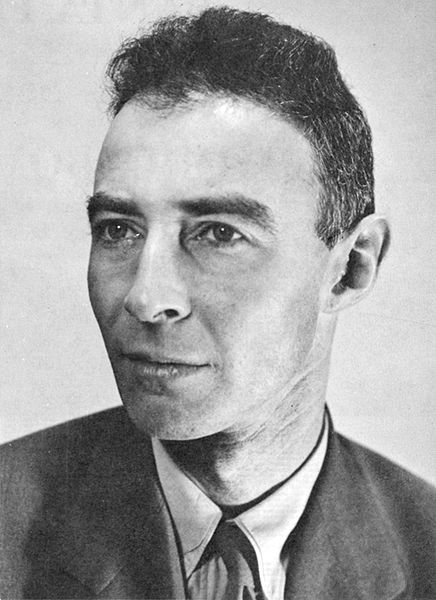

His was the brain that oversaw the most destructive project in all of human history. It won a war by unleashing unimaginable horror, in the process catapulting the world into the nuclear age. For his efforts, he was accused of being a Russian spy and side-lined by his government. In this week’s Biographics, we take a look at the life and work of J. Robert Oppenheimer.

Beginnings

Julius Robert Oppenheimer was born on April 22nd, 1904 in New York City. His father, Julius, had fled Jewish persecution in Europe as a teenager. His mother, Ella, was also Jewish, with her family having been in New York for several generations. The couple were married in 1903, with Julius, who was known as Robert, being their first child. A second son, Frank came long in 1912, when Robert was eight.

The family lived in an upscale apartment on New York’s West Side. Julius had built a successful textile importing business and Ella was a painter. They employed a cook, servants and a chauffeur. Life for young Robert was structured and formal with dinners requiring a suit and tie.

Scientific Beginnings

When Robert was five years of age, the family took a vacation to Germany. There he met his grandfather who gave him a collection of minerals. He was mesmerized by the stones, leading to a lifelong obsession with rock collecting. When he was eleven, he joined the New York Mineralogical Club. A year later he presented his first scientific paper.

Julius sent his son to the best school he could find, the New York School for Ethical Culture. Robert attended from second grade right through to college graduation. The focus of the education was science, literature and ‘moral law’. Robert was an A Grade student who completely devoted himself to his studies. As a result, he didn’t have much of a social life. Friends were few and far between. In fact, according to his high school English teacher, he once said . . .

I’m the loneliest man in the world.

Robert was extremely socially awkward as a teenager. From the start he considered himself the smartest guy in the room and this led to an arrogance which was off-putting to his peers. They were also put off by his prim and proper nature.

Discovering Physics

After graduating from high school, he attended Harvard in order to pursue serious scientific studies. He majored in chemistry but soon fell in love with physics. He was admitted into graduate studies in physics and began studying under the famous experimentalist Percy Bridgman. Oppenheimer knew straight way that this was what he wanted to do with his life. He took a rigorous course load each semester, which allowed him to graduate in three years.

At that time, the American colleges couldn’t compete with the physics laboratories in Europe. The science world was enthralled with the physics revelations of Albert Einstein and, for any serious up and coming American physicist, crossing the Atlantic was an essential requirement. In 1924, Oppenheimer was admitted to Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge, England. This was one of the most renowned nuclear physics labs in the world. The lab was under the direction of Ernest Rutherford, who had already won the Nobel Prize for splitting the atom.

Oppenheimer was assigned to a team of researchers under the leadership of J.J. Thomson who, in 1897, had discovered the electron. It was the ultimate setting for a budding physics genius but Oppenheimer quickly realized that he wasn’t cut out for it. He and experimental physics just didn’t gel. He was unable to keep up with the required workload and almost suffered a mental breakdown. By now he had developed a habit as a chain-smoker and often neglected basic hygiene and nutritional practices as he got bogged down with his work. But try as he may, he was unable to keep up with the required workload.

An Unstable Mind

A depressed and overwhelmed Oppenheimer went to see a psychiatrist, who told him that he was suffering from schizophrenia. The prognosis was not good, with long-term institutionalization being the standard treatment. Oppenheimer refused to believe the diagnosis. He took a vacation to Paris with his friend Francis Fergusson. However, he wasn’t exactly good company, being consumed with his own melancholy. Fergusson tried to cheer him up by breaking the news that he was going to marry his girlfriend. When he heard this, something snapped inside Oppenheimer’s fragile mind and he leaped upon Fergusson and proceeded to strangle him. Fergusson was able to fend him off, but from then on became convinced that his friend had serious mental problems.

Finding his Calling

In 1926, Oppenheimer took up a position at the University of Gottingen in Germany. This was the center of theoretical physics in Europe and Oppenheimer landed right in the middle of a revolution in the field. He found himself rubbing shoulders with and learning from the premier names in quantum physics, including Enrico Fermi, Wolfgang Pauli and Werner Heisenberg.

Here, finally, Oppenheimer, found his perfect fit. In 1927 he received his Ph.D in physics. Over the next two years he established himself as one of the leading physicists in Europe, publishing sixteen papers on quantum physics.

American physicists had been left behind by the European quantum physics revolution. Many of the professors refused to accept the new, counterintuitive theories that went against the grain of everything they had known. This left a slew of young, eager physicists, excited about what was happening in Europe, left out in the cold. Oppenheimer saw himself as the vehicle by which the European advances in quantum physics could be introduced to American physicists.

Oppenheimer the Teacher

His first position back in the States was as a professor at the University of California at Berkeley. He now had a head brimming with knowledge and lecture halls filled with students eager to learn from him. The problem was that he didn’t know how to teach. His social awkwardness didn’t help. He would become tongue tied in front of his students. When he did speak his ideas would come out as a jumbled mass of words that simply served to confuse those in attendance. By the end of his first semester, there was just one student remaining who was taking his class for credit.

Fortunately, things got better. He applied himself to his teaching and slowly improved his ability. He managed to cut out the verbiage to pare down his lectures, making them both understandable and exciting. As a result, the students, who referred to him as ‘Oppie’, began flocking to his lectures. Within a couple of years, a cult of personality had developed around him and he had his own groupies who were known as ‘Oppie’s boys’. He relished the attention and gave his time generously to his students. Often discussions would be held after class, with students even ending up at his home. The subject usually morphed from physics to science, art and literature and would be fueled by generous quantities of alcohol.

While teaching at Berkeley, Oppenheimer continued his physics research. He published more papers on quantum physics, but did not make any ground-breaking discoveries. He did, however, convert the Berkeley lab into a world class facility, establishing the new quantum physics as a legitimate science in America.

Oppenheimer totally immersed himself in his work and the adulation of his students. He did not own a phone, a radio or even read the newspaper. When his mind wasn’t on physics, he would be studying Hindu mythology or the ancient classics. As a result, he was totally divorced from the outside world. When the Great Depression struck following the 1929 Wall Street crash, he was none the wiser, being insulated from the effects thanks to a trust fund.

Broadening Horizons

It was the effect that the depression had on the lives of his students that made Oppenheimer aware of its devastating impact. This brought him an awareness of just how much political and economic events could affect people’s lives. This awareness was strengthened as he began to take notice of what was happening in Nazi Germany. Having Jewish heritage himself, he looked on with great concern at the rise of Hitler.

Yet, it took a woman to transform Oppenheimer’s political concerns into action. Jean Tatlock was a graduate student who was studying for a degree in psychology. She was also a Communist Party member. Tatlock introduced Oppenheimer to the world of radical politics. He joined a number of institutions aligned with the Communists, though there is no evidence that he actually became a card-carrying member of the Communist Party. However, in 1936, his brother Frank moved to California and did join the party.

Oppenheimer fell in love with Tatlock and they pursued a tempestuous relationship between 1936-39. With the end of his contact with Tatlock, his interest in Communism waned and, by the 1940s, he had become disenchanted with it, mainly due to hearing reports of what life was really like in the Soviet Union. Yet, despite his later assertions that his flirt with Communism was nothing more than a boyhood fling, accusations that he was a Russian sympathizer would dog him for the rest of his life.

In the wake of his break-up with Tatlock, Oppenheimer began a relationship with a woman named Kitty Harrison. There was, however, one problem – Kitty was married. She was in fact, into her third marriage, with her husband being a British doctor. She soon divorced the hapless doctor, with Oppenheimer becoming her fourth husband on November 1st, 1940.

![The Trinity test of the Manhattan Project was the first detonation of a nuclear weapon, which lead Oppenheimer to recall verses from the Bhagavad Gita: "If the radiance of a thousand suns were to burst at once into the sky, that would be like the splendor of the mighty one "..."Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds".[110]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/f/fc/Trinity_Detonation_T%26B.jpg)

War

The bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7th, 1941, changed the lives of senior physicists in the United States profoundly. Overnight their theoretical research was being called upon to help win the war. The first challenge presented to physicists was to develop a radar system. The country’s top physicists gathered at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Radiation Laboratory, ready to throw themselves into what they thought would be the great work that would win the war.

Then, in September 1942, work began on a program that proved to be far more impactful than the Radar project – the development of a nuclear bomb.

In 1939, three German physicists had discovered nuclear fission, which enabled a massive amount of energy to be released when neutrons struck a uranium nucleus. Among the first to recognize the massive destructive potential of this technology if it could be harnessed in the form of a bomb were two Hungarian scientists. They made it their mission to warn the President of the United States that he needed to develop such a bomb before the Germans did. But these minor scientists could not get anyone to listen to them. It was only when they secured the support of the world’s most famous scientist, Albert Einstein, that they were able to get President Roosevelt’s attention.

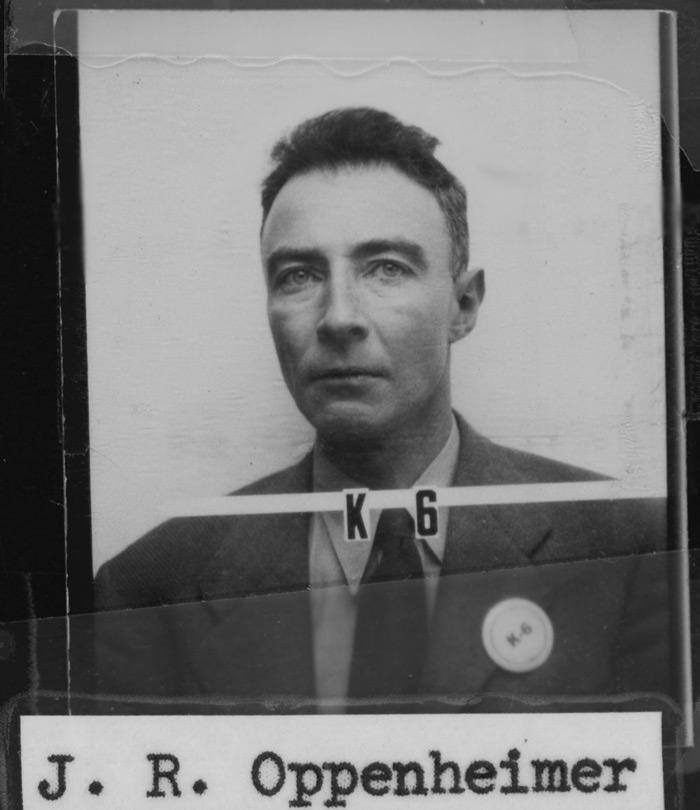

The Manhattan Project

As a direct result of a letter he received from Einstein, Roosevelt created the Advisory Committee on Uranium. The Committee begin to stockpile uranium but didn’t move fast enough for Roosevelt. It was soon dissolved and replaced with the National Research Defense Council (NRDC). The council was put in the hands of the army with Brigadier General Leslie Groves having oversight. The project was given an innocuous name so as not to give away its purpose – Groves called it the Manhattan Project.

![Oppenheimer and Leslie Groves in September 1945 at the remains of the Trinity test in New Mexico. The white canvas overshoes prevented fallout from sticking to the soles of their shoes.[188]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/7/7e/Trinity_Test_-_Oppenheimer_and_Groves_at_Ground_Zero_002.jpg/1024px-Trinity_Test_-_Oppenheimer_and_Groves_at_Ground_Zero_002.jpg)

The Manhattan Project was not based in one single location. Rather, there were a number of laboratories located around the country, each tackling a specific aspect of the project. The biggest challenge was the creation of the bomb itself and this task was to be overseen by Oppenheimer. The base of the operation was Los Alamos, a deserted area in the north-central part of New Mexico. This location, which was selected by Oppenheimer himself, was to be his home for the next three years.

An old boy’s school was renovated to serve as a base camp with a number of barracks being moved in to serve as homes for the physicist who would work on the project.

With the facility ready, Oppenheimer travelled the country in search of the best scientific minds to help him build the bomb. In addition to former students he called on top physicists, a number of whom were exiles from Nazi Germany. If he was concerned that he would find the people he needed, he needn’t have been. He originally estimated that he would need thirty people. But scientists from all over the country were energized by the opportunity and, by the end of the war, there were more than 6,000 people living at Los Alamos.

Despite the primitive living conditions and the obsessive desert heat, the scientists relished their time at Los Alamos. Many of them had their families with them and spent their time off hiking and skiing all over the Southwest. What they weren’t keen on was the seemingly over the top secrecy imposed by the military who were ever present. Every scientist was under constant surveillance and none more so than Oppenheimer himself. During his time at Los Alamos, the government tapped his phone, opened his mail and had men trail him everywhere.

As overseer of the project, Oppenheimer had to, not only contend with the invasion of his own privacy, but to mediate between the often feisty scientists and the military. He constantly reminded the physicists to keep the big picture in mind – they were involved in a once in a lifetime struggle for the very salvation of mankind.

By February of 1945, the brains at Los Alamos had come up with two designs for the atomic bomb – they were codenamed Little Boy and Fat Man. Little Boy was a uranium-based bomb while Fat Man used plutonium. The scientists were so confident in the design of Little Boy that they deemed it unnecessary to test. But Fat Man did require testing.

Oppenheimer decided to test Fat Man near Alamogordo, New Mexico. It was a sixty mile stretch of desolate landscape from north to south and forty miles east to west. To carry out the explosion safely, they had to ensure that the wind was traveling in the right direction. If it wasn’t, radioactive dust and debris could travel over residential areas. They had to wait for what seemed like forever to get just the right conditions. During this time, Oppenheimer was wound up with stress that things would go wrong and they would unleash destruction upon the citizens of New Mexico.

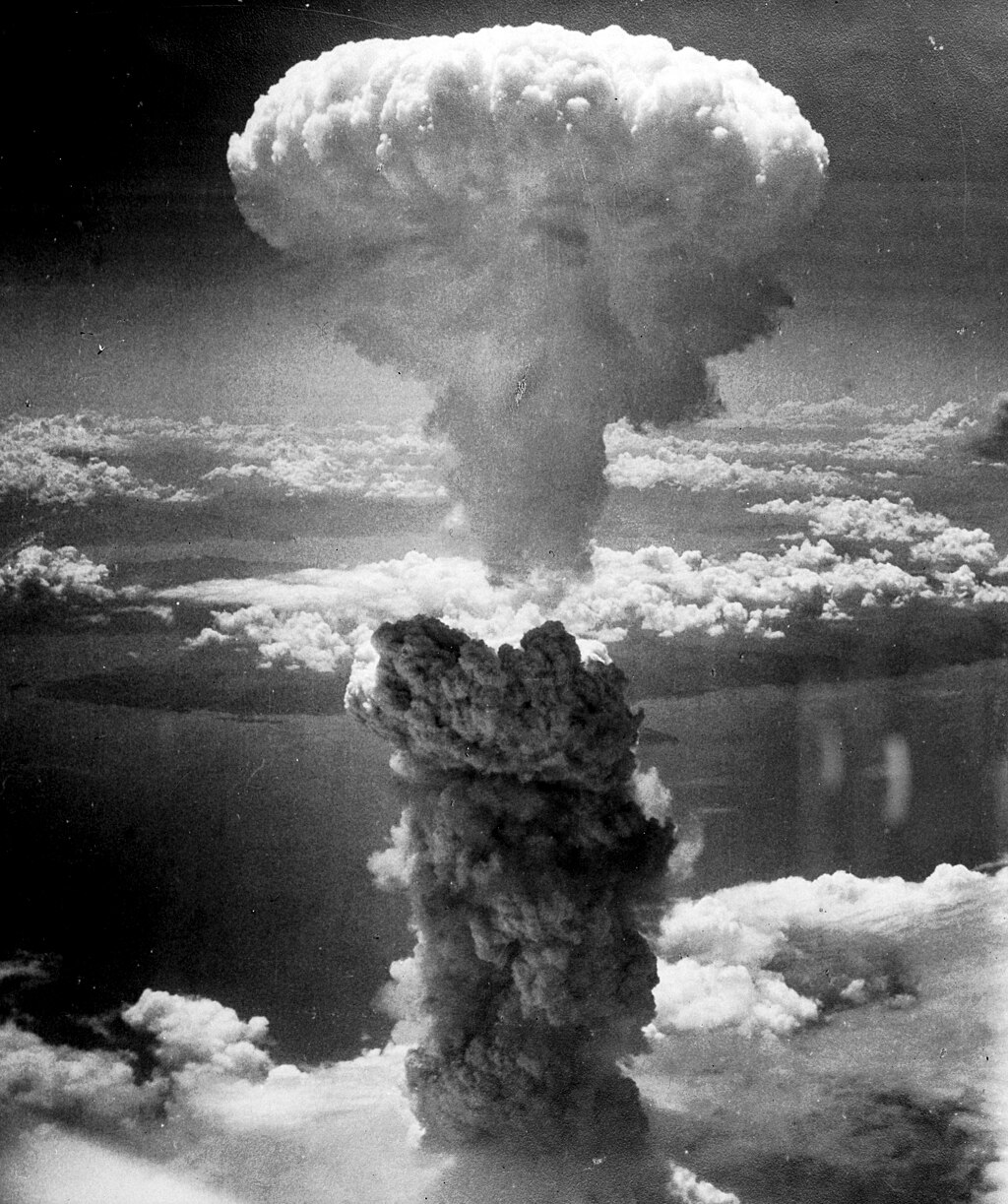

Finally, the conditions were right. The explosion took place on July 16th, 1945. The resulting flash was visible from three states. The mushroom cloud rose 38,000 feet into the air, while the crater that was blown into the ground was half a mile wide.

The other scientists gathered at the site cheered enthusiastically in the wake of the explosion. But not Oppenheimer. He found the situation apt to quote from the Hindu text, the Bhagavad Gita . . .

Now I am become Death, the destroyer of worlds.

Dropping Bombs

The decision to make use of the bombs was now in the hands of President Harry S Truman. After much soul-searching he decided to use it on the Japanese in order to force them to surrender. On August 6th, 1945, the B-29 bomber Enola Gay dropped Little Boy over the city of Hiroshima. 90 percent of the city’s buildings were instantly destroyed, along with sixty-six thousand people. However, the immediate Japanese surrender was not forthcoming. On August 9th, Fat Boy was dropped on the city of Nagasaki, causing a further 42,000 deaths.

The double whammy was too much. On August, 14, 1945 Emperor Hirohito announced the Japanese surrender. When he first heard that the bombs had brought about the desired effect, Oppenheimer rejoiced, along with the rest of the nation. On later reflection, however, he took in the realization of just what he had unleashed upon the world.

Post War Activities

On October 16th, 1945 Oppenheimer relinquished his position at Los Alamos. He returned to Caltech before taking up a position as director the Institute for Advanced Study at Princeton University. But, after three years of excitement, power and cutting-edge research, he found University life too mundane.

With information about the Manhattan Project now in the public domain, Oppenheimer became a household figure, with his face appearing on the cover of Time magazine. He now used his position of prominence to lecture around the country on what he felt the United States should do with their new-found nuclear technology. From his unique perspective he appreciated both the technological achievement as well as the killing potential that it had unleashed. He now felt a responsibility to ensure that its future use was for good and not evil. He advocated for international sanctions on nuclear power, but to no avail. At the same time, he appreciated that having nuclear power was a huge advantage to the American defense program. So, rather than trying to stop it, he worked to try to keep it from getting out of control.

![Presentation of the Army-Navy "E" Award at Los Alamos on October 16, 1945. Oppenheimer (left) gave his farewell speech as director on this occasion. Robert Gordon Sproul right, in suit, accepted the award on behalf of the University of California from Leslie Groves (center).[92]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/87/Army-Navy_E_Award.jpg/1920px-Army-Navy_E_Award.jpg)

Fall from Grace

Meanwhile, the Americans rushed to find a response to the Russian bomb. Discussions were held about a new type of bomb, one that was a thousand times more destructive than those that had been dropped over Japan. It was to be a bomb that was powered by hydrogen. Oppenheimer was opposed to the hydrogen bomb, fearing that it would become a weapon of genocide. But President Truman decided to go ahead anyway and the hydrogen bomb codenamed Mike was exploded in 1952.

In November, 1953, the FBI received a letter from a former government official alleging that Oppenheimer was a Soviet spy. It was enough to bring the full power of the McCarthy Communist witch hunt down on him. Oppenheimer’s security clearance was immediately revoked. A three-man investigation was than undertaken. As it progressed, it became obvious that he was really being investigated for his opposition to the Hydrogen bomb project rather than his supposed ties to the Soviets. The resulting report permanently shut Oppenheimer out of any involvement in government affairs due to what it termed ‘the proof of fundamental defects in his character’.

Following the humiliation of his ouster from the government, Oppenheimer returned to the Institute for Advanced Study. In 1963, with the McCarthy red scare long in the past, the government offered an olive branch to Oppenheimer by awarding him the Enrico Fermi Award for Excellence in nuclear research. Still, he never fully recovered from the humiliation of the 1950’s. Four years later, on February 18th, 1967, he died of throat cancer. He was 62 years of age.

Sources:

Oppenheimer: The Tragic Intellect by Charles Thorpe

Oppenheimer by Tom Morton-Smith

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vm5fCxXnK7Y&t=13s