It is the dawn of the 14th century. The Kingdom of Scotland is in chaos. Over a dozen nobles have made a claim for the throne, threatening to plunge the country in civil war. Meanwhile, the King of England is making a play for control of his northern neighbor, hoping to take advantage of the power vacuum to unify all of Great Britain under a single ruler.

But, as Sun Tzu said, “In the midst of chaos, there is also opportunity.” Robert the Bruce, member of a noble Scottish family, certainly took this to heart. Using a mix of dogged determination, tactical acumen, and political savvy, the Bruce fought off all internal rivals and then made war on England, throwing the English out of the country and establishing himself as the one true ruler of Scotland. By doing this, he not only became the most important King in the history of Scotland, but his actions had far reaching consequences that continue to be felt today.

The Great Cause

Robert was born on July 11th, 1274, the eldest son of Robert de Brus, the Lord of Annandale, a powerful noble in the Kingdom of Scotland. Little is recorded of his early life, though we can assume he was brought up in much the same way as most nobles of the period were: educated in multiple languages, the arts and skills of war, and the politics and customs of the royal court.

In 1286, the King of Scots, Alexander III, died suddenly after falling off his horse. His only living descendant was a young granddaughter, Margaret, who was the daughter of the King of Norway. As was customary when a child ascended to the throne, a council of regents, called the Guardians of Scotland, were appointed to govern the country until Margaret was old enough to rule herself. But it wasn’t to be: Margaret died in 1290, at the age of 7, never having set foot in the kingdom she was supposed to rule.

Now the Guardians were faced with a huge problem. The 250 year long reign of the House of Dunkeld had ended with the death of Alexander and Margaret, and a new monarch needed to be crowned. But who? A total of 13 nobles made claims on the throne of Scotland, one of which was Robert de Brus. The Guardians were afraid that any attempt to resolve the matter internally would lead to civil war, so they asked King Edward I of England to arbitrate in the dispute.

Edward, known as “Longshanks” because at 6’ 2”, he towered over most men of his day, was eager to take advantage of the chaotic situation for his own ends. Before agreeing to the arbitration, he forced the Guardians to make concessions to him, stopping just short of declaring Scotland a client state overlorded by King Edward. Edward then set up a court of 104 auditors to decide who should be declared King of Scots.

The process that followed was known as “The Great Cause.” For two years, the court heard arguments from the various claimants. The court decided in favor of John Balliol (pronounced Bay-Lee-Ole), Lord of Galloway, in 1292, but the real winner had been Edward.

Conflict Begins

Over the next four years, Edward continued to assert pressure on Scotland, forcing further concessions, and relations between Edward and John Balliol soon began to deteriorate. The Bruces at this time sided with Edward in the disputes, they hated Balliol and considered him a usurper. This put them into conflict with the Comyn (pronounced Cumming) clan, staunch supporters of Balliol and one of the most powerful families in the country.

In 1296, the Bruces were living in Carlisle Castle, an English fort that had been given to them by King Edward, after being driven out of Scotland by the Comyns. In March of 1296, Carlisle was attacked by members of the Comyn faction, who hoped to eliminate their rivals. The attack failed, but the incursion onto English soil gave Edward an excuse to invade Scotland and take over the whole country personally. He deposed John Balliol and imprisoned him in the Tower of London.

Edward believed that Scotland had been pacified and returned south to deal with the French. But the trouble in the north was only just beginning. In May 1297, a rebellion against English control of Scotland began, led by William Wallace and Andrew De Moray. Robert, ordered by Edward to go with his retainers and suppress the rebellion, had a change of heart enroute and when he arrived, joined with the Scots instead.

Wallace and De Moray won a great victory over the English at the Battle of Stirling Bridge in July, but the Bruce, along with most of the other nobles, weren’t there. Instead they were engaged in intense negotiations with King Edward.

William Wallace fell from grace after he was defeated by Edward at the Battle of Falkirk in July 1298, and in his place two new Guardians of Scotland were appointed: Robert the Bruce and John Comyn of Badenoch. This attempt at national unity backfired, as the two men were mortal enemies and couldn’t agree on anything. Early in 1302, Robert switched sides again and swore loyalty to King Edward. It’s likely he did this for two reasons: the nobles in Scotland were increasingly coalescing around the idea of John Balliol being returned to the throne, and if that happened, Robert would lose his chance to wear the crown himself. Also, it looked as though Edward was winning the war, and Robert believed the smart play was to bide his time, perhaps even wait until the 63 year old Edward died, before making his move.

Outlaw King

The Bruce was now playing a very delicate game: outwardly, he supported Edward’s hold on Scotland. Behind the scenes, however, he was rallying support for his own bid for the throne of Scotland. A significant obstacle presented itself in the form of John Comyn, Robert’s rival, considered the most powerful noble in the country. In the summer of 1305, shortly after the capture and execution of William Wallace, the Bruce made a deal with Comyn: that Comyn would renounce his claim to the throne in exchange for all of the Bruce land in Scotland if he supported a revolt led by the Bruce. But some time later, Comyn betrayed the Bruce’s intentions to King Edward, and Robert was forced to flee the English court to avoid arrest.

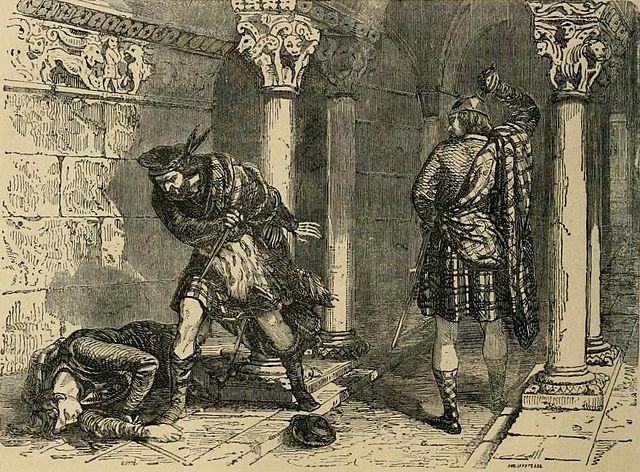

Outraged, Robert set a meeting with Comyn at the Greyfriars Monastery in Dumfries on February 10th, 1306. During the meeting, the Bruce accused Comyn of treachery, and the two men came to blows. In a fit of rage, Robert drew his dagger and stabbed Comyn, his retainers rushed in and killed the man.

Immediately, Robert realized the gravity of what he’d done: he had shed blood in a church, the ultimate sacrilege. Furthermore, he’d killed one of the most powerful men in Britain, guaranteeing the animosity of Comyn’s allies and relatives on both sides of the border. The die had been cast, he needed to make his play for the throne now.

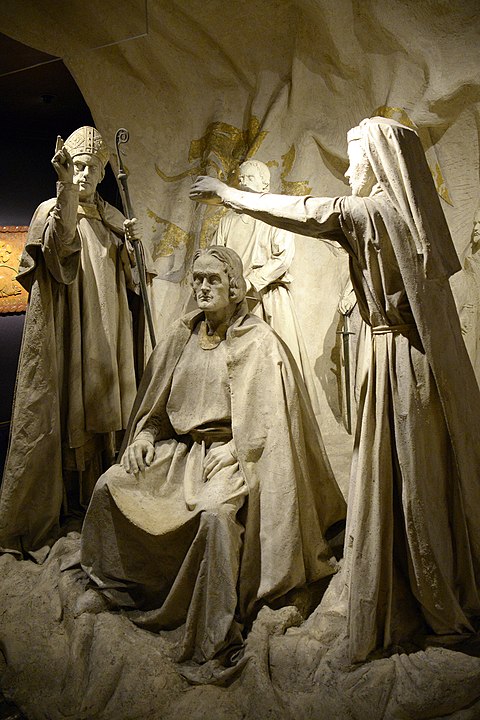

Robert went to Glasgow and met with Robert Wishart, Bishop of Glasgow. Wishart was a friend and ally of his, and granted him absolution for the killing. Wishart also made arrangements to have Robert crowned king. Six weeks later, at Scone, the traditional coronation location for Scottish kings, the Bruce was crowned Robert I, King of Scots, with all the usual pomp and ceremony.

In England, the news was met with outrage. Edward believed that Robert had committed an egregious sin by murdering his rival in a church, and now he was compounding that sin by claiming a crown that Edward believed belonged to him. He called Robert an outlaw, and sent an army north under command of his son, the Prince of Wales, to crush him. The Prince was flying the dragon banner, a symbol that the usual rules of chivalry did not apply: no prisoners were to be taken, any enemies captured were to be executed. What had been a political conflict would now become very, VERY personal.

Disaster at Methven

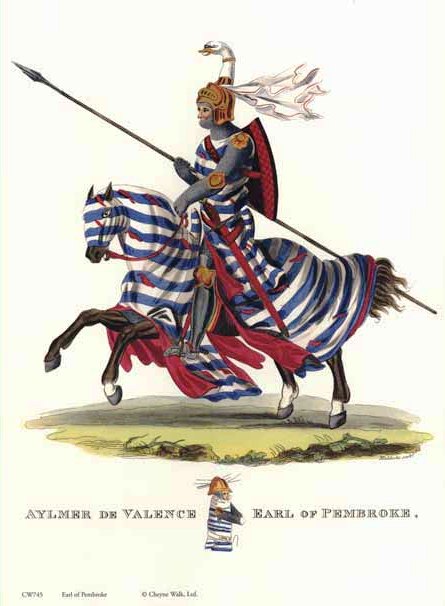

Robert had not heard yet that he’d been excommunicated by the Pope or that King Edward considered him an outlaw. He raised an army of about 4,500 men and marched to Perth, where an English force of about 3,000 was garrisoned, commanded by one of Edward’s trusted lieutenants, the Earl of Pembroke. Robert called on Pembroke to come out of Perth and do battle, a chivalric tradition, but Pembroke claimed that it was too late in the day and he would fight tomorrow. So Robert’s army made camp for the night about six miles away, near the village of Methven.

While the Bruce’s army were settling in for the night, suddenly, the English fell upon them in a surprise attack. Sneak attacks and night fighting in general were not in keeping with chivalric code, but since the English claimed that Robert was an outlaw, they didn’t have to act chivalrous towards him or any of his followers.

Taken completely by surprise, the Scots stood no chance. Of the 4,500 that made up Robert’s army, at least 4,000 were either killed or taken captive and then executed. The Bruce was forced to flee with a small group of men, having lost many of his most loyal followers.

More bad news followed: the Prince of Wales captured Kildrummy Castle in September, where Robert’s wife, daughter, and sisters were sheltering. The Prince had Robert’s brother Neil, the commander of the castle, executed, and took the women captive, taking them to England.

Rebound

Robert spent that winter in hiding, likely in the Hebrides, islands off the western coast of Scotland. The year had been a disaster for him, and he seemed destined for obscurity as leader of yet another failed rebellion against English rule in Scotland. But even at this low point, Robert was convinced of the rightness of his cause.

The Bruce realized that before he could take on the English again, he needed to deal with his enemies in Scotland, the Comyns. Because most of his supporters were gone, he couldn’t hope to win in traditional battle. Instead, he would rely on hit and run tactics, to loot and burn and destroy support for his enemies from the civilian population.

In February 1307, Robert’s forces came back to mainland Scotland. Initially, things didn’t go well, as one part of his army was destroyed, and two more brothers, Thomas and Alexander, were killed. Robert went to his family’s ancestral lands at Carrick, to raise men and supplies for his campaign. The English went after him, with an army of 3,000 commanded by Pembroke, who had beaten the Bruce the year before. But this time Robert was ready for him: at Loudoun Hill on May 10th, the King trapped Pembroke’s army in a narrow causeway surrounded by marshland and killed hundreds of English knights, forcing the rest of the army to retreat in confusion. With the English army subdued, Robert could turn his attention to the Comyns.

Meanwhile, King Edward decided to go north himself and fight the Bruce. But while traveling north, the king became ill with dysentery. He died on July 7th at the age of 68. The Prince of Wales was now crowned King Edward II. This was good news for Robert: Edward II was definitely not his father. The younger Edward was not as intimidating, and more importantly, he was not as interested in running the affairs of state himself, leaving the country in care of subordinates, particularly his favorite, Piers Gaveston, who is alleged to be Edward’s lover.

While the new King of England headed south to consolidate his hold on power in England, Robert headed to the north of Scotland, where the Comyns had their base of power. Over the course of the next 18 months, he systematically crushed all internal opposition to his authority, capturing and destroying every stronghold the Comyns had, burning and killing the inhabitants.

War with the English

Now that the Comyns were defeated, the Scots rallied to the Bruce in droves. It was time to take on the English who still occupied most of the south of Scotland. Over the course of ten years of war, Robert had noticed a pattern in the English campaigns in Scotland: they would invade in the spring, and then they’d leave again in the winter, leaving castles relatively lightly garrisoned to secure their foothold for the next spring’s campaign.

So he decided on a novel strategy for the time: when the English armies invaded, he refused to go out and fight them, melting his army into the hills and engaging in guerilla style warfare (though it wasn’t called that at the time). Then, when the English left, like the ocean tide going back out, Robert came down from the hills and attacked their castles. From 1309 to 1313, using this method, he took one English fortress after another, pushing the English systematically out of the country without ever fighting them in open battle.

By 1314, the only major castle left in English hands in Scotland was Stirling, and Robert’s brother Edward laid siege to it. Robert now felt secure enough in his power that he issued a proclamation that any noble in Scotland who hadn’t yet acknowledged him as King of Scots would lose their lands in one year’s time.

Meanwhile, the commander of the English garrison at Stirling, Philip de Mowbray, recognizing the hopelessness of his position, made an agreement with Edward Bruce that unless he was relieved by June 24th, he would surrender the castle.

King Edward Marches to Stirling

If Stirling was lost, the English would lose any control they had left in Scotland. So Edward II, long distracted by squabbles with his own nobility, decided to act: he raised a massive army for the time: 15,000-20,000 men, and headed north into Scotland to attempt to relieve Stirling. Robert, recognizing that everything he’d done so far could be undone by this, knew he had to stop Edward before he reached Stirling. He marched his army, about half the size of the English, to a position a few miles south of Stirling, near the Bannock Burn, a fast flowing stream.

On June 23rd, the English arrived. An advance screen of cavalry came upon one of the Scottish schiltron formations, a defensive phalanx of pikemen that was the typical Scottish battle formation, blocking the road to Stirling. King Robert was with them, rallying his troops. One English knight, Henry de Bohun, charged at the king and challenged him to single combat. This was the kind of thing Robert the Bruce relished, so in spite of the danger, he accepted. King Robert dodged de Bohun’s lance and split the young knight’s head open with his battle axe, killing him instantly. The only thing Robert would say about the fight later was that he was upset he’d broken his favorite axe.

The English cavalry commander, the Earl of Hereford, had just witnessed his nephew being slain by the Scottish king. Enraged, he attacked the Scottish infantry, unaware he’d been led into a trap. The ground around the road had been dotted with pit traps, covered by branches, so that when the English cavalry tried to spread out into attack formation, dozens of men and horses suddenly disappeared, falling into pits with wooden stakes planted at the bottom. Then the schiltron formation of the Scots advanced, killing many of the tightly packed English horsemen who had no room to maneuver. Hereford was forced to retreat. Meanwhile, an attempt by another contingent of English cavalry to encircle the Scottish position was opposed by the other part of Robert’s army, and the English were again compelled to retreat.

The vaunted English heavy cavalry, the kings of the medieval battlefield, had been defeated by peasant infantrymen armed with spears. The English morale took a huge dip at the end of the first day’s battle. A Scottish knight in the English army, Alexander Seton, deserted to the Scots during the knight and told Robert that he should attack the demoralized English.

Battle of Bannockburn

The next day, June 24th, dawned, and King Edward began forming his lines to charge the Scottish position in the woods in front of him, considerably more cautious than the day before. Then, to his surprise, the Scottish infantry began emerging from the woods and marching towards the English position across the open field.

It seemed suicidal, and the argument on the English side wasn’t whether to charge the Scots or not, but who would have the honor of leading the attack. The Earl of Gloucester, who had been accused of cowardice by King Edward for suggesting the battle be postponed at one point, determined to win glory for himself and charged, accompanied by many knights. They ran right into the Scottish schiltron, who, instead of giving way, stood fast, and the cavalry was impaled on the long pikes. Gloucester and most of his contingent were dead within minutes.

Edward now ordered a general advance. English understanding of Scottish tactics was that the schiltron was a defensive formation, and thus wasn’t mobile, when the troops started to march, the formation would break up. But the Bruce had trained his infantry to use the schiltron as an offensive as well as defensive formation. Once again, when the English cavalry charged the Scots, they were met by a wall of spears that stopped their attack cold.

The English archers, who might have been able to break up the Scottish formations, were ineffective: the cavalry, mounted on their tall chargers, were in the line of fire, and the archers had to stop after they started hitting their own men. The Scottish infantry pushed the English back, trapping them between the Bannock Burn on one side and the Pel Stream on the other. The cavalry had nowhere to maneuver and began to break ranks. Deciding that the battle was lost, Edward fled along with 500 royal bodyguards. This triggered the collapse of the entire English army into a chaotic rout. It is estimated that over 10,000 English soldiers were killed during the battle and the retreat back into England, fewer than 5,000 made it out of Scotland alive. It was the greatest triumph in Scottish military history.

Aftermath

In exchange for the English nobles he captured at Bannockburn, Robert negotiated the release of his wife, daughter, and sisters after eight years of captivity. Stirling Castle quickly fell, and all of Scotland now belonged to the Bruce. Now the Scots were the ones conducting raids into northern England, and even mounted a serious invasion of Ireland, which lasted for years before they were defeated in 1318.

The war with England continued until 1327 when Edward II was deposed by his wife, Isabella, and their 14 year old son was crowned Edward III. Robert forced the issue by attacking northern England and defeated the young Edward at the Battle of Stanhope Park on August 4th, 1327. Finally the English were forced to the bargaining table, and Robert and Edward signed the Treaty of Edinburgh-Northampton in 1328. The English formally recognized Robert the Bruce as King of Scotland and renounced all claims of overlordship to the country. The war, which had consumed Robert’s entire adult life, was finally over.

Around the same time, the Pope lifted the order of excommunication against Robert from over 20 years before. But unfortunately for the Bruce, he wasn’t able to enjoy the peace for long. A lifetime of campaigning had taken its toll on the king, and he grew ill in 1327 with an unknown illness, possibly leprosy or tuberculosis. This illness claimed his life on June 7th, 1329, at the age of 54.

His five year old son David succeeded him to the throne of Scotland and had a turbulent reign, but it was his grandson, Robert II, the son of the Bruce’s daughter Marjorie, who had the lasting impact on history. Robert II was the first king of the House of Stuart that would rule Scotland for over 300 years until King James VI of Scotland was also crowned King of England in 1603. 100 years later, the two countries were formally joined together as the Kingdom of Great Britain. Today, Queen Elizabeth II can trace her ancestry all the way back to Robert the Bruce, who is her 19th great grandfather.

It is interesting to note that, despite all of the English attempts to subjugate Scotland in the 13th and 14th centuries, it ended up being a Scot that sat on the throne of England and unified the two countries that way. But we’re sure that’s just the way Robert the Bruce would have wanted it.