusted advisors were Norman … and some time during his exile, he had even allegedly designated a Norman heir, Duke William.

In 1051, Edward appointed a Norman, Robert of Jumièges, as Archbishop of Canterbury, against the direct wishes of his father-in-law Godwin. Archbishop Robert was not too keen on Godwin, either, as he reported that the Earl was plotting to assassinate the King!

The relationship was reaching a breaking point.

Things went from bad to worse in September: the townsfolk of Dover attacked the retinue of a Norman visitor, the Count of Boulogne. In retaliation, the King ordered Godwin to exact punishment on the town.

Godwin refused. He began raising an army with his eldest sons Sweyn and Harold. The rebel Earl marched against the King, who was taken by surprise.

The English Crown could raise a national militia, but it needed time. Only the most powerful nobles could rely on standing armies, which they could mobilise in a short time.

In this case, Edward was saved at the last moment by the Earls Siward and Leofric, who led a powerful contingent against Godwin. The kingdom was spared a civil war, though, as both parties weren’t really keen to fight. And who could blame them?

Edward and Godwin agreed on a different way to settle their dispute. They would convene a meeting of the Witan in London by the end of 1051, at which the Earl of Wessex and his sons would vent their grievances against the King.

Edward got wind that Godwin, Sweyn, and Harold were coming to London. Alright, but they were bringing along their army. The King now had more time to act, and so he issued an order for the militia to be convened from all English lands.

Most of the knights in Godwin’s service were more loyal to the King than to their Earl, and so they abandoned the Wessex forces to join Edward. By the time Godwin arrived to London, his forces had melted away.

King Edward delivered the next blow by outlawing the Earl and his family. In a matter of days, they had all left England. Harold and another brother had sought refuge in Ireland. Godwin and his other sons exiled themselves to Flanders.

Next, Edward confiscated all of Godwin’s estates and riches before enacting the final stage of his revenge play. You may remember that Godwin was actually the King’s father-in-law. Well, Edward decided he couldn’t trust his own wife, Edith, so he sent her away to a nunnery.

Edward’s advantage against Godwin’s family was short-lived, though. Without the meddlesome father-in-law around, Edward took the occasion to invite more Norman advisers at court. This ill-advised decision irked some members of the Witan, who turned their sympathies toward the exiled Earl of Wessex.

In the summer of 1052, Godwin returned to England, landing in Kent with a powerful fleet. At the same time, his son Harold – a competent military leader – disembarked in Devon. The two armies converged near Sandwich and from there launched an attack towards London.

The Anglo-Saxon chronicle describes how, on this occasion, Edward’s reaction was slow and indecisive. Many southern lords and knights had already sided with Godwin, due to their anti-Norman sympathies.

As Godwin’s army swelled and marched to London, it plundered, burned, and looted without restraint. Many landowners went to King Edward to ask for help, but when he failed to mount a timely counterattack, they were all too happy to switch sides.

When Godwin and Harold reached London, Edward’s army and fleet were entirely surrounded by their enemies. Once again, England was on the brink of a large-scale civil war, and once again, it was averted at the last minute when officers from both armies preferred to parley rather than fight.

The truce was followed by another meeting of the Witan in London, which resulted in a humiliating defeat for Edward.

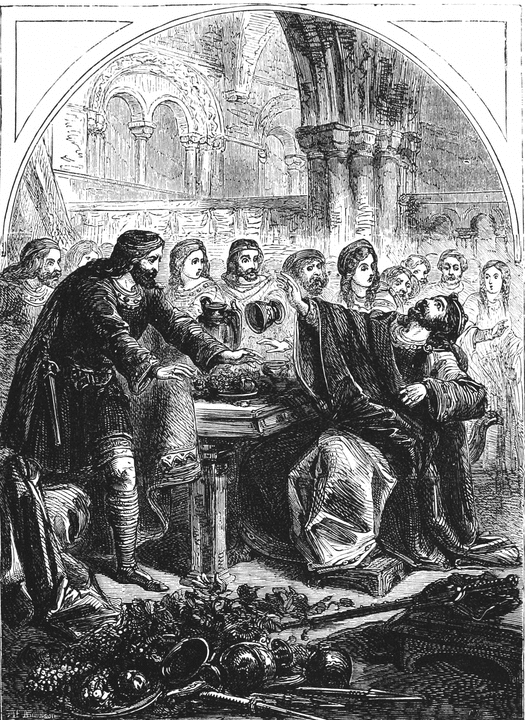

At the council, Godwin and his sons were cleared of all charges that had been laid against them: treason, rebellion, conspiracy to assassinate the King, and even Godwin’s role in causing the death of Alfred. Edward, pressed by the majority of the nobles, had to comply.

The Witan also demanded for Archbishop Robert to be proclaimed an outlaw, alongside other Norman advisors.

Godwin died the following year in quite a dramatic fashion. Evidently, he choked on a piece of bread after swearing to the King:

“Let God Who knows all things be my judge! May this crust of bread which I hold in my hand pass through my throat and leave me unharmed to show that I was innocent of your brother’s death!”

Despite the schottenfreude of his death, Godwin and family had emerged victorious from their duel with Edward. Moreover, the Norman influence had been removed from court. If Duke William of Normandy wanted to sit on the English throne, he would have to earn that right by force.

Securing the Succession

As King Edward entered his sixth decade, it became clear that he would die childless. Who would succeed him?

We already know that he would have appointed William of Normandy as his heir on a previous occasion, but this choice was not palatable to the Witan. The council of nobles pressed for another alternative. Do you remember the children of Edmund ‘Ironsides’, exiled to Sweden?

Well, the eldest, who was also called Edward, was still alive and kicking in Hungary. In 1056, the King decided to have him brought back to England. He entrusted this difficult task to his old enemy: Harold, son of Godwin, now Earl Harold Godwinson.

After the death of Godwin, Edward had learned to appreciate Harold’s qualities. Unlike his father, Harold had proven to be loyal to the King, and he was also a successful military leader. He had proven his skill by leading several victorious campaigns against a rebellious Welsh leader, Prince Gruggydd.

Harold succeeded in his mission, returning with Prince Edward in summer of 1057. But on August 31, the Prince died of unknown causes.

Had he been poisoned by Harold?

According to pro-Norman sources, yes. More realistically, no. If that was Harold’s intention, why not kill the Prince during the long journey back from Hungary?

Prince Edward died leaving a young son behind, Edgar ‘Aetheling’ – or ‘throne-worthy’. He was considered by part of the Witan as another possible candidate to the throne, despite his young age. A larger faction, in the meanwhile, started to consider Harold as a more palatable successor.

He was an effective military leader, brother-in-law to the king and ruler of the most powerful of English earldoms.

Harold’s star continued to rise in the early 1060s.

Edward gradually withdrew from government matters, preferring to dedicate his time to prayer, religious studies, and the completion of Westminster Abbey. The King preferred to delegate most serious matters to Harold and other members of his family.

In 1063, Harold’s younger brother Tostig quelled a rebellion in Northumbria, following which the two brothers crushed once and for all Prince Gruggydd in North Wales. Ever more dependent on Harold, in 1064, Edward sent him on a diplomatic mission to Normandy, during which he met with Duke William.

What happened at the meeting, is disputed. According to pro-Norman sources, the aim of Harold’s mission was to confirm to William that he was the designated successor to the English throne; according to pro-Saxon accounts, Harold was to negotiate an alliance with the Normans, and the succession was not even discussed.

The already puzzling situation was made even more confusing by King Edward himself. At the end of 1065, the King fell ill, and there was nothing that could be done. As he lay on his deathbed, during the first calendar week of the new year, he called for Harold and pledged the crown to him, as a reward for his services.

Or at least, that’s Harold’s version. King Harold Godwinson rushed to have himself declared King the very same day of Edward’s death — January 5, 1066.

Saint Edward

King Harold’s position was all but secure. Edgar the Aetheling may have not been a credible contender, but William of Normandy was a fearsome rival. If that wasn’t enough, there was a fourth claimant to the throne, Norwegian King Harald Hardrada.

I will not go into the details of what happened next. For those, you can search for our Biographics video on William the Conqueror.

I will consider King Edward’s legacy, instead.

His record as a successful leader is criticised by some historians. His reign was largely peaceful, sure, but he could have spared the country much in-fighting had he acted more decisively when dealing with Godwin.

His predilection for Norman customs and his own Norman heritage was perceived positively by pro-Norman chronicles. In fact, he could be considered the first of the Norman Kings, rather than the last of the Saxons!

However, his unchecked bias toward advisors and bishops from that land eventually caused discontent amongst Saxon noblemen.

Over time, memories of his piety and stories of his miracles took over his more earthly deeds. In 1163, almost a century after his death, Edward was formally proclaimed a Saint, and styled ‘The Confessor’. This title indicates a saint who suffers for his faith, but is one step short of martyrdom.

In 1269, Edward’s bones were laid in Westminster Abbey — his Abbey, which back then was the most sumptuous shrine in the western world. Edward was England’s patron saint until 1348, when he was replaced by Saint George. His cult remained alive for centuries, though, and sick pilgrims would sleep by his shrine in the hope of being cured.

LINKS AND SOURCES

General biographies on St Edward

https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofEngland/Edward-The-Confessor/

https://www.scribd.com/book/193657693

https://www.scribd.com/book/273561636

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

https://www.scribd.com/book/444691438

Map of Saxon England

https://www.historic-uk.com/assets/Images/mapofanglosaxonengland.jpg?1390903168

Aethelred the Unready

https://www.royal.uk/ethelred-ii-unready-r-978-1013-and-1014-1016

Emma of Normandy

https://www.historic-uk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofEngland/Emma-Of-Normandy/

Godwin of Wessex

https://www.historytoday.com/archive/rebellion-earl-godwin

Robert I of Normandy

http://www.englishmonarchs.co.uk/normans_20.html

Edward’s succession

https://www.academia.edu/30031791/Edward_the_Confessor_and_the_Succession_Question

https://www.academia.edu/23861154/Edward_the_Confessor_revision