Even if you are not a lover of classical music, you may have felt that first rush of adrenaline at the top of the ‘Ride of the Valkyries’, or shed a tear or two at the first swell of ‘Here Comes the Bride’.

These are two among many of the famed compositions of today’s protagonists, one of the titans of music of all ages and genres, Richard Wagner.

A man who left a permanent mark not only on music, but on the philosophy, society, and politics of the 19th and 20th centuries. Today, we will explore his personal life, his main works, his controversial views. Finally , we will address the ultimate question of his legacy, which tied his music to the propaganda efforts of the 3rd Reich. But does he really deserve to be remembered as the soundtrack to an authoritarian, war-mongering regime?

I hope you are sitting comfortably, as today’s video is suitably Wagnerian in length.

First Notes of the Scale

Wilhelm Richard Wagner was born on May 22, 1813 in Leipzig, then part of Saxony, presently in modern-day Germany. This city is remembered for its contribution to arts, literature, and music. Composers like Johann Sebastian Bach, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and Felix Mendelssohn all worked as organists in the church of St. Thomas … the same church where young Richard was baptised! Not a bad start for a future giant of music.

Baby Richard would barely get to meet his father. Carl Friedrich Wagner, a police clerk, died in November of 1813 during a typhoid epidemic. A year later, Richard’s mother Johanna remarried, this time taking vows with noted actor, painter, and poet Ludwig Meyer. She moved in with him in Dresden, taking Richard and his eight siblings.

There is evidence that Johanna and Ludwig had been lovers for a long time, and that the artist may have actually been Richard’s biological father. Whatever the truth, Geyer had a strong bond with Richard and encouraged him to develop his creative, artistic side.

Unfortunately, the boy soon lost his second father figure, too. Ludwig died suddenly on November 30, 1821. But the Wagners stayed in Dresden for several more years, during which time Richard started taking piano lessons. He gravitated more towards literature; in his early teens, he penned his first work, a five-act tragedy called ‘Leubald and Adelaide’.

It was only after a move back to Leipzig in 1827 that young Wagner started taking music more seriously. During the second Leipzig tour, he began taking lessons in harmony and counterpoint. He also started attending performances from his favourite genre: Opera.

Richard composed his first serious sonatas and string quartets in the late 1820s. Encouraged by his natural ability, mother Johanna convinced him to enroll at Leipzig University to study musical composition. The young composer flourished: his piano sonata in B flat major impressed one of his teachers so much that he agreed to give him extra lessons for free!

At this stage, Richard’s compositions were ‘small’ in scale, if our musically-inclined friends will allow me this term. What I mean is that he focused on writing string quartets or sonatas — compositions for a single instrument. But in the early 1830s, Wagner began composing orchestral symphonies and even incidental music for a play, ‘King Enzio’, marking his debut in writing for a theatrical production.

As he began collecting his first favourable reviews, Richard decided it was time to compose a work in his favourite genre, opera. His inaugural work was titled ‘Die Hochzeit’, or ‘The Wedding’, but it remained incomplete.

You’d be forgiven for thinking this was an early sign of writer’s – or composer’s – block, but Wagner quickly bounced back with new finished works. Between 1833 and 1836, he composed his first two complete operas.

The first one was titled ‘The Fairies.’ In contrast to common practice at the time, Wagner wrote both the music and the ‘libretto’, or the text. It told the story of the love between a fairy princess and a human, opposed by the fairy’s father, but unfortunately it was never performed during Wagner’s lifetime.

His second go was ‘The Ban on Love’, a comic opera based on William Shakespeare’s Measure for Measure. This time, Wagner’s work earned a stage production … which promptly flopped after one performance.

So, if you ever despair about finding success in life, remember this: even Wagner totally flunked his first three operas.

But even these disappointments provided a great opportunity for Wagner to test and develop his musical and philosophical ideas.

While writing ‘The Fairies’ and its floppy follow-up, Wagner had become friends with Heinrich Laube, a key figure of the “Young Germans” literary movement. Inspired by their ideals, Wagner started to reject the values of Romantic poetry and music that were typical of the early 19th Century. Instead, he began developing a new, personal vision imbued with pan-Germanism and progressive, liberal political thinking derived from the early ideals of the French Revolution. These were political and philosophical sentiments which Wagner shared with many more young European intellectuals, disappointed by the Restoration.

At the same time, Richard had started courting actress Christine Wilhelmine Planner, known as ‘Minna’. Together they moved to Magdeburg and started working with the Bethmann theatrical company. It was with this troupe that Wagner had conducted the première of his second completed opera, The Ban on Love, in March of 1836.

The total fiasco that ensued bankrupted Bethmann’s company and left Wagner with few professional prospects. Luckily, Minna was a Planner not only in name; she sorted out their next move, which was a relocation to Königsberg, now modern-day Kaliningrad on the Baltic Sea. Here, she took a new job at the city’s main theatre, and the two lovers married on the 24th of November.

The Flying Saxon

Very soon after the arrival of the Wagners, the Königsberg theatre found itself on a slippery slope toward bankruptcy. Richard was also plagued by other troubles: Minna, not exactly the faithful sort of wife, had eloped with a young lover. Help came swiftly from Heinrich Dorn, a conductor Richard knew from his Leipzig days. Dorn secured a post as conductor for Wagner at the German Theatre in Riga, in modern-day Latvia. This job would give him financial security, and maybe even the chance to mend his relationship with Minna.

The plan worked. Well… sort of.

Wagner arrived in Riga in August of 1837, and by early 1838, Minna was again by his side. The two enjoyed a better quality of life for a short time, but more problems weren’t far behind. As the couple lived beyond their means, debts started to accumulate. At the same time, Minna had resumed her infidelities, accepting the courtship of the theatre’s very director. In other words: his wife had started dating his boss.

Wagner was also frustrated by the poor quality of the frivolous comedic operas he was forced to conduct.

Eventually, also this experience proved to be a disappointment. In 1839, the German Theatre did not renew his contract. With debt collectors literally pounding at his door, on July 10, Richard dragged Minna to the harbour and the two escaped on a smuggler’s ship amidst a formidable sea storm. Destination: Paris.

As the ship navigates the waves and winds, let’s ponder this man’s life so far. For a 26-year-old he had achieved some solid success, but also some catastrophic failure, professionally and personally. And yet, his luggage carried a wealth of experience he would later put to good use.

While in Riga, exasperated by the light nature of musical theatre, he had started writing the libretto for a new work: this would become the monumental opera ‘Rienzi.’ Based on a novel by Edward Bulwer-Litton, this is a historical piece about a 14th Century Roman leader and his populist uprising.

During his tenure at the German Theatre, Wagner also developed a new conducting stance, revolutionary in those times: rather than waving his baton while facing the audience, he faced the orchestra, to establish a closer connection with the musicians.

Finally, he took careful notes about the architecture of the German Theatre: he especially admired the dark auditorium, the simple décor, the amphitheatre layout, and the deep orchestra pit. These features would all later inspire the construction of his own theatre.

But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. The Wagners landed in France in September of 1839, after a tortuous journey during which Minna had suffered a miscarriage. A tragic event, which marked the beginning of another unfortunate period of marital conflict.

In Paris, Minna was able to ‘tread the boards’ now and again. Richard … well, the only wooden boards he saw were those of the doors slammed on his face. Apparently, Parisians had little interest in his music. Wagner took a day job completing arrangements for a music publisher, while he hustled to get ‘Rienzi’ on stage. An old friend from Leipzig, composer Giacomo Meyerbeer, interceded on Wagner’s behalf with the director of the Paris Opéra. Unfortunately, the Parisian establishment was too conservative to accept the work of a young, unknown, German composer.

Undeterred, Wagner continued to write and compose, completing his next opera: ‘The Flying Dutchman.’ This opera was inspired in part by a legendary ghost ship, as well as the Wagners’ own perilous voyage from Riga. Musically, it introduced for the first time one of Wagner’s signature techniques: the leit-motif, a recurring musical theme associated with a specific character or situation. The leit-motif concept has had a major lasting effect on modern and contemporary music — even on film or TV soundtracks. Consider the Imperial March from Star Wars, or the Rains of Castamere from Games of Thrones — two ominous accompaniments that sonically acknowledge the presence of series villains.

Back to the 1800s. While Wagner was composing The Flying Dutchman, he had the idea to hustle back home. He sent a petition to the King of Saxony, Frederick Augustus II, asking him to accept ‘Rienzi’ as a production at the Dresden Court Theatre. In June of 1841, the King accepted.

More than a year later, on July the 7th 1842, Richard and Minna left Paris to prepare the première of ‘Rienzi’. Considering Wagner’s track record, his relative obscurity, and the fact that the opera was five hours long… you can guess how it went, right?

Wrong. The opera debuted on October 20th, 1842, and audiences loved it!

The year 1843 took off with another rapturous debut — that of ‘The Flying Dutchman’ — a piece in which the composer further pushed the boundaries of operatic convention. These successes granted Wagner a new role as musical director of the Royal Court in Dresden. With newfound financial stability, the young composer could finally repay his many debts! Well, kind of. He actually borrowed more money to repay them! But who are we to judge? Are you running a credit check on him or something? Give the man some slack.

Besides, he had other concerns to keep him occupied.

This was Europe in the mid-1840s, and another age of political and philosophical debate was brewing after the post-Napoleonic restoration. A fuse had been lit under the continent, and a spark was gradually burning its way towards 1848, that bomb of a revolutionary year. The detonation was inevitable, and the young, restless Wagner had already picked his side.

While working for the King of Saxony, Wagner continued honing his operatic craft: the next of his operas to premiere was the ‘Tannhäuser’, in October of 1845. This work deals with the titular wandering Minstrel, torn between pagan beliefs and Christianity, between the pleasures of worldly passion and spiritual love.

While developing the libretto for this opera, Wagner began studying the mythology of German and Nordic lore, which he found to be a gold mine of inspiration. His favourite writer became medieval poet Wolfram von Eschenbach, whose works he used as a basis for two future operas, ‘Parsifal’ and ‘Lohengrin’.

‘Lohengrin’ revolves around a mysterious knight, who protects young Elsa against a malicious ruler, Count Telramund. Wagner completed it in April of 1848, just when revolutionaries across Europe were rising up against their own malicious rulers.

Wagner frequented the Dresden court while writing these new operas, but he preferred to mingle with revolutionary activists, who shared his progressive ideals, his desire for a constitutional government, or even his yearning for a united Germany. Most notable amongst them were August Röckel, the editor of the radical newspaper ‘Volksblätter’, and Mikhail Bakunin, the founder of collectivist anarchism.

Initially, Saxony was not involved in the revolutionary wildfire of 1848. But after more than a year of quiet dissent, in May of 1849, Dresden revolted against its King.

Revolution and Exile

The Saxon people took to the streets, pressing the King to institute social and electoral reforms. Wagner was on their side; he wrote articles against the aristocracy and in favour of a republican constitution, and he personally distributed revolutionary manifestos to the Saxon troops. Eventually, he got involved with some of the more serious action — on the May 7, 1849, Richard Wagner had volunteered to spy on troop movements, from the top of a church tower in Dresden. Soon, he spotted incoming troops! The problem was that they spotted him, too, and opened fire.

Luckily for the future of music history, those unnamed soldiers were bad shots, and Wagner escaped in one piece. But his name had already been compromised by his rebellious articles. When the uprising eventually failed, Saxon authorities issued an arrest warrant on May 16.

But the composer was on a streak of good luck. The warrant bore a very vague description of Wagner: “37 to 38 years old, of medium height, with brown hair and eyeglasses”

They might as well have written

“A guy, somewhere in Europe.”

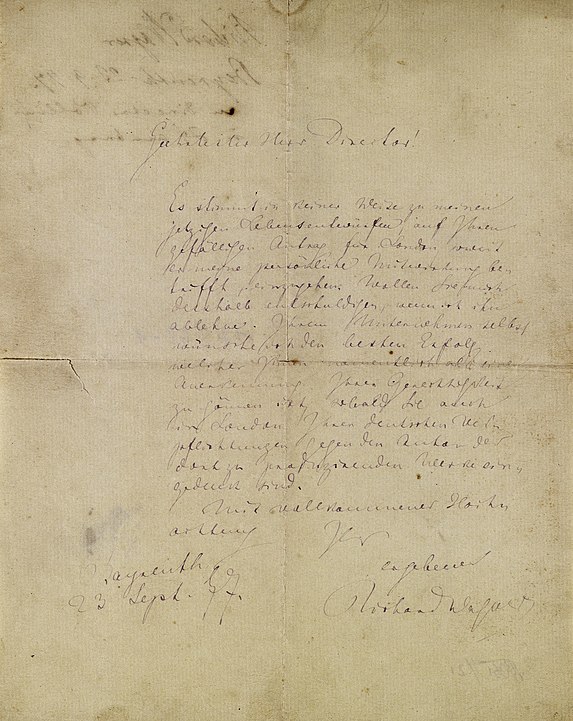

The incompetence of Saxon police allowed Wagner to escape Dresden and relocate to Zurich, Switzerland, with the help of his friend, composer Franz Liszt.

Wagner spent the next twelve years in exile from Germany, running low on morale, and even lower on funds. A group of friends thankfully arranged for him to receive a regular pension to give him some stability … except he sabotaged himself by having an affair with the wife of one of said friends.

Gratitude, eh?!

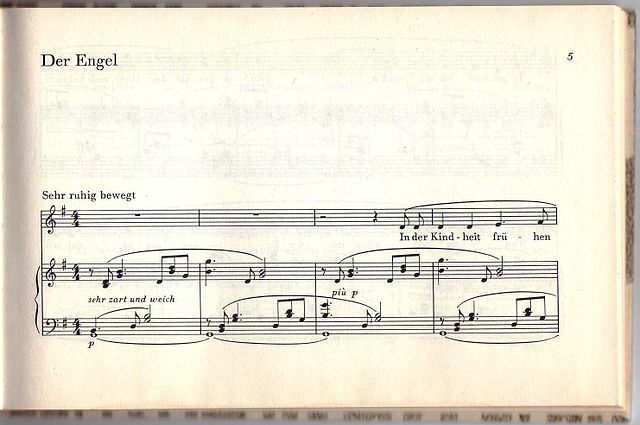

During the first years in Switzerland, the Wagners were again unhappy. Minna slipped into depression, while Richard suffered from composer’s block, if that’s a thing. He did write some essays, though. The first one, “The Artwork of the Future”, was a visionary work in which he described opera as a ‘total work of art’ which combined music, song, dance, poetry, visual arts and stagecraft.

The follow-up, published in 1850, was his infamous “Judaism in Music” essay. In this work, he expressed publicly for the first time his antisemitic views, which he held in private throughout his life, even extending his racial disdain ofr other nations.

His thesis was that Jews had no connection to the lofty German national spirit, and as such, were capable of producing only shallow and artificial music. According to Wagner, Jewish composers were only seeking popularity and financial success, incapable of conceiving genuine art. The Jewish artist could only

‘speak in imitation of others, make art in imitation of others, he cannot really speak, write, or create art on his own’.

It can be argued that Wagner did have many Jewish friends, and that anti-semitic views were quite common in Europe at the time. However, taking the time to write, edit, and publish such views really took the arbitrary hatred of a whole portion of mankind to another level.

And yet, Wagner’s musical genius cannot be denied, nor his drive for innovation of the musical medium.

While he was working on his first pamphlets, the composer had also started working on his best-known masterpiece, the four-opera cycle ‘The Ring of the Nibelung’, or simply ‘The Ring’.

This cycle includes ‘The Rhinegold’, ‘The Valkyrie’, ‘Siegfried’ and ‘Twilight of the Gods’.

The plot is inspired by Nordic mythology and revolves around a magic ring that can bestow the power to rule the world. The god Wotan steals the ring from his maker, the Nibelung dwarf Alberich, and then hands it over to giants Fafner and Fasolt, as payment for them building Valhalla.

Wotan’s mortal grandson, the hero Siegfried, slays Fafner to retrieve the ring, only to be killed by Alberich’s son. The Valkyrie Brünnhilde – Siegfried’s lover – returns the ring to the Rhine maidens, rightful owners of the gold from which the ring had been forged. She then commits suicide on Siegfried’s funeral pyre, before the gods and Valhalla are all destroyed in the Twilight of the gods.

If you want more details on the story, you are welcome to attend the full, 15-hour performance.

According to Karol Berger, professor of music at Stanford University, the Ring is an allegory for Wagner’s political beliefs, inspired by his revolutionary experience. Siegfried’s quest represents a struggle to wrestle power from the hands of capitalists – that’s the goldsmithing dwarfs – as well as the aristocracy – the gods.

In his lifetime, though, Wagner did not expound on the meaning of the cycle, but rather on his musical vision. In an 1851 publication, ‘A Communication to My Friends’, Wagner described his work as dramas, rather than operas. They would be performed at a specially designed Festival, over the course of four consecutive days, allowing audiences to enjoy the cycle in its entirety.

The composition of the Ring cycle absorbed most of Wagner’s energies during much of the 1850s

By June of 1857, the composer had written and composed the first two dramas and the first two acts of ‘Siegfried’, before setting them aside for another project, ‘Tristan und Isolde’.

Your Number One Fan

The plot of Tristan und Isolde borrows from the legends of King Arthur and is inspired by the philosophy of another Arthur: Schopenhauer.

Wagner had first read Schopenhauer’s works in 1854 and had become an easy convert to his philosophy: a deeply pessimistic view of the human condition, subject to the whims of blind, impulsive will. This is reflected in the story of the two titular characters — their love story is subject to irrational, destructive passion, which can only end in death. Schopenhauer’s ideas also influenced the balance of drama versus music.

Wagner had earlier theorised that the plot, dialogue and poetic aspect of an opera should be pre-eminent, with music in a subservient role. Schopenauer suggested instead that music was now the leading, passionate, almost irrational force whose tenor and tone drove the message to the audience.

Another source of inspiration for ‘Tristan und Isolde’ came from Wagner’s own infatuation with a married lady, poet Mathilde Wesendock. Again, this lady was the wife of one of Wagner’s patrons and benefactors. It must have been a heartfelt affair, but again, what I am learning is this: never lend money to Richard Wagner, for he will know how to repay you.

The affair collapsed in 1858, when Minna intercepted a letter to Mathilde from Richard. From then on, the couple was virtually separated. Minna returned to Germany, while Richard spent time in Venice, from where he continued his correspondence with Mathilde.

Minna and Richard tried to reconcile some years later, in Paris. Wagner had moved there again to organise a new production of ‘Tannhauser’ in 1861. This was a fiasco, as opponents of Emperor Napoleon III took the occasion to stage protests against his foreign policy beliefs. The reunion with Minna was similarly a debacle, and the two parted ways once more.

In the meanwhile, things were improving back home, in Dresden. Thanks to his friend Franz Liszt, productions of ‘Lohengrin’ and other works by Wagner had become all the rage in Saxony. His artistic success had pressured the Government to issue a full pardon for the revolutionary composer.

The King of Saxony waited with open arms, but Wagner had since set his sights on the patronage of another monarch: King Ludwig of Bavaria.

While still a 15-year old Prince, Ludwig had attended a performance of ‘Lohengrin’, a rapturous experience which left him in tears. Known to be eccentric, flamboyant, and even mad, Ludwig built a sort of private psychological fantasy around Wagner’s imaginary world, a retreat in which to escape from pressures of court life. This can be seen in the ‘fairy tale’ castles he had built, such as the astonishing Neuschwanstein or the whimsical Linderhof Palace – which came equipped with a golden swan-boat directly inspired by ‘Lohengrin.’

Naturally, when Ludwig was crowned King of Bavaria at the age of 18, one of his first acts was to summon Wagner to his court. By May of 1864, Richard had parted ways once and for all with Minna, although he still supported her financially, burying himself into more and more debt. Sensing an opportunity, he eagerly accepted the invitation.

At their meeting, the King enthusiastically offered to fund any opera the maestro wished to stage, and Wagner chose ‘Tristan und Isolde’. He had previously tried to produce it in Vienna, but the show never premiered, as it was deemed too difficult to perform and too expensive to stage.

But the King’s coffers were deep, so on June 10, 1865, the drama premiered in Munich.

The conductor for this run was Hans Von Bulow. Hans and his young wife Cosima had welcomed to the world their baby daughter, also named Isolde, just a couple of months earlier.

Well, not exactly ‘their’ daughter.

The biological father was – you guessed it – Mr Richard ‘Loose Pants’ Wagner.

Cosima was herself an illegitimate daughter of Franz Liszt, who disapproved of her affair with his friend Wagner. Another proof of my theorem: do Wagner a favour, he will do your wife. Or daughter. Or maybe both.

The affair, or rather the scandal, became the talk of Munich. At the same time, jealous courtiers were wary of the influence that Wagner had over the King and started pressuring Ludwig to get rid of him.

In December 1865, Ludwig was finally forced to ask the composer to leave Munich. The King even considered abdicating to follow his hero into exile, but Wagner convinced him to remain on the throne.

During his second Swiss exile, Wagner took time to revise and expand his pamphlet ‘Judaism in Music’, publishing the new version in 1869. This time, it received wider circulation and reaction than the previous edition, even causing mass protests at the performances of his new work, ‘The Master-Singers of Nuremberg’.

In the meantime, he had been ‘living in sin’ with Cosima, siring two children, Eva and Siegfried. The two eventually married in August of 1870, after Minna had died of a heart attack, and Cosima had obtained a divorce.

During the early 1870s, Richard and Cosima developed a friendship with a young and brilliant philosopher, one who had become Professor of Classical Philology at the age of 24. His name was Friedrich Nietzsche, a name forever associated with that of the composer.

A competent amateur pianist, Nietzsche had admired Wagner’s music and ideals since his student days. While teaching at the University of Basel, Nietzsche had taken the habit of frequently visiting the Wagners, who lived in nearby Luzern. The young philosopher became a staunch admirer of the older composer, which he considered a father figure. He also had potentially developed a small crush for Cosima, which may have justified the frequent visits.

In his 1872 book ‘The Birth of Tragedy’, Friedrich openly expressed his admiration for Wagner. In this work, he argued that Greek tragedy emerged from the dark and irrational spirit of music, partially tamed by principles of order. Over time, these elements had become imbalanced, with a preponderance of rationalism over the sheer creative impulse of music.

Nietzsche believed that this victory of Socratic rationalism was plaguing contemporary art, but that Richard Wagner could restore the old balance, with his impulsive and passionate music.

Having suffered through exiles and revolutions, Wagner now had a settled, stable domestic life, with a faithful wife and a devoted younger friend, a rising star in academia. He could now direct his energies towards completing his masterplan: the ‘Ring’ cycle.

A Cathedral of Music

The monumental Ring cycle needed a properly monumental opera house and Wagner identified the right theatre. This was the Margravial Opera House in Bayreuth, upper Franconia, by now part of the unified 2nd German Reich.

Wagner hated the décor of the place, finding it too lavish and intricate to his taste, but he loved the massive, 27-meter stage.

As the composer was finishing his work on the librettos and the scores, he began to rethink his decision on the venue for his magnum opus. Rather than compromising with the Margravial theatre, he would build a whole new venue that could provide every detail that he wanted. The design borrowed many ideas from the German Theatre in Riga, where he had worked as a young conductor. The main feature would be the orchestra pit, deep enough to hide the musicians from view, allowing audiences to focus entirely on the performance. This setup would allow for music to filter from under the stage, fill the wooden structure of the theatre, and surround the public with sound.

Such a project required massive funds, which Wagner raised by touring tirelessly … and by borrowing more money from his old friend, Ludwig of Bavaria.

The new theatre, the ‘Festspielhaus’ was completed in time for the premiere of The Ring of the Nibelungs, from August 13th through 17th, 1876.

The rehearsals were not a piece of cake.

The score was hellishly difficult, unlike anything else the tenors and sopranos had experienced so far. Wagner himself did not make things easier, micro-managing every aspect of the production.

Despite his best efforts, some serious cock-ups did take place, though.

A scene in ‘Siegfried’ required the presence of a massive, animated dragon. The beast was crafted in London and shipped in pieces to Bayreuth, but the neck – the most important component – ended up in Beirut.

But the show did go on!

The audience of the premiere included Ludwig of Bavaria, Kaiser Wilhelm and Emperor Dom Pedro II of Brazil. The south American monarch checked in at a local hotel, signing himself in simply as ‘Pedro’, occupation: Emperor.

What a boss.

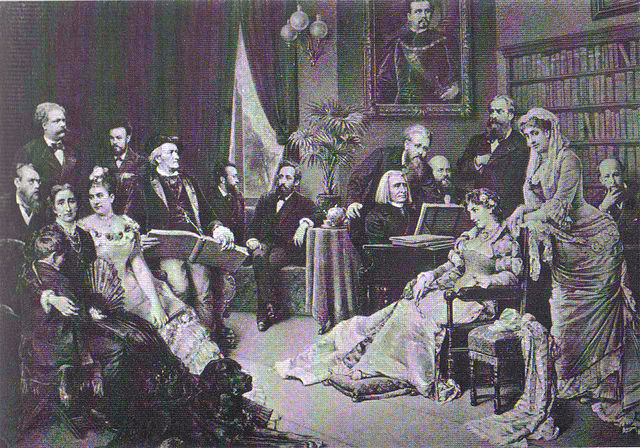

Another sort of royalty – intellectual royalty – attended in droves: Piotr Tchaikovsky, Franz Liszt, Leon Tolstoy, and Friedrich Nietzsche all had a seat at the Festspielhaus.

By this time, the relationship between the composer and the devoted philosopher had considerably cooled.

Ideologically speaking, Nietzsche did not approve of Wagner’s persistent antisemitism, nor his latest pet hatred: a dislike for French culture.

At the same time, Friedrich had come to re-evaluate his early disdain of rationalism, gravitating towards the materialistic and scientific ideas of his new friend Paul Rée – who happened to be French. And Jewish.

On a personal level, Nietzsche had become weary of Wagner’s overbearing egoism and disregard for the feelings of those around him. Case in point: at the premiere of the Ring, Wagner had his 24-year-old mistress Judith Gautier sitting next to him – in full view of poor Cosima!

Nietzsche’s 1876 paper, ‘Richard Wagner at Bayreuth,’ was critical of the composer, as an individual. However, the philosopher continued to recognize the merits of Wagner’s work.

It wasn’t just Nietzsche who was piling on the praise. The Ring was met with wild applause, lauded by audience and critics alike. Many praised the structural innovations employed by Wagner in his theatre, too; for example, he had asked for the auditorium to be left in the dark during performances. This is commonplace now, but back then, it was a revolutionary decision. Lights were always left on during shows, to allow for spectators to mingle or get a refreshment.

Wagner’s innovation instead demanded that audiences stay put and absorb a continuous flow of musical drama without interruption. This was another Wagnerian innovation: before him, operas were structured as a series of arias, duets, or other set-pieces, connected by ‘recitativo’ sections of very sparsely scored dialogue. The Master’s operas were conceived instead as a single, massive, continuing composition.

After the triumph of the Bayreuth Festival, Wagner began work on his last opera, ‘Parsifal’, which took him four years to complete. This was a mystical, near-religious experience to him, reflected in the abundant Christian imagery present in this drama. Eventually, he saw the performance of ‘Parsifal’ as a sort of sacred rite, which could be performed only in its own dedicated cathedral: the theatre at Bayreuth.

Wagner finished the score in January of 1882, and ‘Parsifal’ was performed sixteen times during July and August of that year, becoming known as the Second Bayreuth Festival.

The conductor for the whole run, Herr Herman, was the best Germany could offer, and he knew the score inside out. Wagner only had a minor niggle with him… his surname was Levi, and he was Jewish. Apparently the brilliant – albeit bigoted – composer could not stand the idea of a non-Christian musician being associated with his sacred work. Wagner pestered Levi for months, trying to get him baptised.

We can only imagine where Levi suggested Wagner could hide his baton.

Eventually, Wagner accepted that this Jewish musician would do an outstanding job after all, and the Parsifal was an incredible success.

Elated, but exhausted by the whole experience, Wagner and Cosima retreated to Venice. The couple, despite being generally happy, had been experiencing some tensions lately, and needed some time to themselves. The source of those tensions came from Richard himself, going through a full-on mid-life crisis. Cosima had recently found out that after Judith, he had been having an affair with young English soprano Carrie Pringle.

It seems that once Richard popped, he couldn’t stop!

Proximity to young lovers did not make Richard younger, nor healthier. Already struggling with a heart condition, at 2pm on February 13, 1883, Richard Wagner let out a cry of pain, while resting in his Venetian villa.

He died within the hour, as Cosima played the piano for him. A funerary gondola carried the maestro for a procession over the Grand Canal. His body was buried in Bayreuth, not far from his Cathedral of Music.

An Uncomfortable Legacy

In modern times, Richard Wagner’s legacy is frequently associated, even at superficial level, with the 3rd Reich and Nazi politics. It is easy to trace a straight line connecting Wagner’s antisemitism, Franco-phobia, German nationalism, Mysticism, and monumental, enthralling music, with the ideology and propaganda of Hitler’s regime.

But is this association really inevitable?

For sure, Adolf Hitler loved Wagner’s operas. In ‘Mein Kampf’, he even quotes ‘Lohengrin’ and how much it impressed him.

Hitler became Chancellor of Germany almost exactly 50 years after Wagner’s death. He took the occasion to organise lavish commemorations at Bayreuth and to forge friendships with Wagner’s descendants. In later years, and with the support of propaganda minister Josef Goebbels, Hitler and the Nazi party effectively appropriated some Wagnerian music and iconography for their propaganda efforts.

But this does not mean that Richard Wagner and the Nazi Party were exactly on the same wavelength.

One of the Party’s favourites was the ring cycle, and its protagonist Siegfried was interpreted as a fine specimen of Germanic fighting manhood. But as we have heard, Wagner’s idea was for Siegfried to be more of a subverter of established order, fighting against powerful elites.

It should also be said that a minister Goebbels liked to ‘pick and choose’ which of Wagner’s works suited his goals. For example, he decided to ban ‘Parsifal’ in 1939 because it promoted pacifism, spirituality, and brotherly love among men.

Not the best message, if you want to motivate your troops to invade Poland.

So, my humble opinion on the matter is that despite his controversial traits and philosophical beliefs, Wagner’s worldview was essentially at odds with bellicose and expansionist ideologies. But as usual, feel free to disagree in the comments and let us know what classical composer should we cover next.

SOURCES

Musical style

https://eno.org/composers/richard-wagner/

https://danielbarenboim.com/wagner-and-ideology/

Ideology

http://holocaustmusic.ort.org/politics-and-propaganda/third-reich/wagner-richard/

Biographies

http://www.wagneroperas.com/indexwagnerbioportal.html

Relationship with Nietzsche

https://www.thoughtco.com/why-did-nietzsche-break-with-wagner-2670457

Uncomfortable legacy

http://www.wagneroperas.com/indexwagnerbayreuthreich.html

https://www.theguardian.com/music/musicblog/2013/may/08/a-z-wagner-h-hitler