He was one of the world’s most notorious and ruthless leaders. Since coming to power in 1979, Saddam used any means necessary to hold onto Iraq including killing anyone who stood in his way. At a young age he was brutalized at home, ran away to his uncles, and quickly became a thug for an extremist political party. As he raised through the ranks and took over, he modernized the country — and ruled through fear. Eventually his greed, defiance, and murderous ways led to the gallows.

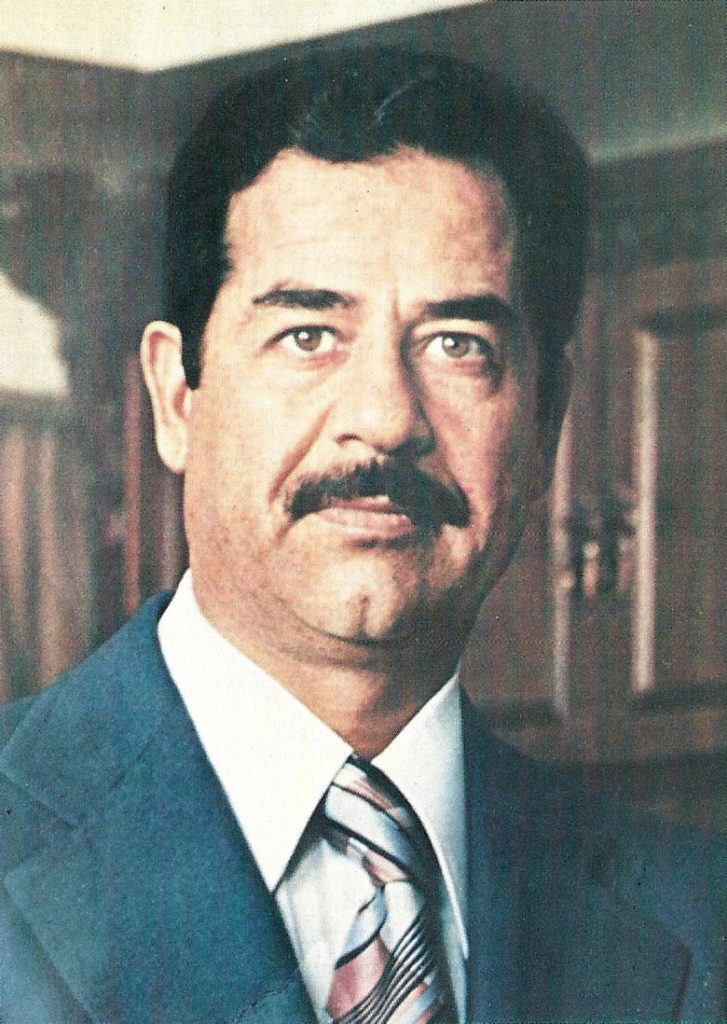

Today, on Biographics we learn about the life of Iraq’s former president Saddam Hussein.

Early Life

On April 28, 1937, Saddam Hussein was born to a peasant woman in a mud and straw village called Al-Awja near Tikrit, on the banks of the Tigris River. Saddam bore the physical mark of his tribe on the wrist of his right hand; a tattoo of three dark blue dots. Most people in his village lived in severe poverty and life was difficult. Saddam’s father, a sheepherder, disappeared before he was born. Then, a few months later, Saddam’s 12-year-old brother died from cancer. This sent Saddam’s mother Subha into a crippling depression and she attempted to abort her unborn baby and kill herself. She failed and when her infant son was born she named him Saddam, which means in Arabic the “one who confronts,” or “the stubborn one.”

Without a husband, Subha didn’t have the means to support her baby. She sent Saddam to live with her brother Khairallah Talfah, a retired army officer and Arab nationalist in Tikrit. Saddam lived with him for only three years, until Talfah was imprisoned due to his part in a coup to overthrow the pro-British government in Iraq. By this time, Saddam’s mother had remarried a man named Ibrahim Hassan. Villagers knew him as “Hassan the liar.”

Back at his mother’s home, the young Saddam endured regular beatings and maltreatment at the hands of his stepfather. Neighbors and early friends of Saddam recall Hassan beating him to wake in the morning and regularly shouting things like, “You son of a dog, I don’t want you!” He was forbidden from going to school, and instead was made to be useful by stealing goats and chickens for the family. If Saddam was caught stealing — it has been said — he would rather poison the animals than return them to their owners.

At the age of 10, Saddam heard his uncle had been released from prison and he fled to Tikrit to be with him. Talfah filled the boy with dreams of glory, saying he would be a great leader of Iraq someday. He gave Saddam his first real possession — a handgun. Saddam reportedly used the weapon to threaten his primary school teachers and he may have murdered a man when he was not yet a teenager. According to the story, after the killing police showed up at Talfah’s house and found Saddam sleeping with the gun, still warm, under his pillow.

Under his uncle’s care, Saddam was finally able to go to school but he learned much more than how to read and write. Through the years he was deeply influenced by Talfa’s politics and after leaving the al-Karh Secondary School in 1957, at the age of 20, Saddam joined the Arab Ba’ath Socialist Party as a low-level thug and gunman. The party was formed in Syria in 1947 with the ultimate goal of unifying the various Arab states in the Middle East. At the time, it was the most radical, nationalist party in Iraq and it had become an underground revolutionary force.

When he was 22, Saddam played a major role in the Ba’ath Party’s assassination attempt of the then-Iraqi Prime Minister Abdul Karim Qassim. During the attack on October 7, 1959, Saddam and other assassins ambushed Qassim’s car on Baghdad’s busiest street. The Prime Minister’s chauffeur was killed but Qassim was spared, surviving gunshot wounds in the arm and shoulder. Saddam escaped with a bullet in his leg. The official version of the story portrays Saddam as a hero who dug the bullet out with a penknife. Another version suggests that the plot failed because Saddam opened fire prematurely. Several of the would-be assassins were caught, tried and executed but not Saddam. He managed to flee to Syria before eventually seeking refuge in Egypt. While in Egypt, Saddam studied law at the University of Cairo.

Saddam returned to Iraq in 1963 after a successful military overthrow of Qassim’s government. After his return, Saddam was recruited for yet another assassination. The Ba’ath Party suffered from infighting and a coup was planned to overthrow the leader. The plan was ultimately betrayed however and Saddam became a wanted man. He was forced into hiding but was caught and imprisoned in 1964. While in captivity, he remained active in party politics and read up on his role models — tyrants Joseph Stalin and Adolf Hitler. In 1966, Saddam escaped prison thanks to the help of sympathetic prison guards. Afterwards, he was appointed deputy secretary of the Regional Command, and became a rising star in the Ba a’th organization.

Rise to Power

In 1968, another successful coup in Iraq put Saddam’s Ba’ath party in power and President Ahmed Hassan al-Bakr (Saddam’s cousin) named him deputy and head of the secret police. Saddam proved to be a ruthless, but effective politician. Within government, he either eliminated or co-opted individuals who stood in his way. Eventually, he clawed his way to become the vice president of Iraq’s Revolutionary Command Council (RCC), the core group that held Iraq’s Ba’athist government together. Although not the official president of Iraq until 1979, Saddam truly held the reins from the early 1970s onward.

When the Ba’ath Party seized control, it did not enjoy widespread support across the country. That changed after Saddam nationalized Iraq’s oil industry in the early 1970s before the energy crisis of 1973. As a result, the nation enjoyed a boom to the economy and the massive earnings allowed the Ba’athist government to fund the health, education, and public works sectors and expand social programs. In an attempt to wipe out illiteracy, Saddam required all children to attend school and made it free through high school. He also provided free hospitalization to all Iraqis and full economic support to the families of Iraqis soldiers. Such reforms were unheard of in any other Middle Eastern country. In the years before the Iran-Iraq War construction became one of the prized occupations of Iraq’s middle class. It is also important to note, 40 percent of the increased revenue from oil went to buying armaments from Western and Soviet suppliers. That figure increased at the onset of the war with Iran.

In 1979, when al-Bakr attempted to unite Iraq and Syria, in a move that would have left Saddam effectively powerless, Saddam forced al-Bakr to resign, and on July 16, 1979, Saddam Hussein became president of Iraq. Five days later, he called an assembly of the Ba’ath Party — consisting of roughly 250 people. At the meeting, party officials sat mystified as Saddam made the announcement he had uncovered a plot against him — and he claimed the conspirators were in the room. An alleged informant then read a list of 68 names out loud, and each person was promptly arrested and removed. All the individuals were eventually tried and found guilty of treason. Twenty-two were sentenced to death. The whole ordeal was filmed and circulated around Iraq. This was an intentional, well-scripted display of Saddam’s power and a clear message of who was in charge.

Three months later, Saddam declared 14 people (up to 13 of them Jews), part of a “Zionist spy ring.” He made a very public, carnival-like display out of their execution by stringing them up before a crowd of thousands in downtown Baghdad. Over the next several months, Saddam had more “plotters” murdered live on television and he hung them up on city lampposts.

To guard against coups and ensure loyalty, Saddam surrounded himself with kin — putting his fellow clansmen in government positions. He regularly used informants and the secret police to route out suspected conspirators. If anyone so much as made a joke about Saddam, they could have their tongue cut out or pay with their life. He believed it was better to murder a person of suspicion and be wrong — than it is was to not, and be killed by them.

Personal Life

Saddam married his first cousin, Sajida — his uncle Talfah’s daughter. They had five children including two sons, Uday and Qusay, and three daughters, Raghad, Rana and Hala. He took on mistresses but did not parade them around publically. Later on, when his sons grew up, he gave them high-ranking positions within Iraq’s government.

Saddam’s public image was meticulously crafted — he dyed his hair black, sported a mustache, and refused to wear his reading glasses unless in private. He had a slight limp due to a slipped disc so he was never filmed walking for more than a few steps. He was 6’ tall, and his weight fluctuated from trim to chubby but his well-tailored suits were made to disguise his protruding belly.

Each of his 20 palaces was kept fully staffed, with meals prepared daily as if he were in residence to disguise his whereabouts. He moved around frequently and used body doubles to thwart assassination attempts. His meals, such delicacies like imported lobster, were first tested for radiation and poison. His wine of choice was Portuguese, Mateus Rose, but he never drank in public to maintain the conceit that he was a strict Muslim.

Saddam was particularly phobic about germs and even top generals summoned to meet him were often ordered to strip to their underwear and their clothes were then washed, ironed and X-rayed before they could get dressed to meet him. They had to wash their hands in disinfectant. During his imprisonment, it is said he would try to maintain this cleanliness by wiping his utensils and food tray with baby wipes before eating.

Throughout his rule, he maintained a limited world-view and possessed little knowledge of Western culture, laws, and advancements in technology. He was once shocked to learn there was no such law in the U.S. that prevented citizens from complaining about the President.

Decades of Conflict

The same year that Saddam anointed himself president of Iraq, Iran’s Ayatollah Khomeini led a successful Islamic revolution. Saddam’s political power rested in part upon the support of Iraq’s minority Sunni population and he worried that developments in Shi-ite majority Iran could lead to a similar uprising in Iraq. In response, on September 22, 1980, Saddam ordered Iraqi forces to invade the oil-rich region of Khuzestan in Iran — a clear violation of international law. The conflict soon turned into an all-out war; one Saddam foolishly expected would be over in a matter of weeks. Saddam had no prior military experience and he grossly underestimated his enemy. Iran was three times the size of Iraq and a formidable opponent. A stalemate ensued, with both sides engaged in a bloody trench war.

At the same time ground troops were deadlocked, Saddam sunk millions of dollars into developing nuclear weapons. In 1981, Israel took this matter seriously — believing if Saddam had the ability, there would be no preventing him from dropping an atomic bomb on their cities. In June, the Israeli Air Force destroyed Iraq’s research center at Osirik. At least 25 pounds of enriched uranium were reported to have been on the site. The plant was near completion and scheduled to begin operations within a matter of months.

The destruction of Iraq’s nuclear plant was humiliating and with no end in sight to the war, Saddam consulted his cabinet. At the meeting, Saddam’s health minister suggested that he step down in order to gain the ceasefire with Iran. As the story goes, Saddam thanked him for his candor and had him arrested on the spot. The minister’s wife pleaded with Saddam to release her husband and he promised he would. When he sent him home the next day, he was delivered in a black canvas body bag, cut up into tiny pieces.

In the closing days of the war with Iran, Saddam’s murderous ways reached new heights. In his most savage act, he poisoned thousands of civilian Kurds using chemical gases, killing upwards of 5,000 people and injuring 10,000 more. The genocide became known as the Halabja Massacre or Bloody Friday. Iranian photographer Kaveh Golestan witnessed the gas attacks from a helicopter.

“It was life frozen. Life had stopped, like watching a film and suddenly it hangs on one frame. It was a new kind of death to me. (…) The aftermath was worse. Victims were still being brought in. Some villagers came to our chopper. They had 15 or 16 beautiful children, begging us to take them to hospital. So all the press sat there and we were each handed a child to carry. As we took off, fluid came out of my little girl’s mouth and she died in my arms.”

One decade after the attack, at least 700 people were still being treated for severe after effects of the Halabja Massacre. Surveys have concluded the Kurdish population in this region suffer from a higher percentage of medical disorders, birth defects, and various diseases including cancers and heart disease.

On August 20, 1988, after years of intense conflict that left one half million casualties on each side, a ceasefire agreement was finally reached. The eight year war ravaged Iraq’s economy and infrastructure. One million Iraqi soldiers were out of work.

At the end of the 1980s, Saddam turned his attention toward Iraq’s wealthy neighbor, Kuwait. Saddam believed the Kuwaitis had 200 billion dollars in various banks around the world. And, a takeover of this small country would yield him all the riches he needed to pay back Iraq’s war debt and stabilize his country. Using the justification that Kuwait was historically part of Iraq, Saddam ordered the invasion on August 2, 1990. It took only six hours for Saddam’s armies to the occupy the country — a move greatly condemned around the world. A UN Security Council resolution was promptly passed, imposing sanctions and setting a deadline of January 15, 1991, for the Iraqis to leave Kuwait. During the occupation, Saddam staged a number of bizarre televised interviews with citizens of Kuwait in which he asked them if they were happy with the Iraqis invasion. Of course, they said yes…they didn’t have a choice!

When Saddam ignored the January 15 deadline, a coalition force headed by U.S. President George H.W. Bush confronted Iraqi forces. Saddam was no match for America’s firepower and modern warfare technology. Within six weeks Saddam’s troops were out of Kuwait. A ceasefire agreement was signed, the terms of which included Iraq dismantling its germ and chemical weapons programs. The previously imposed economic sanctions levied against Iraq remained in place. Despite this and the fact that his military had suffered a crushing defeat (an estimated 150,000 Iraqis died), Saddam claimed victory in the conflict. He called “The Mother of All Battles” his biggest victory and maintained that Iraq had actually repulsed an attack by “America and its criminal gang.” He said, “Iraq has punched a hole in the myth of American superiority and rubbed the nose of the United States in the dust.”

During the 1990s, various Shi-ite and Kurdish uprisings in Iraq occurred, but the rest of the world, fearing another war, did little or nothing to support these rebellions and they were ultimately crushed by Saddam’s forces. At the same time, Iraq remained under intense international scrutiny. Saddam violated the terms of the UN’s peace deal — when inspectors were sent into Iraq they found and destroyed stockpiles of weapons including chemical and biological warheads and a “super gun” with missiles capable of reaching Israel. The inspectors also alleged Saddam was still at work developing nuclear weapons. In 1993, when Iraqi forces violated a no-fly zone imposed by the UN, the U.S. launched a damaging missile attack on Baghdad. Further strikes occurred in 1998.

With economic sanctions still in place in the years following the Gulf War, Saddam continued to maintain his personal wealth, and his family’s, through selling oil and medical supplies meant for his people on the black market. While the citizens of Iraq were in dire straits, he built opulent palaces and maintained his lifestyle.

Saddam’s Fall

After the terrorist attacks on the U.S. in September 11, 2001, President George W. Bush and members of his administration suspected Saddam’s government of having a relationship with Osama bin Laden’s al Qaeda organization. And, of possessing “weapons of mass destruction.” In his January 2002 State of the Union address, President Bush named Iraq part of his so-called “Axis of Evil,” along with Iran and North Korea. Later that year, UN inspections of suspected weapons sites began, but little or no evidence that such programs existed was ultimately found. Despite this, on March 20, 2003, under the pretense that Iraq did in fact have a covert weapons program and that it was planning attacks, a U.S.-led coalition invaded Iraq. Within weeks, the government and military had been toppled, and on April 9, 2003, Baghdad fell. Saddam, however, managed to elude capture.

In the months that followed, an intensive search for Saddam began. While in hiding, Saddam released several audio recordings, in which he denounced Iraq’s invaders and called for resistance. Finally, on December 13, 2003, Saddam was found hiding in a hole in the ground, a bunker near a farmhouse in ad-Dawr, near Tikrit. The once well-dressed and groomed leader looked disheveled, unshaven and bewildered when he was arrested.

Saddam was moved to a U.S. base in Baghdad, where he would remain until June 30, 2004, when he was officially handed over to the interim Iraqi government to stand trial for crimes against humanity. With his days numbered, Saddam showed no accountability or remorse for his crimes. In 2003, when asked by Iraqi politicians about his brutal acts, Saddam called the Halabja attack Iran’s handiwork; said that Kuwait was rightfully part of Iraq and that the mass graves were filled with thieves who fled the battlefields. Saddam declared that he had been “just but firm” because Iraqis needed a tough ruler.

During his trial, Saddam would prove to be a belligerent defendant, often boisterously challenging the court’s authority and making bizarre statements. On November 5, 2006, Saddam was found guilty and sentenced to death. The sentencing was appealed, but was ultimately upheld by a court of appeals. On December 30, 2006, at Camp Justice, an Iraqi base in Baghdad, Saddam was executed. He was then buried in Al-Awja, his birthplace, on December 31, 2006. This closed the chapter on one of modern history’s most tyrannical and brutal dictators.