To his friends, he was the Blond Beast. To his enemies, he was the Hangman, or the Butcher of Prague. To the man he devoted his life to, he was the Man with the Iron Heart. During his life, Reinhard Heydrich was known by many names, too numerous to list here. But you probably associate him with one name in particular: Heydrich was the Nazi target of Operation Anthropoid.

A talented classical musician who threw it all away to become a military man, Heydrich was the Nazi ideal made flesh. He was tall. Blond. Cultured. A lover of Wagner. He was also brutal. It was under Heydrich’s watch that the infamous Einsatzgruppen were formed, under his direction that Nazi enemies were killed, and to his designs that the Holocaust was perpetrated. Assassinated by the Czechoslovak resistance in Prague in 1942, Heydrich is a mystery: a sensitive, cultured boy who somehow grew up to be one of history’s worst monsters. Join us today as we journey into Prague’s heart of darkness.

A Young Lad of Promise

If you were shown the conditions Heydrich was born into and asked to guess what you thought he’d grow up to be, “genocidal maniac” would probably be far down your list.

Born Reinhard Eugen Tristan Heydrich on March 7, 1904, the world baby Reinhard came into was one of middle class luxury.

His father Bruno was an opera aficionado who ran a music conservatory in the German town of Halle, near Leipzig, while his mother, Elisabeth, was a pianist from a wealthy family.

For young Heydrich, that meant a life of culture, money, and – most importantly – music.

Music was the air the family breathed. Bruno wrote his own operas and sang on stage, while Elisabeth had little Heydrich trained to exacting classical standards on the violin and cello.

But there was a cloud hovering over the family’s charmed life, a cloud that only really counts as a cloud if you live surrounded by German nationalists.

Everyone in Halle thought Bruno was Jewish.

You may be thinking “um, so what?” But Bruno didn’t feel that way. He was certain his supposed Jewish background was why his opera career never really took off.

As time went on, he began to loathe the religion he blamed for his own failings. And he made sure young Heydrich loathed it too.

Still, this unpleasantness aside, their family life was relatively normal. Elisabeth was a strict mother, determined her son should succeed, and soon Heydrich was not just an accomplished musician, but a powerful sportsman too.

This normal family appearance only began to crack in 1914.

Like many Germans, the Heydrichs were at first excited by WWI’s outbreak, thinking it’d be an easy win for their country.

But, as first the weeks dragged on, then the months, and finally the years, that optimism began to fade.

In the winter of 1916-17, fuel and food shortages brought on by the war led to starvation and misery across the nation. In Halle, work at Bruno’s conservatory dried up as the economy faltered.

As 1917 rolled on, the German population grew angry at the war’s management. They began striking, protesting.

Before long, the cities were in turmoil, as running street battles erupted between far right nationalists and Communists.

Halle wasn’t spared. As a teen, Heydrich watched left and right extremists battle for control of his city’s streets.

Unlike his terrified parents, Heydrich found the clashes intoxicating.

In October, 1918, German dreams of winning the war finally collapsed with a resounding crash. Germany removed the Kaiser from power and brought in a civilian government tasked with negotiating peace.

In the aftermath, whole segments of the military went into rebellion. Before the war had even ended on November 11, the country was in revolution.

As a Communist uprising seized control of Berlin, Heydrich decided he had to make a stand.

In Halle, the now nearly 16 year old boy joined a local Freikorps unit. Intended as an anti-Communist militia, the Freikorps soon bloomed into a far right paramilitary force that targeted Jews and revolutionaries alike.

For the teenage Heydrich, the experience was an eye-opener.

For the first time in his life, he was surrounded by people who felt like he did. People who shared his anti-Semitic beliefs, his dislike of Communists. His desire to use violence.

By 11 August, the country was back under control. The Weimar Republic was founded, and Germany began to adjust to its new life as a democratic nation.

But the revolution of 1919 had unleashed the forces of far right nationalism. And Heydrich wasn’t the only one to heed their siren call.

A Sick Republic

The early days of the Weimar Republic were marked by a never-ending series of political wildfires.

On March 13, 1920, an ultranationalist putsch captured Berlin and held the city for a few days before the government regained control.

Three years later, another rightwing putsch, this time in Munich, killed 20 people. It’s leader? One Adolf Hitler.

You might be expecting to hear that Heydrich was in the thick of all this, cheering on the Nazis.

Well, you’d be wrong.

After the Freikorps disbanded, Heydrich had hung around in Halle just long enough to get his high school diploma, in 1922. He’d then high-tailed it out of his hometown as fast as he could.

But he hadn’t gone running to the Nazi party.

Heydrich had joined the German Navy.

By 1922, Weimar Germany was in the grip of hyperinflation. The economy was in ruins. Anyone who wanted a roof over their head and three square meals a day joined the military.

And Heydrich wanted more than that. Now a lad of 18, he was ambitious. He wanted to become an admiral.

He still flirted with the far right, maintaining membership of the anti-Semitic Deutscher Schutz und Truzbund. But while most future high-ranking Nazis were passionate true believers who were willing to forego a normal life for their cause, Heydrich wasn’t like that.

He wanted a respectable career with responsibility. When Hitler published Mein Kampf from his jail cell in 1925, Heydrich didn’t even bother to read it.

By 1928, Heydrich’s diligent good work had paid off enough for him to be promoted to first lieutenant and assigned to Navy Intelligence.

While he was still taunted for his supposed Jewish roots, the bullying he used to receive for his cultured side was long gone. Now a grown man, Heydrich’s sensitive qualities were no longer a burden.

In fact, they made him something of a catch.

Throughout the late 1920s and early 1930s, Heydrich sowed his wild oats like a man hoping to rival the Quakers in breakfast production.

It was during this seductive phase that Heydrich met Lina von Osten.

Aged just 19, Lina was everything Heydrich wanted in a woman. She was charming, intelligent, in awe of him.

And she was a fervent National Socialist.

By 1930, the Nazis were well known in Germany. But they weren’t yet in charge. When Heydrich first met Lina, he actually made fun of her for being a Nazi, calling the leadership clowns and deriding Goebbels as a “cripple”.

Little did the ambitious sailor know he was only a few short months away from joining those clowns.

In early 1931, Heydrich proposed to Lina. He then forwarded a copy of the engagement announcement to another girl he was seeing, as a way of breaking up with her.

But Heydrich’s classy methods soon returned to bite his Germanic arsch when the girl’s father found the announcement and hit the roof.

He actually complained to the Navy! And the Navy responded by actually firing Heydrich!

On April 30, 1931, Heydrich was discharged. When he got the news, the future Butcher of Prague locked himself in his room and cried like a baby for days on end.

When Heydrich finally emerged from his epic cry-a-thon, Lina was all like “dude, this is perfect. You can get a job with the Nazis!”

At first, Heydrich wasn’t enthusiastic. His main sticking point was that he didn’t think there were good enough career prospects.

But Lina kept pushing him and, eventually, he joined up, becoming member 544,916.

It was the beginning of a rise toward infamy.

Making a Monster

At this point, you might be wondering how Heydrich the lothario sailor became Heydrich the Nazi.

The answer is, surprisingly: his grandmother.

By the time Heydrich joined the Nazis, his mother and grandmother were already enthusiastic members. And they’d carried their wealth and connections into their new lives.

Within a month of Heydrich joining, his grandmother had arranged a private meeting between Heydrich and SS leader Heinrich Himmler.

It’s gotta be said, Himmler wasn’t all that happy. The only thing that convinced him to go was that Heydrich’s grandmother had inflated her grandkid’s connections to Naval intelligence, which might be useful to the Nazis.

When the two met in Munich, Himmler curtly gave Heydrich twenty minutes to outline a counterintelligence operation for the Nazi Party.

Twenty minutes later, the Blackshirts’ leader collected his jaw off the floor and offered Heydrich a job.

Heydrich had aced the interview. Despite only ever holding a low position in Naval Intelligence, he managed to use all his knowledge to outline an effective strategy.

When he hit a blank spot in his knowledge, he improvised, using the plots of half-remembered spy novels.

And it worked. Himmler recruited Heydrich into the SD – the SS intelligence branch – then and there.

It was the beginning of a partnership that would eventually leave Europe in ruins.

Although Himmler is infamous in his own right, he and Heydrich could be seen as a double act: the Laurel and Hardy of mass murder.

During the Night of the Long Knives, in 1934, Himmler and Heydrich worked together to exterminate the powerholders in the SA – the Nazi Brownshirts.

One of those killed was SA leader Ernst Rohm, godfather to Heydrich’s own child.

In the aftermath, Himmler awarded Heydrich by promoting him to Chief of the Gestapo. It was just the first in a sequence of events we’re gonna call “Himmler promoting Heydrich like crazy”.

In June, 1936, for example, Himmler merged the SD, the German criminal police, and the Gestapo into a single unit and gave it to Heydrich.

Three years later, in September, 1939, Himmler consolidated every single intelligence operation across the entire Third Reich under Heydrich. The new Reich Security Main Office (RSHA) was so powerful even other Nazis were kept in the dark about its existence.

Not that Heydrich didn’t earn his new position.

For a guy who once called the Nazis clowns, Heydrich had taken to his new job like a fascist duck to water.

In November, 1938, he’d directly organized the looting and burning of Jewish property known as Kristallnacht.

A year later, in August, 1939, Heydrich had also masterminded the false flag attack on Geliwitz that gave the Nazis a pretext for invading Poland.

In fact, many of the most infamous Nazi actions can be traced back to this one opera lover from Halle.

After the invasion of Poland in September 1939, for example, Heydrich was put in charge of the Einsatzgruppen.

The Einsatzgruppen were death squads that followed in the wake of invading German armies, mopping up enemies of the Reich.

Their brutality was legendary. In the first three months after the occupation of Poland, they murdered 50,000.

When the Nazis pushed east, in 1941, it was even worse. Over 33,000 Jews were killed in just two days in Kiev by Einsatzgruppen.

Not that Heydrich’s crimes only happened abroad.

In 1939, as Germany went to war, Heydrich had instructed his security service to focus on the Reich’s internal enemies.

In the dying days of that year, officers fanned out across German territory, liquidating gypsies, Freemasons, homosexuals, Jehovah’s Witnesses, intellectuals.

Taken together, it was a tsunami of bloodshed. A wave of annihilation unlike anything Europe had seen in generations.

And the worst was yet to come.

“The Eternal Subhuman”

On November 12, 1938, Reinhard Heydrich reported on the Jewish question to a gathering of Nazis.

Referring to Europe’s Jews as “the eternal subhuman”, he declared that imprisoning them wouldn’t be enough, and that the Reich would have to get rid of them.

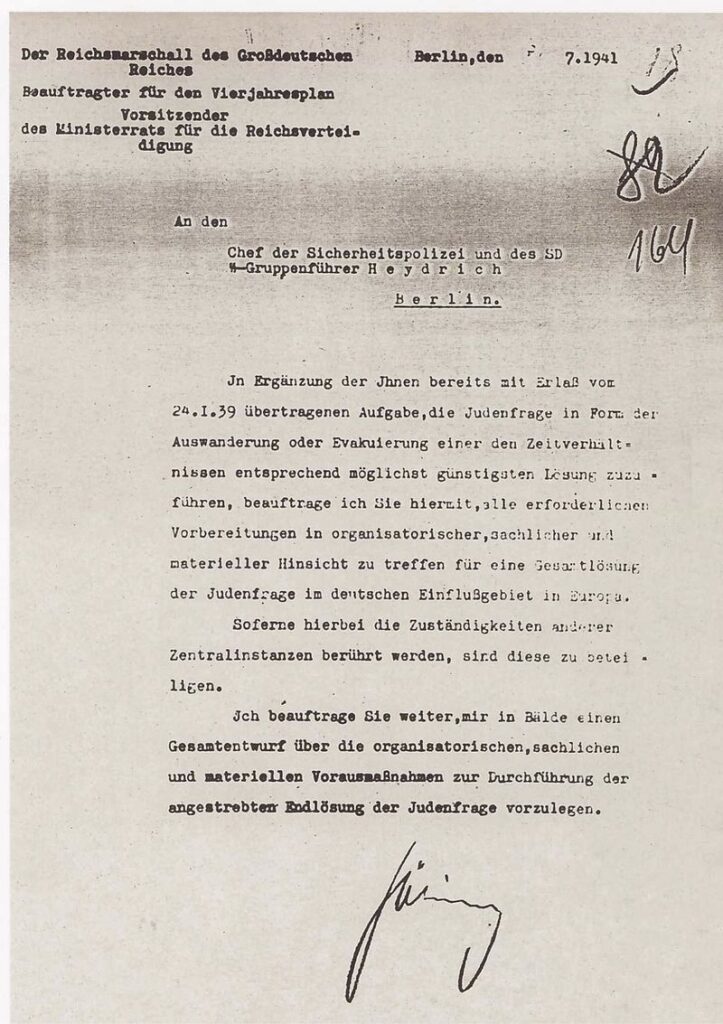

Not three months later, Hermann Goering took Heydrich to one side, and told him to “solve the Jewish problem”.

At this stage, what Goering meant was a policy of forced emigration and brutal tactics that would chase the Jews out of Germany.

But, even in early 1939, it was clear the Blond Beast wouldn’t stop at emigration.

It started after the invasion of Poland. As the Einsatzgruppen were unleashing Hell, Heydrich and Adolf Eichmann quietly worked together to have all of Austria’s Jews rounded up and deported.

Later that year, Heydrich directed the opening of ghettoes in Lodz, Krakow, and Warsaw. He ensured conditions within them were so bad that hundreds of thousands would die of disease.

Although extermination was not yet official Reich policy, Heydrich knew what his superiors really wanted to do. And, alongside his old buddy Himmler, he set out to ensure it would happen.

In May, 1941, Heydrich issued an order forbidding Jews to leave the Reich, claiming a “final solution” was being prepared.

On July 31 that year, Nazi high command gave Heydrich its blessing to devise a workable plan for this “final solution.”

It was from these black and twisted roots that the poison fruit of the Holocaust was born.

Now, many people were implicit in the Holocaust – not least Heydrich’s BFF Himmler – and we wouldn’t want to let them off the hook by making it appear like it was Heydrich’s work alone.

That being said, the Blond Beast was intimately involved in planning the 20th Century’s worst genocide.

On January 20, 1942, Heydrich summoned leading Nazis to the Berlin suburb of Wannsee for a conference.

Over a three course lunch, Heydrich led a genial discussion on his plans to rid Europe of its Jews.

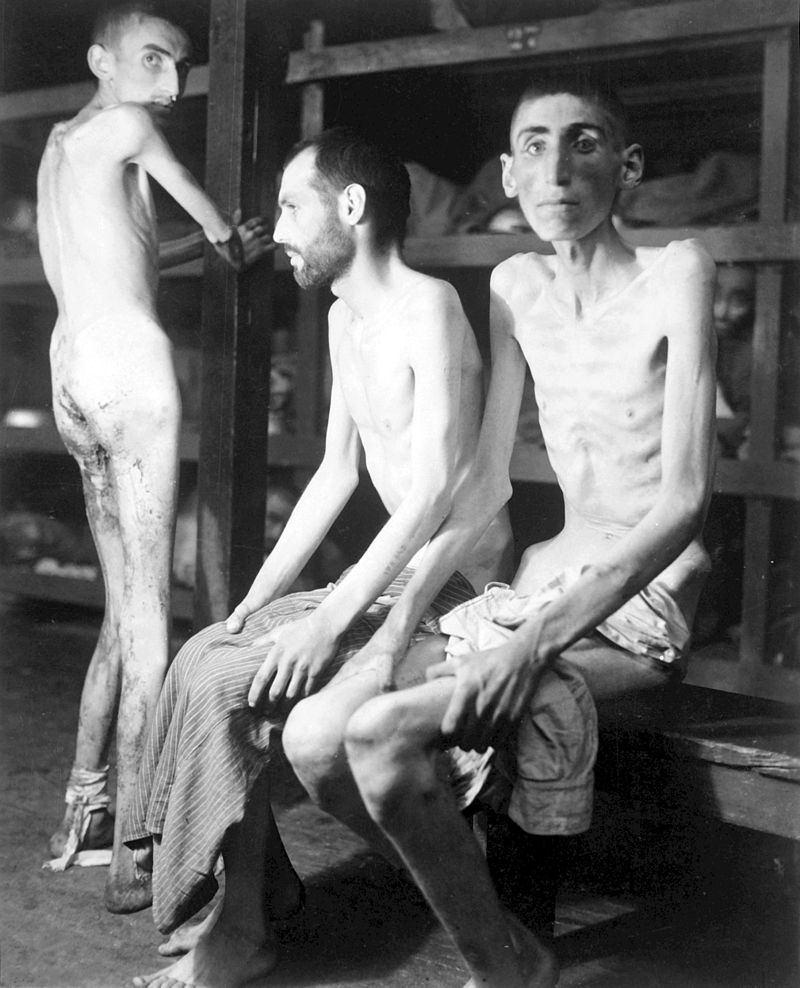

His idea was to march all 11 million east, letting them die through starvation and exposure along the way. The survivors would then be interred in labor camps and worked to death, with any that persistently survived finally exterminated by hand.

When the Wannsee Conference disbanded, the fate of the Reich’s Jews had been sealed. The Holocaust was now official Nazi policy, and it’s chief architect was determined to get started as soon as possible.

But Heydrich wasn’t going to live to see his murderous idea made flesh.

Vengeance was about to come from a very unlikely source.

The “Vermin”

Reinhard Heydrich wasn’t aware of it as he stepped out into the cold Berlin air after the Wannsee Conference, but, far away, two men were already plotting his murder.

Their names were Jan Kubiš, and Jozef Gabčík. They were former Czechoslovak citizens who’d escaped abroad and been trained by British Intelligence.

And they were going to kill the Blond Beast.

The wheels of fate that would set Heydrich, Kubiš, and Gabčík on a collision course had first begun turning nearly three and a half years earlier.

In early October, 1938, the governments of France and Britain had agreed to the German annexation of Czechoslovakia’s Sudetenland region.

Of course, this soon turned out to be a case of “give a Nazi an inch, and they’ll take your entire country,” and five months later, German troops invaded Czechoslovakia.

In Slovakia, a Nazi puppet regime was installed, while the area of modern-day Czech Republic became the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, under direct German rule.

The German invasion of Czechoslovakia wasn’t as brutal as later invasions, like those of Poland and the USSR.

Czech industry was considered too vital to the German war effort to risk disrupting, so the Nazi mass executions of the period usually involved dozens, rather than hundreds or thousands of victims.

In fact, the Nazis were so comparatively soft touch in the Protectorate that a healthy resistance movement sprang up, engaging in frequent acts of sabotage.

It was this sabotage that brought Heydrich onto the scene.

On September 24, 1941, Hitler sacked the former Protector of Bohemia and Moravia in a fit of pique at all these insolent Czechs playing Švejk to his glorious Reich.

In place of the old guy, Heydrich was called in to whip Prague into shape.

Heydrich was not a fan of Czechs. Prior to his posting, he’d referred to his new subjects as “the Czech vermin”. On arriving in Prague, he arranged to have 142 people hanged in just five days.

It was a mission statement. A promise of the blood that would flow through the cobbled streets of Prague if the Czechs didn’t start playing nice.

It was also Heydrich’s own death warrant.

In London, the Czechoslovak government in exile watched Heydrich take his new posting with a feeling of impotence.

Already, the exiled Czechs and Slovaks were unpopular among their British hosts for their apparent unwillingness to take hard action.

While Polish pilots were shooting down German bombers and the French Resistance was engaging in life or death escapades, the Czechs were seemingly content to just sabotage a few factories.

The exiled government needed a piece of concrete heroism they could show the world, to prove they weren’t the weak partners in the fight against Nazi rule.

In Heydrich, they found the perfect cause.

On October 3, 1941, the exiled Czechoslovak government informed Britain’s Special Operations Executive that they were going to assassinate Heydrich. The Brits were all like “you guys are actually gonna do something? Great, let’s kill a Nazi!”

Less than a month later, Slovak warrant officer Jozef Gabčík was chosen for the special mission. He was initially joined by Czech soldier Karel Svoboda, but Svoboda injured himself and was replaced by Czech Staff Sargant Jan Kubiš.

Two months later, just after Christmas, Kubiš and Gabčík parachuted alongside several Czechoslovak commandos into the wintery landscape outside Prague under the cover of night.

As the men moved silently through the snow towards the distant glow of the ancient city, the citizens of Bohemia slept soundly in their beds.

No-one could have known what a firestorm was about to be unleashed.

“Resembling a human”

The name chosen for the plan to assassinate Heydrich was Operation Anthropoid, a word which means “resembling a human.”

It was the perfect name for a plan to assassinate the most inhuman human of all.

Back in Prague, Heydrich had spent his few short months as Protector pacifying first the city, then the country.

The capital had seen the promised bloodshed, with some 400 civilians sent to the gallows. In the wider Protectorate, around 5,000 had been imprisoned and tortured.

But Heydrich hadn’t just gone in guns blazing and noose swinging. It was widely accepted that treating the Czechs like the Poles would hamper the German war effort.

So he’d deployed kindness, too.

Under Heydrich, rations had been increased. Wages raised. Pensions subsidized.

It was a cynical move straight out the far right playbook: stuff gold down the population’s throats to distract them from your crimes.

It had also worked.

As spring, 1942 rolled into view, Heydrich was able to report the Czechs were pacified.

His carrot and machinegun tactics had seen sabotage rates plummet. Factory productivity was booming.

Nazi occupation seemed so accepted that Heydrich even felt comfortable motoring around Prague in an open topped car, with only a handgun and his armed driver for protection.

But Prague wasn’t quite as pacified as Heydrich thought.

Somewhere in the old alleyways of the city, Kubiš and Gabčík laid low in the house of an unsuspecting family, plotting their next move.

They’d made contact with the Czech Resistance months ago, and were now feeling deeply frustrated.

A plan to assassinate Heydrich on a road near his house had been called off at the last minute. Another plan to kill him on a train had been aborted.

They’d now been in Prague nearly five months, and Heydrich was still alive.

It was at this point that someone suggested killing Heydrich on his morning drive to work.

On Heydrich’s regular route, there was a hairpin corner. Anyone driving around it would have to slow to a near-crawl.

In other words, it was the perfect place to kill someone in an open top car.

On the morning of May 27, 1942, Gabčík and Kubiš waited in a tram stop by the corner.

They were dressed in civilian clothes, but there was nothing innocent about them. Under his coat, Gabčík had a Sten gun, while Kubiš had an anti-tank grenade hidden in a briefcase.

As the city came to life around them, the two men waited for their date with destiny.

Shortly after they arrived, Heydrich’s car came into view. As predicted, the driver slowed for the corner.

Gabčík casually stepped into the street, turned, and opened fire with his submachinegun.

At least, that was the plan.

What really happened was Gabčík’s gun jammed. As he frantically tried to fire the fatal shot, Heydrich’s expression turned from one of surprise to white hot anger.

Ordering his driver to stop, Heydrich grabbed his own gun, and raised it at Gabčík.

The Slovak just had time to see the barrel train on him when the explosion hit.

The second Heydrich’s car had stopped, Kubiš had hurled his briefcase bomb.

He was actually off target. The grenade exploded behind the car, knocking all three men down, but killing no-one.

Heydrich staggered to his feet and opened fire on Kubiš, but blast had stunned him and the bullets went wild. Kubiš grabbed a bicycle and escaped, certain the assassination had failed.

Screaming at his driver to get that bastard!, Heydrich ran after Gabčík, firing at the Slovak’s sprinting form.

They ran one street, two… when something odd happened.

Heydrich, the consummate sportsman, found he couldn’t run. He was out of breath.

After a couple of hundred meters, he collapsed on the ground, raised a hand to his side. It came away sticky with blood.

The briefcase bomb had missed its target, but the shrapnel hadn’t.

As the rear of the car was torn to bits, a lump of jagged metal had been propelled deep inside Heydrich’s body.

The Blond Beast didn’t know it, but he was already dead.

Massacre

In the end, it took Reinhard Heydrich eight whole days to die.

For a while, it actually looked as if he might recover. But then septicemia set in and the cultured young man from Halle passed away on June 4.

The response was immediate.

In Berlin, Hitler demanded the heads of 10,000 Czechs. On June 10, SS units walked into the Czech village of Lidice and fulfilled the Fuhrer’s demand.

All the men and boys of Lidice were shot dead, all the women and girls loaded into trucks and sent to concentration camps.

When it was discovered 11 men were outside the village on business, Nazi agents were sent to track them down and murder them too.

All the pets and animals in the village were rounded up and shot. Finally the buildings were set on fire. The Nazis filmed the whole thing, intending Lidice to be a warning to the world.

In Prague, revenge mass killings were carried out, resulting in 1,300 dead. Another Czech village – Ležáky – was targeted and also destroyed.

It was like the Angel of Death had swept across the land, like Heydrich’s poisonous soul was carrying out one last killing spree before returning to Hell.

Three weeks after the assassination, a Czech collaborator, Karel Čurda, passed on the hiding place of Gabčík and Kubiš to the Gestapo. The two assassins were in the basement of Prague’s Cathedral Church of Sts Cyril and Methodius.

On June 18, 1942, 700 soldiers converged on the church. Gabčík and Kubiš held them off for some hours before committing suicide in the Cathedral crypt. The bullet holes from the firefight can still be seen today.

In the West, the reaction to Heydrich’s assassination was equally swift and decisive.

The image of Lidice in flames spurred the Allies to tear up the Munich Agreement.

Until this moment in 1942, it was still possible that a postwar settlement might allow the Germans to keep the Sudetenland.

With images of Lidice fresh in everyone’s minds, that was no longer an option. It was thanks to this one assassination that Czechoslovakia was able to remain a nation after WWII.

But what about Heydrich?

Heydrich was the only high ranking Nazi to be assassinated in the whole of WWII, a fact that explains our continued fascination with him.

But beyond Operation Anthropoid, Heydrich deserves to be remembered.

He was the man who outlined the blueprint for the Holocaust. The man who controlled the infamous Einsatzgruppen.

It was under his watch that the notorious Polish ghettoes were created. Had he lived longer, it’s undoubtable that he would have committed more atrocities.

Unlike nearly every other leading Nazi, there’s no indication Heydrich was a true believer in the early days. More an opportunist who took a job to please his fiancée and then did that job with bloodthirsty relish.

In many ways, that makes him even scarier than someone like his old buddy Himmler.

We like to think of people as either inherently good or inherently evil, but Heydrich wasn’t inherently anything.

He was just a blank, a hollow man. In another life he probably would have made a boringly average Naval commander.

But Heydrich didn’t live another life. He lived this one, with all its bloodshed.

In the end, perhaps all we can say is that the shy, sensitive boy from Halle was simply the perfect anthropoid. A creature that looked human without ever feeling even the faintest flicker of humanity.

(Ends).

Sources

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Reinhard-Heydrich

http://www.historyplace.com/worldwar2/biographies/heydrich-biography.htm

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/reinhard-heydrich-in-depth

https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/reinhard-heydrich-bio

Operation Anthropoid: https://medium.com/@cameronwatson3/operation-anthropoid-killing-reinhard-heydrich-b8cf401ad3

Operation Anthropoid, last stand: http://www.bbc.com/travel/story/20170831-a-prague-church-that-defied-nazi-rule

Wannsee Conference: https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/article/wannsee-conference-and-the-final-solution

German Revolution (1918-19): https://www.thoughtco.com/a-history-of-the-german-revolution-of-1918-ndash-19-1221345