“He was a bad son, a bad husband, and a bad king, but a gallant and splendid soldier.” That was the description that historian Sir Steven Runciman thought best fitted Richard I. This was in line with the criticism brought against Richard by Victorian scholar William Stubbs who considered him a “mere warrior” who had no care for his kingdom or sympathy for its people.

Indeed, Richard I was an absentee ruler, spending only a combined six months out of his ten-year reign in England. The rest of the time, the king was either involved in wars or in captivity or simply preferring to reside in his French territories such as Anjou and Aquitaine. Today, scholars debate whether the king even knew how to speak English or not as he preferred his mother’s language of Occitan.

And yet, English history remembers him quite fondly. He was, after all, Richard the Lionheart, but was he truly deserving of this moniker? We will let you decide that for yourself as we explore the life of King Richard I.

Early Years

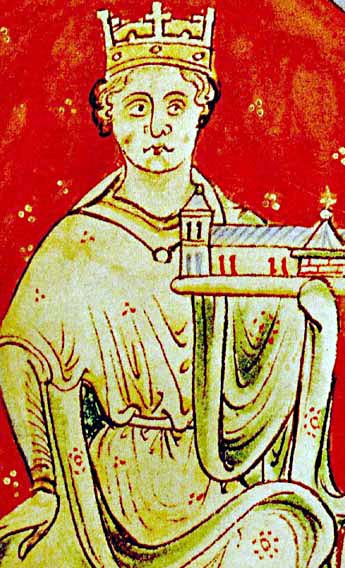

Richard was born on September 8, 1157, in Oxford, England. He was the son of Henry II, King of England, and Eleanor of Aquitaine, a very powerful and influential woman in her own right who prior to her marriage to Henry also served as Queen of the Franks as she had been the wife of King Louis VII before their marriage was annulled.

Richard was part of the House of Plantagenet, a royal dynasty that ruled over England for approximately 330 years. His grandfather, in fact, Geoffrey V, Count of Anjou, was the one who founded the house, while his father became the first Plantagenet to claim the English throne.

It was generally not expected that Richard would become king as he was the third son of Henry and Eleanor. The eldest son, William, died young before Richard was even born. His other older sibling, though, Henry, was the one ordained to follow in his father’s footsteps. In fact, in 1170, the family made an unusual move for English royalty and crowned the 15-year-old Henry as titular King of England while his father was still alive. He became known as Henry the Young King to help distinguish him.

This coronation was in name only and the elder Henry still retained authority. This became a bone of contention between father and son as the Young Henry grew frustrated with his father giving away possessions he considered to be rightfully his. He was spurred on by other noblemen, both English and foreign, who wanted to get rid of the elder king, and even his own mother who had a falling out with her husband.

This led to the Revolt of 1173-1174. Young King Henry had powerful allies including the aforementioned King Louis VII and William the Lion, King of Scots. He almost managed to secure victory but, in the end, Henry II was triumphant.

What role did Richard play in all of this? By the time of the uprising, he had already been made Duke of Aquitaine, a region of modern France that, back then, was a duchy that became an English possession when Eleanor married Henry. It was also the place where Richard spent a lot of his time both as a child and as an adult and which, by all accounts, he seemed to cherish far more than the whole of England.

Richard actually sided with his sibling during the revolt, as did their younger brother, Geoffrey. Of course, he was still a young man at that point and was clearly being influenced by other people, most likely his mother and King Louis of France. In fact, after the rebellion had been put down, Henry II imprisoned Eleanor of Aquitaine to keep the boys in line and to minimize her influence on them. She would stay under lock and key for the next 16 years.

Richard the Duke

As for his rebellious sons, Henry was merciful and forgave them after they submitted to him. Richard retained the title of Duke of Aquitaine and his father tasked him with the punishment of the nobles who rebelled against the English king. Henry’s orders were for most castles in the duchy to be reduced to the state they were 15 days before the start of the uprising, but he specified that some of them should be completely razed to the ground. Obviously, this did not sit well with some of the local noblemen who refused to stand down and continued their rebellion against Richard.

Henry placed a lot of trust in his 18-year-old son and his military prowess as he gave Richard full command over the duchy’s armies, as well as control over local revenues. Perhaps he was impressed with how Richard handled himself during the revolt, even if it was against him. Certainly, Richard would develop a reputation as a great fighter and military leader, as opposed to his older brother Henry who was described as giving “no evidence of political sagacity, military skill, or even ordinary intelligence.”

Richard spent the next few years as his father’s regent in Aquitaine, putting down rebellions. We have knowledge of his efforts courtesy of 12th-century chronicler Roger of Hoveden. The young duke made special mention of his successful siege of Castillon-sur-Agen. It was heavily fortified and required the use of artillery but, after two months, Richard managed to break the garrison. Clearly, he was quite pleased with himself as it was, arguably, his first impressive military triumph. These successes started establishing his reputation as an adept commander, but also his penchant for cruelty as he showed little mercy to those who stood in his way.

Some nobles proved to be bigger challenges than others. The Rancon family, for instance, were a major thorn in Richard’s side. They were lords in Taillebourg, led by Geoffrey de Rancon, and their castle was considered impregnable. Built on a rocky outcrop on the right bank of the Charente River, it was unassailable from three sides while the fourth was heavily fortified.

Richard’s strategy was to make himself an irresistible target so that his enemies would leave the fortress and come to him. He destroyed the village that was nestled beneath the citadel. He began burning down the surrounding fields. He even placed his camp close enough to the castle walls so that Rancon would consider a surprise attack. Meanwhile, he deployed artillery to make it look like a standard siege and then waited. Sure enough, his enemies launched a counterattack, but were defeated by the duke’s army. Richard’s men were then able to force their way into the castle and, after three days of looting and destruction, Rancon surrendered. This was truly a notable victory so much so that, upon hearing of it, other rebellious noblemen decided that the fight was not worth it and also laid down their arms in front of the Duke of Aquitaine.

Rise to the Throne

Peace throughout the land did not last long. Many historians of that time all said that Richard was a cruel man who “oppressed his subjects with unjustified demands and a regime of violence.” All the nobles hated him so they banded together to try and drive him away from the region and even sought the help of Philip II of France.

Eventually, King Henry had to intervene and he ordered Henry the Younger to come along, as well. He listened to the local noblemen. Again, Roger of Hoveden gave the most detailed account, saying that the barons complained that Richard took their wives and daughters by force to satiate his own lust and that when he was done with them, he gave them to his soldiers. We don’t know if such accusations were true, but it didn’t matter because Henry saw nothing wrong with them. Like father, like son, I suppose. He subdued the rebellion in 1182 and returned to England.

The nobles saw another opportunity, though. While Richard and King Henry could not be reasoned with, perhaps they could appeal to Henry the Younger. Almost a decade after his failed revolt had passed and he still had no lands to claim as his own while Geoffrey had Brittany and Richard had Aquitaine. Of course, in time, when his father died, he would have claimed the whole of England, but Henry was impatient. When the French barons promised they would recognize him as the new duke, the idea of invading Aquitaine was firmly implanted in his head. All he needed was an excuse that would appease his father.

That excuse came in the form of a castle that sat on the border between the lands of Richard and King Henry, a castle that Richard had spent time repairing and reinforcing. Young Henry wanted it and the king ordered the Duke of Aquitaine to give it to his brother as homage. Richard refused and his brother invaded his land with help from many Aquitaine nobles. Younger brother Geoffrey also joined the invasion against Richard.

Although at first he tried to remain neutral, the elder King Henry eventually sided with Richard. Even so, the war was not going in their favor. Henry the Young King was poised to win, but he fell ill suddenly and, on June 11, 1183, he died of dysentery, marking the end of the rebellion. Richard was now heir to the throne.

His other brother Geoffrey also died in 1186, allegedly by being trampled during a jousting tournament. There was only one other brother remaining – the youngest of all, John, who, so far, had not taken part in any of his family’s political and military machinations.

Contemporary chroniclers claimed that John was his father’s favorite. Not very hard to imagine seeing as how he was the only legitimate son of King Henry who didn’t raise his sword against him. Because Richard was now poised to rule over England and other territories such as Anjou and Normandy, King Henry wanted him to give the duchy of Aquitaine to John. Richard refused as Aquitaine was the territory he cared about most, perhaps even the only one he truly cared about.

For a while, it looked like it would be war again between the Plantagenets, but Henry had an ace up his sleeve. He finally released his wife, Eleanor of Aquitaine, from prison. She returned to her homeland where she still was the rightful ruler and Richard, who still had great affection for his mother, willingly surrendered all power.

However, he found a new ally in King Philip II of France, also known as Philip Augustus. There were tensions between Henry and Philip over a marriage that fell through and they escalated to violence. Richard officially paid homage to Philip and sided with him against his father. The duo were triumphant and, at the same time, the older Henry fell gravely ill. After he was defeated, Henry was forced to recognize Richard as sole heir. He died two days later, on July 6, 1189, and Richard became the new King of England.

Richard may have been the new king, but he had no time to concern himself with matters such as running his kingdom – he had a crusade to get to. Ever since 1187 when Sultan Saladin, founder of the Ayyubid Dynasty, had captured Jerusalem, the pope had been calling on the European powers to launch a new crusade and take back the Holy Land. And by the way, if you would like to study the topic in-depth and see it from the other perspective, we have already done a Biographics video on Saladin, you can check that out in the link below.

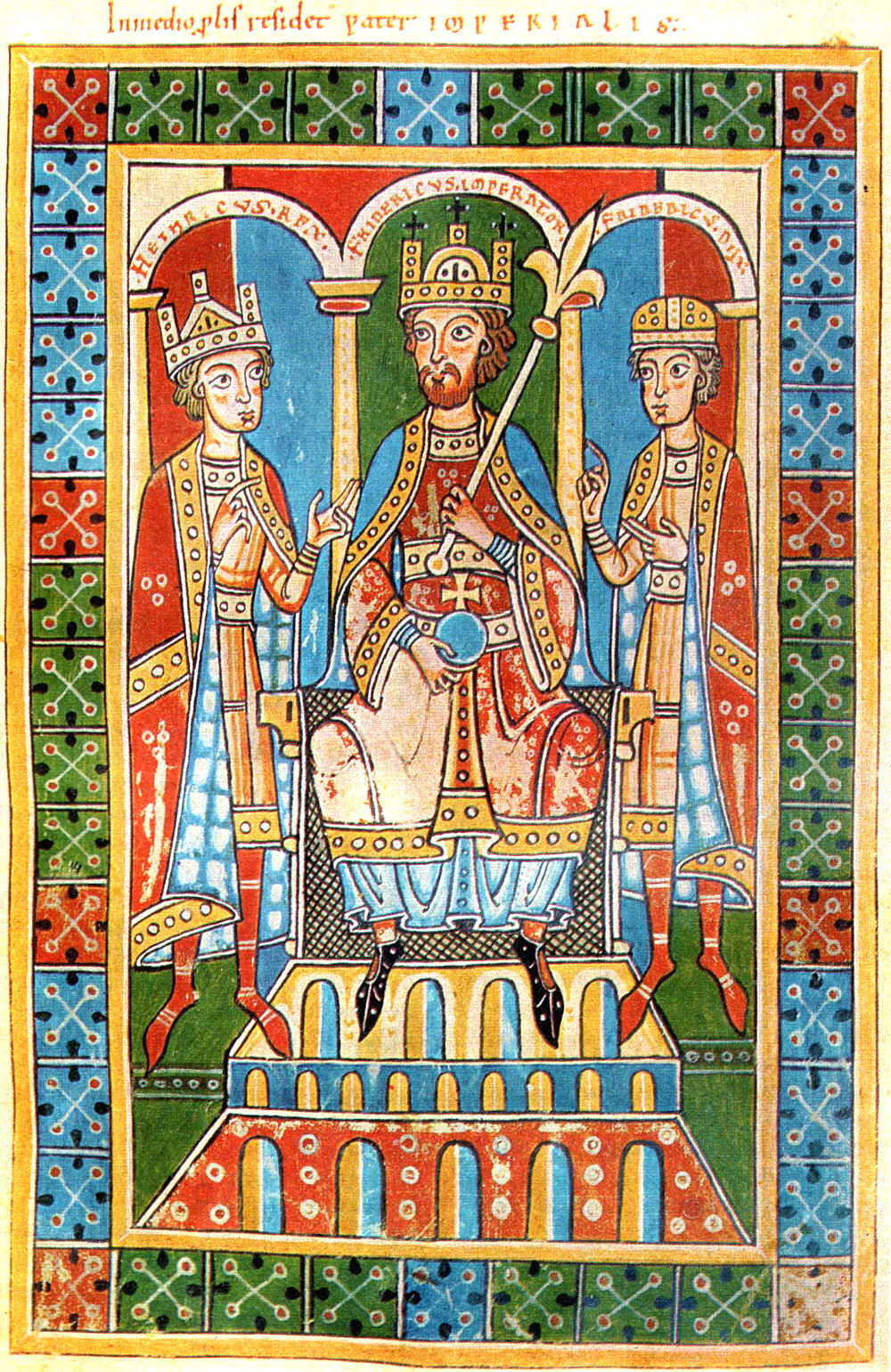

There were three major powers involved in the crusade: England and France, led by Richard and Philip, and the Holy Roman Empire, led by Frederick I or Frederick Barbarossa. There were, of course, vassals, such as the Hungarian forces led by Prince Géza and the Austrians led by Duke Leopold V.

King Henry II was actually the one who pledged his service to the crusade, or “taken the cross”, as it was called, but he wasn’t exactly enthusiastic about the cause. He was old, and frail, and had plenty of things back home to worry about, but public opinion eventually pressured him into joining.

There were actually preachers and minstrels back then who would walk into villages or town squares and rally the people to take the cross. They used propaganda pictures such as images of Christ being struck by an Arab soldier or of his tomb being trampled by a Saracen knight and his horse peeing on it.

Richard needed no such persuasion nor was he doing it out of obligation like his father. We cannot say how devout he truly was, but he was a soldier looking for a fight and, back then, there was no greater fight than taking down Saladin and recapturing Jerusalem. He did apparently have some kind of religious experience en route to the Holy Land and became overcome by a need to confess his sins and renounce his wickedness. He summoned all the bishops, stripped himself naked, kneeled in front of them and began flailing himself with whips.

Before all this, though, Richard needed money to raise and equip an army for his crusade. Prior to his death, his father enacted a new tax called the Aid of 1188, or better known as the Saladin tithe, as did Philip in France. King Richard also began selling official positions and other privileges, while also forcing those who already held such titles to pay a tidy sum in order to keep them. As you can imagine, this did not sit well with many of his countrymen, both rich and poor. Richard had little concern for them, though, as it was often said that he looked at England not as a kingdom, but as a source of money and soldiers. According to legend, when someone complained about the king’s new money-making schemes, he declared that he would sell London itself if he could find a buyer.

Marriage Troubles

Richard left for the crusade in the summer of 1190, accompanied by Philip Augustus who led the French army. His first stop was in Sicily where Richard sought to resolve an unrelated matter. The previous year, King William the Good of Sicily had died and his cousin Tancred became the new king. Tancred also imprisoned William’s widow and denied her inheritance. As it happened, that widow, Queen Joan of Sicily, was Richard’s sister. Unsurprisingly, the English king demanded that his sister would be released and given her inheritance. Tancred refused so Richard captured and plundered the capital of Messina.

Eventually, the two kings signed a treaty and this was mostly notable because it prompted Richard to assign an heir. It wasn’t his younger brother John, but Arthur of Brittany, the only son of his dead brother Geoffrey, who would have to marry one of King Tancred’s daughters.

Speaking of marriages, Richard himself needed a queen and, while he was in Sicily, his betrothed arrived. She was Berengaria, daughter of King Sancho the Wise of Navarre.

This caused problems with his French ally. You might recall we previously mentioned that King Philip of France and King Henry II of England had a falling out over a failed marriage. That marriage was supposed to be between Richard and Philip’s half-sister, Alys. It had been arranged while the two were children and Alys came to live at Henry’s court until she came of age. However, both Henry and Richard kept delaying the wedding. According to sordid rumors, Henry had taken Alys as a mistress and Richard knew this and did not want to marry her anymore. Philip and Richard managed to reach a settlement to finally break off the marriage, but the two left Sicily at different times.

Richard set off with his fleet across the Mediterranean in April 1191. However, he encountered a great storm that destroyed some of his ships. The vessel which carried his sister and his wife-to-be shipwrecked on Cyprus where they were taken prisoner by Isaac Komnenos, the tyrant who ruled over the island.

Richard successfully secured the release of Joan and Berengaria, but Komnenos refused to return the large treasure which had also been aboard the ship. Obviously, he was feeling confident in his position, but fate was against him. Richard invaded Cyprus and conquered it. Not only did he get his treasure back plus all the stuff he looted on top of it, but he later also sold Cyprus to Guy of Lusignan, the former King of Jerusalem.

While on Cyprus, Richard married Berengaria and the new queen returned to her native home. She became known as “the only English queen never to set foot in the country” because it was believed she never visited England, although it is possible she may have done it after Richard’s death. The two never had any children, although Richard did father an illegitimate child named Philip of Cognac whose mother remains a mystery.

The War for Jerusalem

After all the detours and distractions were finished, Richard finally arrived in the Holy Land in the summer of 1191. The port city of Acre was the first target of the crusaders and it fell pretty easily. In fact, Richard’s main problem during this crusade were not the enemies, but rather his allies.

He and Philip were already on the outs, not only over what had happened previously, but also because the French king wanted half of Cyprus. As Philip fell ill, he decided to return home after the fall of Acre.

Then there was the Holy Roman Empire and its vassals. The king, Frederick Barbarossa, had actually already died by this point in not quite the most dignified way, to be honest. He didn’t perish in glorious battle, but rather he drowned crossing the Saleph River in modern-day Turkey. Some sources say that the old king tried to brave the currents single-handedly, but others specify that he was thrown off his horse and he was too weak and his armor too heavy to get up again. Either way, his death caused many German soldiers to return home and left Duke Leopold of Austria in charge.

Leopold and Richard did not get along and the latter greatly insulted the former after the duke hanged his banner in triumph alongside the English and French ones after the battle at Acre. Richard felt that, as a vassal, Leopold was being arrogant, so he had the Austrian banner torn down. In reply, the Duke of Austria took his men and went home.

The crusade lasted for another year. Richard had other successes, particularly at the Battle of Arsuf where he scored a decisive victory despite being taken by surprise and being heavily outnumbered. This was, perhaps, Richard’s greatest triumph and it allowed him to retake the city of Jaffa.

Richard now had the upper hand against Saladin but, again, he was facing troubles from his own camp. Many of the men grew tired of the fight, and the French soldiers that Philip left behind simply refused to obey him any longer. Furthermore, disturbing reports from back home said that his brother John was making a play for the throne. To top it all off, Richard fell ill with scurvy. Perhaps for the first time in his life, the war-obsessed king acted practically. He concluded that he would not be able to keep Jerusalem, even if, by some miracle, he managed to capture it, so he opened peace talks. On September 2, 1192, Richard and Saladin signed the Treaty at Jaffa.

The Christian crusaders didn’t get much, but it was the best they could hope for under the circumstances. Obviously, their main objective of reclaiming Jerusalem had failed. But the treaty guaranteed a three-year truce between both sides, allowed the crusaders to keep Acre plus a small part of the coastline and promised safe passage for Christian pilgrims.

The Lion Slain by an Ant

Richard needed to return to England, but was wary of traveling through Philip’s territories as, by that point, the two were openly hostile to one another. He sailed on the Adriatic, but his ship washed ashore in Venice. While passing through Vienna, his retinue was discovered and captured by Duke Leopold who also had plenty of enmity for the English king. He turned him over to the new Holy Roman Emperor Henry VI who imprisoned Richard and asked for a humongous ransom for his release.

John, of course, had no interest in securing his brother’s release, but his mother Eleanor started immediately to raise the money. She did this, of course, by taxing everyone to the bone and confiscating treasures and property. After over a year in prison, Richard was released in 1194.

He returned to England where he was crowned again to further establish him as the king. In a rather strange move, Richard not only forgave his brother John for revolting, but also named him as his new heir. Perhaps Richard simply wanted to calm things down in England so he could refocus his attention. He was already ready to go on the warpath again, this time against France. During his incarceration, Philip had conquered Normandy and Richard wanted to get it back.

Image: Chateau Gaillard

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chateau_Gaillard.jpg

King Richard left England less than a month after his second coronation, never to return again. He reigned for another five years, but he spent all that time warring with Philip, only interrupted by the occasional truce. Richard’s crowning achievement at that time was the construction of Château Gaillard, a new castle that was considered a masterpiece ahead of its time.

Perhaps fitting for a man so obsessed with warfare, King Richard’s demise did not come against a mighty foe such as Saladin or Philip, but rather while fighting some French peasants. He was suppressing a minor revolt in the region called Limousin and had besieged a small, unassuming castle named Châlus-Chabrol. Richard was patrolling the perimeter and inspecting his men, paying little notice to the arrows occasionally fired at them from the castle walls, even mocking the archers at times.

Fate does not like to be tempted like that so, of course, a bolt from a crossbow hit the king in the shoulder, right below the neck. Richard was taken to his tent where he collapsed. The wound was poorly treated and developed gangrene.

According to the chronicles of Roger of Hoveden, the shooter was a boy named Bertrand whose father and brothers had been killed by Richard. The king allegedly showed mercy and ordered that the boy be set free and given 100 shillings. It is unclear if his order was followed, though, as some sources claim the king’s officers hanged Bertrand alongside everyone else in the castle. King Richard died two weeks later on April 6, 1199, by his mother’s side. As mentioned in his epitaph, “the lion was slain by the ant.”