On a chilly day in 1955, an unremarkable scene unfolded in Alabama that would change American history. Aboard a segregated bus, seamstress Rosa Parks was told to surrender her seat so a white man could sit down. It was a moment that had already played out thousands of times in Montgomery, a Southern city languishing under racist Jim Crow laws. But this time, things didn’t follow the script. Parks refused to move.

It was a decision that changed everything.

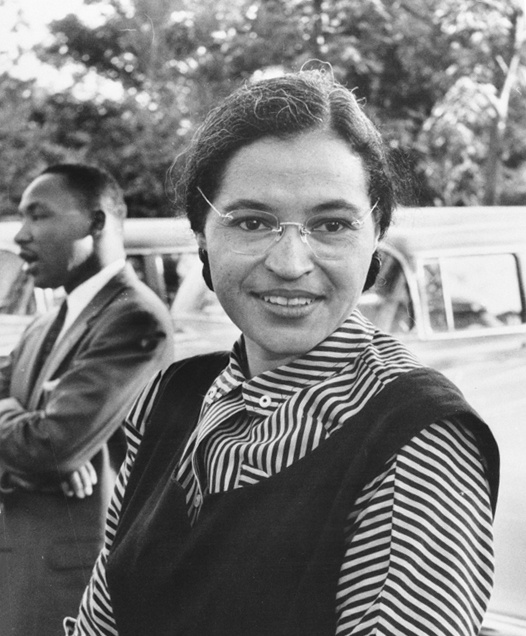

Removed from the bus and arrested, Parks became a lightning rod for the racial tensions crackling through the South. Led by Martin Luther King, Jr., Montgomery’s Black community boycotted the bus company for a staggering 381 days. It was African-American activism on a scale the US had never seen. It kickstarted the Civil Rights movement.

And it was all down to one woman.

Born at the nadir of US race relations, Parks grew up in a world where racism was a poisonous fact of life. But rather than keep her head low, she fought back. Even before she boarded that bus, she was an activist; a tireless pursuer of justice. Think you already know the real Rosa Parks? We beg to differ.

Strange Fruit

When Rosa Parks was born Rosa Louise McCauley on February 4, 1913, outside Tuskegee, Alabama, it was into a time and place designed to make her feel worthless. Ever since Reconstruction, the South had existed under Jim Crow Laws, forcing whites and Blacks to inhabit different worlds.

Famously, this meant African-Americans eating at segregated luncheon counters; drinking at segregated fountains; and living in separate communities.

But the discrimination went deeper.

In the world of Parks’s childhood, white people were “Mister or Mrs. Collins” – or whatever – while Black people were “James”, or “Malcolm,” or “Rosa”. As an African-American, you were expected to step off the sidewalk for a white person. To give up your seat on the bus. To never speak back.

Those who refused could find themselves fired from their jobs, left permanently unable to find work.

And that was just in the cities.

Out in the countryside, things could get much worse. When Parks was two years old, her parents’ business went under, her father left, and her mother was forced to move in with her parents – Rose and Sylvester Edwards – in rural Pine Level.

It was from her grandfather that young Rosa would get her first taste of activism. Sylvester Edwards’ had a mixed-race background, outwardly appearing to be white.

Yet his exterior masked a well of trauma.

As a child, Edwards had been a slave on a plantation.

He’d been mistreated even by the lamentable standards of the time, refused food until he nearly starved to death. Now a free man, he hated whites with a passion; refusing to show any deference, and often sitting out on the porch with a shotgun in his lap whenever white folk came nosing around.

It was a defiant, admirable attitude.

It was also one that could’ve gotten him killed.

Jim Crow was also the era of lynchings, when 4,400 people – three quarters of them African-American – were murdered by their white neighbors for the smallest perceived infractions. At their height, these lynchings took place out in the open; attracting huge crowds of smiling whites, who held their children up to get a good look at the mutilated body.

It was murder as a party, a carnival. One with a very clear message for Black people:

You could be next.

The same year Parks moved in with Sylvester and Rose Edwards, the Ku Klux Klan was reborn in Georgia, after four decades lying dormant. By 1916, it had spread to Alabama. By the time Parks was ten, it would boast 150,000 members in her home state.

For Parks, that meant a childhood lived beneath a shadow of violence.

As a girl, she would lie awake at nights, listening as the KKK went riding. She heard lynchings. Once, she even witnessed the Klan parade right past her doorway, a show of strength, of white impunity. On that occasion, Slyvester Edwards stood on the porch, shotgun loaded, calmly surveying the crowd. Just daring them to try something.

Yet, despite this backdrop of fear, Parks didn’t let herself be intimidated.

There’s a great story from when she was a girl, of a white boy who shoved her off the sidewalk. Parks calmly stood up, dusted herself off, and then shoved the white boy onto his ass.

The little wuss burst into tears. His mom shrieked at Rosa, demanding to know why she did that.

Parks calmly replied: “I didn’t want to be pushed, seeing how I was not bothering him at all.”

It’s kinda great that, even from this early age, we can see the fire burning in Rosa Parks. Her refusal to be a second-class citizen.

But make no mistake, it was a hard life. On her way to school, white kids would throw rocks at her. During the summers, she was forced to work all day picking cotton to help her family make ends meet. In short, Rosa Parks’ early life was just that of another poor, Black girl suffering under Jim Crow.

But this time, the system would meet its match.

Rather than let herself be ground down, Parks would wind up being the one who helped tear the whole rotten edifice down.

The Activist

Although she was intelligent, bad luck conspired to leave Rosa Parks with little in the way of formal education. Aged 11, she’d joined Miss White’s Industrial School in Montgomery, which had mostly-white teachers and mostly Black students.

But even this amount of mixing was too much for the city, which closed the school down.

Although Parks would start again at a new school, she’d soon be forced to drop out to care for her dying grandma and ill mother. As a result, the only job adult Parks was able to get was as a seamstress in a shirt factory.

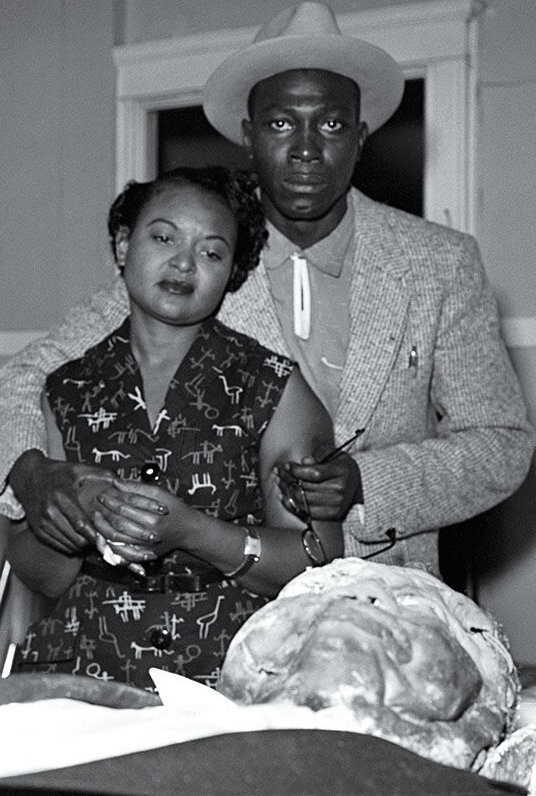

Still, something must’ve gone right, because a year later, in 1932, she was introduced to Raymond Parks.

A barber by trade, Raymond was also lacking in formal education. But that didn’t mean he was stupid. Always well dressed, and always read-up on every subject that mattered, Raymond was sharp as a pin, and he knew it.

In his spare time, he organized defense meetings to try and help the Scottsboro Boys – nine African-American teenagers who’d been falsely accused of raping white women. It was dangerous work, and most meetings took place around a table heavy with loaded guns.

But it was also the coolest thing 19-year old Parks had ever heard.

Raymond completely swept her off her feet. He proposed on their second date and, before the year had ended, the two were married. But if Parks had dreamed of getting involved in Raymond’s activism, her dreams would soon be crushed.

Raymond thought it too dangerous. The whole lot of them might get lynched at any time.

So Parks was forbidden from attending the Scottsboro meetings, instead sitting quietly on the porch as the men talked inside.

Still, Raymond was a supportive husband, encouraging her to earn her high school degree, something she did in 1933. After that, it was a series of menial jobs, the most-significant of which took place on an Army Base.

As it became ever-more apparent that another war was looming, the FDR administration had issued an order desegregating Army bases. When Parks began working as a secretary at Maxwell Field just outside Montgomery, she was shocked at life in a fully integrated environment.

She could sit next to whoever she wanted on the bus. Eat in a mixed canteen. Have white women serve her coffee.

She later claimed:

“You might say Maxwell base opened my eyes to how it could be”.

Yet the moment she stepped off the base every evening, it was back. Back to riding in the “Negro” section of the bus. Back to being a second class citizen. Back to a world where being Black meant always looking over your shoulder. As the decades ticked past and Parks turned 30, Raymond began to thaw on the idea of his wife doing activist work.

In 1943, they both joined NAACP, working long hours as volunteers.

For Parks, this was a crazy time.

NAACP charged her with recording racist violence across Alabama. This meant going out and collecting graphic accounts of beatings, whippings, and rapes doled out by whites.

The most horrific was the Recy Taylor case.

In September, 1944, a married Black woman was abducted by a gang of white men, who blindfolded her and took turns sexually assaulting her. In the aftermath, Parks was sent to take her story, only to be menaced by the local sheriff the entire time she was in town.

Although Parks succeeded in making Recy Taylor national news, she couldn’t change the world she lived in.

An all-white jury dismissed the case in five minutes. Although the names of Taylor’s abusers were known, they never faced justice.

Come 1947, Rosa Parks was famous across Alabama as a fiery activist. She even gave a speech that year at the local NAACP convention, for which she received a standing ovation. But it wouldn’t be her Civil Rights work that would make Parks famous.

It would be a single bus ride.

Waiting for the Spark

In the entire history of the Civil Rights movement, perhaps no other figure comes across as such a petty dick as James F. Blake. A Montgomery bus driver, Blake was charged with enforcing segregation on his vehicle. Or so he’d have you believe.

In reality, drivers were given discretion over how seriously they took these rules.

So while you got some jobsworths who always made Black people surrender their seats to whites, you also got some who turned a blind eye. But not James Blake. To those who’d ridden his bus, Blake was notorious for being a weapons-grade douche.

He forced Black people to come through the front door to pay, then made them get back off again and get back on via the rear door.

Not only that, he sometimes drove off as they were making their way to the back of the bus, leaving them penniless and without a ride in the freezing cold. Congratulations, James Blake. You’re being discussed on a channel that has made videos on Stalin, and you’re still somehow the pettiest tyrant we’ve ever encountered.

Rosa Parks actually had a run-in with Blake during her early days as a NAACP investigator.

In 1943, she boarded his bus through the front door, paid for her ticket, then refused to get back off and go to the rear door. The incident ended with Blake grabbing her arm and shouting at her until Parks ran from the bus. Given what we know of Rosa Parks today, it can seem odd that she was involved in a separate bus incident 12 years earlier.

But that’s only because we’re looking with hindsight.

In 1943, or even in 1952, there was no evidence that the spark for Civil Rights might come from segregated buses. 1943 Parks wasn’t all like “Great! I’ll do this again in a decade and watch the world change!”

It was only in 1953 that activists started to see the potential for buses to become a powderkeg.

That’s because 1953 was the year Baton Rouge showed what could be done. That June, a sudden reversal in bus desegregation in the Louisiana capital exploded into direct action. Black churches organized an 8 day boycott of the bus system, costing the company thousands of dollars.

Although the gains made by the end of the boycott were few, they made activists’ ears prick up across the South.

If it could be done in Baton Rouge, why not in – say – Montgomery?

By now, it was clear something was building below the surface of Southern society, a volcano about to erupt. In 1954, the Supreme Court ruled in Brown v Board of Education that schools must be desegregated. While this was a victory, it was one met with immediate backlash. Just a year later, 14-year old Emmett Till was lynched in Mississippi for answering back to a white woman.

Clearly, whites were still ready to use violence to keep hold of their privilege.

But by now, the Alabama NAACP was already committed to finding a test case for bus desegregation. They nearly succeeded in November, when teenage Claudette Colvin refused to give up her seat to a white person and was arrested and roughed up.

But NAACP discovered she was both pregnant and unmarried, and decided not to pursue her case. Knowing the broadsides that would be launched against whoever headed the test case, they simply couldn’t risk using someone without a spotless reputation.

Another near-miss was Jo Ann Robinson, an educator from Montgomery.

Not long after the Claudette Colvin thing, Robinson got on a bus and deliberately sat in a “whites only” seat. It seems she was trying to spark a confrontation, to get arrested.

But when the driver started screaming and swearing at her, her nerve broke. She left the bus.

And so December, 1955 arrived with the activist community still waiting for the spark. Still waiting for the test case that would give them their shot to blow Jim Crow wide open.

Fortunately, Rosa Parks was about to become that spark.

Battleground

December 1, 1955 was a chilly day in Montgomery. It was also a busy day, at least if your name was Rosa Parks.

By now, Parks was working in a department store fixing dresses. With Christmas approaching, it was already a busy time, and Parks had her NAACP work on top of that. She spent her entire coffee break making NAACP calls, and her lunch hour meeting with a lawyer to discuss a case.

By the time she left the building at 5pm, she was tired as a dog.

The line at her regular bus stop was crazy, so she ran some errands. By the time she came back, the queue had thinned out a little. A bus pulled up. Parks got on, and took a seat beside a African-American man in the middle section known as “No Man’s Land.”

These were the undesignated seats, the ones theoretically reserved for neither whites nor Blacks.

In practice, though, the drivers would often eject Black people from these rows when whites were forced to stand. Especially if the driver just happened to be an epic dick.

Care to guess who was driving Rosa’s bus that day?

As the bus moved on, it got busier. Two more Black people came to sit in the same row as Parks. Eventually, the bus was so full that a white man was forced to stand. It’s at this point that James Blake did what James Blake did best.

The driver came to the row Parks was sat on, and told all four Black people to move.

When everyone refused, he threatened to call the cops. One by one, the other three wearily stood and went to the back.

But not Rosa.

Instead of leaving, she slid across to the window, showing she had no intention of moving. To this day, it’s uncertain what was going through her head. The Rev. Jesse Jackson once claimed she was thinking of poor, lynched Emmett Till:

“Rosa said she thought about going to the back of the bus. But then she thought about Emmett Till and she couldn’t do it.”

The popular story is that she was just tired – from work, from being treated like garbage. Another view is that Parks was all too aware the NAACP needed its test case, and had decided it would be her.

Blake ordered her to get up. Parks refused. He threatened to call the police, to which she calmly replied:

“You may do that.”

So Blake did.

What’s interesting is that the policemen were just as unhappy with Blake’s bull poop as everyone else. They tried to defuse the situation, but when neither Blake nor Parks would budge,they reluctantly led Rosa Parks away. Parks later said they asked her:

“Why didn’t you just stand up?”

“I don’t know,” she replied, “why do you push us around?”

“I don’t know. The law’s the law.”

After that, it was a trip to the local jail. There, Parks used her phonecall to notify Raymond, who freaked out, terrified she’d be assaulted in her cell. But no. All that happened was that Parks was fingerprinted, and then spent the night behind bars.

As she slept, though, the wheels were already turning.

Through Raymond, NAACP and other groups found out about the arrest. Across the night, some 35,000 flyers were distributed across Montgomery’s Black communities, calling for a bus boycott. Children brought the flyers home from school. Black churches urged their congregations to boycott the buses that Monday.

One of the preachers doing that urging was a 26-year old called Martin Luther King, Jr.

New in town, and virtually unknown even in Alabama, Doctor King had no intentions of becoming a household name.

Yet the stage was now being set for his own dizzying rise to prominence.

By Sunday evening, the citizens of Montgomery were ready. As he went to bed that night, MLK confided that he’d consider the boycott a success if only 60% of Black riders participated. Little could he have known that the real figure would exceed his wildest dreams.

Direct Action

On Monday, December 5, 1955 Rosa Parks went on trial.

The proceedings were fairly undramatic. Parks was fined $10 and ordered to pay $4 court costs – a pretty small sum even in 1955.

But the real action was happening outside.

That morning, Doctor King had awoken to a jaw-dropping sight. Nearly all the buses in Montgomery’s Black areas were empty. Far from stopping at 60% of riders, the boycott had pulled in nearly 100%.

And so began the most-legendary boycott in US history. For 381 days, Montgomery’s Black citizens avoided the buses, using creative means to get to and from work. At first, cabs charged African-American riders only ten cents, but the City passed a spiteful law forcing them to charge a minimum of 45.

So the Black community organized a community taxi system, which made scheduled rides around town, acting like a sort of back-up bus.

But while the boycott affected the whole of Montgomery, it affected Rosa Parks most of all. Usually, when the story of Parks is told, it stops with her refusing to get off the bus, then skips straight to that famous photo of her riding an integrated bus after the boycott.

There’s a good reason for that.

Rosa’s life during the boycott was Hell. At work, none of her Black colleagues would talk to her, lest they get reputations as troublemakers. She was fired for her activism in January, 1956. At the same time, Raymond’s work brought in a new rule forbidding people to discuss Rosa Parks, so he quit in disgust.

Penniless, unable to find new work, the two were then left traumatized by slander and death threats.

First, the slander.

Barely had the boycott started than fake news started crawling out the woodwork. Segregationists said anything they could about Parks, that she was a Communist, that she was actually Mexican, that she had a car and didn’t even need to ride the bus.

It was the same old crap you still see today: slander the messenger so you don’t have to hear the message.

But in 1955, some people went further.

Parks and Raymond started receiving death threats; a steady steam that caused Raymond to have a minor breakdown. Then, on January 30, a segregationist bombed Martin Luther King’s home while his children were inside.

Luckily, no-one was hurt, and MLK used that act of violence to advance his message of peaceful protest, telling supporters:

“I want you to love our enemies. Be good to them, love them, and let them know you love them.”

But Parks wasn’t some saint. She was just a regular woman, and the violence terrified her.

Nor was her test case even going ahead. Although Parks was the face of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, her case was actually dropped by organizers when they realized they had three better ones they could use.

All that violence, all those threats, and Parks wasn’t even part of the lawsuit anymore.

Finally, in November of 1956, the case made its way before the Supreme Court. In a major decision, the Justices ruled against segregated buses. Although the city of Montgomery tried to appeal, they were refused.

On December 20, Montgomery was issued with a formal paper ordering an end to segregation on public transport.

The very next day, the Boycott lifted.

Martin Luther King and Rosa Parks both separately rode the new, integrated bus system that day. Parks was even photographed, looking wistfully out the window, a white man sat behind her to show the old system was now gone.

They’d done it. Against all the odds, one lone protest by Rosa Parks had shaken up the whole of Montgomery. It had shown Black people what they could achieve with community action.

It was everything everyone had dreamed of. A happy ending.

Wasn’t it?

Aftermath

Normally, the story of Rosa Parks ends here, with Montgomery’s bus services integrated and the Civil Rights movement gaining steam. But sadly life isn’t a prepackaged Lifetime movie where the credits roll and everyone goes skipping off into the sun.

Life after the bus boycott was hard for Parks and Raymond. Unbelievably so.

Thanks to Rosa’s notoriety, neither of them were able to find work in Alabama. Even Civil Rights organizations wouldn’t hire them. Most were run by men, who took one look at Parks and said:

“This isn’t work for women.”

By 1957, Parks couldn’t even afford medicine to treat her stomach ulcers. She tried moving to Virginia to work at the Hampton Institute, but they wouldn’t give her lodgings so she quit.

On top of economic worries, the threats of violence hadn’t receded with the boycott’s end.

There was a real, urgent danger to Parks’s life so long as she remained in the South. In 1957, her family convinced her to relocate to Michigan for her own safety. But while that took care of the danger, it didn’t change the economic side one little bit.

By 1960, Jet magazine was describing Parks as a:

“tattered rag of her former self — penniless, debt-ridden, ailing with stomach ulcers, and a throat tumor, compressed into two rooms with her husband and mother.”

It was a painfully low point in Parks’s life, an undeserved end.

Luckily, this was also the moment things began to turn around.

The Jet magazine profile seemed to stir some consciences. NAACP paid off Parks’s medical bills, allowing her to get her cancer operated on. Shortly after, Raymond finally managed to find work, and soon the couple were back on sound financial footing.

That meant they lived to see Lyndon B. Johnson sign the Civil Rights Act into law in summer of 1964.

It meant Parks was able to join the campaign to get John Conyers elected to Congress, in part by convincing Martin Luther King to endorse the candidate – something King rarely did.

As a reward, Conyers gave her a salaried position in his office, one she kept right up until her retirement.

Interestingly, by this point, Parks was tired of King’s philosophy of non-violence. She preferred Malcolm X, once saying:

“If we can protect ourselves against violence it’s not actually violence on our part. That’s just self-protection, trying to keep from being victimized with violence.”

Sadly, Parks would live to see both of these icons assassinated: Malcolm X in 1965, and MLK in 1968. Ten years later, in 1977, Raymond died of cancer. And, suddenly, Parks was all alone. Sad as this was, though, Parks also lived long enough to see herself transformed into an icon.

Right into the late 1970s, she was still receiving death threats from segregationist whites.

But at some point, the tide began to turn. Things began to change. In 1996, she was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom by a white president who’d grown up in the segregated South.

Three years later, in 1999, she was also awarded the Congressional Gold Medal.

By the time Parks died, on October 24, 2005, she was globally famous. Her story was told in textbooks. Kids heard about her in school. After death, her body was placed in the Rotunda on Capitol Hill so people could pay their respects – only the second African-American to ever be afforded that honor.

Eight years later, in 2013, a statue of her was added to the Rotunda – the third statue of a Black person to ever be placed in the building.

Today, Rosa Parks is no longer a mere person, but an icon. One who encapsulates an entire era, an entire struggle.

Children learn about her. Her name is everywhere, on buildings, streets.

And yet, the real Parks is sometimes almost forgotten. In telling her tale over and over, Parks has been reduced in the public consciousness to a symbol.

Easily understandable as the tale of the tired woman who refused to give up her seat may be, it’s important to remember that the sanitized version leaves out all the human parts. Leaves out the violence Parks grew up with, the financial misery she suffered for holding her ground, all the things that would’ve broken a lesser-person.

It’s uncomfortable to hear, because we all like a fairytale. We’d all like to believe Parks was recognized as a hero from day one, rather than hearing that taking a stand nearly destroyed her.

And yet, in a way, this bleaker version just makes her that much more inspiring.

Here was someone who wasn’t a saint, wasn’t just a tired working woman with sore feet; but an activist. Someone who saw the degradations suffered by the Black community and decided she had to speak out – no matter what the consequences.

By recognizing this darker side of her story, hopefully we, too, can be inspired to do the right thing. To fight the good fight.

Because, as the tale of Rosa Parks proves, one person really can change the world.

Sources:

History Chicks Podcast on Rosa Parks: http://thehistorychicks.com/episode-141-rosa-parks-revisited/

American National Biography: https://www.anb.org/view/10.1093/anb/9780198606697.001.0001/anb-9780198606697-e-1501309

Biography: https://www.biography.com/activist/rosa-parks

History: https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/rosa-parks

NPS: https://www.nps.gov/features/malu/feat0002/wof/rosa_parks.htm

Some context: https://www.historyextra.com/period/20th-century/from-rosa-parks-to-martin-luther-king-the-boycott-that-inspired-the-dream/

Parks at NAACP: https://www.history.com/news/before-the-bus-rosa-parks-was-a-sexual-assault-investigator

After the boycott: https://www.history.com/news/rosa-parks-later-years-aftermath

https://www.biography.com/news/rosa-parks-life-after-montgomery-bus-boycott

Jim Crow Laws: https://www.khanacademy.org/humanities/us-history/the-gilded-age/south-after-civil-war/a/jim-crow

Lynchings: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2018/apr/26/lynchings-memorial-us-south-montgomery-alabama

Rosa Parks Misconceptions: https://time.com/4125377/rosa-parks-60-years-video/

Baton Rouge Bus Boycott of 1953: https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=1304163

Parks in Virginia: https://www.loc.gov/exhibitions/rosa-parks-in-her-own-words/about-this-exhibition/detroit-1957-and-beyond/working-at-virginias-hampton-institute/

Link to Emmett Till lynching? https://nmaahc.si.edu/blog-post/emmett-tills-death-inspired-movement

The Klan in Alabama: http://www.encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/h-3221

Montgomery County lynchings: https://eu.montgomeryadvertiser.com/story/news/2018/04/25/equal-justice-initiative-eji-alabama-lynchings-elmore-bolling/524675002/