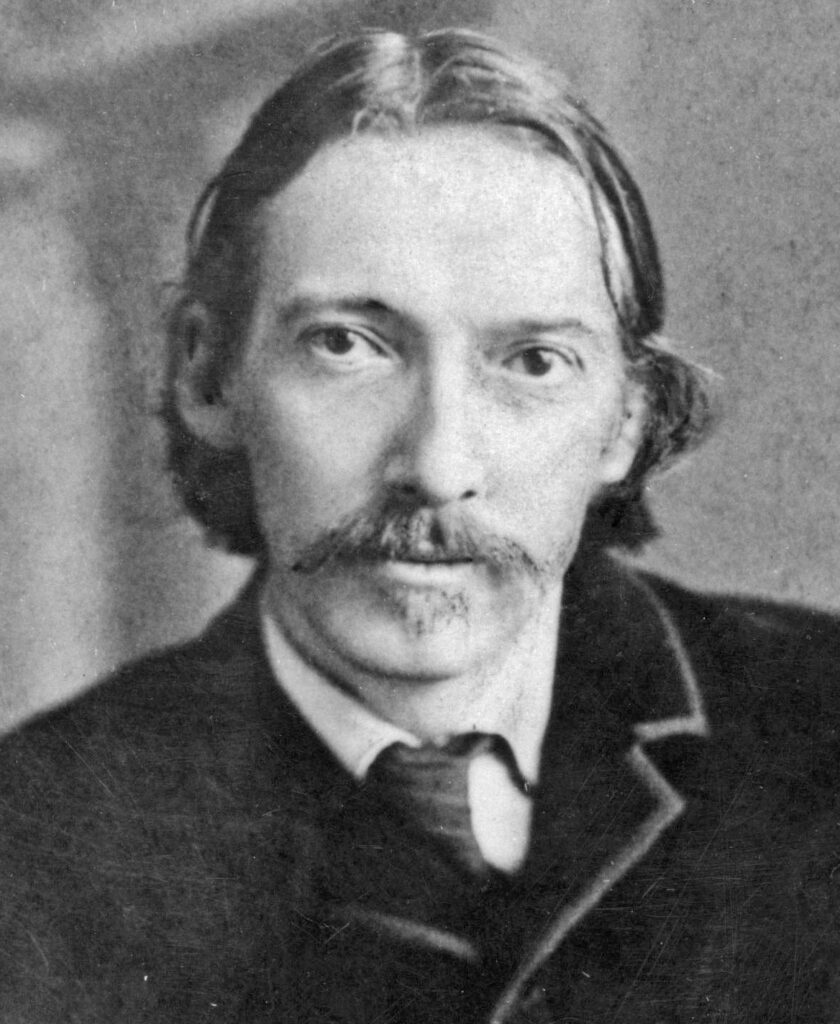

Robert Louis Stevenson holds a special place in the hearts and minds of many readers. He often served as an introduction to real, grown-up books. Stories like Kidnapped and Treasure Island may be considered classics, but they’re also full of adventure and intrigue — the sort of stories that make you wish you were one of his characters, sailing the high seas, looking for buried treasure, fighting to reclaim your legacy.

His stories are undoubtedly all classic works of literature, and while many are told against the backdrop of very real events, like the Jacobite rising of 1745, there’s also something about them that speaks to a sense of grand imagination, a longing for adventure, and a deep sense of justice.

It’s time to pull out your spyglass and take a peek at the life of this 19th-century Scottish writer. You’ll find there’s a reason he was so good at telling some of the tallest tales imaginable, setting them against epic, historical backdrops. For much of his life, his world was only what he could see — or dream — from his sickbed.

An ill child who lived through imagination

Childhood often lays the groundwork for a lifetime, and for Robert Louis Stevenson, that was definitely the case. He was born on November 13, 1850, the only child of middle-class parents. His mother came from a family of high education, growing up in a world of church ministers and lawyers. His father had a job that most people would consider not only respectable, but pretty cool: he was an engineer, and he was involved in building numerous deep-sea lighthouses along Scotland’s coast.

For much of his childhood, the family lived at 17 Heriot Row in Edinburgh, and it’s a place anyone with a healthy respect for Georgian architecture would truly appreciate. Built sometime between 1802 and 1806, it was still fairly new when the Stevenson’s only child roamed the halls; it’s easy to imagine a young boy running up and down the stairs, jousting his way down the hallways, staging adventures in the garden, perhaps turning the giant enamel bath his father had installed into a swath of ocean filled with monstrous creatures.

Unfortunately, Stevenson’s childhood was very different. When his parents welcomed him into the world, he was a perfectly normal, healthy boy, but it wasn’t long before he started suffering from severe respiratory problems. Those problems would shape not only his childhood but the rest of his life.

Stevenson spent a lot of time during his formative years fussed over by anxious parents and cared for by a nurse who would end up having a major impact on his adult life. He wasn’t — as one might expect — hunting for buried treasure in the back garden, or pretending to ride imaginary horses up and down the streets of the city. Instead, he spent much of his time swathed in blankets and shawls, doted on by the adults around him, learning that he was very fragile.

Historians never quite decided just what it was he suffered from. The original diagnosis was tuberculosis, but today, it’s suspected that modern medicine would come up with a diagnosis of bronchiectasis, which is a series of continuous infections resulting from damage done to the lining of the bronchial tubes — a condition often said to be made worse by the presence of dust and air particles, and often starting with a childhood illness. If that’s the case, there’s a sad addendum to his sickly childhood: his well-meaning caregivers were always afraid of drafts making him ill, so the windows in the home were always closed. Would some fresh air have made a difference? It’s impossible to say.

What we do know is that Stevenson’s childhood nurse had a profound impact on him. Her name was Alison Cunningham, but everyone called her Cummy, and she lived with the household for a full two decades. By all accounts, she loved the young Stevenson as if he were her own son, and in addition to being a caregiver, she was also a storyteller. True, Stevenson was often confined to his home, or to the strictly regimented life of a health spa, but only in the physical sense. Cummy entertained her young charge with a variety of tales. Her firm Calvinist beliefs formed the backbone of many of the stories she regaled him with, but she also told tales of ghosts, ghouls, and other supernatural specters.

Nights were particularly difficult for Stevenson. From a young age, he suffered from insomnia and was often kept awake for all hours by illness and feverish vision. Frequently be lulled back to sleep by his father, who would sit by his side and invent conversations with imaginary people. The conversation was always droll but always soothing, sending the young boy drifting off to sleep, escorted by made-up characters and conversations plucked from thin air.

And sometimes, it was Cummy who filled Stevenson’s sleepless nights with stories, fueling his nighttime delirium. If you look at Stevenson’s childhood through a more modern lens on parenting, and it’s easy to put some sort of blame on the shoulders of his guardians. He was also susceptible to nightmares, and there’s one school of thought that suggests the mix of Cummy’s religious doctrine, ghost stories, and the fevers he frequently ran fueled those nightmares and those sleepless nights. But it also fueled something else: his imagination and imagination isn’t always kind.

Still, given that he started “writing” his first work at the tender age of six — he dictated a tale called “A History of Moses” to his mother — it’s safe to say that from a very young age, he was enthralled by the power of the story. His caretaker must receive at least some of the credit for this

It’s been suggested, too, that Stevenson’s illness didn’t just inspire him, but magnified his ability to write. As he grew older and more established, his letters began to mention the phenomenon of splitting into what he called “myself” and “the other fellow.” It was, he said, a side effect of the high fevers he so frequently suffered from, and it’ll sound familiar to anyone who’s read the tale of Jekyll and Hyde. “Myself,” he said, was his rational mind, while “that other fellow” was the side of him that held the darkness and the creativity. For Stevenson, that wasn’t scary. He loved it, it drove him, and he believed it helped him create the works we all still love today.

Life as a writer? You’d better have a backup plan

With the benefit of hindsight, it seems like a given that Stevenson was a natural writer. But that belief wasn’t always there, and his parents certainly didn’t want their only son throwing his life away on what is often a gamble of a career choice. By the time he was a teenager, though, Stevenson was confident that his future career path would involve the written word. His father, on the other hand, hoped he would become an engineer — the third such professional in the family.

Resigned, Stevenson enrolled in the University of Edinburgh to study engineering. It was quickly clear that going to university just wasn’t for him, and instead of spending his time attending lectures and pouring over his studies, he was more interested in making friends.

CREDIT: Theoden sA – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0

And here is where one of those strange coincidences happens. One day, as the story goes, Stevenson was simply walking down a street in Edinburgh when he bumped into another student. They got to chatting and ended up heading to the tavern for a few hours instead of going to class. The other student was JM Barrie, who would go on to write Peter Pan.

Beyond his adventures in Neverland, Barrie wrote of Stevenson that “Some men of letters, not necessarily the greatest, have an indescribable charm to which we give our hearts.”

A backhanded compliment, maybe, but other writers who met Stevenson at the same time and over the course of his career were completely taken with him. Edmund Gosse would later describe their first meeting in London like this: “As twilight came on, I tore myself away, but Stevenson walked with me across Hyde Park, and nearly to my house. He had an engagement, and so had I, but I walked a mile or two back with him. The fountains of talk had been unsealed, and they drowned the conventions. I came home dazzled with my new friend.”

One of the things that constantly struck those who met him was the contradictory duality present with him. Outwardly, he was incredibly frail. At 5-foot-10, he weighed only 116 pounds when he was 23 years old. When he spoke, though, he could easily capture the attention of a room. So it wasn’t entirely surprising when, in 1871, he did what many people would be terrified to do: he told his parents that he wasn’t going to follow in the family’s footsteps after all. Stevenson was going to be a writer.

Anyone who has ever dropped a bombshell like that on their parents can probably imagine how well that went over, but Stevenson’s parents weren’t completely opposed to the idea. They only insisted that Stevenson have a backup plan, so his parents asked him to study law, just in case the writing thing didn’t take off like he thought it would. He agreed, completing his law degree in 1875.

Love comes when you least expect it

It was just a year after graduating from law school that Stevenson’s life would drastically change. It started with his want for adventure; imagination was wonderful, after all, but he wanted to experience all the things he had dreamed about as a child. He first planned a canoe trip, beginning in Antwerp and ending in the north of France. Afterward, he headed off to a small town south of Paris, called Grez-sur-Loing. It wasn’t a random choice: the town was a favorite among the artistic and bohemian communities, and Stevenson already had a cousin living there, Robert Alan Mowbray. But it was also here that he would meet the love of his life.

Fanny Van De Grift Osbourne ended up in France after a fairly epic story of her own. When she was only 17 years old, she married an American military officer named Samuel Osbourne. Following the American Civil War, he headed off to seek his fortune in the silver mines of Nevada. He told his family his wife and daughter to join him, and they did.

Fanny didn’t like it the West at all. The Indiana native bore two more children, but her husband proved less than honorable. Sick of his cheating and his prolonged, mysterious disappearances, she packed up her children and left Nevada for Belgium.

This, too, was 1875. It was a time when most women wouldn’t have even considered such a thing, and the first obstacle they faced showed just how different times were. She and her daughter had planned on studying art in Antwerp but were told that women were not allowed to enroll in art schools. They moved on to Paris, but when her youngest son took ill and died, she retired to a small town in the countryside with her remaining children.

The town was, of course, the small artists’ community of Grez-sur-Loing, and that’s where she met Stevenson. They had a lot working against them. She was 11 years older than him; she had two children already; technically, she was still married to Osbourne. Stevenson, meanwhile, was fresh out of law school, had no job or career to speak of, and was still trying to figure out just how he was going to turn this whole writing thing into a livelihood. He had already written one book based on his earlier canoe trip, but one book won’t support a family.

Stevenson courted Fanny for two years. They enjoyed each other’s company, but the presence of another man in her life eventually forced Fanny to reconsider the one she’d left behind. She decided to return to California to give her husband another chance.

Abandoned by the woman he loved, Stevenson set out on another adventure — one that would become the inspiration for his second book, Travels with a Donkey in the Cevennes. For 12 days, he hiked the Cevennes with the help of a donkey who carried his baggage for him; he covered 120 miles of difficult country, which wasn’t just ambitious — it was outright dangerous.

Not everyone was a fan of the book, particularly because of the treatment of its titular character. When Stevenson bought his donkey, he named her Modestine, and by the time the 12 days were over, her value had been cut in half. Getting her to move along involved Stevenson delivering regular blows, and one critic summed up just how horrible it was, writing, “Raw legs and bleeding skin do not move him in the least.”

The trip had been taken at least in part in an attempt to heal a broken heart, but their story wasn’t over yet. In 1879, Stevenson received a telegram from California. Fanny was sick, her husband hadn’t changed, and she regretted ever leaving Europe. In a grand gesture that really is the stuff of a classic romance novel, Stevenson hopped on a ship in Glasgow and sailed for America. After landing in New York, he took a train all the way from the east coast to the west, and by the time he reached her in Monterey, California, the journey had taken a terrifying toll on his already fragile health. But for Fanny and her children, it seemed worth every sacrifice. By December of 1879, she had formally divorced Samuel Osbourne. Less than six months later, she married Stevenson.

Those early months were filled with extreme highs and lows. Stevenson and his new bride stayed in Napa Valley for a time, where he wrote The Silverado Squatters. But it was also there that he became seriously ill, as he developed a new symptom: he began to cough up blood.

Was it a death sentence… or did it make life worth living?

Stevenson’s poor health never really rebounded after the long trip from Scotland to California, and for the remainder of his life, the little family moved several times in an attempt to find a climate more agreeable to his delicate constitution. The first stop was England, where they lived until 1887 — save for the winters, which were spent in the south of France.

Stevenson supported his family by writing essays and bits of travel journalism, providing readers with his thoughts on dogs, umbrellas, and a litany of other common observations. However, this time is more associated with the publication of his major career highlights: he wrote and published Treasure Island in 1883, plus The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, and Kidnapped, both in 1886.

Treasure Island, in particular, came from a brilliant moment of inspiration. The family was away on holiday, staying in a small Scottish town, and the day was rainy and dreary. The story varies a bit — some say Stevenson was the one to first draw the map of a mysterious island, while his stepson, Lloyd, would later claim it was he who drew it. Either way, a map was drawn, and Stevenson began to name points of interest: Spyglass Hill, Skeleton Island… then, someone added three red crosses and a title of Treasure Island, and the foundation of one of the literary world’s most beloved pirate tales was formed.

And here’s a little aside — the map included in various editions of Treasure Island was not the original. That original map was lost, somewhere between submitting it to the publisher and getting the book printed. While Stevenson did redraw the map himself, he was reportedly never quite happy with it… and the fact that the original map for Treasure Island is actually lost is pretty darn appropriate.

In 1887, Stevenson’s father died; with no real reason to stay in Britain any longer, he and his family left — first for a year in America, then to the South Pacific. Eventually, they reached Samoa, where they decided to stay, at least for a moment. In Samoa, he not only wrote a lot — often from the confines of a sickbed — but he also became a treasured member of the community. He immersed himself in local politics and activism and was even given the title of Tusitala, or the teller of tales.

Originally, Samoa had just been another stop on the itinerary, with no real intention of staying there, but Stevenson gradually came to the conclusion that the climate would be good for his health.

With his mind made up, Stevenson bought a 300-acre estate and settled in to the place that Steveson and Fanny considered to be their first real home. Sadly, it would also be their last.

Samoa’s Setting Sun

On the surface, their lives should have been idyllic. Locals and travelers — particularly those who had made the journey to Samoa from Scotland — were always welcome at the estate. They celebrated everything from birthdays to American Thanksgiving; food and songs were more plentiful than the guests. They had around 15 servants working to keep the estate running, and Stevenson himself found solace in working the land. He took to gardening and weeding, in particular, once writing, “Farming is amusing; literature, save in results, is intolerably stupid. […] Nothing is so interesting as weeding.”

There was an unhappy undercurrent, though. Fanny aspired to be an artist of her own, and when he told her that she had “the soul of a peasant,” she was extraordinarily offended. Stevenson had meant it as a compliment — watching gardeners and botanists work to plant and cultivate the land had made him wonder if writing was real work; physical labor, it seemed to him, was a much more worthy endeavor. But Fanny didn’t take it that way, and the artistic anxiety she had always struggled with only got worse.

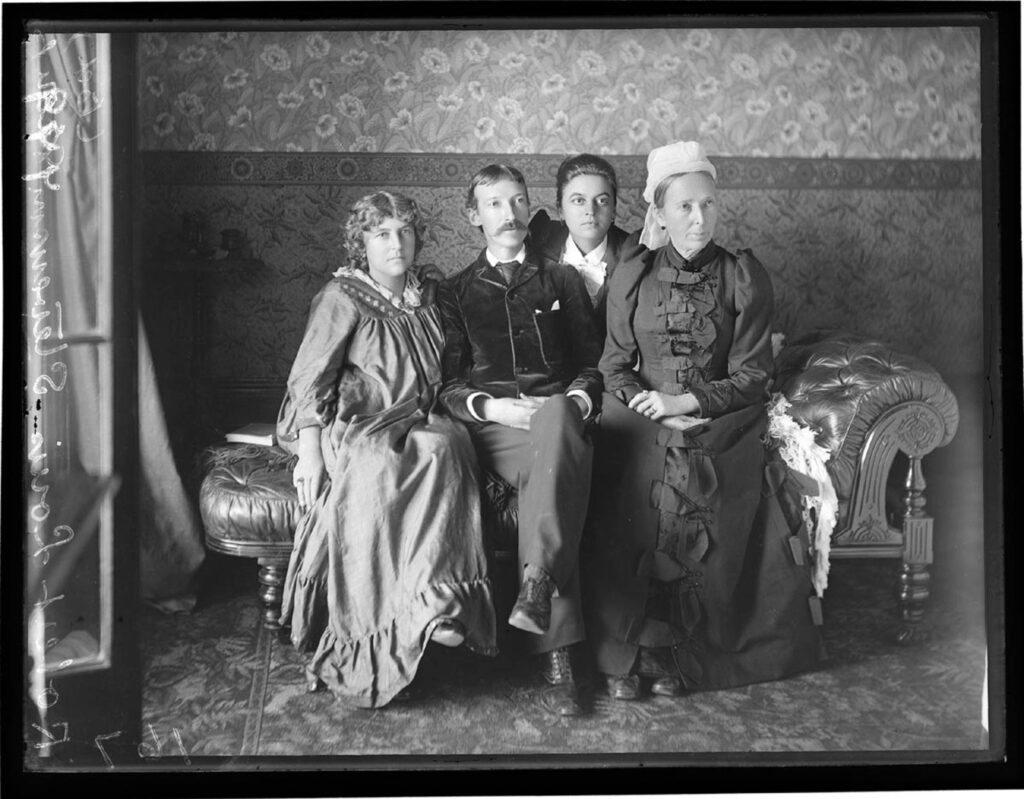

Fanny’s very presence in Stevenson’s life continued to be controversial. While Stevenson’s parents had come to accept her — his widowed mother lived with them in Samoa — his friends did not. They resented her for telling friends they couldn’t visit, and for inserting herself into his work. She long claimed that she was responsible for the success of Jekyll and Hyde, claiming that she’d insisted he completely rewrite the first draft of the work.

While there was no love lost between Fanny and Stevenson’s friends, there’s little doubt that they truly loved each other. But as the years at the estate in Samoa went on, Fanny continued to struggle more and more with a nervous illness that had plagued her for years. As for Stevenson, he did continue to write while living at the island estate, but he would never match the success of his earlier work. Most of his later publications were historical works or travel essays, and when they didn’t take off, he grew increasingly worried about money. That stress ratcheted up with the release of one of his histories that detailed the fight between colonial powers that were vying for control of the island; when the book was published, he began to worry that it was so controversial that he could be deported.

Stevenson’s stress and health issues finally hit critical mass on December 3, 1894. He worked on a fiction project in the morning and wrote some letters in the afternoon. Later, he helped Fanny make some mayonnaise. That’s what he was doing when he collapsed — he was dead by the evening, likely of a cerebral hemorrhage.

Robert Louis Stevenson was buried on the island, and his grave is marked by a stone on which is inscribed the epitaph he wrote for himself:

Under the wide and starry sky

Dig the grave and let me lie

Glad I did life and gladly die

And I laid me down with a will

This be the verse you grave for me

Here he lies where he longed to be

Home is the sailor home from the sea

And the hunter home from the hill

Fanny and her children only stayed on the estate for a few months after his death, although her ashes were buried beside him after her passing in 1914. When they were reunited, it was to a huge celebration in Samoa, as they were laid to rest in what has been called “the most inaccessible grave in English letters.”

It’s an appropriate description for the final resting place of the man who wrote the world’s most famous, beloved tale of pirates and buried treasure.