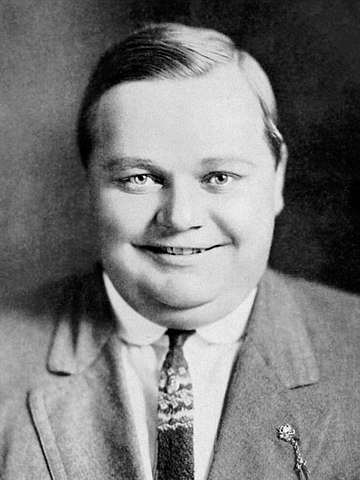

September 5, 1921. It was Labor Day and Roscoe Arbuckle was hosting a party in a suite of the St. Francis Hotel in San Francisco. He had every reason to be happy. “Fatty” Arbuckle, as he was known, had been one of the most successful movie stars of the 1910s and, given that he had just signed another big, lucrative contract with Paramount Studios, all signs pointed to the 1920s being just as profitable for the portly performer.

But then one party changed everything. One woman mysteriously fell ill and died. Another one laid the blame on the actor and, just like that, Arbuckle found himself charged with causing her death.

For the tabloids, this was journalistic dynamite as they squeezed every little juicy detail onto their front pages, with little regard for the truth. Meanwhile, Hollywood was concerned with its own survival and completely distanced itself from the once-popular actor.

This left Fatty Arbuckle fending for himself, as he became the target of the biggest scandal in America.

Early Years

Roscoe Conkling Arbuckle was born on March 24, 1887, in the small town of Smith Center, Kansas, one of nine children to William Goodrich Arbuckle and Mary Gordon. The family moved to Santa Ana, California, when he was an infant. Right off the bat, Roscoe was a larger-than-life individual. His reported birth weight ranged from a sizable 14 pounds to a gargantuan 16 pounds. Either way, he was a big boy and his birth may have caused health problems for his mother which persisted until her death.

His father resented him because of this, but also because he suspected that Roscoe might have been an illegitimate child since both William and Mary were small, slim people. In fact, you can tell the contempt that William Arbuckle had for his child from his name alone. He named his son Roscoe Conkling after a prominent Republican senator, even though William Arbuckle was a Democrat and despised him.

As you might imagine, childhood was not a happy time for Roscoe (the future actor, we mean, not the politician). At home, he was shunned and abused by his father. At school, he was bullied and mocked by the other kids due to his weight. Already, he became known as “Fatty,” a nickname that followed him for the rest of his life. Roscoe became a shy introvert who often turned to food for comfort which, of course, trapped him in a vicious cycle – the taunts and jeers of his schoolmates led to overeating, which made Roscoe even bigger and led to more mockery.

Fortunately for him, the young boy soon discovered his calling – the stage. Whenever he found himself in front of the spotlight, that shy, self-conscious boy turned into a dedicated performer. Arbuckle made his theater debut when he was only 8 years old and, from then on, he knew that showbiz was the life for him. It didn’t matter if it involved singing, dancing, clowning, or acrobatics – Roscoe was surprisingly good at all of them.

Roscoe’s mother died in 1898 when he was 12 years old, and his father wanted to have nothing more to do with him. Out on the streets, the teenager traveled to San Jose, where he found a job working in a hotel. Thanks to his habit of singing while working, a professional singer overheard Roscoe one day and suggested that he try out on amateur night at a local theater. This was back when stage managers used giant hooks to pull bad acts off the stage, the kind that you & I have only ever seen in old Looney Tunes cartoons. Arbuckle greatly feared the humiliation of “getting the hook,” but it worked out well for him that night. During his turn, nerves got the best of him and Arbuckle left the audience less-than-impressed with the songs he performed. The dreaded hook emerged from the left of the stage, but Arbuckle tried to evade it by jumping out of the way. He ended up doing a somersault and landing in the orchestra pit, to the raucous laughter of the audience. He won the contest and earned himself some appearances at a few other theaters. The following year, Arbuckle became part of the Pantages Theater and, in 1906, he toured the country with a vaudeville show as one of their main attractions.

The Big Screen

In 1908, Arbuckle met and married his first wife, a singer named Minta Durfee. By that point, he had earned some renown in the theater world, so a move to the silver screen was only a matter of time.

Fatty Arbuckle made his movie debut in 1909, appearing in a short titled Ben’s Kid. In the following years, he made a few more shorts with the same studio, the Selig Polyscope Company, before he moved to Keystone Studios where his career kicked off in earnest.

The man who founded Keystone Studios, Mack Sennett, was known as the “King of Comedy,” and he built his reputation around a series of popular shorts featuring the side-splitting and incompetent antics of the Keystone Cops. These movies proved to be the perfect vehicle for Arbuckle to display his talent at slapstick humor and he starred in dozens of these shorts, oftentimes alongside silent-era actress Mabel Normand, who also gained fame due to her comedic chops. In one of their first projects together, 1913’s A Noise from the Deep, the duo might have made movie history when Arbuckle became the first person to get pied in the face on camera, courtesy of Normand.

By 1914, “Fatty Arbuckle” was comedy royalty and he even started directing some of his shorts. He also gave some up-and-coming actors their big breaks, including his own nephew, Al St. John, and the future comedy legend Buster Keaton. His personal life wasn’t doing so hot, though. His relationship with his wife had become strained due to Arbuckle’s heavy drinking, a habit he had picked up during his days touring with vaudeville shows. And in 1916, he had a serious health scare when he developed an infection on his leg that could have required amputation. Ultimately, Arbuckle’s leg was saved, but the actor went on a crash course to lose some weight as fast as possible, which caused a brief morphine addiction.

The setbacks in his personal life did nothing to dim Arbuckle’s ever-growing stardom, however. In 1917, he founded his own film company named Comique to have more creative control over his shorts. However, just a year later, he relinquished control over to Buster Keaton when Paramount Studios made him an offer he couldn’t refuse: an unparalleled three-year contract of $1 million per year.

The Party

Arbuckle may have been making big bucks, but his fat contract also came with an increased workload as he almost always worked on multiple movies at once. Roscoe was getting a little burnt out, so when the opportunity came for a little R&R, he jumped at the opportunity.

It was Labor Day, 1921, and Arbuckle had planned a three-day trip to San Francisco alongside friend and director Fred Fischbach. Right off the bat, the trip had an inauspicious start. Fatty thought about canceling the whole trip after suffering an injury to his prodigious posterior. There are several tales of how this came about, but the most popular one claims that Arbuckle had brought his luxurious Pierce-Arrow automobile to a garage to be serviced and, while waiting, he accidentally sat down on an acid-soaked rag and suffered second-degree burns to his buns. Anyway, Fischbach eventually persuaded Arbuckle not to let a little mishap get in the way of their fun so the two of them, plus actor Lowell Sherman, jumped in Roscoe’s Pierce-Arrow and headed to San Francisco, where they had booked three lavish rooms at the St. Francis Hotel.

Even though Prohibition had been in effect for over a year and a half by that point, booze was still not hard to find, especially when you were one of the biggest movie stars in the world. Once arrived at the hotel, Arbuckle & Company received a shipment of whisky and gin in anticipation of the party they were planning to throw.

On September 5, 1921, their little shindig was in full swing. Room 1220 had been designated as the “party room” while adjoining rooms 1219 and 1221 were the sleeping quarters for Arbuckle and his two companions. Among the various attendees of the festivity was a 26-year-old small-time actress named Virginia Rappe, who came accompanied by her publicist, Alfred Semnacher, and another woman called Maude Delmont. Whether or not they were invited is uncertain, but with the booze flowing and the music playing, they soon made themselves at home.

At one point, Rappe needed to use the bathroom, so she went into room 1219, which belonged to Arbuckle, and was soon followed by the actor himself. The two of them were alone in the room for an undetermined length of time – some people said ten minutes, others said an hour. Eventually, though, other partygoers made their way inside and found Virginia Rappe on the bed, barely conscious and looking deathly ill. The young woman was writhing in agony, complaining of a sharp, piercing pain in her abdomen. The hotel doctor was summoned but, unbeknownst to everyone, he had clearly just entered a “Worst Doctor in the World” Competition, because he concluded that Rappe had simply had too much to drink and burst out in hysterics. He gave her some morphine to shut her up and moved her to another room to “sleep it off.”

The following day, Arbuckle checked out of the hotel and left San Francisco. For reasons we still cannot comprehend, even though Rappe was still ill, she was not taken to the hospital, but rather she was kept in the hotel for a few more days, on a steady diet of morphine. When her condition kept getting worse, she was finally checked into a hospital, but by then it was too late. On September 9, Virginia Rappe died of peritonitis, an acute infection that was caused by a ruptured bladder. But then a new question arose – what exactly caused her bladder to rupture?

The Crime

Right off the bat, Arbuckle was suspected to have been involved in the young actress’s death. Mainly, this was due to Rappe’s companion, Maude Delmont, who kept telling everyone who would listen that the rotund actor had sexually assaulted Rappe and then caused her bladder to rupture under the weight of his enormous girth. Later, we’ll go over the fact that Maude Delmont had numerous charges of fraud, extortion, and blackmail on her record and that she was almost allergic to the truth but, for now, it seems that her statement was enough to convince the authorities. Just two days after Rappe’s death, San Francisco police arrested Roscoe Arbuckle.

His story was as follows: at around 3 pm the day of the party, Arbuckle agreed to drive a friend of his into town. He went into his room to get changed and found Virginia Rappe on the floor of his bathroom. He picked her up and placed her on the bed and brought her a glass of water. Since Arbuckle thought that the young woman was simply drunk, he went about his business, but Rappe soon rolled out of bed onto the floor and began moaning and writhing. The actor put her to bed again and brought her a bucket of ice. Her cries of anguish attracted other partygoers into the room, who saw Arbuckle holding an ice cube on her stomach in an attempt to dull her pain.

Like Arbuckle, their instinct was to assume that Rappe was drunk, but then the actress allegedly screamed the words that doomed his career: “He did this to me.” And we stress the word “allegedly.” In the days that followed, Delmont brought in a doctor friend of hers to look in on Rappe and specifically told him to check for any signs of sexual assault, but he didn’t find any. Despite this, Delmont stuck to her story, and police charged Arbuckle with first-degree murder.

The actor had two important enemies working against him. One was San Francisco District Attorney Matthew Brady, who immediately understood that this could be a career-making case for him and was determined to obtain a guilty verdict, truth be damned. The other one was William Randolph Hearst, the newspaper magnate and yellow journalism pioneer who realized that his tabloids could leech off this scandal for months. No detail was too debauched or too gruesome and the truth, once again, was simply a third wheel that would not get in the way of a juicy story. It was in Hearst’s newspapers that the most sensational parts of the affair took life, such as the rumor that Rappe’s bladder had ruptured because she had been violated with a champagne or Coke bottle. Even today, this is sometimes mentioned, despite the fact that this was never alleged during the trials.

For Hearst, this strategy was an unmitigated success. He later bragged that the Arbuckle case sold more copies of his San Francisco Examiner than the sinking of the Lusitania, which prompted the United States to join World War I. For Roscoe Arbuckle, the case and the publicity surrounding it led to an immediate fall from grace. His films were pulled from theaters and he became persona non grata in Hollywood. There was a genuine concern that the scandal would bring down the entire movie industry.

The Trials

During the indictment hearing, District Attorney Matthew Brady realized that the case against Arbuckle might not be as rock-solid as he hoped, but he certainly had no intention of backing down now, given how much publicity the case had already garnered before the trial even started.

His star witness was Maude Delmont, but you didn’t have to be Columbo to realize that her story was as phony as a three-dollar bill. For starters, it changed every time she said it. Then, during the hearing, she testified that Arbuckle had dragged Rappe into the room, even though it had already been established that he walked in after her. She kept insisting that the actor sexually assaulted the victim, even though this had also been proven false by the medical examination. And last, but certainly not least, some letters of hers revealed that she was plotting to extort Arbuckle for money. Unsurprisingly, Delmont was never called to testify during the actual trials.

The whole thing should have ended right then and there, but the judge concluded that Arbuckle could still be tried for first-degree murder, based on testimonies from a few other women who attended the party, who claimed that they heard Rappe say: “He did this to me” or something to that effect. At one point, Brady genuinely wanted to seek the death penalty in the case but, ultimately, the charge was lessened to manslaughter, which could still result in a ten-year sentence for the actor, if found guilty.

The first trial began on November 14, 1921. Most of the medical evidence went along the same lines – the injuries could have been caused by Arbuckle’s voluminous body, but they could also have been caused by something else such as STDs, cystitis, or an abortion.

Then came the testimonies from the women who said they heard Virginia Rappe accuse Arbuckle of attacking her. They were Betty Campbell, Alice Blake, and Zey Prevon, all of them actresses, models, or showgirls who attended the party. During cross-examination, Arbuckle’s defense team showed that all three of them had been intimidated by the prosecution to testify against the accused. If they didn’t, Brady would have hit them with a perjury charge. This little truth bomb resulted in a deadlocked jury 10-2 in favor of acquittal so, in early December, the judge dismissed them and a second trial was scheduled for mid-January.

The evidence during this trial went even more in Arbuckle’s favor. Zey Prevon testified that she never heard Rappe say anything and that she was pressured to give false testimony. The defense presented medical evidence that Rappe suffered from a chronic bladder infection called cystitis, which was aggravated by alcohol. Things were looking good for Arbuckle, but his defense team royally screwed the pooch when they decided to keep their client off the stand and not make any closing arguments. In their minds, this strategy was supposed to show confidence in how strong their case was, but it had the exact opposite effect on the jury. During the first trial, Roscoe’s affable and sincere testimony swayed some of the jurors, but now they found his absence indicative of guilt. They deadlocked 10-2 again, but this time in favor of conviction.

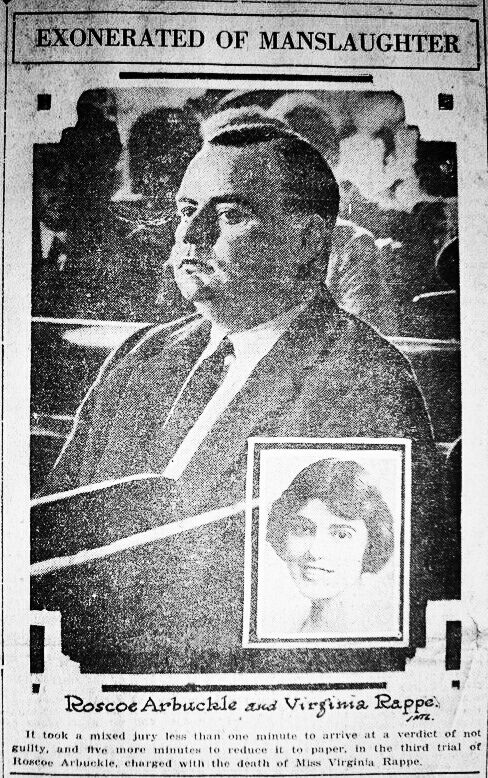

The third and final trial began on March 13, 1922. This time, Arbuckle’s attorneys took no chances. Point by point, they took every shred of evidence against their client and showed to the jury how it was either inconclusive or outright false. Their biggest gamble here was going after Virginia Rappe’s character, as they presented her as a promiscuous party girl, whom they accused of having several back-alley abortions that caused her health problems. This could have backfired badly if the jury took exception to them badmouthing a dead woman, but it didn’t. On April 12, the third jury went into deliberation for just five minutes before returning with a verdict – not guilty. That was not all, though, as they had prepared a statement which said:

“Acquittal is not enough for Roscoe Arbuckle. We feel that a great injustice has been done to him … there was not the slightest proof adduced to connect him in any way with the commission of a crime. He was manly throughout the case and told a straightforward story which we all believe. We wish him success and hope that the American people will take the judgment of fourteen men and women that Roscoe Arbuckle is entirely innocent and free from all blame.”

Canceled & Comeback

In the eyes of the law, Fatty Arbuckle was an innocent man, but that was not good enough for Hollywood. His case was one of several scandals that hit the movie industry in the early 1920s, and studio execs were worried that all this lurid publicity would remove the shine from its biggest stars, who were usually seen by the general public as larger-than-life figures above the problems and temptations of us puny mortals. Therefore, Hollywood would need to police itself and, thus, the Motion Pictures Producers and Distributors of America was born, today known simply as the Motion Pictures Association or the MPA.

The head honcho was Will Hays, a former politician and Postmaster General. A decade later, he would become notorious for adopting the Motion Picture Production Code aka the Hays Code, which acted as the de facto rulebook on what American movies were and were not allowed to show all the way up until the mid-1960s. But in the early 1920s, his main concern was to rehabilitate Hollywood’s image by getting rid of some of its most undesirable and immoral figures.

Fatty Arbuckle was at the top of the list. Even though he had been found innocent, just his association with such a big scandal was enough to get him blacklisted from the movie industry. Officially, Hays lifted the ban eight months later, but unofficially, everyone in Hollywood knew that they couldn’t touch the actor with a ten-foot pole.

Arbuckle’s personal life suffered as well. The trials left him heavily in debt. He became bitter and depressed and turned into an even bigger drinker. His first wife stood by him during the scandal, believing in his innocence, but she finally divorced him in 1925 and, although Roscoe remarried that same year to actress Doris Deane, his second marriage only lasted four years. But his biggest problem was finding a way to make a living.

Eventually, Arbuckle found some acceptance in Hollywood behind the camera, directing a few shorts each year under the alias William Goodrich. But these all saw limited releases and mainly featured unknown, up-and-coming actors, so none of them were big box-office hits. It wasn’t until 1932, a whole decade after the scandal, that Fatty Arbuckle was welcomed back to Hollywood’s bosom when Warner Bros. hired him to star under his own name in several comedy shorts. That same year, Arbuckle married his third wife, Addie McPhail.

On June 29, 1933, with the shorts finished, Warner’s offered him a contract for a feature film. It was everything that Arbuckle wanted, so he eagerly signed his name on the dotted line. As it happened, it was also his wedding anniversary, so that night he and Addie and some friends went out and painted the town red. Things were finally looking up once more for Fatty Arbuckle. That same night, the 46-year-old actor suffered a heart attack in bed and the King of Comedy died in his sleep.